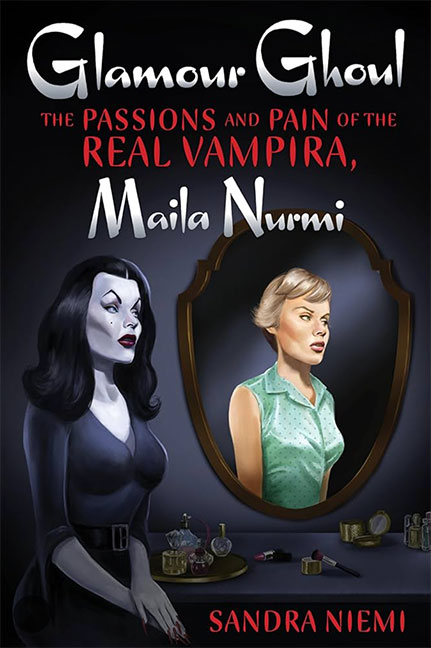

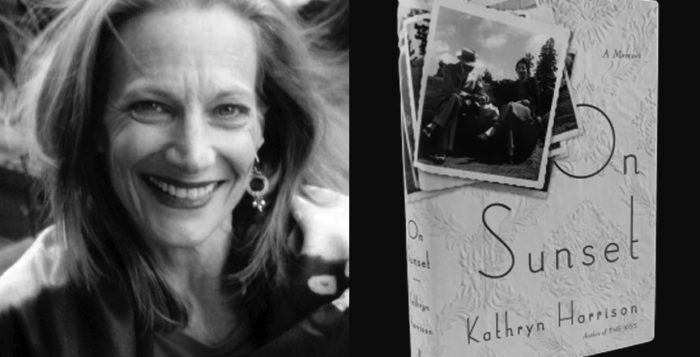

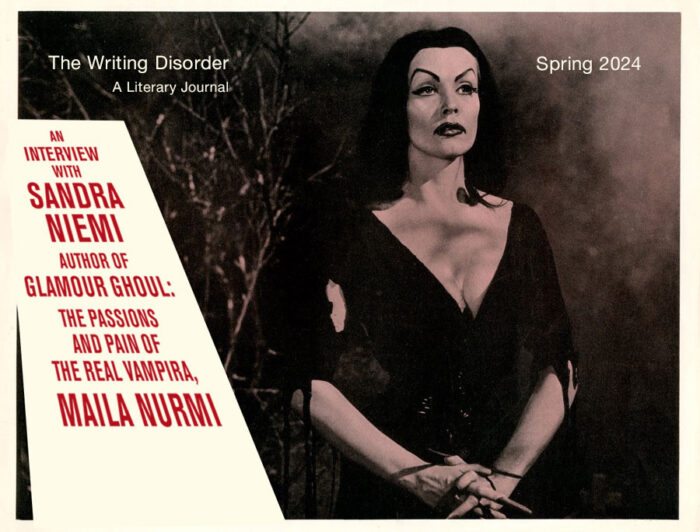

Sandra Niemi, author of Glamour Ghoul

THE INTERVIEW

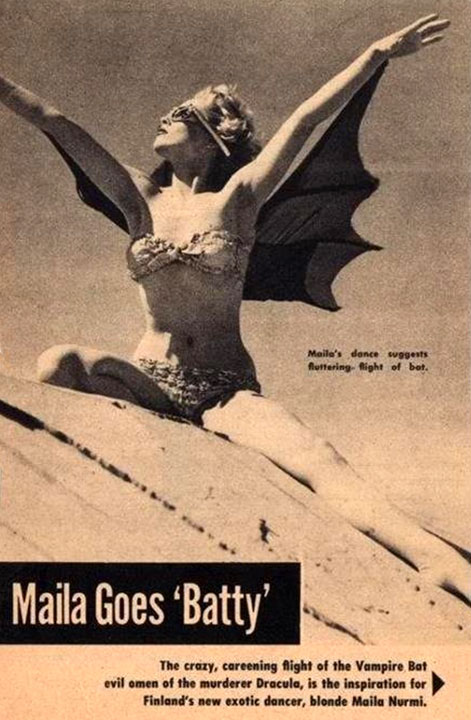

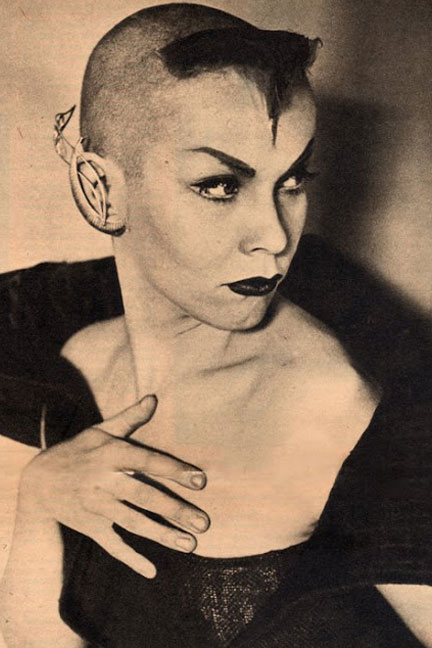

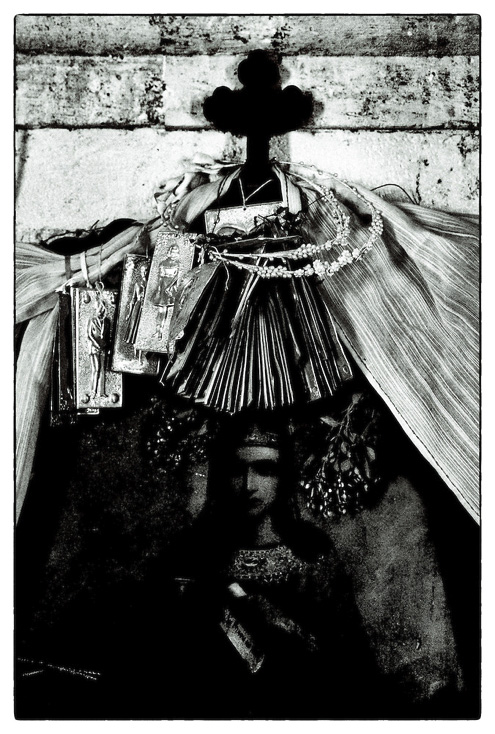

I’m a longtime fan of Maila Nurmi’s, the woman who created and played the legendary Vampira on TV and in movies. Although I don’t remember, my mom once told me that she took me to see Vampira in person when I was a little kid. I guess Maila did public appearances—in costume? Maila Nurmi was the host of The Vampira Show on ABC-TV back in 1954 in Los Angeles. Countless imitators followed her, borrowing and stealing from her unique look and style.

