The Death of Rhetta Brown

by Norman Belanger

i

Workshopped to Death

It was not her week to read. She knew full well it was not her week. Rhetta rose up from her seat at the front of the room, the sheafs of her manuscript fluttering as she wrapped a floral scarf around her neck. A current shivered the air, almost audible over the wheezing AC as Rhetta Brown stood defiant, oblivious to the ripple of ill will percolating around her. A clear breach of established protocol was happening, a coup. The people in their seats took turns giving Rhetta the fisheye and making faces at Peter Kaye to do something. It was Caroline’s week. They were all aware of that. It was the one rule of workshop at the Center: everyone gets a turn. And this was Caroline’s. Five pairs of eyes implored Peter to say something, anything, just stop Rhetta.

He did say something. That is, he tried. He would never understand why he let himself be intimidated by her, but he did speak up. “As a courtesy to the community, we try to ensure that everyone has equal time,” he said something to the effect of the rules and the respect extended to fellow writers, how everyone earned their chance, but he felt himself losing steam and by the end he was moving his lips but no sound came out because the woman had fixed him with such a look of impatience to be done with his little speech.

When he finished, Rhetta waved the air as if to erase what he had said. To her, it was noise. Static. She smoothed the pages of her opus, opened her mouth, and began to read.

“It’s really most humiliating,” Peter confided to Shaw later over their usual nightcap at the Eliot. “I never know what to do with her. The class is rightly irritated because I have lost control of the room. I’m supposed to be the instructor. Everyone expects to read. She runs roughshod over everybody, me included.” Rhetta had insisted on reading for the past three weeks in a row. And it was Peter’s fault for not stopping her. He sipped his drink, but his heart wasn’t in it.

“It’s not like you at all. You love telling people what to do.” Shaw hoped to tease Peter out of this rare funk, he’d never seen him so undone over a student.

“That’s the ridiculous part. I agree. I love telling people what to do. More than that, I love telling people to stop doing things I find annoying. But this person. She steps all over me.”

“Is she any good?”

Peter looked around, as if the lady in question was looming over his shoulder. “She thinks she’s a genius.”

“That bad?”

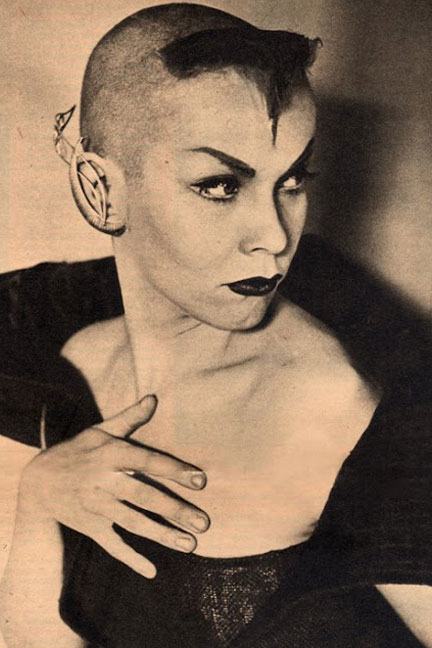

“The worst.” Peter wished he’d never met Rhetta Brown. There was a version of her in almost every workshop, but she had taken the role to master class level. Pushy. Rude. Dismissive of feedback other students gave earnestly, as if they could have no way of judging the magic of her words. And such words. There was not an overblown adjective she didn’t love, no adverb left unturned. And so many words. She consistently churned out 30-40 pages a week, an amazing feat for any student writer. But no problem for Rhetta, who once informed the class in all seriousness that she had been seized by an invisible power when she sat down to write, that her fingers were guided by an unnamed power as she banged out words like an amanuensis of the gods. So many words. Peter wondered if she used a laptop or a Ouija board.

Shaw, well into his cocktail, was practically busting with questions. Who must this Rhetta Brown be that she could subdue Peter Kaye, the formidable. Peter Kaye, cowed by a mere genius? “What does she look like? I want to picture her.”

“You’re really enjoying this, aren’t you? You love seeing me stymied.”

“Oh yeah.” Shaw motioned to Thomas for another rye.

