Andrew the Vihuela-Player

by James Gallant

Daniella the black cat sneaks into the chamber, hides beneath a chair, and waits until Andrew is absorbed in his vihuela, then ascends lightly to the windowsill. She likes being there–his playing sweetens her sleep–but he does not like having her in the room. The contented rattle in her throat disturbs pianissimo. Aware of her presence he will remove her bodily.

Today, though, she is not the disturbance: There is a rapping at the door. He opens to Lady Cobb. “Andrew, Jayne needs your help in the kitchen.”

Lady Cobb’s smile has the slightly ironic edge it has always when Jayne and he are associated in any way. She has never approved her husband’s assigning the two servants adjacent private rooms connected by a door– another demonstration of Sir John’s understanding and generosity, as far as Andrew is concerned.

He follows Lady Cobb down the stairway to the kitchen on the lower level. He wears the same fustian work clothes and heavy shoes of Sir John Cobb’s other male retainers, but his red hair is longer on the sides than theirs, the remains of a fashionable haircut he received before playing for Queen Elizabeth.

Dark-haired Jayne, well-endowed in bosom, thigh, and rump, bends over the hearth pot she stirs. When she turns his way, her cheeks are rosy, her forehead curls matted by steam. She’s all business as she equips him with a wicker basket and knife, and orders him into the kitchen garden to pick lettuce and early raspberries. Her hostility has been palpable since she learned he is to leave the Cobbs. Did she suppose they would live together forever, man and wife for all intents and purposes?

There had been a shower while he was at his practice; the flagstones leading into the garden are wet. After hours of musical abstraction, the garden is a bower of loamy-smelling bliss, and his spine tensed by concentration relaxes as he bends over the chartreuse lettuce and plucks leaves near their gritty bases. The lyrics of the medieval troubadour song he is setting to music are running through his mind:

Absent sun,

Stay beneath the dark sea.

Lest he sail, I be undone.

Drowned star,

If you should leave your watery tomb,

Then what is dear to me is far.

Fair moon,

Cease movement, save my life

Weave a spell, forfend the noon.

Eternity,

Deface the heartless calendar.

Rest in peace, my surety!

Footsteps in the grass beyond the raspberry trellis, and voices: Andrew’s surrogate parent and benefactor Sir John Cobb and (Andrew assumes) Richard Hakluyt, who was to have arrived today from Paris with his fiancée Duglesse Cavendish.

“Spain is selling wool from America more cheaply than we can ours. English dominance in the market will end.”

“What will become of our sheepmen?” Sir John asks.

“I fear the worst.”

“King Philip’s been very quiet since Drake embarrassed him at Cadiz. What do you suppose he’s up to?”

“I have no idea, But the Pope called him a coward for letting Elizabeth and a pirate tweak his nose, and he’s a very proud fellow.”

“Been to our stool room since you arrived, Richard?”

Hakluyt laughs. “No, why do you ask?”

“Harrington’s installed for us one of his new odorless flushing commodes.”

“Well, I look forward to being odorless!”

“So do we all!”

The two men are laughing.

Andrew’s knife slips from his hand and lands in the grass.

“Who goes there?” Sir John calls.

Andrew peers around the edge of the raspberry trellis and smiles at the two older men.

“What are you doing, Andrew?”

“Picking raspberries.”

“I’ll have you know, Richard, that lad is one of the finest instrumentalists in England….Andrew, this is Reverend Hakluyt, the author of Diverse Voyages Touching the Discovery of America.”

“Might I ask why one of the finest instrumentalists in England is picking raspberries?”

“Why are you picking raspberries, Andrew?”

“Jayne told me to.”

Sir John winks at Andrew.

“What instrument does Andrew play?”

“The vihuela.”

“I’d no doubt be impressed no doubt if I knew what a vihuela was.”

“An old Spanish instrument resembling our lute. My father brought us one from Aragon years ago. I once showed it to Andrew when he was a boy and I have never seen it since except in his arms.”

“A born musician.”

“So it seemed. John Dowland arranged for him to play recently for the Queen.”

“But he’s a servant?”

“His parents were servants of ours. They died in a fire here some years ago, and Andrew became our charge. Soon he’ll be going to Denmark as a musician at King Frederick’s court.”

“Really? How did this come about?”

“Frederick and my wife are cousins, you know. He paid us a visit after doing business in Edinburgh earlier this year. When he heard Andrew play he wouldn’t leave until we agreed to part with him.”

“And you did?”

“It was either that or have him stay longer and consume all my best wine!”

“The stories we hear of Danish tippling are true?”

“So it seems.”

“Will I get to hear Andrew perform?”

“This very night.”

A pleasant mid-summer evening. The Cobbs, Hakluyt, and couples from neighboring estates, dine on tables arranged amid flower beds in the walled garden.

Andrew does not ordinarily wait tables, but a scullion is ill, and Lady Cobb has asked him to help out. The meals Andrew takes with other retainers do not include meats except at Christmas and Easter. Never having acquired a taste for them, he finds the stench of flesh in the oven room faintly nauseating. He delivers a plate of roasted blackbirds to the garden, and takes up a position to one side of the diners to await commands.

“You wouldn’t believe the number of fine palazzos being built in Paris,” Hakluyt remarks. “Every Tom, Dick, and Harry must have one, it seems.”

“But how does every Tom, Dick, and Harry afford one?”

“There’s an Italian usurer on every street corner offering loans at some incredible rate of interest.”

Andrew tries to imagine wanting a palazzo.

“I was recently at a house whose larder was bare. The owner had so much money tied up in house payments, he could barely afford to eat.”

“I’m much too fond of my roast beef to fall into that trap!”

“So am I!”

Desserts having been served, Lady Cobb whispers, “Andrew, put on your livery.”

To Andrew’s way of thinking, performing in the nude would be symbolism more apt than the garish livery, but since he’s going into the great world as a performer he may as well get used to looking like a juggler. He dons the red-and-gold striped doublet with pansid slops,* gartered gold Venetian silk hose that ascend to the lower hems of the doublet, and a red slouch hat with a golden feather. Vihuela in hand, hoping not to be seen in this getup by other servants, he makes his way back toward the garden.

Jayne smirks at him as he passes the open doorway to the oven room.

Twilight is deepening. Candles have been lit on the tables in the garden. Andrew seats himself in a corner some distance from the diners to pluck the strings softly as he tunes them.

“Duglesse, is your cousin Thomas still drinking tobacco?”

“He’s never without his pipe since coming from Virginia. I was with him in London last week when a Puritan preacher approached us. He informed Thomas that a person who breathes fire and smoke belongs in the bottomless pit and will soon be going there.”

“I hear that a servant saw smoke coming from Raleigh and thought he was on fire. She poured a bucket of water over his head.”

General laughter.

“This is all very interesting,” Lady Cobb says, “but I believe I heard the enchanting sounds of the vihuela.”

The guests smile at Andrew.

“Isn’t he splendid in his new livery?”

“The raspberry and blackbird man has become a Bird of Paradise!” Hakluyt exclaims.

As Andrew draws his stool nearer the guests, Lady Cobb describes his “wonderful opportunity” in Denmark. He does a bit more fine tuning, plays a series of swift runs, and then composes his thoughts a moment before playing a fantasia from Luis de Milan’s pieces for vihuela, followed by his transcription of a lute gigue by Valentin Bakfark, and then his own lengthy, demanding fantasia.

His playing has engendered awed silence in his audience and altered the ambiance of the gathering. At last a woman murmurs, “I didn’t want that to end.”

“I feel I have been to heaven and back,” says another.

The guests rise from their seats, stroll pensively in the moonlit pathways of the garden, or, wanting to be alone with their thoughts, make their way to their quarters in the castle for the night.

Andrew is on the verge of sleep when the door opens tentatively between his room and Jayne’s. He simulates the hoarse breathing of a sleeping person, and the door closes with a bang.

* * *

There is a forest of masts tilting back and forth gently in the harbor at Plymouth Sound. Rowboats large and small ferry passengers and baggage to ships on either side of the stream. Dock workers and carpet bag-toting sailors swarm among oxen and drays, kegs of gunpowder, tall piled coils of thick hemp rope, cannon ball pyramids, tar tubs, barrels of salt beef and salt pork and beer. The sounds of vendors ringing hand bells to advertise their wares reach the cliff above the harbor where Sir John Cobb and Lady Cobb stand with Captain Smathers of the ship Wanderer.

“What an amazing sight!” Sir John exclaims. “How long has the Royal Navy been in port?”

“All month, locals tell me,” Smathers replies.

“A confrontation with the Spanish must be imminent.”

“That’s possible,” Smathers agrees. “The sun and moon were bloody over Plymouth three times this past week.”

“You’ve no doubt heard the Pope declared Philip King of England?”

Smathers laughs. “No, I hadn’t.”

“That would make you and I Spanish subjects.”

“Best of luck to the Pope and King Philip!”

Smathers points a finger. “See those the two men examining demi-cannons? Lord Admiral Howard and Francis Drake.”