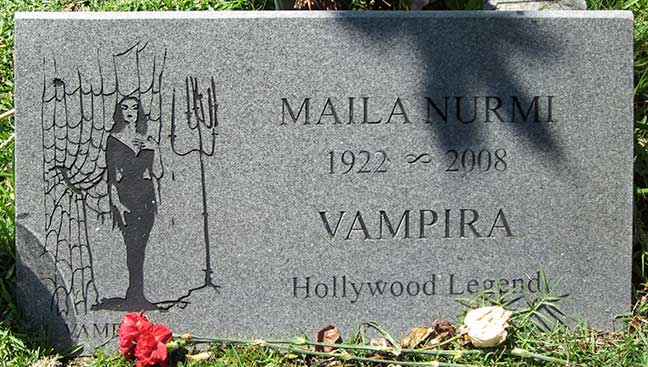

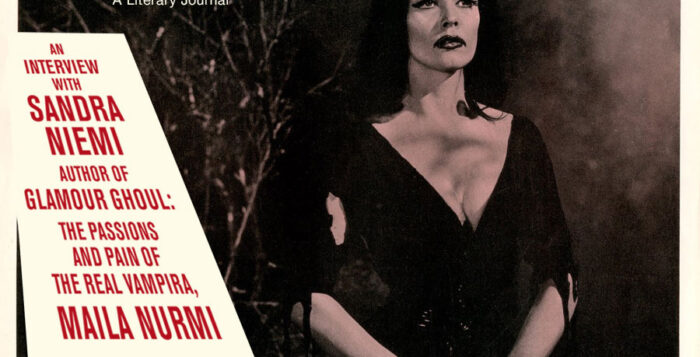

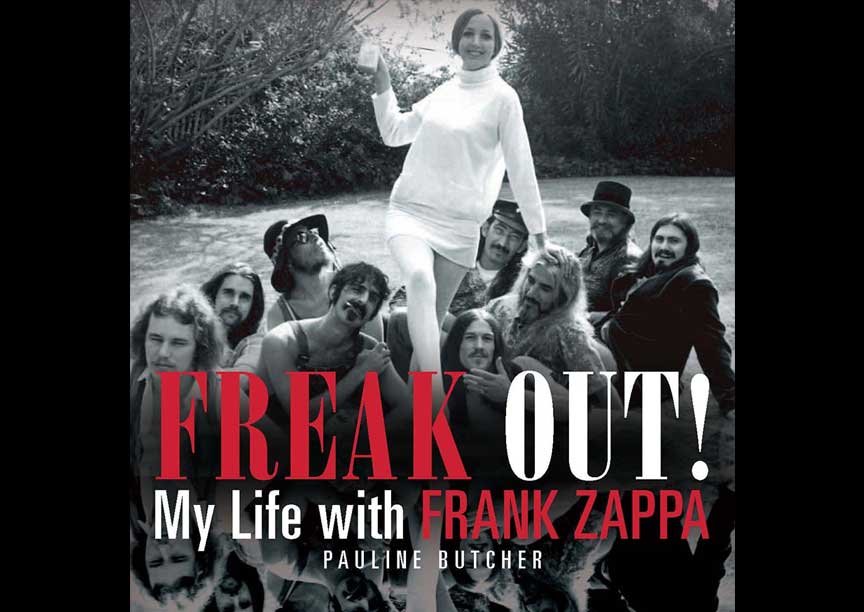

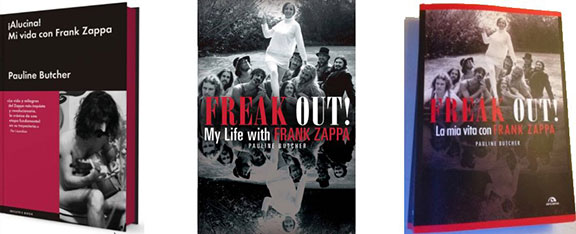

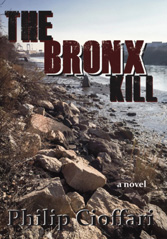

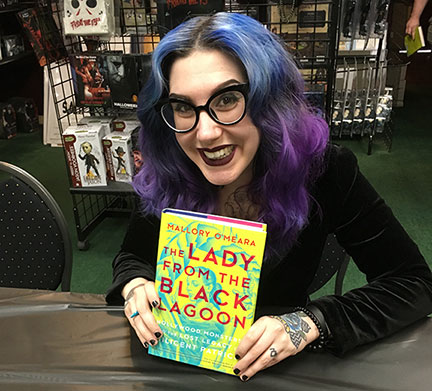

After reading the excellent book, Glamour Ghoul: The Passions and Pain of the Real Vampira, Maila Nurmi, that examines the extraordinary life of Maila Nurmi (1922-2008), the legendary TV host, actress and artist, I was curious to know more about the author. Sandra Niemi is Maila’s niece. When Maila Nurmi passed away in 2008, Sandra took control of Maila Nurmi’s writings and possessions. Ten years later, she penned a loving tribute to her famous fabulous Finnish aunt.

I was able to contact Sandra recently and she agreed to be interviewed for The Writing Disorder.

Tell us about yourself. Where are you living now?

Where the weather is mostly gray and cloudy. November is my least favorite month of the year. It’s dark and rainy and cold and the days are short. I live in Salem, Oregon, which is the capital. It’s a fairly good-sized town. I don’t know the population, but it’s a lot bigger than my hometown of Astoria that I lived in for sixty years. I sure do miss it, but the rain keeps me away.

How far is it from Salem?

Astoria is about two and a half hours north. I was up there recently for a Vampira celebration. It was a big success. They screened Plan 9 from Outer Space and they’re celebrating Maila because she graduated from Astoria high school in 1940. So the town is claiming her as an Astorian.

You grew up in Astoria, as well as your father, who was Maila’s brother?

Yes, my dad was Maila’s brother. He was 17 months older.

Did you know Maila growing up?

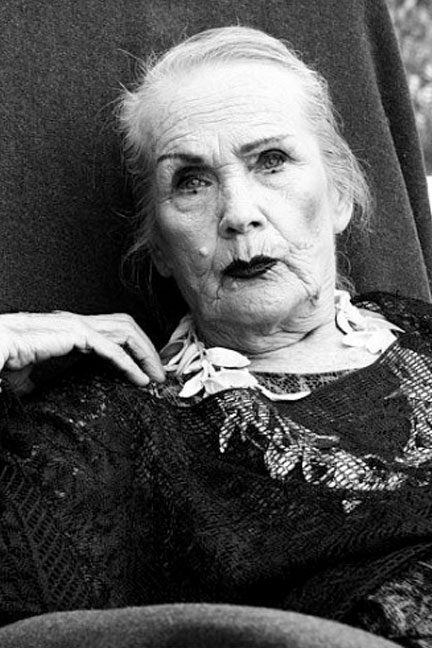

Not really. I met her when I was too young to remember. But I remember this, I must have been five or six at the time. My family went down to Los Angeles, and I saw her for the first time—and I was sure she was my own private Cinderella, because she was so beautiful. I had never seen such a beautiful human being in my life. It was in the daytime, I can still see her, she had blonde hair and she had blue eye shadow from her lashes to her brows, and bright red lipstick, a gold lame dress, and transparent shoes—which reminded me of Cinderella’s glass slippers. Then I didn’t see her again until her mother, my grandma, died when I was ten. And we went down to L.A. where they lived. Maila lived with her mother on Carlton Way. We were there for the funeral and Maila scared me. She reenacted how she found her mother dead in the chair that I was sitting in. But I didn’t know that, and she gave out this blood curdling scream that she was known for as Vampira and scared me to death. I ran out of the house. So, I thought that this was kind of a weird place to be, you know, it wasn’t like my little house in Astoria. And the strange thing is how Maila wore a black shift dress and dirty white slacks for two days. And then on the day of the funeral, or the day before the funeral, she asked my mother what she was going to wear to the funeral and my mother told her. And she thought, oh good, Maila’s going to change her clothes. But she didn’t, she just wore the same clothes again, and an old raggedy men’s navy-blue cardigan sweater inside out. Very odd.

She was a very independent and unique person—in her taste, her style, and with everything she did.

She was never afraid to display her different outlook on life, or to talk about it. She was very brave. And she just went about her life as she chose.

I read your book and it’s a really great story. It’s very well written. I kept asking myself, who wrote this book? I wanted to know more about you because I assumed you had written many other books, because it’s so good.

When I was younger in my 20s, I went to and graduated from Oregon State University, in 1969 when I was 22, and I majored in English. I always kind of fantasized about writing because I really enjoyed it. I received a lot of compliments from my professors, and good grades. And then life got in the way, and I worked my entire life as a minimum wage waitress, cannery worker, bartender, or house cleaner. I started out at 99 cents an hour and I think I ended at 8 or 10 dollars an hour. Oh, I worked 18 years at this job, the best job I ever had at the end. I worked 18 years as a medical lab courier. I went to clinics and hospitals and picked up specimens and delivered them to the laboratory. I never did anything with my love of writing until I got Maila’s writings. She didn’t have a typewriter, and this was before computers. She was a prolific writer, and it was all done in long hand. She wrote and wrote, and I gathered all of her papers together. And I thought, well, here is Maila’s story. I’m the only one who can write it. Maila and I had talked about it, when we were writing back and forth for three or four years, before we lost contact again. She said that she and I should do a coffee table book. Since she had been a house cleaner and I had been a house cleaner, she said, we’ll talk about the famous toilets that I cleaned, and you can talk about the rich timber barons and fishermen that you worked for. We never got around to it, but wherever she is, she is not mad at me.

It’s a great book. I would read it again because I enjoyed it so much.

It always shocks me, because we always put our own work down, you know, and have great doubts. Thank you.

Did she ever plan to write an autobiography?

Three times that I know of. I picked up in her apartment, after she passed, an old reel to reel tape and my friend got a player so we could hear what she said. She had spoken the words as a biography, and she had a friend there who was taping it. That was in 1966, so she was planning it then. And then she was planning it with another author, his name is Warren Beath, and he wrote a book about James Dean. He thought he was in contact with Maila, and then as Maila would sometimes do, she would erase the person from her life forever. She would not trust them, and she thought he was trying to steal her story and write her story himself. And then at the end I met this man, Stuart Timmons, he was the man who was with Maila day in and day out during the Elvira trial. He did everything for her, Maila never drove, of course, so Stuart drove her around wherever she needed to be, and he did a lot of the legal work that she needed done, because anything, like the clerical stuff, she had to do and he was also an author. She was telling him stories about what had happened in her life and he was taking notes and typing them up. And then she got to where she didn’t trust him, so she erased him from her life.