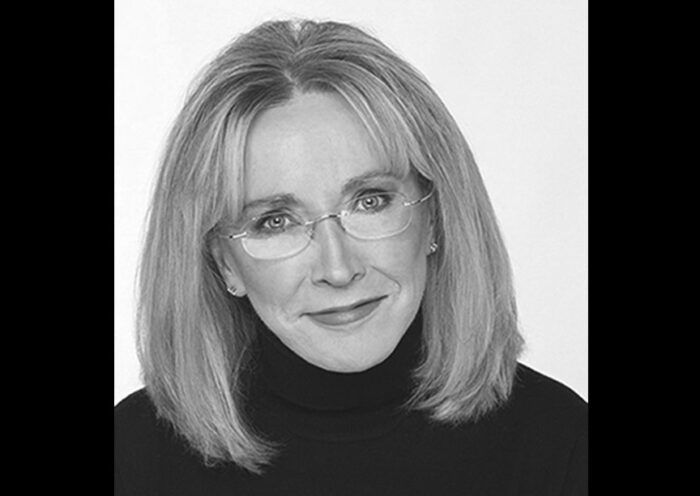

“Fine.” Peter put his glass down on its damp napkin. “She’s odd. Dresses in bizarre combinations of scarves and expensive shawls. Gaudy jewelry. Cambridge Artsy.”

“Sounds like a colorful character.”

“Not so much in real life.”

“What else?”

“She walks with a stick.”

“Like a cane?”

“Think more forest witch. Burled wood. Ornate. It’s all part of the act.” He finished his drink, disappointed. He’d hoped that venting to Shaw, having a nightcap in the usually soothing environs of their bar might help him shake off this feeling of weakness in spirit, this heavy shame that he’d let his students down by allowing one dilettante in cashmere to usurp his leadership of the class.

* * *

He’d been instructing Writing Murder is Murder at the Adult Ed for something like 12 years. Standing at the front of that room every Thursday afternoon was his happiness, the little rectangle of space where he strutted before a half dozen people who hung on his every word his stage. Here, he was beloved. The writers did not think him too short too fat too queeny too much; his students saw him as someone who loved talking with other writers about how they wrote, why they wrote, what they wanted to say. A handful of ladies, and one gay man, returned often, signing up for the class term after term, making the class a kind of family, a circle of friends. He kept the class size small to create that intimate environment, more like a salon, and this made signing up for the course something of a competition to break into. Cutthroat. There was a wait list.

On the first day of the term, he had read the class roster, noting that one familiar name, Martha Andrews, had a grim black line through it, and another handwritten in its place. Rhetta Brown. Had this been a movie, an ominous ripple of cello strings would have signaled a warning, but instead he read the name with no awareness of the cascade of trouble to come.