“I shall remember this sight as long as I live.”

“It’s been wonderful seeing you again Peter,” Lady Cobb remarks. “How soon will your ship depart?”

“As soon as they’ve loaded the Cornwall tin–within the hour.”

Lady Cobb touches her husband’s arm. “John, we should say our farewells to Andrew

“Indeed.”

The three make their way down stone steps connecting the cliff to the harbor.

The sea chest Lady Cobb has had prepared for Andrew’s voyage to Denmark consumes most of the floor space of his small cabin. Andrew assumes he will be asked to perform soon after arriving at Elsinore, so it will be important to stay in practice while en route. But he cannot seat himself properly to play with the chest consuming floor space. Once the ship is underway he will ask Captain Smathers if the chest might be relocated. Meanwhile, seated in his bunk, he studies in the dim light cast by a spirit-lamp his transcription for vihuela of John Dowland’s lute piece, “Fancy #3.” He can hear the piece in his mind’s-ear as he makes small changes in it.

The little bells dinging somewhere nearby are a distraction. He wishes they would stop.

With the sea chest in the middle of the floor there is room enough only for Lady Cobb. Sir John remains in the open doorway.

Lady Cobb extracts from the sea chest a bottle and says to Andrew, “This contains cider. You will find it very refreshing after the salted meat served aboard ship.”

The pervasive melancholy cast of Dowland’s music might be explained, Andrew supposes, by the fact that he has never found preferment at the English court. On the other hand, temperamental melancholy might explain his never having found preferment, since, as Andrew knows from personal experience, Elizabeth favors lively gigues and saltarellos.

“Before biting into a sea- biscuit,” Lady Cobb advises, “examine it to see if rodents have been there before you.”

“You may lose a tooth biting into one,” Sir John adds.

Lady Cobb removes from the chest a small rectangular metal container open on one end. She holds it up for Andrew to see. “If you place this little oven near a fire, it will soften your biscuits.”

“Where is he going to find a fire aboard ship?” Sir John asks.

Andrew is proud of his transcription of “Fancy No. 3,” although to play it well will require a great deal of practice. He should probably exclude it from his performance repertoire for the time being.

Lady Cobb extracts a jar from the chest. “You can also use the oven to heat this soup Jayne has prepared for you.”

Andrew wonders if it poisoned.

The Wanderer makes its way out of Plymouth Sound into the English Channel and sets a course for the North Sea. Captain Smathers is at the window of his cabin in the poop deck, hands clasped behind his back, when he sees something that makes him reach for his spyglass: a multitude of ships’ masts frail as toothpicks coming up over the southwestern horizon.

As a favor to his friends the Cobbs the Captain invites his young passenger to dine with him that evening. As they sit at the captain’s table awaiting the cook’s delivery of their meal, Andrew is reflecting on the inferiority of Dowland’s polyphonic works for vocal consorts to his lute solos. The trouble with words is that they come into music bearing the dross of the human ordinary; they lack the enchanting otherness of sounds generated by sheep guts and wood.

Smathers has been contemplating the absent expression on the young man’s face when he breaks the silence: “I think we may have narrowly avoided an encounter with the Spanish Armada this afternoon. We would no doubt have heard cannon fire, had there been a battle. But one can only wonder what the morrow will bring.”

Andrew has no idea what the Captain is talking about.

“Hard to say what the outcome would be. The light swift carracks of the English are superior to Spanish galleons from the standpoint of maneuverability.”

Smathers’ eyes narrow at the young man’s smile which seems a curious response to his remarks. (Andrew has heard him to say that the English have “light, swift carrots.”)

“On the other hand,” Smathers continues, “the Spanish have a great many galleons. They might lose a number of them without losing a battle to the carrots.”

Smathers has gathered from the Cobbs that their young man is exceptional in some respect, but his smile is that of an idiot. Smathers’ extensive experience of idiocy over the years while managing crews has sensitized him to its symptoms, and generated a theoretical interest in the subject. He has gathered from his reading a little nosegay of quotations on the subject. Erasmus in Praise of Folly alludes to Pythagoras who after many transmigrations–his soul had been embodied at one time or another in “a philosopher, a man, a woman, a fish, a horse, a frog, and, I believe, a sponge”— concluded no creature was happier than “that type of men we commonly call fools, idiots, lack-wits, and dolts.”

The cook enters the cabin and places before the two men plates of salt beef and suet pudding. The Captain digs in. His passenger nudges the beef to one side of the plate with his fork, downs a spoonful of the pudding, and winces.

Smathers honors Andrew’s request to relocate the sea chest. A music stand now occupies the middle of the cabin floor. Andrew, seated before it struggling with the devilishly difficult left hand fingering in his transcription of “Fancy No. 3.” is thinking, “I have brought this on myself”–when the North Sea generates one of its sudden howling squalls. The ship begins to heave dramatically, its timbers creak. Andrew is aware of the disturbance, but he has trained himself to ignore the distractions that abound in the world and perseveres. By the time the ship’s jostling ceases, he has mastered, for the time being, the fingering for “Fancy #3.” Savoring the pleasurable aftermath of self- and world-overcoming, he ventures from his cabin up to the deck.

The sun on the Western horizon is a luminous orange perched on the edge of a grey table. The crew are firing blunderbusses into the air, celebrating an escape from pirates who had been gaining fast on the Wanderer before the storm overturned their hoy.

Captain Smathers, aloof from the hilarity on deck, greets Andrew, and informs him that the ship lies off Schiermonnikoog.

“Ah,” Andrew says.

“Schier is grey–the island of the grey monks. A storm once drove me aground onto Schiermonnikoog. I stayed for a time with the Cistercians. They wear grey habits.”

“Hmph.”

The Cistercians had struck Smathers as idiots.

* * *

Ordinarily, musicians and painters at Kronborg Castle, Elsinore, eat simple fare from bread trenchers with other servants. Today, though, at Queen Sophie’s Arts Appreciation Banquet they dine on pastries filled with beef marrow, roasted swan and cranes and pheasant, eels in a puree, and bream. The wine is flowing.

Andrew’s life at Elsinore has been strangely uneventful so far. He had assumed he would be asked to perform soon after arriving, but a month has passed, and nothing has been asked of him. He has enjoyed ample free time in which to maintain his skills as a player, and to work on his compositions, but he has felt at times like a ghost haunting the castle. Is the King even aware of his presence? When Andrew had mentioned his not having once seen Frederick to the English pastry cook whose arrival in Denmark had been almost simultaneous with his, the cook replied that the King had sought him out three times to request specific pies.

“You eat like a bird, Andrew,” remarks Lady Gyldenstjerne at his side. Gyldenstjerne, drama coach and arts coordinator at Kronborg, is a tall, big-boned Dane with wide-set eyes. She devours birds with gusto.

Axel Bente, the music-master, seated on Andrew’s other side, says, “The Scottish ambassador told me the North Sea winds did more damage to the Spanish Armada than the English warships. Protestant winds, he called them.”

“King Frederick’s sensitivity to music must be very great,” Andrew remarks.

Bente cocks an eyebrow. “What gave you that impression?”

“When I played Dowland’s Lachrimae for him in England, he wept.”

“Was this late at night?”

Andrew nods.

“I assume he was in his cups?”

Frederick, when his eyes filled with tears, had been gazing at Andrew over the rim of a tall flagon.

“Not to disparage your considerable talent, Andrew, but if Frederick’s had his nightly quota nearly anything will make him blubber.”

“I understood he was to be at the banquet today.”

“He’s in negotiations with the Scottish ambassador. By the way, they want you to perform with the Elsinore Town Band on Hven next weekend.” Bente’s grimace expresses personal abhorrence of this obligation.

Andrew wonders who “they” are.

“Be at my place in town this afternoon at four to rehearse.”

“The band makes such a merry sound!” Gyldenstjerne gushes.

The English pastry cook wheels into the Great Hall a cart bearing a gigantic Lombard pie* that brings a susurration of wonder from the banqueters.

Bente leans close to Andrew. “See that girl with the straw-colored hair by the Queen? That’s Princess Anne. She’s been making eyes at you. I’d not respond to that overture, if I were you. Frederick’s trying to marry her off to James the Sixth of Scotland.”

“She doesn’t look much like a queen,” Andrew observes.

“What woman does before the makeup artists and dress-designers go to work? I mean, strip your Queen Elizabeth of corset, farthingale, and ruff, you’d be looking at a plucked chicken.”

Gyldenstjerne’s eyes roll.

With Lombard pie under their belts, the guests are burping and sighing. The banquet seems to be winding down, and Andrew senses his liberation is at hand when Lady Glydenstjerne offers him her personal guided tour of Kronborg Castle. It does not seem politic to decline her offer, so he follows the rustling skirts that overlay her substantial posterior along a narrow corridor out into the deeply shadowed central courtyard of Kronborg Castle where she discourses on the significance of the Neptune Fountain, and the sculpted figures of Moses, Solomon, and David (Frederick’s predecessors in the administration of Justice) in niches by the Royal Chapel entrance.