Now Stuart and I got together right after Maila passed away. We had lunch together, and we also were together every day. He helped me clean out Maila’s apartment. And, in fact, I found a box that Maila had written: To Stuart Timmons. And I said, Stewart, here is a box just for you. And he said, oh my gosh, and he got teary eyed. Inside was some jewelry that she had made for him. He was so thrilled to get it. And then we went to Maila’s storage unit with Dana Gould, another friend of Maila’s. Dana is the one who paid for her storage unit. And it was a big storage unit — it was packed to the rafters. You couldn’t put a hair pin in there it was perfectly packed to the door, to the ceiling, to the wall. And Dana said, oh my God, this is going to be a chore to go through, and I said, yes. He had a key and I had a key, and because I had to go back to Astoria to work, I gave my key to Stuart, because I totally trusted him. He was a wonderful man. In fact, I called him Uncle Stuart, because he told me he was my aunt Maila’s last gay husband. So, I called him Uncle Stuart.

Dana gave his key to a woman named Gabrielle Geiselman, who at the time had a boyfriend who was a bass player for Rob Zombie’s rock band. And he is still famous, he’s Matt Montgomery or Piggy D, is his professional name. Anyway, they broke up and Gabrielle moved to New Orleans. Stewart called me one day, and I have documentation of this. Stuart called me on the 26th of January 2008. I was in Astoria. And he told me, I think I found THE dress, Maila’s, and I found some hip pads and a waist cincher, and he says I’ll put them aside for you. I thought, oh, that’s wonderful because I’m coming back to L.A. for Maila’s memorial in February. So as luck would have it, five days later, Stewart suffered a massive stroke. He couldn’t speak. They didn’t expect him to live. He was hospitalized for over two years before he was able to come out. He has since passed away, but his brain was fine, but he could no longer walk. He had to be in a wheelchair, and you couldn’t understand what he said. But he was still writing books when he passed away. But when I went back to the storage unit in February, it had been ransacked and everything was gone all the way to one stack of boxes at the very back. So, I called Dana right away and said what happened to the storage unit? He said, Gabriel was there but you know she saved everything for you. There’s a box there for you and I rented another storage unit there that you put all the garbage in that you didn’t want. I said, Stuart, there’s one box here with a hat in it and that’s all. I was furious. And I couldn’t make Dana understand. I blame Dana for ransacking it, and there was a rift with Dana and me. And we didn’t speak for 10-12 years. We’ve made-up now. We’re friendly now, but now he realizes that Gabrielle was a thief. She took all Maila’s stuff, oh gosh—her bat sunglasses, her waist cincher, the dress, black wigs, her makeup, and all kinds of writings. Her marriage proposal from Marlon Brando — all the pictures, and she sold them to Jonny coffin. Jonny Coffin now owns them and the trademark. I get no money; the family gets no money from anything that Maila sells. Not a penny.

You know anything with Maila Nurmi on it that sells, Jonny Coffin gets it all because he owns the trademark. But he went and got it behind my back while I was still grieving my aunt and so yeah, he’s the owner of the trademark. Maila’s family gets nothing. In fact, he tried to stop the publishing of my book. He sent his lawyer to me. His lawyer threatened me and so I turned it into my publisher’s lawyer, and they got rid of him. But then Johnny turns around and says that he helped me write the book. Oh no, which is obviously a big lie. He contributed nothing except a letter from his lawyer saying that they were going to stop the publishing of Glamour Ghoul and that you owe him $30,000. For what, I don’t know.

His real name is John Edwards, and he’s married to a woman named Linda Kay who is an actress and singer. Jonny is a big goth fan, and he hosts parties where he wears a Cape and a weird top hat. He has hair down to his waist and he has some kind of shop where he sells coffin-shaped guitar cases. He has girls dressed in bikinis and things advertising his guitar cases. And he sells a bunch of other stuff — plus all the Vampira stuff, of course, he sells now, and he makes pretty good money.

I think I saw him on YouTube. He was talking at Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

That’s where Maila is buried. Maila had her 100th birthday celebration last December in L.A. And I was there, and Jonny coffin, of course, wasn’t. He was terrified of me, so he didn’t even make an appearance.

I’m so sorry that all this happened to you.

We were very close for a while, Jonny, and me. He would call me a couple times a week, always professing to be my friend and asking me advice—what color should I put in this advertisement, and what do you think about this? I guess he was just trying to get information from me. I don’t know. And then when I told him one day, after many years we had talked, in fact. I’ve met Jonny several times. I’ve had lunch with him and his wife in L.A. And we were friendly, but one night he called me in Salem, and I said to him, you know Jonny I have in my possession from when Maila was alive, a cease and desist letter from her attorney to you, because you were proposing to introduce a new Vampira doll and Maila wasn’t going to have anything to do with that. And she told him in the letter, she said she never wanted Jonny coffin to have anything to do with Vampira, and he hung up on me. He never talked to me again because he knew the jig was up. Maila hated him in life.

I think that book The Vampire Diaries was put out by him.

Yes. It’s mostly newspaper clippings, I think. When I went back to his shop in 2009, he showed me a three-ring binder with all these newspaper clippings of Maila’s career that he had bought from a man named Chad, and he had paid $300 for it. A lot of those articles were in that book. I haven’t bought the book, but a friend of mine in California did buy the book, and I leafed through it. I wasn’t going to read it. I don’t know how many of Maila’s writings were in there, but they were all stolen property that Gabrielle stole. If Maila knew this was going she’d be so mad. I know she’d be on my side. So, I don’t know where it’s all going to end but that’s where it is now. And Jonny has no family. He has his wife, but his mother, father and sister have all passed away. And he and his wife have no children, whereas I have a daughter and two grandchildren that I have to live for. And then I have also met Maila’s son, David Putter.

Yes! Are you still you still in touch with him?

Oh, yes! I just called him. He left me a text message last week. He’s learning how to message. He’s going to be 80 in March, and I’m 76. I’m going to be 77 in May, and he’ll be 80 in March. So, we’re all Oldtimers. Yes, I’ve met him, and he’s got his mother’s eyes, exactly the same color and everything—that brilliant blue. We got along really well. He was an esteemed attorney for 50 years. It was celebrated with a lifetime achievement at the ACLU. He was at one time the assistant attorney general of Vermont. He has some things that he changed in the courtroom that are still law today in Vermont. He’s a very esteemed attorney. Maila would be very, very proud to know that.

Has he ever tried to reach out to the other side of the family?

Well, he’s looking to see who his dad is. He asked Orson Welles’ daughter for DNA, but he hasn’t heard back yet. But he’s trying to find out for sure. We don’t know for sure. We just know what Maila said. We weren’t there so we don’t know for sure. But I put it in the book because that’s what Maila said. Everything she said was put in italics in the book. You know she was a brilliant writer herself.

I remember her writings in your book. I liked the way she always used an ampersand.

Yes. I was really impressed by how she expressed herself, and I thought this is too good to paraphrase, I need to put her words down word for word so she can tell her story right. So that’s how it all happened.

You spent a lot of time researching this book.

Oh, I forgot to tell you that in 1989 I spent a week with her in Los Angeles and that’s the last time I saw her. We had a great time, we got along together. We dined out every single day and we got drunk together.

Those were the good old days — 1989 in Los Angeles.

It was August, the last week of August of 1989.

She was living in East Hollywood.

She was living at a place on Hudson Ave. and it’s no longer there. They raised the house and the garage that she lived in. There’s an apartment house there now. She was evicted but she got $5,000 to move, so that helped her.

And she had a store on Melrose Ave.?

Yes, she had a store. She went to garage sales and bought things and brought them back to her store and resold them. And also when she was on Melrose—she was a great seamstress—she made clothes for rock stars, during the hippie age, when they liked pantaloons and feathers and sequins and things like that. She would make costumes and people bought them. And she made jewelry. I still have many pieces of her jewelry, many pins that are signed Vampira on the back.

She also did some painting and artwork?

Yes, she did, and they were stolen—every single one. I know for a fact that when I looked at the storage unit before it had been ransacked, there were many paintings and they were covered with paper and they were propped on either side of the door. And when I came back, they were all gone. A year later I picked up a copy of Spin magazine. I don’t think it’s in print anymore, and there was a two-page color layout of Rob Zombie displaying his favorite things, and two of them were Maila’s, two of her paintings. He said he bought them from Maila’s estate. And I thought, no, you bought them from Gabrielle Geiselman, who’s the girlfriend of your guitarist Matt Montgomery aka Piggy D. So, she sold at least two paintings that I know of to Rob, and he has money, so she probably sold them for $1,000 each. They’re probably worth more now.

I’m assuming they’re worth a lot more.

I own one of her paintings that’s small. I got it is from a friend of Maila’s. They were very good friend towards the end of her life. His named is Greg and he connected with me, and I connected with him, and we talked. He sent me one of his paintings of Maila’s for free. It’s on my wall. It’s very nice. I love it. I had it professionally framed.

Beyond her personal diaries and her own writings, what other research did you do?