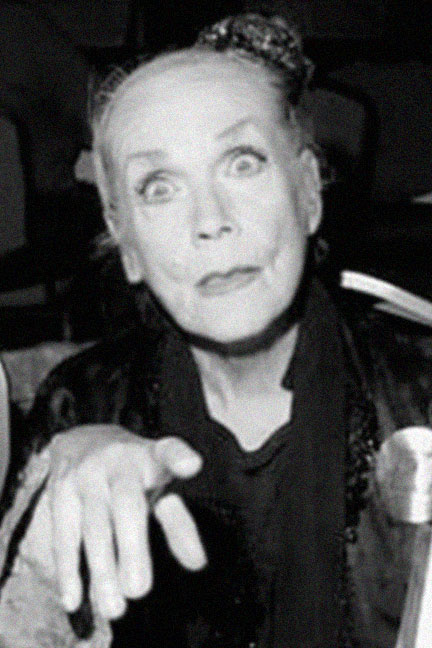

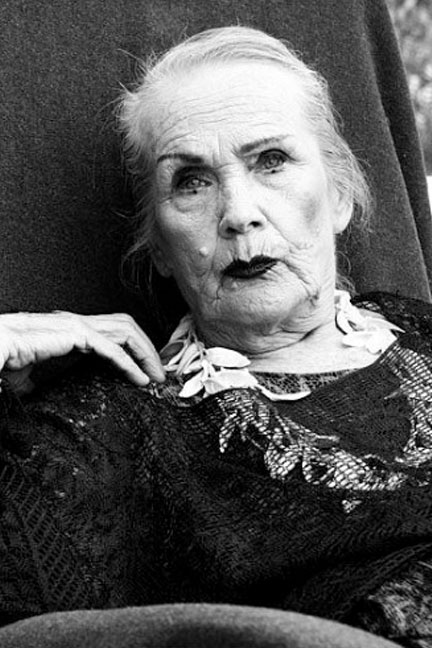

She came in full sail, swathed in yards of fabric and jangling beads, that witch stick ticking down eternity, the sound of impending doom. But he might as well have been deaf to it. Blind as well—he had seen how the regulars responded as the lady made her entrance into the room, tapping out her steps. Tap. Tap. Tap. Glacially. Slowly. Erect. You had to watch her, an unstoppable tug trudging into harbor.

Caroline, who had a fatal tell whenever she didn’t like something, crossed her arms over her chest and sat back in her chair.

Joseph, the lone male in a sea of doctor-prescribed estrogen, clicked and unclicked his pen.

The class elder June zipped up her fleece as if she felt an unwelcomed chill.

Peter Kaye saw all this. He’d even felt his scrotum retract deep within him at the sight of her, his reptilian brain sensed the predator when his ego did not. He had been an idiot. As soon as she finally dropped anchor and groaned into her seat, she opened a capacious bag out of which she produced what he would in time come to understand was her manifesto. So many pages. She was here to annihilate them all, one word at a time. One week at a time.

* * *

Shaw, saddened by the dejected look on poor Peter’s face, decided to relent his prodding. The situation had somehow humbled his friend in a way he’d never seen happen before. “I’m sorry, old man,” he said. “The term won’t last forever. It’ll end. Hopefully you’ll never be troubled by Mrs. Brown ever again.”

Peter shrugged. Maybe he’d met his Waterloo. Maybe it was time for him to hang it up, give up teaching. If one person could cause this much trouble, he’d lost his ability to run the class the way it always had. He could not bear to think about the looks on the faces of the others while he sat and did nothing. This occupied his thoughts as he said goodbye to Shaw on the corner, mechanically kissing his friend’s cheek, and it followed him on his short walk all the way home.

* * *

He was not surprised the next day when he was invited to meet up with Caroline and Joseph in the park for “an important discussion.” They were standing under a spreading elm next to a bench he assumed was intended for himself. He sat, like a witness in the box, and waited to be grilled. He did not need to wait long.

Without preamble or the usual niceties of greetings, Caroline went right into it. “You’ve got to do something about Rhetta Brown.” Caroline’s speech was like her prose: clean, efficient, nothing extra, nothing that did not advance the plot. “If you don’t take care of her, we will.” That did sound ominous.

Joseph, the diplomat, whose natural gracious manners won him the affection of most people he met, spoke in his usual soft voice: “Mr. Kaye, with all respect, please, we beg you. We are a community, and more than that, friends. She is not interested in being either.”

“It was my turn this week,” Caroline fumed, “I worked hard on my revisions, psyched myself up all week to read. I could’ve whacked her over the head with that stupid cane of hers.”

Joseph attempted to smooth the situation with a smile, “Back home, the old aunties would call this kind of person a ‘pig stuffer’. It loses in translation, but you understand.”

Peter didn’t know if he should laugh or submit to the sob that harbored deep in his chest. He was certain they were speaking on behalf of the rest of the writers, that the group of them all had huddled together to discuss what to do about Rhetta Brown, perhaps they even said amongst themselves that Peter Kaye had lost his ability to facilitate a class.

Joseph put a consoling hand on Peter’s shoulder. “Mr. Kaye. Please understand. We say this out of love.”

This was the cruelest blow of all. Peter bowed his head. He could accept their enmity, even their scorn he might understand, but that they should pity him, this he could not, would not allow. He stood up with such uncharacteristic rapidity of movement that Caroline and Joseph both took a step back in surprise

Peter said at last: “I am sorry. Sorry that I’ve let you down by my inaction. No, don’t say anything, Joseph, I know you want to make things more comfortable, but I deserve to feel the weight of what you have said to me. Believe me, I have been berating myself as well. I will find a way to make this right.”

He walked away, leaving the two of them wondering what he might do.

* * *

He got her number from the registrar. If Shaw were not sitting next to him, he would not have made the call. Even still, he sat with his hand on the phone for some time, unable to make himself go through with it.