“You’re going to love the royal tapestries,” she says as they enter the Hall of Knights. “They portray the kings of Denmark from the beginning to the present.”

The tapestries remind Andrew of Boethius’s remark that in things that do not move there is no music.

“Axel said the town band is to play at Hven. What is Hven?”

The question stops Gyldenstjerne in her tracks. Judging from her look, his question has betrayed abysmal ignorance.

“Why, Hven is Tycho Brahe’s island where he will entertain the royal family and the nobles this weekend.”

Andrew does not think it wise to inquire who Tycho Brahe might be, but Gyldenstjerne seems to have guessed his ignorance: “Mr. Brahe is the first man to have observed a new star in the heavens.”

“Ah.”

“It proved that the superlunary heavens are not immutable, as commonly supposed. And his observations have confirmed Copernicus’s belief that the planets rotate around the sun. Of course, he is not of those who believe the earth does.” Glydenstjerne shakes her head at the preposterousness of such a notion.

It escapes Andrew why people would want to know which heavenly bodies circle which. Do they imagine clarity in the matter would enable control of these movements? If not, what difference can it possibly make?

Escaped at last from Gyldenstjerne, he is in his private quarters embracing the vihuela, which warms to his touch, when someone knocks at the door. Vihuela in hand, he opens to a page who hands him a copy of Emil Fritjok’s Latin Life of Tycho Brahe, “with Lady Gyldenstjerne’s compliments.” The vihuela pops a gut that flies from the soundboard and lashes the hand of the astonished page. Andrew thanks the page, shuts the door, throws the book in a corner, ties a new string on the vihuela, and enjoys two hours of blessed communion with his music before he must go to town.

When he opens his door to leave for the rehearsal of the Elsinore Town Band, girly-gangly Princess Anne, her straw-colored hair in a bouffant, is in the corridor. “That was so lovely! What is your instrument?”

He tells her. She places a hand on his arm and looks up at him pleadingly: “Teach me to play!”

Axel Bente’s flat in Elsinore is above the fishmonger’s shop.

Bente leads Andrew to the back of the apartment into a staircase with a window overlooking Elsinore backyards: board fences in various states of repair, chickens picking at grain, a goose, a pig pen, a mulch pile, an overturned driftwood-grey wheelbarrow with its wheels in the air.

Members of the Elsinore Town Band sit on short logs set upright in the yard. A cornetist toots, a crumhorn whines, a sackbut blares flatulently, a tabor-player drums a taut skin. Three neighborhood mongrels side-by-side on their haunches, throats elevated, howl supportively.

Bente shoos the dogs, and introduces Andrew to the band.

“I don’t know how to tell you guys this, but Brahe’s wife wants us to dress as animals when we perform on Hven.”

Groans.

“Good ol’ Kirsten!”

“People laugh at her,” Jaeger the cornettist says, “but if you ask me that’s one fine piece of ass.”

“Yeah, and the beauty is,” Hans adds, “there’s enough of it to go around.”

Bente opens a chest which stands along the back wall of the house. “Question is, can we perform in these getups?” He extracts a furry one piece costume. “Hans–bear?”

“Why not?”

“Obviously our cornettist should be the cock–Jaeger?”

“Better cock than cuckold,” said Jaeger. He inserts the mouthpiece of his instrument through the short beak, and sounds a cockle-doodle-dooooooo.

A window nearby slams shut.

“Peder–you be the wolf….Skraeder, cod?”

“I’ve always felt a bit supernatural.”

“Cod,” Bente says, “fish.”

Andrew dons the raven’s head.

“Who but an ass would lead this group?” Bente says, pulling a papier-mâché donkey head over his. He brays hollowly from within. “First Up, ‘Rufty Tufty.’” He raises a director’s hand, and sets the band in motion.

Andrew has no idea what he’s supposed to be doing, but strums a rhythmic background. The donkey gives him thumbs up. The string Andrew had just tied on the vihuela breaks. He continues strumming with it flying about.

* * *

Below looming, grey, Kronborg Castle with its high walls and onion-minarets, parallel rows of spear-bearing guards form a corridor reaching from a pier to the gangplank of a barge docked in the Oresund.

The royal bloodhounds and riding horses, and their keepers, and the members of the Elsinore Town Band, await boarding for the short trip to Hven. The summer sun is intense. Andrew shares the shade of an umbrella with Axel Bente who is ruminating on the political implications of the just-signed marriage contract that will unite Princess Anne with King James of Scotland: “James is the son of Mary Queen of Scots, and grandson of Henry VIII, so he’s heir-apparent to the English throne. He marries a Protestant princess– that reassures Elizabeth he hasn’t the Catholic leanings of his mother. For Frederick, the marriage settles the longstanding issue over ownership of the Shetlands and the Orkneys– and it makes the rascally Princess someone else’s problem.”

Andrew nods as if he were following this line of reasoning, and remains silent for a time so as not to change the subject too suddenly. “You know, I haven’t once been asked to perform solo since I arrived in Denmark. I’m wondering why Frederick wanted me to come here.”

Bente looks at him blankly for a moment as he adjusts to the change of subject. “Frederick collects virtuosos—not that he gives a rat’s ass about music–or astronomy or philosophy. He wants people to regard Elsinore as the northern Florence.”

Eight heralds in purple tights, white tunics, and caps with big plumes dyed violet descend the walk to the pier, halt, level their horns, and sound a brassy tarum-tarum-tarahhhhhhhhh.

“You’ll find the Danes are very big on fanfares,” Bente says. “It’s all Frederick can do to get one of his sluts through the back door of the castle without those boys tooting.”

The King and Queen, accompanied by Princess Anne, the boy Prince Christian, and servants, descend the walk to the pier. Frederick’s long, ruddy, deeply- lined face floats atop a large white ruff. His bloodshot eyes meet Andrew’s briefly, without recognition. Following the royal family are an assortment of Danish nobles and the Scottish ambassador George Keith, a red-haired, freckled-faced, buck-toothed fellow with a permanent smile. Princess Anne breaks through the corridor of castle guards to brush against Andrew and whisper, “When do my lessons begin?”

Bente gives Andrew a look.

The King and Queen seat themselves beneath a canopy in the barge. A pair of servants begin waving long-handled fans. A third hands the king a tankard. The gangplank is drawn up, and deckhands equipped with long poles shunt the boat into the stream. Oxen tow to the edge of the pier a second barge which the royal hounds and horses, their keepers, and members of the Elsinore Town Band board.

“What’s this about lessons for the Princess?” Bente asks.

Andrew shrugs. “Her idea, not mine.”

“Be careful, Andrew.”

The voyage to Hven is brief. As the royal barges approach the island, peasants on shore toss their hats in the air and make loud huzza-huzza. Barrel-chested, sandy-haired Tycho Brahe, with the dwarf Jepp at his side, greets his guests in front of his red brick castle Uraniborg* with its peaked roofs, dome, and balconies.

“Hello, dear little Jepp,” Queen Sophie says.

Jepp gives her the finger.

Brahe leads his guests to the entrance of his observatory Stjärneborg and pauses to let them savor the inscription in gold letters on porphyry:

`Consecrated to the all-good great God and Posterity. Tycho Brahe, Son of Otto, who realized that Astronomy, the oldest and most distinguished of all sciences, though studied at length, still had not obtained sufficient firmness, or been purified of errors, and in order to reform it and raise it to perfection invented with incredible labor, industry, and expenditure exact instruments suitable for all kinds of observations of the celestial bodies.

“I can only imagine it must have been like to observe the birth of a star,” says the admiring Lord Kaas.

“Yes, I perceived its implications for affairs in Russia, Finland, Sweden, and Norway,” Brahe acknowledges. “I informed King Frederick of these and he rewarded me with the professorship of astronomy at Copenhagen.”

After dinner, the Elsinore Town Band performs “Begone, Begone my Jug,” and “Haloo, Fair Birdie,” and there is a skit in which Tycho Brahe’s sister plays Urania, muse of astronomy. Brahe shouldering lightly a large globe impersonates the Titan Atlas who declaims, “It is I who have taught astronomers from the time of Hercules and Hipparchus to trust not other men’s observations of the night skies, but attend to them patiently with their own eyes, using well-constructed instruments.”

In a second skit, Princess Anne dressed in green tights portrays Daphne. Apollo is the Negro son of a cook and a wardrobe manager at Kronborg. He wears golden tights and a spiky gold sun mask as he chases Daphne around a screen depicting a leafy rural scene.

“Save me Mother Earth!” Daphne cries.

“Tarry,” Apollo pleads. “I am no lion or a tiger, I am Phoebus Apollo. I hunger only for thy lips.”

“Which pair?” Daphne ad-libs over her shoulder, cracking up the sun god who trips over the edge of the screen and falls to the floor.

Skit director Lady Gyldenstjerne closes her eyes.