I interviewed Hilda, she was the woman who found Maila when she passed away. And I, of course, interviewed Dana, and the man who wrote Vampira and Me, R.H. Greene. And also, her second husband. His name was Farbrizio Mioni, he lived in Calabasas. When I was in Los Angeles, I just dropped in on him on a Sunday morning. He came to the door in a bathrobe, and he graciously invited me in the house. So, I got to visit with him. His last name was Mioni, and he and Maila were married in 1961 and divorced in 1964. He was 79 years old at the time and he has since passed away. I got the impression that it was just a marriage of convenience. He was gay. Maila wanted so much money a month to stay married to him and he could afford it and so it worked out. They stayed married for three years. And there were other people that knew her. I can’t think of anyone now right off the top of my head, but people that knew her. I would contact them about Maila and take notes. That’s after I had decided to write the book. I didn’t think that at the beginning, you know, and then I thought I have to, I have to. I can’t let Maila be a sad footnote in horror history, right? She deserved so much more.

How long did it take you to write the book?

12 years. I was plagued by self-doubt. Who am I? You know I’m 70 years old and trying to write a book, my first one, and then I would write a couple more chapters and put it away for six months and think, well I’ve come this far. And I’d write a little more, and it just went like that. In fact, I didn’t write the entire book, I was on the last chapter, when I came home from the grocery store and my daughter said to me, who lives with me. She said, I know who Maila’s son is. I know his name. I know where he lives. and I know his phone number. And I said, you do not—come on, that’s not even funny. She said, it’s true, here it is here. His name is David Putter, he lives in Vermont. What happened was, a couple years before for a Christmas present, I had sent my daughter, you know that ancestry.com? I sent her that and she had sent it in, and so had David. And they matched them as first cousins once removed. Oh my God, give me his phone number right this minute, I said. And I called right then and there. I didn’t even have my coat off and David answered the phone. I never dared to dream I could find my cousin; Let alone talk to him. Because I have a very, very small family, and every family member is extremely precious to me. David has no children, and he was adopted, so he has a very, very small family too. So, the first question he asked me is, do you do I know who my mother is? And I said, do I know who your mother is? I’m writing her biography right now, and I’m on the last chapter. You couldn’t be talking to anybody else on earth who knows her better than I do. It’s Maila Nurmi, aka Vampira. And he goes, Oh my God! I waited 75 years to find out who my mother is, and she’s a vampire? He didn’t know who she was, so he immediately went on the internet and looked her up. I said, you can see your mother, you can go on YouTube, and you hear her talk. You can find out everything you want to know just by going on Google. And he was excited about that. He said, I never dreamed of this. And you know those Vampira statues that Maila had commissioned back in the 1980s? They are very, very rare now. I had one for me and I had an extra one. And I said to myself, all these years that I have been packing it around original in the box, never opened, I always said to myself, someday I’m going to find the perfect person to give this to. And I’ll be darned if I didn’t. I sent it to David, and he has it proudly displayed in his living room. Whoever comes over to visit him, he always says that’s my mom out there, and they go, no? and he goes oh yes, that’s my mother! I saw her statue when I was at his house. I went there a year ago in August and I saw Aunt Maila there in David’s living room. He says he feels her around him all the time. And I say well if Maila could be anywhere, it would be with David. And then I said, I thought I was almost done with this book, and I had one more chapter because I had just met David. So that was the final chapter of the book.

Yes. He is the last chapter in the book.

I mean, I was there, I had just gotten to the end. Well now it’s over, just a few more paragraphs. And then I met David. And so, it was just my Maila. I keep saying, you know 12 years it took me to write this book, and I’m saying well Maila said you’re not going to finish this book until you meet my friend. And the minute, the minute I met him, the book was finished. It’s just bizarre, isn’t it, how things work out?

How did you find a publisher? Did you have one from the beginning or did you find one at the end?

When I first started writing the book, I learned that Feral House published the book on Ed Wood, A Nightmare of Ecstasy, that the movie was based on. So, I thought, well Maila was in Plan 9 from Outer Space, and Ed Wood—she knew him. I wondered if they’d be interested. So, in 2009 I called up Feral House and I talked to a man Adam Parfrey, he was the owner. And I simply asked him, I told him I was Maila’s niece, she had passed away, and I was going to write a book. Would he be interested in a biography of Vampira? And he said, oh absolutely. I said, okay, thank you. And so fast forward 10-11 years. I called him up again and Adam had passed away, but his sister Jessica was running the business, so I talked to her. And she said, yes, send me the manuscript. So that’s where it went, that’s how that worked out. They took it right away.

Were you involved with the cover design and or any other aspect of the book?

No. I’m not thrilled with the cover, it was not my choice. That was all the publishers. The Passion and Pain of Vampira or whatever the cover says, that was the publisher too. I just wanted to say Glamour Ghoul. So, I didn’t have much input on any of that. No input, I should say. And now these Finnish filmmakers, ICS Nordic, that are in Finland, they’re just in love with the whole concept. They’ve had a contract for going on two years now. They’ve been working on a six-part documentary of the book, and they’re looking for money. They’ve been looking for money for a while, and apparently, they don’t have the money yet, but that’s where that is.

Did they get the rights to your book?

They have a contract. The first time it was for 18 months and that expired. Now they have another six-month contract and Jessica Parfrey has been through this situation with her books many times. She said this is normal for the course, when people try to find money. She’s giving them a lot of leeway.

They’re a company from Finland?

Yes. They’re from there, and because Maila’s from Finland—we’re 100% Finnish all of us. Her parents spoke Finnish at home, and my mother’s parents spoke Finnish at home, so we’re Finnish. I think there are a lot of blondes in Finland, but there are brunettes too. You can usually tell by their faces. They have small eyes and round faces and blonde hair. But Maila and I are similar, we don’t have a round face. We have the cheekbones. I can usually tell Finnish people by looking at their faces. Yeah, they’re Finnish.

Do you have any family in Finland?

I have lots of family in Finland, but I’ve never met them on my mother’s side. My mother was in contact with them briefly. And they sent pictures of our cousins and lots and lots of cemetery pictures. Fins are big on cemeteries. They visit the graves 12 months out of the year—they’re decorated. I laughed when I got the photos, I said, oh there’s the cemetery, grandma said, yes, we’re big on cemeteries. My grandmother on my mother’s side was the oldest of nine children. She came to America on one ship after the Titanic. She missed the boat. She had a ticket for the Titanic, but she was late, and missed the boat. So she had to take the next boat over in 1912. My grandfather was already here from Finland. They got married and my grandmother never got to go back home. On the other side, on Maila’s side, her father was born here but she had one sibling who was 20 years older, and he was born in Finland. When he was a child his parents moved to America. And Sofie was born here in Boston. She was born in Boston. She was a Fin with a Boston accent. She talked like the Kennedys. My grandfather came over here when he was 21. Maila’s dad.

Who were some of your favorite writers?

To tell the truth, in college I had to read so many books as an English major. I even took French. I had to read books written in French, which I couldn’t do now to save my soul. But when I got out of college, I said I never wanted to see another book as long as I live. Never. And I did not read a book for many years. I was sick of reading, and now I can’t live without having a book to read. I like biographies. So, I read a lot of biographies, but I also like true crime like John Grisham, John Sandford, and Lee Child. I’m reading Grisham now. I’m reading something about an island in Florida.

When you were a kid or a teenager, who were some of your favorite writers?

When I was a kid, I read all the Nancy Drew books. Carolyn Keene, I think she’s the one who wrote those books. I can remember sitting in the car when my mom and dad were working during the summer, and just avidly reading those books one after another. I had a collection of Nancy Drew books. All of them were a dollar a piece in those days. And I went to the library quite often and just randomly picked out books to read. I was always a good reader, you know, right from the get-go. I could read very well. I didn’t read much in high school because I had schoolwork to do, and I had to read schoolbooks. The only thing that comes to mind now is Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys (Franklin Dixon) books. I might have read some of The Bobbsey Twins. I read a lot when I was a kid.

What about television — what did you watch when you were growing up?

We lived way out in the sticks, so we had to get an antenna. We didn’t get a television until 1958. But I can remember watching a Miss America pageant, and Bourbon Street Beat. I remember watching Bourbon Street Beat and the writer was Dean Riesner. And I said, oh mom look—we called him Dink—Dink wrote this episode of Bourbon Street Beep. (He was Maila’s husband at the time.) And my mom just said, Oh well, good. But I remember Chet Huntley and David Brinkley news, and I remember the original Mickey Mouse Club.

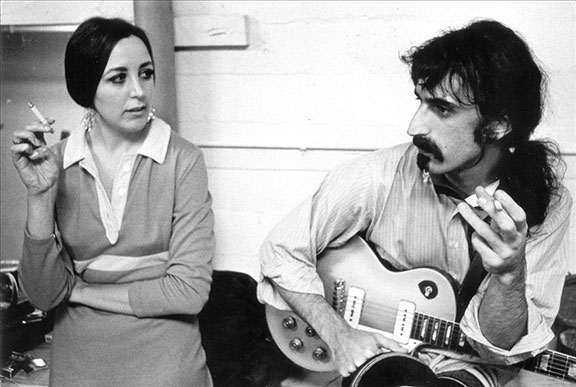

Dan Riesner was her husband?