“Maybe wait, until you feel up to it,” Shaw said.

Even his best friend acted like he was some feeble coot who had dulled his edge. This would not be borne.

He punched her number into his phone, listened to the line ring and then a horrifying click as Rhetta Brown picked up the landline. “Who is it?” she said, not by way of a greeting but more like a warning. When he could not respond immediately, despite Shaw’s nudging his arm, she demanded: “WHO IS THIS?”

In a hesitant croaking voice he did not recognize as his own, he began, “Rhetta? This is Peter. Peter Kaye from the Center?”

“Is that a question, or a statement of fact?” she said.

He tried again. “Mrs. Brown. This is Peter Kaye. I’m calling to talk to you about your recent conduct in the classroom.”

“What of it?”

He swallowed. Shaw nodded, encouraging him to keep going, a thumbs up for the promising start. “A number of students have brought it to my attention that they feel—”

“Oh I know where this is going. It happens. They’re jealous, naturally. Intimidated by the caliber of my output,” and here she allowed herself a chuckle, “it happens in every class I attend. I pay no attention to it, I advise you to ignore it as well.”

“But—”

“I know, it’s that Caroline person. She’s always looking at me. And that French fellow. Him too.”

“Joseph is from Martinique,” he interjected, pointlessly, as if she might care.

“They’re jealous. It’s so transparent.”

“Mrs. Brown. I need to speak to you about how we can bring a spirit of fairness to the class. Each writer wants the chance to read their work.”

“If you call the pap they produce ‘work,’ I think we’ll have a difference of opinion, Mr. Gay.”

“It’s Kaye.”

“Beg pardon?”

“My name. Peter Kaye.”

“Fine. Mr. Kaye,” she said as though his name was a negotiable point she was willing to concede. “I really can’t continue talking on the telephone much longer, I’m right in the middle of an important denoument scene to which I must return. When the muse strikes, you know—”

“How about we meet in person? Talk this out? I’d be happy to meet you at the Eliot, for a drink, it’s quiet there and we can have a conversation.”

“I’m not accustomed to meeting men in barrooms, Mr. Kaye. Even if I were, I can see no reason to discuss the matter any further.”

Peter felt his face get hot. Everything she said just made him angrier. She was condescending, a snob, a bully, and worse—a hack writer who thought she was the next Agatha Christie. “I’m afraid we are not finished, Mrs. Brown. We need to come to some kind of understanding before the next class meets. I insist it is of great importance that we do.”

Silence. She was not used to being challenged, and he could practically hear her thinking her next move. With an impatient sigh she relented, “My husband will be at a board meeting this evening. Why don’t you come to my home sometime after dinner. Say 7 0’clock?”

She was smart. Having him come to her place gave her the home advantage, but he didn’t care. At this point, he just wanted to get this over with. “I’d be delighted,” he lied. He wrote down her address on a scrap of paper, and before he had a chance to thank her, she had hung up.

Shaw glanced at the address, gave a low whistle. “Swanky,” he said.

* * *

Rhetta Brown sat down to her work much later than was her routine that Friday, which ordinarily would exasperate her, but today as she dropped down into her rattan chair on her patio before her old lap top a definite smirk played around the corners of her mouth.

It’s not like she hadn’t reasons to be irritated.

For starters, Jefferey. It was so like him to let her down when she needed him. She had asked him to march right over to the Lindens’ place next door and get to the bottom of why they had been pointedly not invited to their annual garden party, the crown jewel in the neighborhood calendar.

Last year, she had successfully lobbied for an invite from the skinflint Eunice Linden through a series of persistent notes and the occasional banana bread she sent next door through her emissary husband. It worked. Savoring her victory, on the day she eschewed protocol of being paraded from the front door and through the tedious receiving line like all the others, instead she swept through the gate separating their properties, the privilege of being so near neighbors, and let it drop here and there that she lived just over the fence, she was of the inner circle, here to consume canapes with certain local notables. With Jefferey in tow. After that success, it was imperative that they should go again this year. But the invitation was not renewed.