Princess Anne plants a foot on the back of the fallen god and addresses the audience. “The moral is, if you can make a god laugh, he might not fuck with you.”

The Danish nobility are in stitches.

Queen Sophie stares at the ceiling.

Scottish ambassador Keith is reconsidering the marriage agreement he just signed on King James’ behalf.

The dormitory on the second floor of the castle sleeps the dog-trainers, the grooms, and the Elsinore Town Band. The day’s heat lingers there. Andrew finds sleep impossible in the large assemblage of snorers, and rises from his pallet toward midnight to look out a window into the labyrinth below. At its center is a white marble bench bathed in moonlight. Sitting there and playing something simple and sweet on the vihuela would be pleasant, he thinks. He dresses again, picks up his vihuela, and leaves the castle.

High walls of shrubs border the paths of the labyrinth. Reaching the center proves more challenging than he imagined. At dead ends he must retrace his steps, and while doing so he hears footsteps nearby. Someone else is in the labyrinth. When he finally reaches the center, he starts at the sight of Princess Anne seated on the marble bench. She wears white tights beneath a white tunic, and has her knees drawn up to her chest. A pair of lean hounds at her feet growl at the sight of Andrew. Anne drops her feet to the ground and sits upright. Pleasure and apprehension blend in her face. “Did you follow me here?”

Andrew, torn between a desire to backtrack into the labyrinth and the absurdity of doing so, holds up the vihuela in explanation of his presence.

“You’re going to give me a lesson?” The Princess slides to one side of the bench to make room for him.

Andrew hesitates, wondering who might be viewing what is ostensibly a tête-à-tête from one of Uraniborg’s many windows, but he approaches the bench. He seats himself a comfortable distance from the Princess, and lays the vihuela across his lap. She reaches over and runs an exploratory finger across the strings. “Such a beautiful instrument.”

“I understand you’re to be queen of Scotland.”

“So they tell me. It keeps me awake at night.”

“You’re too excited to sleep?”

“Too depressed.

“You don’t want to be the Queen of Scotland?”

“Would you?”

“Many women would leap at the opportunity.”

“Even if they had to marry James Stuart?”

“What’s wrong with James Stuart?”

“Well, he’s skinny, and bow-legged. They say he wears padded clothing to bed at night–he’s scared of being stabbed.”

“That might be a good idea, in Scotland.”

“He also plays the bagpipes.”

That might be a reason not to want to marry him, Andrew thinks.

“They say when he concentrates, his tongue falls from his mouth.”

“I sometimes drool if I’m very intent on what I’m playing,” Andrew confesses.

“You needn’t have told me that. My father wanted James to marry my sister Elizabeth. She’s prettier than me, but she’s getting kind of old. He probably wants young tail.”

“You’ve met James?”

“No–and he isn’t coming for the wedding.”

“Really?”

“The Scottish ambassador will be the proxy husband. It’s all just politics. You know what? This afternoon I overheard one of the grooms calling me a dog.”

“Off with his head.”

“But it’s true, I’m not beautiful. What’s the good of being a princess if you aren’t beautiful?”

“I would think being a princess would be especially valuable if you weren’t.”

“You agree with the groom, then?”

“I didn’t say that.”

“Would you like to fuck me?”

Andrew strums a descending chord progression on the vihuela.

“Are you a spy?”

“Why do you ask?”

“Wouldn’t put it past ‘ol James to put one on me–and you’re English.”

“It’s not the same as being Scottish.”

“Lucky you.”

“I’m no spy.”

“James sent me a girdle of Venus.”

“What’s a girdle of Venus?”

She pulls the neck of her blouse aside to reveal a blue pearl-studded wrap about her chest. “I’m to wear it until he takes it off personally. Isn’t that special?”

Andrew plays a bit of Gaucelm Faidit’s longing-saturated troubadour melody from the twelfth century.

“That’s so lovely. Teach me to play that thing. Please?”

“Here? Now?”

“Yes.”

“It’s not like teaching a dog a trick, you know.”

She punches him on the bicep.

An unfortunate choice of words.

Andrew is walking along a corridor of Kronborg Castle from the music studio to his private quarters one day when Princess Anne appears out of nowhere, seizes his hand and draws him through a doorway into a steep, spiraling staircase leading down into the bowels of the castle.

“Bet you haven’t seen our dungeon.”

“I didn’t know there was one.”

“Silly! Every castle has a dungeon!”

A guard or two has accompanied Anne ever time he’s seen her lately. “Won’t they miss you upstairs?”

“Who cares?”

She leads him to the foot of the stairwell, and along dirt paths cut between earthen banks.

The main feature of the he torture chamber is a freestanding stone pillar with inlaid iron rings. “They hang a prisoner from the rings, and poke him with hot irons, or shoot arrows into him,” Anne explains. “Can you imagine?”

Andrew can.

The dungeon is a cell with rocks walls whose width and height diminish at its far end.

“No bars,” Andrew observes.

“They install them when there’s a prisoner. They can locate them all the way to the back so a person can’t even sit down.” She demonstrates, wedging herself into the acute angle where the walls meet. She simulates helplessness, and a blast of sexual radiation from her midriff causes him to start back to the stairs. He has only just returned above when a squabble in the corridor causes him to look over his shoulder. Two tall castle guards, each with a meaty hand under one of the Princess’s elbows, are carrying her off. Her feet are off the ground, thrashing about.

Gertrud’s Tavern in Elsinore has become Andrew’s refuge from Kronborg Castle. He would never try to compose music there, but the noisy tavern has the paradoxical effect of heightening concentration as he is editing his compositions. When he enters this afternoon with his vihuela bag on his shoulder, the tavern is unusually quiet. The barmaid Agnete greets him: “Hi Cutie.”

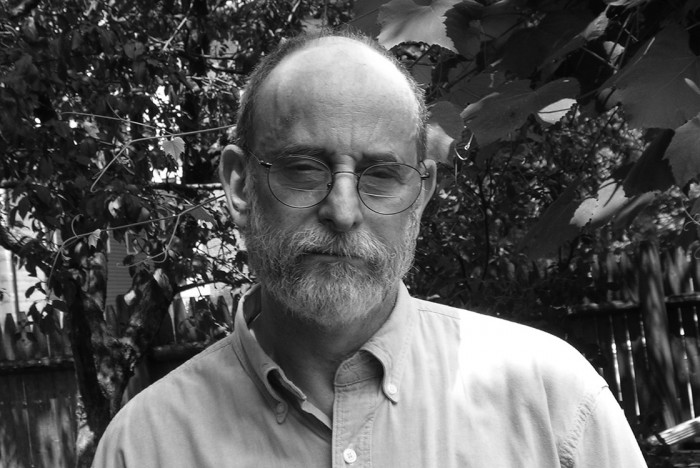

On his way to the back room, he passes seated at a small table the balding Englishman often at the tavern lately. Andrew had been told that he is a member of the English theater company performing repertory in Elsinore.

Today, the Englishman bends over the text of his play that will receive its premier performance at the Elsinore Town Hall next week. The play set in Elsinore has a story drawn from Danish history. It should have immediate local appeal, but something about it is elusive for the playwright. Staging Hamlet in Denmark will hopefully improve his understanding of what he has written, and perhaps inspire revision, before he plays it to the more discriminating audiences of London.

William Bull, a stocky, red-faced bit-actor in the English company, storms into Gertrud’s looking for Tom Boltrum, another actor. Bull is enamored of Abigail, the pretty young widow of Elsinore who has just told him to leave her house and never return. Bull thinks he knows why, and he’s going to have it out with Boltrum, who is usually at the tavern when he’s not working. He is absent at the moment, so Bull seats himself near the entrance to wait for him.

Gertrud and Agnete are in the tavern’s side yard roasting meats for the dinner crowd when Boltrum enters.

“OK, why’d you do that?” Bull says.

“Why’d I do what?”

“You told Abigail what I told you in confidence.”

“What you told me in confidence was she loved no one but you. When I told her that, she couldn’t stop laughing.”

“Leave her alone, you whoreson codpiece! She’s a nice girl–and as it is you’re screwin’ every woman in Elsinore under age ninety.”

“I’ve left you a spongy old malkin or two.”

Agnete reenters the tavern as Bull punches Boltrum. Boltrum punches Bull in the nose, knocking him to the floor. Bull picks himself up slowly, bleeding from the mouth, gives Boltrum a hostile look over his shoulder, and exits the tavern.

Boltrum seats himself at the bar, and Agnete places a bowl of ale in front of him. “What was that all about?” Tom’s head is aching, he doesn’t want to talk about it, so Agnete goes into the kitchen to wash dishes.

Andrew, in the back room revising of his new work, “Princess Anne’s Gigue,” had been unaware of the struggle out front. So, too, the playwright, his attention riveted by the inadequacies of Hamlet’s soliloquy in act three, scene one:

Here’s a thought: Suppose I kill myself?

Ye gods, the problems! And who can say for sure

Whacking away at them with a bare bodkin’s

Nobler than just stabbing oneself in the gut?