Yes, we all called him Dink. I met him when I was a little kid. I remember sitting on his lap. I remember men in those days would flick the ashes from their cigarettes into the cuff of their pants. At the time that I met Dink he had on tan pants and a pink shirt. I remember he took us to a movie set where they were filming. We sat in the back, and they were filming a western. I think it was Amanda Blake or someone like that. There was a girl in a saloon. Then a production guy came around, I was standing by my mother, and the guy said, come on you’re on next, to me, and he grabbed my hand and took off. And my mother said, no, no, wrong kid, wrong kid. I told my mother years later that she had ruined my chance to be a star. We all went and played miniature golf after that, and I got to wear my Aunt Maila’s Cinderella shoes.

Dean was a successful TV writer?

A very, very successful writer. He wrote Play Misty for Me for Clint Eastwood. He wrote the movie for him and he was very involved with Clint Eastwood’s, The Enforcer. Remember all those movies he made in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. He even wrote the words, “Do you feel lucky, punk? Well, do you? Why don’t you make my day?” That’s Dean Riesner. He was very well known, and he was a script doctor. If somebody didn’t like a script, they called him to come in and fix it. Rich Man, Poor Man, the mini-series, he wrote that. He was very famous. He had no children, and he married a woman named Marie, and she passed away before he did. He didn’t have a family either.

How long was he married to Maila?

It was a common law marriage. They were together from 1949 until the first part of 1955. Dean was a hopeless alcoholic when Maila met him. And his career was down the drain, but Maila got him to quit—and his career took off again.

How many times was Maila married?

Twice. I never put the third husband in because I was never sure that they were actually married. She was married sort of married to Dean, I mean common law. And then she was married to Mioni. That’s the name that she went by legally. That’s how she got her Social Security checks, Maila Mioni. Supposedly she was married to John somebody. And I’ve heard there was a marriage license somewhere. But I never saw it, so I didn’t include it in the book. I think Maila and this John guy were just very good friends. So I didn’t include him. I think she was only married twice. And I’ve never been married, so I always say Maila was never really married, and neither was I. And we both have one child. I see a lot of parallels with my life and Maila’s.

Does your daughter or grandchildren have any resemblance to Maila?

No. My daughter is half Hispanic. As she found out with her genealogy. She always says, I’m 61% Finnish. I’m more Finnish than Hispanic. And it came back that her father was 10% Finnish. We never would have guessed. So, she’s 55% Finnish today, and her half-brother is 5% Finnish from his dad, from their mutual father. She’s 47 years old now. And I have two grandchildrenboth living in the Hawaii on differentislands. My granddaughter, she kind of resembles Maila. She would make a perfect new Vampira. She’s five feet, six inches, long dark hair, light colored eyes—very pretty girl. She would make a beautiful Vampira. She’s a bartender in Maui. She’s 27, my grandson is 24, and he works on the Big Island, Hawaii. I don’t ever get to see them because I can’t afford a ticket to get to Hawaii. That makes me sad. If I had the trademark for Vampira, I could afford to go see them. But I don’t.

So, you can’t use the name Vampira for anything because he got the trademark?

I guess I’m not supposed to. It’s okay to write a story about her because you know biographies happen all the time without trademarks. But I can’t sell any anything. I can’t go and have coffee mugs made with Vampira’s name or picture on it, something like that. I can’t do any manufacturing. I can sell things that I found in her house, because that’s like a gift you know. I can sell those, but I can’t manufacture anything and sell it like T-shirts. I can’t even do that.

That’s not right.

No, it isn’t. There’s nothing I can do about it, it would cost lots of money for an attorney, which I do not have the money for. Jonny was counting on that, I’m sure.

Maybe the publisher or someone like that could help.

We’ve had talks. Maybe in the future. I told them, well, you better hurry, because I’m 76, and you know I’d like to see it in my lifetime. But there isn’t anything yet. They have an attorney. The one who wrote the letter in the first place, when they threatened to not get the book published. I’ve met him, he’s very nice. I met him in Astoria this last weekend. He’s a very nice man. So, you don’t know. He kept telling me how important it was for me to attend the Maila celebration in Astoria. He said it was important and I don’t know why. I signed books. There was a Q&A. I have participated in that. I also participated in the signing of books and a Q&A in Los Angeles for Maila’s 100th birthday. So, I’ve done this twice.

When was that?

It was December 11th last year in Los Angeles (2022). I can’t remember the name of theater. It was at a perfect theater. It was supposed to rain like crazy that day, but it was beautiful sunshine on her day. It was in Hollywood. The American Cinematheque—that’s where it was, in Hollywood. It’s the old Egyptian Theater. That’s where we were.

I wish I would’ve known. I would have attended.

They declared it Vampira Day. It was officially named Vampira Day in Los Angeles. And now my biggest wish, my biggest wish, is for Maila to get a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

I can’t believe she doesn’t have one.

I know. I want to start a crowdfunding effort to raise the money. It’s around $55,000 to have a star. And then they have to vote on who gets to have a star that year, because not everyone does. But I think, for Maila, because it was officially called Vampira Day, that it really boosts her chances.

That would be great!

I keep saying that Maila walked the streets of Hollywood for 60 years, because she never drove a car. And for 38 years of those she walked with a cane because she had pernicious anemia. She had walked with a cane. And she walked a lot.

Later in her career, Maila was still appearing in movies.

Yes, she was doing movies, but was still being billed as Vampira. She was never billed as Maila Nurmi. Even though she wasn’t in a Vampira costume, she was still Vampira. As she got older, Maila liked being remembered as Vampira. For a while she tried to get rid of that image, you know like, I’m Maila Nurmi. And then she sort of became like a hermit, a recluse, and moved to the very, very east part of Melrose Ave. She moved from the west part, clear over to the east part. And she never told anyone that she was Vampira. In fact, in the book it says that Hilda knew her as Helen Heaven. And even when I was having lunch with Hilda, she always referred to Maila as Helen. And she knows that her name was Maila, but she always referred to her as Helen. That’s who Maila introduced herself as, Helen.

She lived on Melrose when it was like becoming trendy and popular with punks and new wave music in the 1970s?

She was there when the hippies came out. That’s when she lived there. I’ve gone past the house that she lived in. It’s still there. It looks like a two-story duplex. It might be four apartment units. That’s where she had her shop, in her living room. She didn’t rent a separate place. It had a big window in front. And it was her living room, so she just had that part as her shop. I just saw it in December again. I had some friends from Sacramento that drove down, so they were my wheels while I was there. And they’re interested in Maila too. They have a goth rock band called Ashes Fallen, and they have a song called Vampira that has over 10,000 hits. They’re big Vampira fans. They wanted to go to all the places where Maila lived, and we took pictures. It’s still there, and the little crappy apartment she lived in on east Melrose is also there. When we were there, it was a beauty shop. And, of course, the one where my grandma died, where Maila and grandma lived, It’s still there. It looks almost the exactly the same one. There’s a little fence built around it. A short little fence, and the apartment house next door has been torn down and a new apartment house has been built. And the fence that separated the properties is gone. That’s the same. I recognize that street so well. And then she lived on Gateway. I went up there and looked at that place. And then she died on Serrano and of course, they’ve completely torn down that and rebuilt it so it’s nice and new now. I remember Gabrielle had the key to Maila’s last house, and she did not want me to go back in there. And I couldn’t find her. I called her on the phone she wouldn’t answer. So, I called the managers, and they knew who I was by then. And I said I don’t have a key to Maila’s apartment, and I want to go in, and they said go ahead and break in. And I said really? They said how they were going to tear the place down anyway, so it’s okay—just break in the door. And I said, okay. Kind of funny. So, I was at the front door, and I was shouldering the door, and shouldering the door, and the guy next door opened his window and said, hey, do you need a hammer? Yes. I said, what kind of neighborhood is this where I’m breaking in and they’re offering me help? But Gabrielle had been there, and she had set aside a bunch of stuff on the floor that she wanted to take from Maila’s apartment. And I know she was there because she had left a satchel, an umbrella, and a hat of hers there, which I took. And the couch that Mila had died on, she had ripped open the back of it looking for money. That’s how she thought of Maila. It’s just sickening. And I have pictures of that.

Since you’ve written the book, have you learned anything more about Maila that wasn’t in the book? Are there any stories about her that didn’t get in the book?

There’s probably a couple. When I finished the book, the publisher wanted me to remove about 5,000 words. They wanted it to be shorter. So, I had to take some material out. And somebody said, now you have enough to write a second book. I don’t think I have enough for a second book. I have enough for a fiction book, but it wouldn’t be Maila. It would be some other name. I’ve messed around with the thought of me and Maila being in a book, but fictionalized. It would have Jonny and Elvira. I’ve pictured it. They would be the enemies of the book. Jonny would be running around Los Angeles, but instead of that costume that he wears now, he would be wearing one of those bird heads that doctors wore back in the day, when it looked like a crows head, when they had the plague, and they had to take care of people with the plague. They were those things that looked like a bird heads. That’s what Jonny would wear around Los Angeles, you know, and we get them in the end. I don’t know if it would sell. That’s the whole thing it’s just kind of a comedy, and not really, but I could put my personality in it.