The Browns lived in the ugliest house on the prettiest street in the tony historic end of town. Theirs was a squat Cape type house, considered a usurper and an eyesore among the sedate Colonials when it was built in the heady post war boom; now Number 217 had the patina of age that gave an aura of respectability suitable to its zip code, but still Rhetta felt the sting of being seen as an outsider. The neighbors never let her forget she’d only been there a few years, whereas they were generations in the same family houses stretching back to before the Revolution. Such snobbery goaded her, spurred her. She’d show them.

Last year at the august garden party, she had the ear of none other than Ellery Wendall, the Editor in Chief of Rex Press, for 15 minutes she had him cornered between the prize winning rose garden and the ice sculpture of some sort of bird in flight, she regaled him about her murders, and her wily detective Sir Archibald Leech, she was on the brink of asking him to read the manuscript she happened to have handy in her bag—well then she could have clobbered Jefferey who chose that exact moment to lope along and see if she needed anything, and of course he should have seen her empty champagne flute and brought over a fresh one, but as she was making this point to him, she somehow lost Mr. Wendall, whom she watched wistfully as he sped away, he must have needed to use the water closet because he moved so fast. No matter. She had marked her prey. She would bag him. In time.

She gave herself an indulgent smile, a blush of hubris that sometimes befalls a genius. An alchemist might understand what’s it’s like to create magic out of nothing. Her manuscript was gaining heft, she’d made substantial revisions since last year—Sir Archibald lived in Monk Stone Priory now, which sounded so much better, and his sidekick with the limp had clearly been damaged in the first war—she knew that her work now at last deserved, no, was destined to be published, read, seen, and most importantly, admired. Wouldn’t that turn a few smug heads. All she needed was just a few minutes more with the editor to make it happen. Those damned Lindens.

Now, as she sat on the patio, her fingers practically ached with the need to produce, the energy inside her was restless, crackling. But still the pesky thought buzzed around: why hadn’t they been invited back? She supposed, in full light of day, that it was probably Jefferey and his blandness that failed to spark. Who wore those skinny ties anymore? Really. She had laid out for him perfectly suitable linen shirt and nice trousers in a soft palette that would complement her outfit which she had chosen with equal care: the dress with the cabbage roses and the silk fringed shawl, stacks of bracelets. She now came to realize that his refusal to wear the approved wardrobe for the Lindens had been the start of disobedient episodes of acting out. Only last month he had declined to speak to the gardener for starting at his work too early, when she needed her rest, and so she had to do it herself, and the man up and quit, so they had no gardener and Jefferey was of course useless in that department. And, just this morning, he told her he was not going to knock on the Lindens’ door and ask them why there was no invitation to this year’s party when everyone had been boasting for weeks about getting theirs. Then, in a kind of showdown, a rare display of assertion which just made him look silly, Jefferey told her he wouldn’t be home for dinner, he had a board meeting, the burden of such a feckless lie made him hang his head like a dog as he hauled his pathetic carcass out the door. She saw right through his nonsense. He’d be singing another tune soon enough, when he learned anew who was in charge.

Then she got that phone call from that odious little man. Peter Kaye. Galling. It was not her fault the other students in class were not at her level. She’d straighten him out too. She thought with a quick glance at her watch she had hours to get something on the page before he showed up. It was the burden of every great artist to forge ahead, to not allow the unseeing critics to get in the way.

Despite all that she had to manage, all the insufferable distractions that kept her from her work, she was pleased with herself. A pitcher of iced tea sat where she’d left it when she went in to answer that call on the house phone from Mr. Kaye, and she felt like she had earned a respite. She poured herself a tall glass, smiling to herself as she thought about her secret. She’d never tell anybody about what she’d done this morning. after Jeffery had left. There might be evidence, if anyone ever thought to look for it. And what would they find, really? A bucket in the tool shed. A few empty bleach bottles. Just the thing to kill prize winning rose bushes. The thought came to her as if heaven sent. Slip in and out the back gate, quick and quiet like a cat. It had been little labor, but oh the rewards. If she was not going to be invited to the garden party, there would be no garden.

The yard only got sun briefly in the late afternoons, the surrounding trees and houses yielded a narrow patch of blue sky that just now blazed bright and hot. She turned her face toward the warmth and sipped her cold tea.

* * *

At the appointed hour, Peter Kaye and Shaw arrived at number 217.