Slough the mortal coil! Eternal slumber!

That might be a way to go–although

Sawing it off, we tend to dream, and what

If nightmares dog the suicide?

The last line of the soliloquy–“Conscience doth make cowards of us all”—isn’t bad. The rest of it needs work, but the playwright’s creative energies are at low ebb and time for the actors to learn new lines is growing short. He is considering getting drunk and forgetting about the soliloquy when there appears before his imagination a chart of the celestial houses spinning like a top from which a voice issues: “To be or not to be. That is the question”–a superb replacement for the clumsy first line of the soliloquy. The voice continues: “To die: to sleep/ No more, and by a sleep to say we end/ The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks/ That flesh is heir to, ’tis a consummation/ Devoutly to be wish’d.”

The Englishman is writing down lines as fast as they are dictated when Bull comes through the door of the tavern, withdraws a sword from his pant leg, and runs Boltrum through the gut, back to front. The tip of the sword lodges in the front of the bar. Agnete reappears, a dish towel slung over her shoulder, Boltrum is sitting upright on his stool, a carcass on a spit. “Get you another, Tom?” she asks before noticing the lack of animation in his startled face.

She rushes into the side yard. “Oh my god,” Gertrud says, “that’s all we need with the mayor trying to shut us down. Did anyone see it happen?”

“I don’t know.”

As the two women dislodge Boltrum from the bar, Gertrud eyes the Englishman writing feverishly at his table. They manage to get the corpse off the bar stool and into the kitchen. Gertrud opens the door there and glances up and down the alley. They drag Tom Boltrum into a grove of pine trees on the hillock beyond the alley.

When the fit is upon the playwright, lines just keep spilling onto his pages. The slightest event or sensation is assimilable in language Odors of roasting meat are coming into the tavern from the side yard. The playwright scribbles in the margin of his playbook, “Something rotten in the state of Denmark” He will use it somewhere.

A woman’s voice beyond the tavern shrieks, “Poor Tom’s a-cold! Poor Tom’s a-cold!”

The playwright dips his quill in ink.

Preparations for the wedding of King James and Princess Anne are furious at the castle. Dress-designers, carpenters, furniture-makers, and carpet weavers throng the halls. Fabric chandlers push about handcarts loaded with of silks, velvets and brocade. The tailors’ assistants stitching away in corners outnumber spiders.

The musical consort for the royal wedding is to include Andrew on the vihuela, two recorder players, the court lutenist Raphael de Angelo, and Axel Bente on the viola da gamba. The consort is rehearsing one day when an officious little German tailor appears in the music studio with a tape measure around his neck and orders Andrew to stand up.

“Why?”

“I measure you.”

“Measure me for what?”

“Your clothes for the coronation at Edinburgh.”

Axel Bente gives Andrew a look.

Andrew learns that he is the only musician from the court to be so honored.

His new clothes include two doublets with short skirts, flies tied with colorful silken bows; a high-crowned, short-brimmed muffin hat with a feather; shirts with standup collars, lace at the neckline and wrists; a long, fur-lined cape; and a collection of cotton stockings in various colors with leather garters.

He is practicing the vihuela in the music studio one morning when a cannonade thundering from the castle ramparts cause him to peer through a narrow window overlooking the Sound. Ships flying Scottish colors are approaching the pier below the castle where Danish dignitaries have gathered. A fanfare from the Danish royal hornsmen answers one from the deck of a Scottish ship. Horns glint in the sunlight, water shines, cannons boom. The Scots come ashore wearing identical cartwheel linen ruffs at their necks, tall black hats, and pointed beards.

Andrew is present with the Elsinore Town Band at an entertainment for the visiting Scots that includes the performance of the skit “Solomon and Sheba” in which King Frederick plays Solomon. Lady Kass (she of the beguiling décolleté) is Sheba. Solomon has been drinking and requires the aid of servants to ascend the riser steps to his throne chair. Sheba, too, is none to steady on her feet, and as she presents the riddles to test Solomon’s wits her speech is slurred. Solomon’s responses, slow in coming, require prompting from Lady Glydenstjerne, but suffice to convince Sheba that the king is indeed God’s elect. She wishes to present personally one of the many gifts her servants have lugged from Arabia in a mule train: a bowl of honey-laced date pudding. She ascends the steps to the throne very carefully with it and has reached the next-to-last step successfully when she trips, spilling pudding and bosom into Solomon’s lap.

“Oh my God, the goo!” exclaims the laughing Solomon as he fondles the slimy Sheba.

Servants come rushing with mops and towels.

The Elsinore Town Band strikes up “Hark, the Dog is in the Pork.”

* * *

At the wedding rehearsal, Anne’s lady-in-waiting slips into Andrew’s hand a poem King James has sent the Princess on which she has scribbled a marginal note: “God, he’s a maniac!”

TO MY QUEEN

Whenever I’m oppressed with heavy heart,

I need but take my pen, and recollect

The blessed hour when first my eyes beheld

The image of my Queen, this earthly Juno.

Three Goddesses of equal reputation

Spied the beauty, and nearly came to blows

O’er who should rule her. They Apollo

Asked, who said, “Bless this paragon

By sharing her; and so it came to be

If counsel’s what I need, Athena’s nie;

Chaste Diana mounts to hunt with me;

And if I’m tired, and would to bed repair

I fold in soft embrace my Venus fair.

In the Royal Chapel, the Princess exchanges vows with the freckle-faced, permanently smiling, proxy husband ambassador George Keith. Andrew is with the musical ensemble in the choir loft, and from his vantage, Anne in the white, hooded dress that flows around her and spills onto the floor seems quite overwhelmed by the weight of ceremony and authority– not at all herself.

* * *

The flotilla of Danish and Scottish ships leave Elsinore and steer northward in mild early fall weather. George Keith, the proxy husband, his stiletto beard flapping in the breeze, follows Anne around on the Gideon like a faithful dog. Anne shoots exasperated looks across the deck at Andrew.

Anne’s lady-in-waiting hands Andrew another of King James’s literary efforts with another of Anne’s notes: “I’m married to a lunatic!”

TO MY QUEEN

The wings of your enchanting fame have reached

Me across the wide and stormy sea.

Your smile will be my antidote against

The melancholy that oppresseth me,

And when a raging wrath within me reigns

Loving looks from you will bring me peace.

Whenever you will see me heavy-hearted

Practice then, sweet doctor, your magic art.

Andrew notices Keith gazing at him with squinty eyes.

Winds intensity as the ships enter the Skagerrak. Great waves begin to roll the Gideon from side to side and up and down. From peaks there are dizzying panoramas of churning white waters which disappear as the ship’s prow drops into dark troughs. Gray-faced and vomiting, Andrew retreats to his hammock in the forecastle where he embraces the vihuela, hoping to prevent its destruction. The Gideon springs leaks. All through the night the crew man the pumps.

The winds die abruptly at daybreak, and the cobalt sky and silver sun are innocent-looking. Ships that launched with the Gideon are nowhere to be seen. Admiral Munk orders the Gideon steered to a small harbor visible in the distance which turns out to be at Flekkeroe, an island near the Norwegian coast. The Flekkeroean farmers, learning of the ship’s fate, invite the passengers and crew into their homes, but warn that drought and poor fishing have reduced their food supply to subsistence levels.

Admiral Munk, touched by their hospitality and their plight, orders foods brought from the Gideon to be distributed among the cottagers, but discovers while overseeing this operation that the salt beef and pork in the ship’s hold are moldy. Sea biscuits swarm with brown grub worms, and maggots have infested the dried apples. The victualer in Copenhagen he had thought trustworthy, though Catholic, has obviously stocked the ship with leftovers from other voyages. The beer is sound, however, and he orders a barrel of it delivered to each of the homes entertaining the Gideon’s passengers and crew.

The largest log house on the island is Peder Pedersen’s. A note delivered to the house with the barrel of beer informs Mrs. Pedersen that Princess Anne of Denmark and other nobles will be staying with her and her husband. Mrs. Pedersen picks up her broom and sweeps vigorously the dirt floor around the fire burning on a stone slab at the center of the room. She replenishes the lamps with cod-liver oil, sprinkles fresh sprigs of juniper about, and draws the trestle table and benches from the wall.

Princess Anne requests that Andrew the vihuela-player, though a commoner, be lodged at the Pedersen’s, “because I think we will have serious need of entertainment while the ship is being repaired.” George Keith accedes to this request–having Andrew near to hand will facilitate surveillance. However, he assigns the young man to sleep in Pedersen’s barn with members of the Gideon’s crew, rather than in the house.

Mrs. Pedersen, wearing her festive red bunad with its elaborately embroidered high bodice, long pleated skirt, and white apron, places before each of her noble guests at table a quantity of hemp seeds, thick slices of bread, and a bowl of the ship’s beer.

Peder Pedersen bows his head.