It sounds like it would be make a good graphic novel. You’re not into the Goth scene, are you?

No, I’m not Goth. But I have friends who are Goth. They never wear anything but black. And my friend is the best Gothic baker you ever saw. She can bake anything. She can make a cake look like anything. I like the Goth scene. A lot of the people who came out for the Astoria Maila Nurmi show and the Los Angeles Vampira show were Goths. Very, very interesting outfits that they wear. And I like it. Maila is the original Goth creator—the mother of Goth. When she got older, she would say I’m the grandmama of Goth. She was the pioneer. And I had no idea when Maila passed away that she had so many fans. They’re all over the place. And I had no clue because to me whenever I saw Vampira, I would just say, oh there’s Aunt Maila in a black dress with a wig on. It was just my Aunt Maila in costume. I couldn’t separate them. It was all just one person. When I was with her in 1989, I didn’t ask her one question about Vampira. I just wanted to know her as a person. What’s your favorite color? What’s your favorite food? What do you like to do? What do you do with your days? How do you take care of your dog? What are you interested? Do you like to read? What’s your favorite TV show—things like that. Who is this person, my aunt? I didn’t ask about James Dean. I was here to find out who Aunt Maila was.

What was her favorite food?

Her favorite food was banana cream pie. Her favorite color was jewel tones. I assume she liked Ruby, sapphire, emerald—that kind of thing.

Who are her favorite performers?

I know that she hated Madonna and loved Cher. And I said, there we agree. I can’t stand Madonna, and I love Cher. And she hated in those days, at the newsstands, The Inquirer and The Star. She said all the photographs were terrible. They all had shiny faces. I remember that. She liked the TV shows, Three’s Company and Remington Steele. And if she could get an old movie on her TV, she’d like to watch that. She had a tiny little TV up on top of an armoire. That was her entertainment. I had sent her a little boom box that was my daughter’s. It was light blue, and I sent her some tapes. My father had been dead for 12 years, and I had a tape recording of his voice taken at a Christmas celebration. I sent her that and she really enjoyed that she got to hear her brother’s voice again. He sang the Finnish national anthem. He whistled and he talked, so I know Maila enjoyed that. And I still had a couple of letters that her dad had sent to my dad. They were written in Finnish and Maila could understand it. She could read it. So, I sent her copies of those letters. And I sent her a case of salmon, tuna and sturgeon, and a can opener. And a bottle of wine and a bottle opener one year for Christmas. So, I hope she liked that. I know she couldn’t cook. I think she had a heating plate to make coffee on. So, I sent her something that didn’t have to be cooked, and I know she liked fish. It was a wonderful, wonderful experience visiting with her. If I could live my life over again, I wouldn’t have come back in a week. I would’ve stayed and asked a lot more questions. Anyway, that was my time with Maila.

The photographs in the book, those were your photographs — or the did the publisher have to secure the rights to them?

I don’t know much about that. Some of them were my pictures, but I didn’t have much input on that aspect of the book either. I have a friend in Tennessee, who is a young man. He’s a huge Vampira fan that I befriended. In 2009, when I was in Los Angeles and met Jonny coffin at his place, Clint, and his mother, from Tennessee, flew out. So, I got to spend some time with them too. And Clint is a huge collector of Vampira memorabilia. He has lots of pictures. So he gave the pictures he had to the publisher. That worked out really well. I’m not that organized, and I have some pictures, but I don’t know where they are. The one that makes me the maddest of all, the one that I can’t find, is an 8×10 photo of Marlon Brando and Maila. It’s just the two of them. Maila is all decked out like she’s going to a party, in black dress, and Marlon is dressed like the movie, Desiree. He was a sea captain, or a military guy, and he’s dressed in costume and they’re together. I had looked for that picture for years, but I can’t find it. I think it still might be in the garage, and I’m hoping so. But I’m afraid to look anymore for fear I won’t find it. And so, there’s a lot of pictures in there—my most important pictures, and the letter from my grandmother is in there, too. The last letter she ever wrote before she died that I wrote about in the book. It’s in a three-ring black binder with a lot of Maila’s writings. I have not been able to find it. In fact, all the letters that she wrote to me, I had them when I wrote the book because I quoted from them, right, but I can’t find them now. Like I said, I’m not organized, I see something, and I just put it aside. And I’m not going to change at this age.

Who were the photographers who photographed Maila Nurmi?

Well, we know some of the photographers who took pictures of Maila in the 1950s. But we have no way of knowing who all the photographers were. I have no clue. There are family pictures of Maila, and her mom and dad, that I don’t have—and Jonny’s hanging on to it. That makes me mad. That’s my grandma and grandpa and my aunt. He has nothing to do with them.

Perhaps you could use some help organizing.

That’s why I have that friend in Sacramento. She is the most organized person I’ve ever met. She is really my archivist. I gave her all the stuff I had. She came up to Salem and I gave her everything I had. And she has cataloged and filed and put everything together and filed everything on the computer. She said this is all important Hollywood history, we have to preserve this. And she has. I’m really happy about that. Now everything is organized. Before everything was just in boxes. Everything works out. Maila found me, the archivist, and Maila made sure that I met her son. Maila is still working her Vampira magic. We don’t know for sure, but it seems that way.

She still has a presence in your life.

Yes. I still feel her around me. Once in a great while, not a lot, but once in a while, it feels like Maila is here with me. I think she spends a lot of time in Vermont now with her son. But she’s still working weird things. I mean, when my friend was here in Salem, and we were going through part of the garage looking for Maila’s stuff. It was September, I think. The garage door was open, and we were talking about Maila, and all sudden there was a huge cacophony of crows across the way. You couldn’t hear yourself talk. There had to be fifty of them in one tree. I’ve lived here for eight years, and it’s never happened before. And we both stopped talking, like what?! And we looked out and there’s all these crows. And my friend said, that’s a murder of crows. And I said yes. And then her husband showed up and we told him about the murder of crows. About a week later, I told you they have a Goth band. So a week later they were called up and asked to perform in New York City at a festival called Murder of Crows. See stuff like that is happening all the time. They went and performed this year in September, and now they have lots of new fans. They were number two on the Goth music list for their new album. They’re called Ashes Fallen. Michelle, my friend, plays keyboards, and her husband, James, is lead singer. The other guy in the band is named Jason. James and Jason have been friends for 30 years. They’ve played in the same band.

Thank you very much for your time. It’s been a pleasure talking with you. I wish you good health and happiness—and the rights to Vampira someday. I hope you get the rights back.

Thank you. It was nice meeting you too.

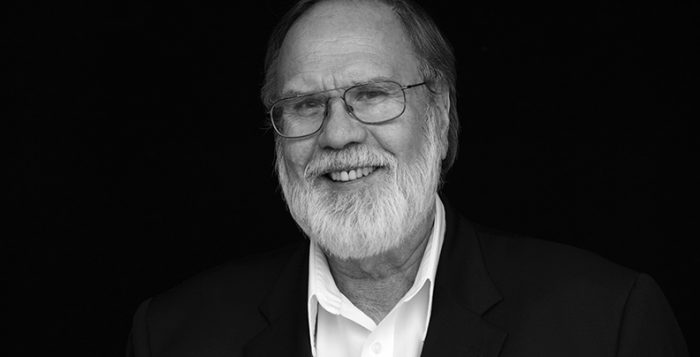

Dixon Hearne is the author of a textbook, three short story collections and editor of several anthologies. His fiction has been twice nominated for the Pushcart Prize and the Hemingway Foundation/PEN award and winner of many other awards. Other work can be found in Louisiana Literature, Mature Living, Wisconsin Review, Louisiana Review, Cream City Review, New Plains Review, Roanoke Review and many other magazines, journals and anthologies. Visit:

Dixon Hearne is the author of a textbook, three short story collections and editor of several anthologies. His fiction has been twice nominated for the Pushcart Prize and the Hemingway Foundation/PEN award and winner of many other awards. Other work can be found in Louisiana Literature, Mature Living, Wisconsin Review, Louisiana Review, Cream City Review, New Plains Review, Roanoke Review and many other magazines, journals and anthologies. Visit:

E.A. Vasallo – Archaeologist, young adult fiction writer, screenwriter and blogger. Awarded best screenplay 2014 – New Media Film Festival Los Angeles, California. Currently seeking publisher for novel. Bachelors of Screenwriting for Motion Pictures and Archaeology, UM. Resides in San Francisco.

E.A. Vasallo – Archaeologist, young adult fiction writer, screenwriter and blogger. Awarded best screenplay 2014 – New Media Film Festival Los Angeles, California. Currently seeking publisher for novel. Bachelors of Screenwriting for Motion Pictures and Archaeology, UM. Resides in San Francisco.