“Jeez,” Shaw said. “Kind of a letdown.” They regarded the unimpressive little white house on a bit of shaggy grass, dwarfed by its grander neighbors. Even though another half hour of sunlight was left of the momentous day the place cowered in permanent shade.

“It’s perfect,” insisted Peter, recalibrating his expectations of Madame Brown. Perhaps she was not as grand as she seemed.

“You sure you’ll be ok?” Shaw said.

Peter resented the patronizing tone. He assured his friend he’d be just fine.

Shaw watched him walk down the gravel drive. He would wait here for moral support, what he wouldn’t give to be there when the skirmish began. Shaw leaned against a fencepost badly in need of paint and tried to make himself comfortable, but he was antsy. Silver leaves overhead tittered, tickled by the unfolding scene.

* * *

A dog started barking. He turned to see an elderly woman and an equally elderly collie making their way towards him.

“Who are you?” the lady demanded. “Why are you lurking about?”

The dog gave another wary bark.

Shaw didn’t think he was lurking exactly. He explained that he was waiting for his friend, who was visiting Mrs. Brown.

The lady’s dry lips scowled. She clearly had no love for the mistress of 217. Was it possible the dog scowled too?

“I understand she’s not very popular.”

The lady gave a dry laugh that brought on a cough. “My sister Martha was the only one in the neighborhood who could stomach Rhetta Brown, but she was always too nice, too unsuspecting.”

“Unsuspecting?” it seemed an odd word to use.

“I don’t trust the woman, it’s as plain as that. Conniving. Makes a fool of herself wherever she goes.” Shaw could sense she was enjoying the chance to trash her neighbor.

“I’ve never even met her. My friend Peter Kaye, he teaches at the Center. Mrs. Brown is one of his students.”

A flash of recognition lit up the woman’s face. “Him I know. My sister Martha. She was a writer. She was forever going on about wonderful Mr. Kaye.” He felt himself rising in her estimation. She even smiled at him. “Rhetta fancies herself a writer too. I see her from my room when she’s out here banging on her keyboard, what a show. Egads. She’d foist her stuff onto poor Martha to read.”

“What does Mrs. Brown write?”

“Drivel. Utter nonsense about English lords killing vicars, or the other way around. Rhetta would drop off one of her famous inedible banana loafs and a pound of paper every so often. Neither was digestible. But Martha, being Martha, she ate the loaf and read the pages, too nice a person to tell Rhetta to shove off.” The woman, suddenly aware that she had been running on with someone she didn’t even know, a stranger, she remembered her manners.

“I’m Patti Andrews,” she said, “I’ll talk anyone’s ear off. My apologies. I forget sometimes how lonely I am these days.”

“Your sister, Martha? She has passed? I’m sorry for your loss.”

“She had a good run,” Patti was not the sentimental type, apparently. “She was 80. Had a bout of a nasty virus that finally did her in. Just a few weeks ago. Such a shame. She was so excited to be in Mr. Kaye’s workshop again, didn’t make it. I do miss her, Rags does too,” she gave the dog a gentle pat on the head.

When Shaw would try to replay the events that happened next, he had trouble making sense of the kaleidoscope of images that refused to form a recognizable pattern. What he remembered as they were talking: the light fading, flowers dropping petals in the sleepy garden, a bird calling to its mate, but the quiet evening ended with a scream ripping the air like a crack of thunder sending the birds scurrying from the trees. Peter screaming Shaw’s name, over and over, echoing in Arthur’s ears, he could see himself moving in slow motion though he must have been running, the crunch of gravel beneath his feet, the dog barking, Patti several paces behind him, the door left ajar as if waiting, the darkness of the house, vague shapes of furniture as he moved toward Peter through a creaking back door to the patio, he flicked on the outdoor light, flooding the scene with a merciless white glare—Rhetta Brown, sprawled out on the gray flagstones in a pool of inky blood. Peter Kaye, trembling, holding in a his hand a heavy stick. A wind shaking the trees a shadow running over tall grass that grew darker and darkeruntil everything went black for Arthur Shaw.

ii

A Murder in Tory Row

The news of the murder rippled through the community as if carried on electric current. By morning, everyone had heard: Rhetta Brown had been brutally clubbed to death, killed by an instructor at the Center. Peter Kaye was in custody.