“Lord,” he commences, “we thank you for your bread, and your seeds. People ask which came first, the chicken or the egg. What I would like to know is which came first the plant or the seed. I mean, where would chickens be without grains?… While I am on the subject, why do pea vines watch the sun so carefully all day long? Do they not trust what it is going to do next? Lord, these things are beyond our understanding. As the Good Book says, we look through a dirty window. But we thank you that our guests have come safely through the storm and brought us this first-rate beer. Amen.”

George Keith’s perpetual smile is a plaster replica of itself.

The bread’s consistency is chewy. It has a flavor evocative of pine needles. Peder explains that in hard times the residents of Flekkeroe and neighboring Kristiana bake this bread from fir bark ground into meal.

The beer and hemp nuts are popular.

After downing numerous bowls of beer, Peder leaves the room, and returns dragging behind him the ax six feet long with a worm-eaten handle and an oversized blade that he found buried in his hemp field. He speculates that it belonged either to the primeval giants, or the trolls who delight in baffling humans with curious objects planted about the countryside.

For his next act, Pedersen withdraws a jaw harp from his pocket and twangs a sea-chantey. Mrs. Pedersen is shaking her head back and forth gently as she rises to clear the dishes.

“Where’s the vihuela-player?” Princess Anne wants to know.

The vihuela-player is asleep in Pedersen’s barn loft. He sleeps the rest of that day, and all through the night, awaking in the morning to the sight of the smiling George Keith staring at him from an upper rung of the wooden ladder leading to the loft.

Keith informs him that he is to have sole possession of the loft. Members of the Gideon’s crew who were to have shared the space with him have escaped to the mainland. Andrew is instructed to take his meals at the table of the Alfhid family whose farm adjoins Pedersen’s. When Andrew goes there, the widow Alfhid and her three chunky blond daughters, hair braided atop their heads, are pleased to have a male guest at table and smile collectively as he wolfs down his fir-bread and hemp nuts.

Back in Pedersen’s barn, refreshed by long sleep and nourishment, Andrew takes up the vihuela. Resentful of his inattentiveness in recent days, she is cold to his touch, but he knows from experience exercises will correct the situation, and begins playing. Sunlight through narrow cracks in the planks generates a soft, warm light, and the barn has a pleasantly sweetish smell compounded of hay and animal dung. The raw pine siding makes for wonderful acoustics.

* * *

News that his bride is on Flekkeroe reaches King James and stirs his remembrance of Leander who swam the Hellespont fearlessly to reach his inamorata Hero, virgin priestess of Aphrodite, and it occurs to him that shipping to Norway personally to rescue the princess would be a wonderful adventure. He broaches the subject with Lord Chancellor Maitland.

“Entirely too risky,” Maitland says. “If something were to happen to you, all hell would break loose here.”

It occurs to James that undertaking this mission without Maitland’s approval would demonstrate his independence of the man many regard as de facto ruler of Scotland. There would no doubt be danger in the excursion, of course, but if he were he to drown history would remember him as one of the world’s great lovers, and he would be spared a reign likely to consist of trying to pacify squabbling Scottish lords and prelates while fearing constantly poisoned whiskey or a knife in the back.

At Flekkeroe, word reaches Admiral Munk that ships other than the Gideon which survived the storm have been blown to various points along the Norwegian coast. The flotilla reassembles near Flekkeroe and launches for Scotland, but makes small progress before being blown back to the island again by another gale. A second attempt to sail a few days later meets with similar results. Munk, inclined previously to scoff at rumors of witches casting spells on the mission to Scotland, is no longer sure they can be ignored. In any case, he has had his fill of fir bread and hemp nuts, and the beer is running low. He orders the Danish ships back to Denmark for the winter.

The Scots hope to make further attempts to reach home with Princess Anne before winter, but while waiting the unusually numerous fall storms in the North Sea to subside they elect to relocate to the more comfortable surroundings of Oslo.

Andrew, unaware of the ships’ departures, enjoys meals and sociable palaver with the Alfhids, and takes long walks along the coast with Ingrid Alfhid. To hear him play while she works, Ingrid works in the hemp field nearest the Pedersens’ barn during the harvest. Andrew attracts a various barn audience: a Maltese cat who purrs intensely, cooing pigeons roosting in a corner brace, a trio of field mice all ears atop a bale of hay. One evening a fearless white moth alights on the vibrating soundboard and contemplates Andrew with beady black eyes.

Andrew is experimenting with imitations on the vihuela of mouse chitter, cat purr, donkey bray, and owl hoot.

King James, having made covert arrangements for a personal quest of Princess Anne, enters the North Sea with six ships and three hundred sailors–better equipped than Leander had been. Two of the ships go down in storms, and sailors die, but the King reaches Flekkeroe where he learns that Princess Anne is in Oslo. He dispatches his chaplain David Lindsay there to arrange for an appropriate royal welcome and a repetition of the marriage vows, and expresses his desire that while on Flekkeroe he might sleep in the bed that had been Princess Anne’s.

Mrs. Pedersen sighs, puts a fresh loaf of fir-bread in the oven, and picks up her broom.

Lying in bed his first night at the Pedersens, James recalls that King Solomon, to advance his knowledge of the common people, roamed the rural countryside disguised as a peasant, and it occurs to him that while at loose ends on Flekkeroe he has a wonderful opportunity to do the same without the usual encumbrance of guards.

The next morning, in garb supplied by the amused Peder Pedersen out of his personal wardrobe, James hikes gaily from Høyfjellet, through Refsdalen and along Kjærlighetsstien to Bestemorsmed. In the afternoon, he lies beneath a sheltering rock by the sea, lulled asleep by the sound of the surf washing across pebbles.

Awakened by the mournful call of bitterns, and distant tinkling of cowbells, he is returning along a narrow path between the fields of the Alfhids and the Pedersens when he fancies hearing from a Norwegian barn what he cannot possibly be hearing: a work for lute by John Dowland with which he is familiar, and his sense that the place is enchanted is confirmed by the sight of the buxom, blond Ingrid Alfhid asleep in a furrow of the hemp field. His tongue falls from his mouth. He realizes that he is experiencing the Platonic “divine frenzy” of which Marsilio Ficino speaks that blends alienatio and abstractio of Saturnian origin with warm Venusian influences. Solomon, when he first laid eyes on the Rose of Sharon during his rural rambles, had undoubtedly experienced something similar.

* * *

When James steps from the carriage in front of the Bishop’s Palace at Oslo he is wearing a black velvet cloak lined with sable. His padded vest swells his torso, and when he removes his puffy high-crowned black hat to shake hands with the Bishop, he looks to Princess Anne standing nearby like a colorful beetle with small head disproportionate to its body.

The Bishop is delivering an ornate Latin blessing, when James spies the gangly, frowning young woman with frizzy yellow hair beside his friend George Keith — Princess Anne, obviously, though she bears small resemblance to the flattering pictures he has seen of her. He walks toward her dutifully in his shambling bow-legged gait, embraces her in a manly fashion, and attempts a kiss from which she turns away at the last moment, and his lips plunge into yellow frizz.

After the wedding vows are repeated, Anne goes to bed complaining of nausea and headache, and James in his private quarters at the Bishop’s Palace writes:

O cruel constellation which conspired

To seal my dismal fate before my birth!

My well-intentioned mother told her midwife,

“Spare no pains in bringing him to life.”

Her hopeful milk I drank a year and more;

And later, I imbibed inspiring waters

Drawn from Pierian spring by gracious Muses–

But lacked the ease to nurture fruits of wonder.

Born to royalty, a Scottish king.

A privileged lad, you say? The truth is rather

Job am I, whose patience Satan sorely smote.

Anne malingers, and as she and her new husband become acquainted while playing card games at bedside. She expresses her longing for music, and speaks of the admirable string player who was with the company on Flekkeroe. She wonders what has become of him. James recalls that Apollo is god both of music and medicine; that Democritus believed music could cure snakebite; and that music restored Odysseus to health after he was gored by a wild boar. He inquires with George Keith concerning the whereabouts of the musician of whom Anne had spoken.

Keith has a little talk with him about Andrew.

When the storms in the North Sea do not subside, and winter snows come early, the Scots abandon their plan to reach home before spring, and request permission to winter at Elsinore. King Frederick has been rejoicing in the dispatch of his madcap daughter to the hinterland, and does not relish the prospect of her rapid homecoming, but he dispatches sleds to Norway. In the dim light of a frosty morning, King James swathed in furs stands in a sled sheathed in black velvet and silver bangles and delivers a flowery valediction before a cluster of shivering, Oslo dignitaries.

The sleds depart in a blizzard and press on to Quille, and from Quille to Baahus Fortress on a cliff circled by a river at the Norwegian-Swedish border. Six hundred Swedish horsemen escort the entourage across the frozen Gotha-Elf and the Swedish Landflig, through Varbjerg, and Halmstadt. In the last leg of the trip, small boats convey the Scottish entourage down the Oresund to Elsinore.

Oh god, thinks Anne, I’m going to have to be seen with him in front of people I know.