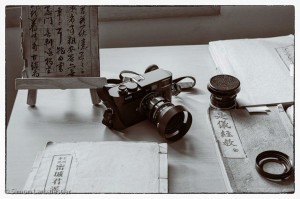

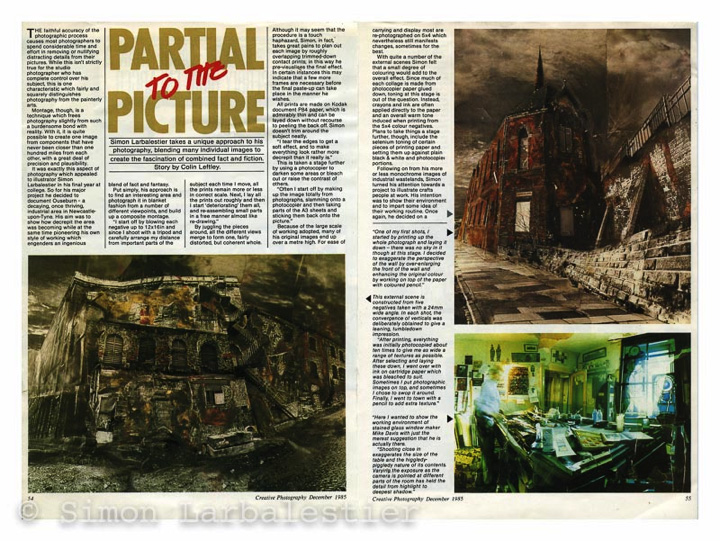

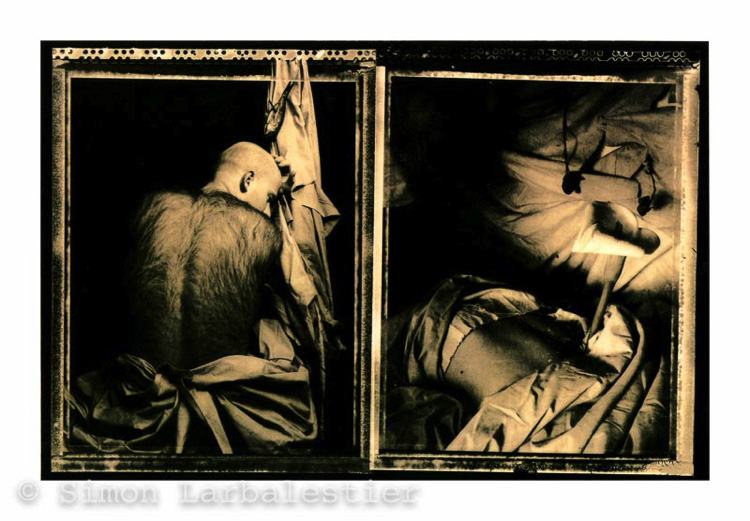

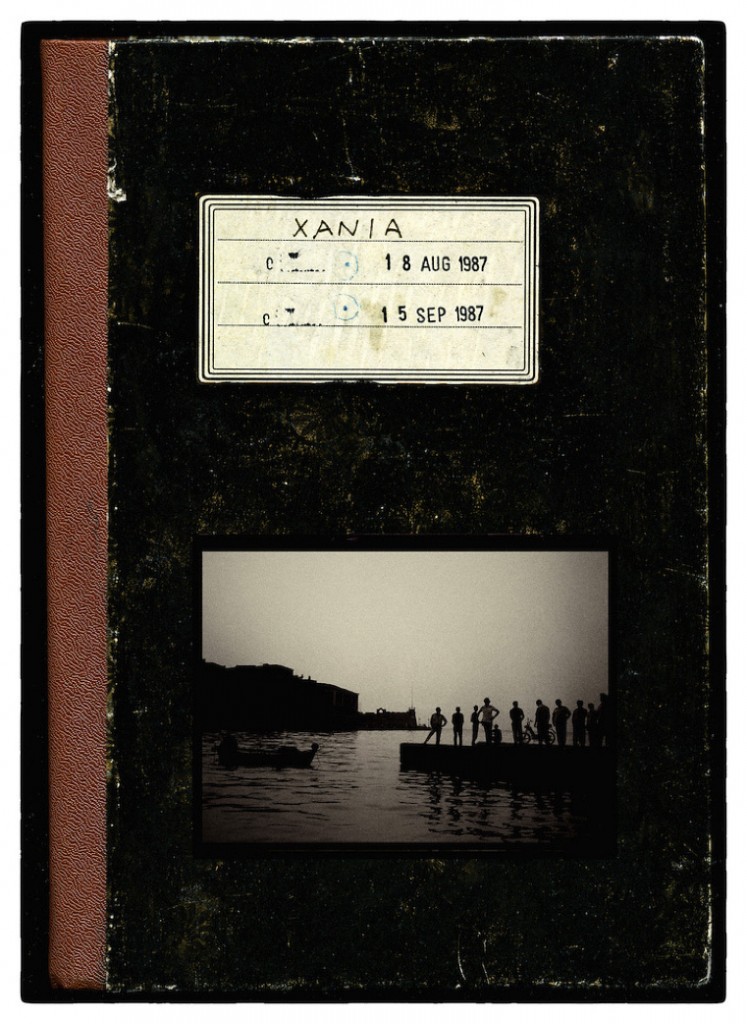

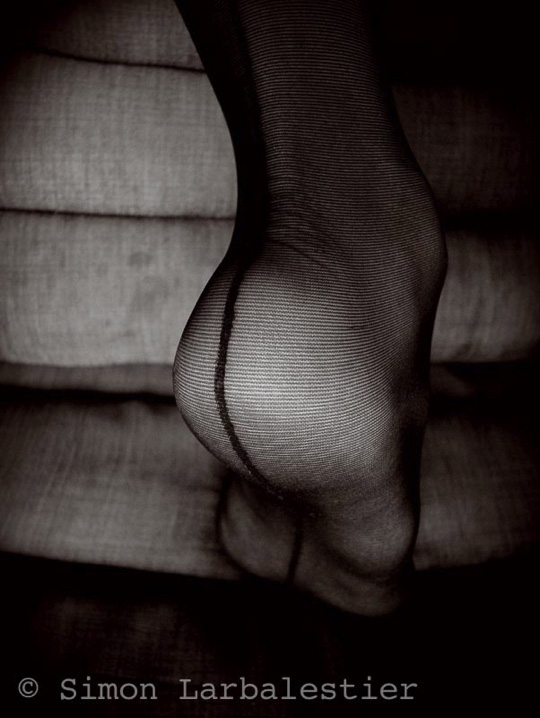

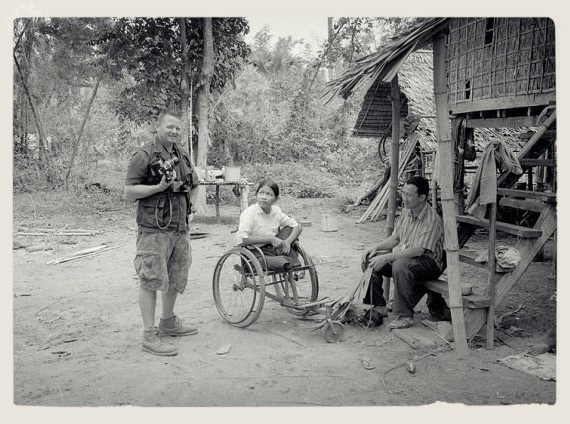

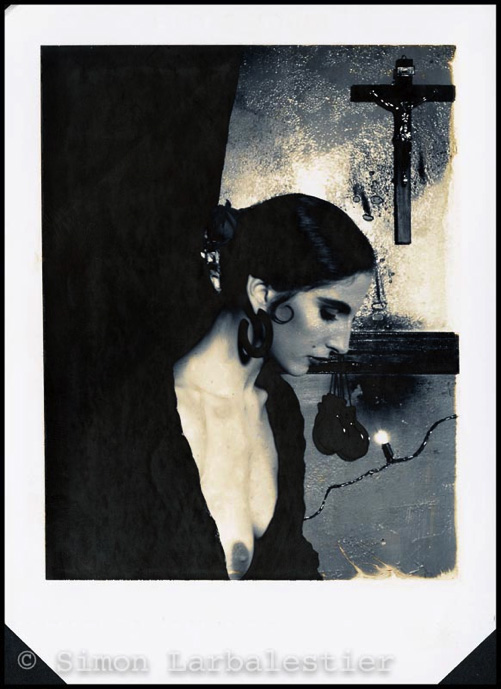

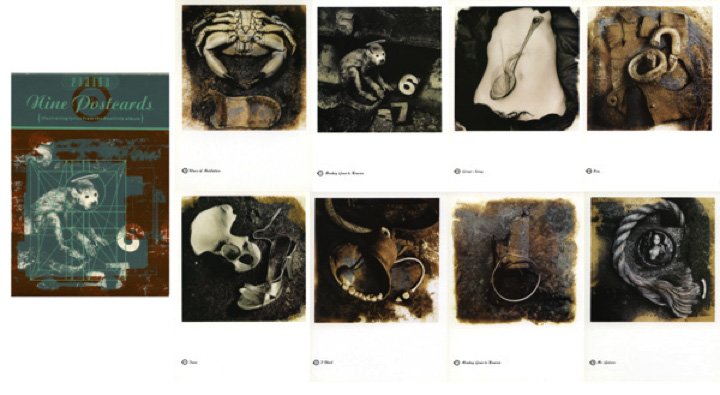

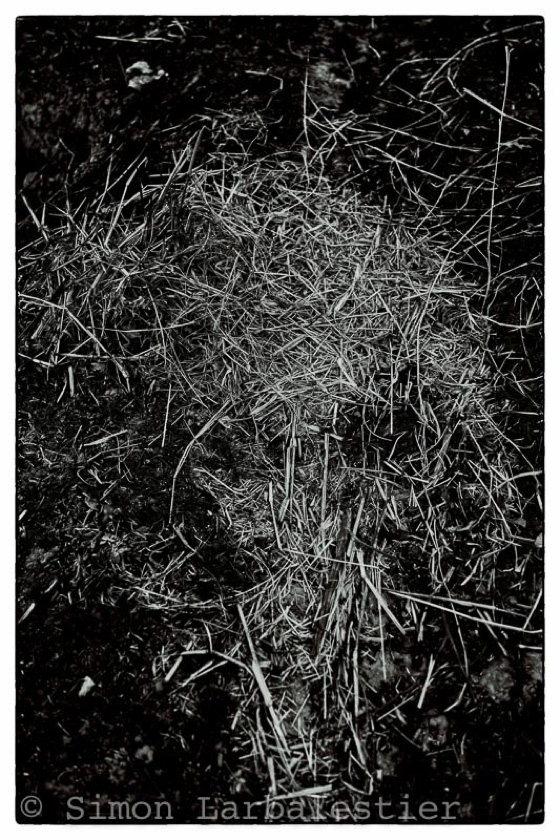

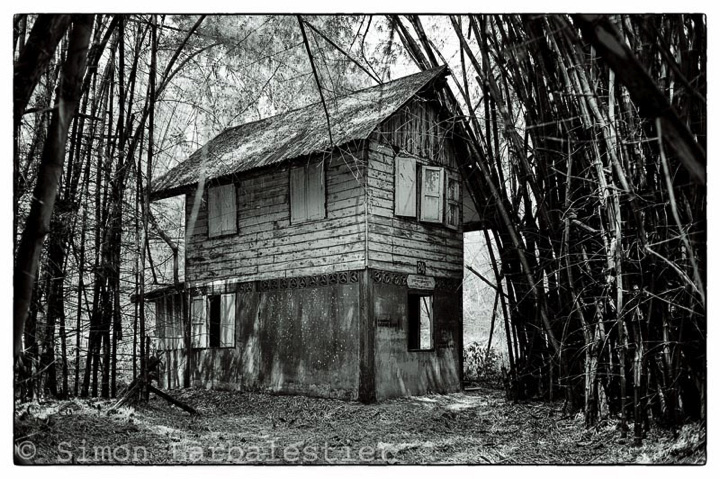

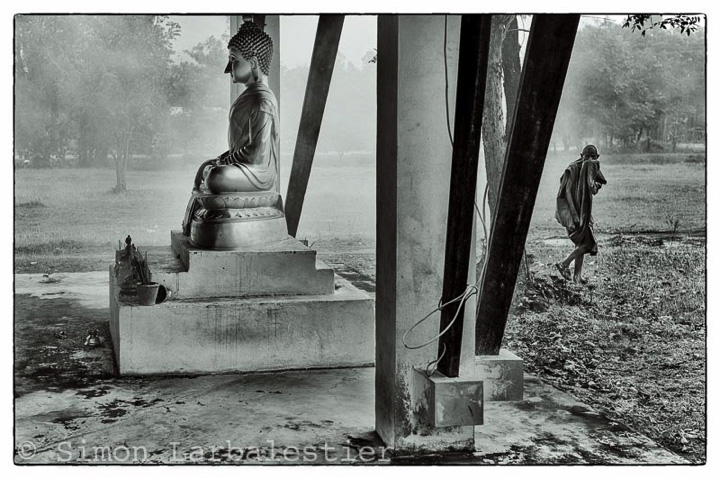

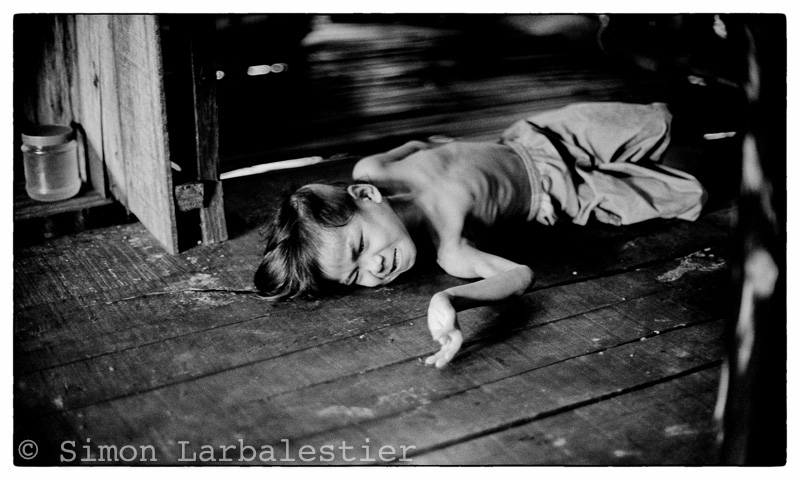

imon Larbalestier is without a doubt a master photographer. He’s been working at his craft for years, creating a body of work that is both inspiring and indelible. His style has influenced a generation of photographers. It’s a vision that puts him squarely in the class of great photographers. From his dreamy black and white images, to his stark, beautiful figures and locations, Simon creates a world you almost can’t describe. Known for his work with the iconic record label, 4AD, which began back in the 1980s, and for his images of remote, exotic lands, Simon’s work covers a wide range of topics and styles. We talked with Simon recently, to learn more about his work, and the creative process.

imon Larbalestier is without a doubt a master photographer. He’s been working at his craft for years, creating a body of work that is both inspiring and indelible. His style has influenced a generation of photographers. It’s a vision that puts him squarely in the class of great photographers. From his dreamy black and white images, to his stark, beautiful figures and locations, Simon creates a world you almost can’t describe. Known for his work with the iconic record label, 4AD, which began back in the 1980s, and for his images of remote, exotic lands, Simon’s work covers a wide range of topics and styles. We talked with Simon recently, to learn more about his work, and the creative process.