The Danish royal family, and representatives of the court are milling around in the cold central court at Kronborg Castle as the Scots cross over the castle moat.

James meets for the first time his father-in-law and mother-in-law. “Amazing place you have here,” he says, looking around the court as he shakes the tremulous hand of King Frederick.

“The west wall was completed only last year,” Lady Gyldenstjerne puts in. “As you can imagine it has improved our security greatly. The fountain you see on your left is the work of Adriaen de Vriies symbolizing the Danish preeminence in the North Sea and the Baltic Sea.”

“Where’s Anne?” Queen Sophie inquires.

James looks around. “She was with us a moment ago.”

The Princess knows all the hiding places in the castle.

* * *

Fond as Andrew is of the acoustics in Pedersen’s barn, living there in bitter cold weather is impossible, and the Alfids have taken him in at their farmhouse where he is continuing to develop techniques for imitating on the vihuela the sounds of mice, cats, donkeys and owls that he is incorporating in a new solo work for vihuela, The Barn Suite.

* The vihuela, a precursor of the modern guitar, was played in Spain in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Tuned identically with the Renaissance lute, and close to the modern guitar, it had twelve strings (six pairs double-strung) rather than the modern six single-strung.

*A short dress-like garment with pleated panels.

* A pie made of custard and fruit.

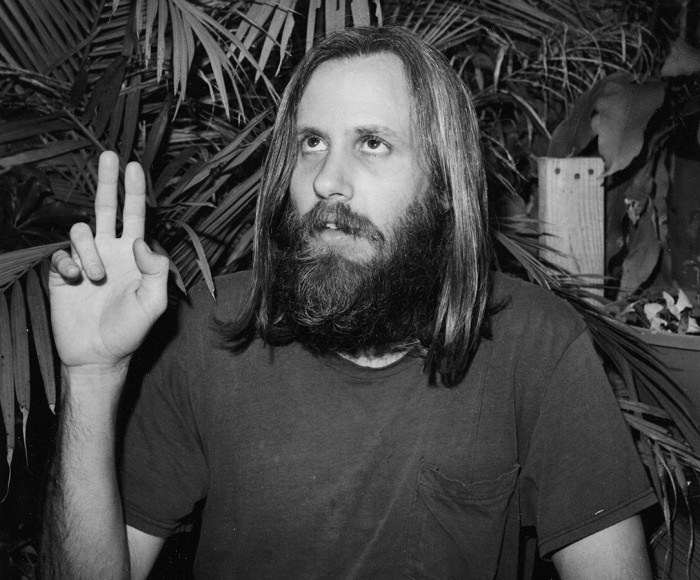

BIO

James Gallant, who lives in Atlanta, contracted the writing disorder at an early age, and has been basically incapable of making an income as a result. His disorder led to a fortunate marriage to income-producing university professor and Romantics scholar Christine Gallant who as a girl had romanticized the idea of marrying a writer. At times she had said later, “Be careful what you ask for.” Gallant attended graduate school at the University of Minnesota where he concentrated in Renaissance studies, traces of which survive in “Andrew the Vihuela-Player.” This story is one of nine short works involving historical classical guitarists–some (like Andrew) pure inventions, other based loosely on the lives of actual performers. Two of the other guitarist stories have appeared in other journals. The pieces as a group would make a good collection, Gallant believes, if anyone were interested in publishing it. Grace Paley’s Glad Day Books published his The Big Bust at Tyrone’s Rooming House/a Novel of Atlanta in 2004, and his essays and fiction have appeared in a number of magazines, including The Georgia Review, Epoch, Massachusetts Review, Story Quarterly, Mississippi Review, Exquisite Corpse, North American Review, Raritan, and Witness. He has a short novel, Whatever Happened to Debbie and Phil, and a collection of thematically-related related creative non-fiction pieces, Visits in Time and Space, neither of which have publishers at the moment.

James Gallant, who lives in Atlanta, contracted the writing disorder at an early age, and has been basically incapable of making an income as a result. His disorder led to a fortunate marriage to income-producing university professor and Romantics scholar Christine Gallant who as a girl had romanticized the idea of marrying a writer. At times she had said later, “Be careful what you ask for.” Gallant attended graduate school at the University of Minnesota where he concentrated in Renaissance studies, traces of which survive in “Andrew the Vihuela-Player.” This story is one of nine short works involving historical classical guitarists–some (like Andrew) pure inventions, other based loosely on the lives of actual performers. Two of the other guitarist stories have appeared in other journals. The pieces as a group would make a good collection, Gallant believes, if anyone were interested in publishing it. Grace Paley’s Glad Day Books published his The Big Bust at Tyrone’s Rooming House/a Novel of Atlanta in 2004, and his essays and fiction have appeared in a number of magazines, including The Georgia Review, Epoch, Massachusetts Review, Story Quarterly, Mississippi Review, Exquisite Corpse, North American Review, Raritan, and Witness. He has a short novel, Whatever Happened to Debbie and Phil, and a collection of thematically-related related creative non-fiction pieces, Visits in Time and Space, neither of which have publishers at the moment.

Anna Boorstin grew up riding horses, playing board games and reading. After attending Yale, she worked as a sound editor on films such as Real Genius and Clue. She raised three children and is happy to have (finally) found her way back to writing. Her story, Paper Lantern, made the Top 25 of Glimmer Train’s August 2013 Award for New Writers and was recently published in december magazine. Her Lizard Story was in Fiddleblack. She also blogs at Yalewomen.org.

Anna Boorstin grew up riding horses, playing board games and reading. After attending Yale, she worked as a sound editor on films such as Real Genius and Clue. She raised three children and is happy to have (finally) found her way back to writing. Her story, Paper Lantern, made the Top 25 of Glimmer Train’s August 2013 Award for New Writers and was recently published in december magazine. Her Lizard Story was in Fiddleblack. She also blogs at Yalewomen.org.

Jon Fried has published short fiction in Third Bed, Eclectica, Bartleby Snopes, Beehive, Pierogi Press, Pindeledyboz, Map Literary, Scissors & Spackle, Lamination Colony, New Works Review, The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review and Prick of the Spindle (soon) and other literary journals and e-zines, as well as songs he has written for a rock band he co-founded called the Cucumbers, which has released several recordings. He is working on a collection of stories about work called Transcendent Guide to Corporate America and a series of novels based on some colorful characters in his family tree. A Little Bit Closer to Water is set several years ago, so some of the media references are a little out of date.

Jon Fried has published short fiction in Third Bed, Eclectica, Bartleby Snopes, Beehive, Pierogi Press, Pindeledyboz, Map Literary, Scissors & Spackle, Lamination Colony, New Works Review, The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review and Prick of the Spindle (soon) and other literary journals and e-zines, as well as songs he has written for a rock band he co-founded called the Cucumbers, which has released several recordings. He is working on a collection of stories about work called Transcendent Guide to Corporate America and a series of novels based on some colorful characters in his family tree. A Little Bit Closer to Water is set several years ago, so some of the media references are a little out of date.

Evelyn Levine is a senior English major at Whitman College. A native of San Francisco, she hopes to one day be able to afford the rent. Evelyn enjoys spending time with her vocal cat Alan, baking for friends and family, learning Tai Chi, and playing the mandolin (albeit unskillfully). This is Evelyn’s first fiction publication.

Evelyn Levine is a senior English major at Whitman College. A native of San Francisco, she hopes to one day be able to afford the rent. Evelyn enjoys spending time with her vocal cat Alan, baking for friends and family, learning Tai Chi, and playing the mandolin (albeit unskillfully). This is Evelyn’s first fiction publication.

A. A. Weiss grew up in Maine and works as a foreign language teacher after having lived in Ecuador, Mexico and Moldova, where he served in the U. S. Peace Corps from 2006-2008. His writing has appeared in Hippocampus, 1966, Drunk Monkeys, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and Pure Slush, among others, and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He lives in New York City. Website:

A. A. Weiss grew up in Maine and works as a foreign language teacher after having lived in Ecuador, Mexico and Moldova, where he served in the U. S. Peace Corps from 2006-2008. His writing has appeared in Hippocampus, 1966, Drunk Monkeys, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and Pure Slush, among others, and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He lives in New York City. Website:

Veronica O’Halloran has taught English, Media Studies and Cultural Studies in high schools and colleges in Adelaide, Melbourne, and Los Angeles. She now lives in Cuença, Ecuador, where she is working on a book of short stories and completing a novel.

Veronica O’Halloran has taught English, Media Studies and Cultural Studies in high schools and colleges in Adelaide, Melbourne, and Los Angeles. She now lives in Cuença, Ecuador, where she is working on a book of short stories and completing a novel.

James Gallant, who lives in Atlanta, contracted the writing disorder at an early age, and has been basically incapable of making an income as a result. His disorder led to a fortunate marriage to income-producing university professor and Romantics scholar Christine Gallant who as a girl had romanticized the idea of marrying a writer. At times she had said later, “Be careful what you ask for.” Gallant attended graduate school at the University of Minnesota where he concentrated in Renaissance studies, traces of which survive in “Andrew the Vihuela-Player.” This story is one of nine short works involving historical classical guitarists–some (like Andrew) pure inventions, other based loosely on the lives of actual performers. Two of the other guitarist stories have appeared in other journals. The pieces as a group would make a good collection, Gallant believes, if anyone were interested in publishing it. Grace Paley’s Glad Day Books published his The Big Bust at Tyrone’s Rooming House/a Novel of Atlanta in 2004, and his essays and fiction have appeared in a number of magazines, including The Georgia Review, Epoch, Massachusetts Review, Story Quarterly, Mississippi Review, Exquisite Corpse, North American Review, Raritan, and Witness. He has a short novel, Whatever Happened to Debbie and Phil, and a collection of thematically-related related creative non-fiction pieces, Visits in Time and Space, neither of which have publishers at the moment.

James Gallant, who lives in Atlanta, contracted the writing disorder at an early age, and has been basically incapable of making an income as a result. His disorder led to a fortunate marriage to income-producing university professor and Romantics scholar Christine Gallant who as a girl had romanticized the idea of marrying a writer. At times she had said later, “Be careful what you ask for.” Gallant attended graduate school at the University of Minnesota where he concentrated in Renaissance studies, traces of which survive in “Andrew the Vihuela-Player.” This story is one of nine short works involving historical classical guitarists–some (like Andrew) pure inventions, other based loosely on the lives of actual performers. Two of the other guitarist stories have appeared in other journals. The pieces as a group would make a good collection, Gallant believes, if anyone were interested in publishing it. Grace Paley’s Glad Day Books published his The Big Bust at Tyrone’s Rooming House/a Novel of Atlanta in 2004, and his essays and fiction have appeared in a number of magazines, including The Georgia Review, Epoch, Massachusetts Review, Story Quarterly, Mississippi Review, Exquisite Corpse, North American Review, Raritan, and Witness. He has a short novel, Whatever Happened to Debbie and Phil, and a collection of thematically-related related creative non-fiction pieces, Visits in Time and Space, neither of which have publishers at the moment.

Carmen Firan, born in Romania, is a poet, a fiction and play writer, and a journalist. She has published fifteen books of poetry, novels, essays and short stories. Her writings appear in translation in many literary magazines and in various anthologies in France, Israel, Sweden, Germany, Ireland, Poland, Canada, UK and the U.S. She lives in New York. Her recent books and publications in the United States of America include: Inferno, novella, (Spuyten Duyvil Press), Rock and Dew, (Sheep Meadow Press), Words and Flesh, (Talisman Publishers), The Second Life (Columbia University Press), The Farce, (Spuyten Duyvil Press), In The Most Beautiful Life, (Umbrage Editions), The First Moment After Death (Writers Club Press). She is a member of PEN American Center and the Poetry Society of America and serves on the editorial boards of the international magazines Lettre Internationale (Paris-Bucharest) and Interpoezia (New York). She is the co-editor of Naming the Nameless (An Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry), Stranger at Home, Poetry with an Accent, Numina Press, and Born in Utopia (An Anthology of Romanian Modern and Contemporary Poetry), Talisman Publishers.

Carmen Firan, born in Romania, is a poet, a fiction and play writer, and a journalist. She has published fifteen books of poetry, novels, essays and short stories. Her writings appear in translation in many literary magazines and in various anthologies in France, Israel, Sweden, Germany, Ireland, Poland, Canada, UK and the U.S. She lives in New York. Her recent books and publications in the United States of America include: Inferno, novella, (Spuyten Duyvil Press), Rock and Dew, (Sheep Meadow Press), Words and Flesh, (Talisman Publishers), The Second Life (Columbia University Press), The Farce, (Spuyten Duyvil Press), In The Most Beautiful Life, (Umbrage Editions), The First Moment After Death (Writers Club Press). She is a member of PEN American Center and the Poetry Society of America and serves on the editorial boards of the international magazines Lettre Internationale (Paris-Bucharest) and Interpoezia (New York). She is the co-editor of Naming the Nameless (An Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry), Stranger at Home, Poetry with an Accent, Numina Press, and Born in Utopia (An Anthology of Romanian Modern and Contemporary Poetry), Talisman Publishers.

Mitchell Krockmalnik Grabois has had over seven hundred of his poems and fictions appear in literary magazines in the U.S. and abroad. He has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize for work published in 2012, 2013 and 2014. His novel, Two-Headed Dog, based on his work as a clinical psychologist in a state hospital, is available for

Mitchell Krockmalnik Grabois has had over seven hundred of his poems and fictions appear in literary magazines in the U.S. and abroad. He has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize for work published in 2012, 2013 and 2014. His novel, Two-Headed Dog, based on his work as a clinical psychologist in a state hospital, is available for

Suzanne Ushie grew up in Calabar, Nigeria. Her short stories have appeared in several publications including Fiction Fix, Overtime, Open Wide Magazine, Conte Online and Gambit: Newer African Writing. She has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia, England where she received the African Bursary for Creative Writing and made a Distinction. She lives in Lagos, Nigeria.

Suzanne Ushie grew up in Calabar, Nigeria. Her short stories have appeared in several publications including Fiction Fix, Overtime, Open Wide Magazine, Conte Online and Gambit: Newer African Writing. She has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia, England where she received the African Bursary for Creative Writing and made a Distinction. She lives in Lagos, Nigeria.

he cameraman counted down from 5, the lights went up, but it was only after the host crooned “You’re watching Dr. Morgan” and the Caribbean music was cued that Jordan Bickwell’s lower back really began to sweat.

he cameraman counted down from 5, the lights went up, but it was only after the host crooned “You’re watching Dr. Morgan” and the Caribbean music was cued that Jordan Bickwell’s lower back really began to sweat. Jacqueline Berkman is a writer living in Los Angeles with a background in publishing and public relations. Her short fiction has also appeared in The East Bay Review.

Jacqueline Berkman is a writer living in Los Angeles with a background in publishing and public relations. Her short fiction has also appeared in The East Bay Review.

Samantha Eliot Stier’s stories have appeared in many literary journals, including The Faircloth Review, Black Heart Magazine, Infective Ink Magazine, Mojave River Press & Review, Citizen Brooklyn, Drunk Monkeys, Gemini Magazine, Spry Literary Journal, and Blank Fiction Literary Magazine, and were featured in L.A.’s 2014 New Short Fiction Series. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University Los Angeles, and lives in Venice Beach, California. You can visit her at http.//

Samantha Eliot Stier’s stories have appeared in many literary journals, including The Faircloth Review, Black Heart Magazine, Infective Ink Magazine, Mojave River Press & Review, Citizen Brooklyn, Drunk Monkeys, Gemini Magazine, Spry Literary Journal, and Blank Fiction Literary Magazine, and were featured in L.A.’s 2014 New Short Fiction Series. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University Los Angeles, and lives in Venice Beach, California. You can visit her at http.//

John Oliver Hodges has published two books of fiction: The Love Box and War of the Crazies. He lives in Brooklyn, and teaches writing at Montclair State University in New Jersey. “Ethel’s Mountain” is his second story to appear in The Writing Disorder.

John Oliver Hodges has published two books of fiction: The Love Box and War of the Crazies. He lives in Brooklyn, and teaches writing at Montclair State University in New Jersey. “Ethel’s Mountain” is his second story to appear in The Writing Disorder.

Charlie Brown

Charlie Brown

Lou Gaglia’s work has appeared in The Cortland Review, The Oklahoma Review, The Brooklyner, Prick of the Spindle, Waccamaw, Eclectica, Amsterdam Quarterly, The Hawai’i Review, and elsewhere. His collection of short stories, Poor Advice, will be available from Aqueous Books in 2015, and his story, “Hands” was runner-up for storySouth’s 2013 Million Writers Award. He teaches in upstate New York after many years as a teacher in New York City.

Lou Gaglia’s work has appeared in The Cortland Review, The Oklahoma Review, The Brooklyner, Prick of the Spindle, Waccamaw, Eclectica, Amsterdam Quarterly, The Hawai’i Review, and elsewhere. His collection of short stories, Poor Advice, will be available from Aqueous Books in 2015, and his story, “Hands” was runner-up for storySouth’s 2013 Million Writers Award. He teaches in upstate New York after many years as a teacher in New York City.

Norman Waksler has published fiction in a number of journals, most recently The Tidal Basin Review, The Valparaiso Fiction Review, Prick of the Spindle, Thickjam. Scholars and Rogues and The Yalobusha Review. His most recent story collection, Signs of Life is published by the Black Lawrence Press. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His website is NormanWakslerFiction.com

Norman Waksler has published fiction in a number of journals, most recently The Tidal Basin Review, The Valparaiso Fiction Review, Prick of the Spindle, Thickjam. Scholars and Rogues and The Yalobusha Review. His most recent story collection, Signs of Life is published by the Black Lawrence Press. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His website is NormanWakslerFiction.com