n interview with David Rose, “hidden gem of the British short story”. Author of Posthumous Stories (currently shortlisted for the 2014 Edge Hill Prize) and Vault: an “anti-novel”, his work has been described as “euphorically paranoid, slyly narrated, often hilarious” (The Guardian) and “deft, deliberate and utterly delicious” (3:AM). Here he’s generously answered some probing questions about the advice given to young writers, different artistic approaches, and what it means to have lived a “boring” life. Thank you, David.

n interview with David Rose, “hidden gem of the British short story”. Author of Posthumous Stories (currently shortlisted for the 2014 Edge Hill Prize) and Vault: an “anti-novel”, his work has been described as “euphorically paranoid, slyly narrated, often hilarious” (The Guardian) and “deft, deliberate and utterly delicious” (3:AM). Here he’s generously answered some probing questions about the advice given to young writers, different artistic approaches, and what it means to have lived a “boring” life. Thank you, David. Ruby Cowling was born in West Yorkshire and now lives in London, UK, working as a freelance writer for nonprofits. Winner of the 2014 White Review Short Story Prize and the 2013 Prolitzer Prize from Prole magazine, she was a finalist in the February 2014 Glimmer Train Short Story Award for New Writers as well as being Highly Commended in the 2012 Bridport Prize. Her recent print/online publication credits include The Letters Page, Unthology 4, The View From Here, and, in audio format, 4’33” and Bound Off. She is represented by Euan Thorneycroft at A M Heath.

Ruby Cowling was born in West Yorkshire and now lives in London, UK, working as a freelance writer for nonprofits. Winner of the 2014 White Review Short Story Prize and the 2013 Prolitzer Prize from Prole magazine, she was a finalist in the February 2014 Glimmer Train Short Story Award for New Writers as well as being Highly Commended in the 2012 Bridport Prize. Her recent print/online publication credits include The Letters Page, Unthology 4, The View From Here, and, in audio format, 4’33” and Bound Off. She is represented by Euan Thorneycroft at A M Heath.