* * *

Caroline paced Joseph’s studio apartment. He watched her, noting she had barely run a comb through her hair. Her hands were restless, tugging at her long sleeves, fidgety.

“Please. Sit down. Have some coffee. There’s some toast if you would like.”

“How can you think about eating? My stomach is a bag of broken glass.”

“You’ll feel better. Sit.”

She kept walking, up and down the length of the room. The smell of fresh coffee made her insides turn. She swallowed down the sour taste at the back of her throat. “Did it occur to you that we goaded him into it? Did you see his face when he left us in the park? We pushed him.”

Joseph smiled. “I am sure that there has been some misunderstanding. I cannot believe for a minute that Mr. Kaye, our Mr. Kaye, could do such a thing. Have some toast.”

“How can you be so sure? His friend caught him in the act. A neighbor lady too. What further proof do you want?”

“I am sure there is more to the story. We can rationally discuss likely scenarios.”

“Such as?”

“Such as. There may be other people who wished Mrs. Brown dead.”

For a moment she stopped. He had a point. Rhetta was detestable. But there were witnesses. He could not easily explain that away.

“You yourself said you wanted to hit her over the head with her stick,” he sipped his coffee.

She laughed. “So I went over there and clobbered her before Mr. Kaye showed up? She was already dead?” Maybe Caroline fantasized about it, maybe the thought of smacking that woman senseless had crossed her mind once, or a hundred times. She still felt hot when she remembered how unpleasant the dead lady could be, how dismissive she’d been with her critiques in workshop; Caroline was working on a thriller about a heroin dealer who was frantically trying to find whoever was putting fentanyl in his product, killing off some of his best customers, and it was really coming along— Rhetta had been so condescending, calling her antihero “unlikeable.” Duh. That was the entire point. The guy’s a peddler in class A substances. He wasn’t meant to be likeable. But you couldn’t have a conversation with Mrs. Brown. She called the whole thing “unsavory,” and something “no decent person would ever want to read.” Pretty brutal. It would be completely different if Rhetta herself was this amazing writer, but she wasn’t. Who the hell wants to read about English folks politely killing each other, bloodless murders with no visceral juice, no passion. No life. She had thought about it. Clocking the insufferable she beast with that stupid stick. “Do you think I could have done something like that?” she asked her friend.

“I am saying that someone could have. As you say, she may have been dead before Mr. Kaye even got there. No one actually saw Mr. Kaye strike the woman. You told me yourself that he was standing over the body with the stick in his hand, but does that necessarily mean he killed her? There may be other details we are not yet privy to.”

She hugged herself.

“The coffee is still hot. Sit.”

“What are we gonna do?”

“We are writers. Mystery writers. Maybe we find out who really did it?”

“Like Nancy Drew? Skulking around for clues in old clocks?”

“We can be more methodical, perhaps.”

Caroline was intrigued. “You think we can?”

He lifted his shoulders. “It cannot hurt to try. It may even be fun.”

“I’m calling June,” she said, pulling her phone from her back pocket, “she’ll want to be in on this.”

* * *

Arthur Shaw had not slept. His head still ached. In the bathroom mirror he touched the still tender line of stitches on his forehead, replaying the ambulance ride to the Emergency Room, the kind paramedic who told him he was lucky. He had passed out, fell to the ground, taking with him a small table and sending a glass pitcher shattering on the flagstones. One of the shards just missed his left eye. He was lucky.

As he was being taken away to go to the hospital, flat on his back on a stretcher, he saw the moonless night, the black sky. Blue lights flashing. Red lights flashing. Neighbors gawking on their lawns.

But it always came back to the same image, burnt into his brain.

Peter standing over the dead woman’s body.

Arthur heaved over the sink, nothing but green bile from his empty stomach hurled into the white basin, the clockwise swirl of the taps and vomit spiraling around the drain made him hold on to the edge of the vanity for dear life.

* * *

Jeffery Brown instinctively put the key in his own front door with the stealth of a thief, quietly, holding the knob steady in his hand while the lock opened, then nudging the door with his shoulder, listening, his ears attuned, attentive. The furniture regarded him with stoic silence. Early American couches. Shaker chairs, ladder backed, spindly legs that would give way if anyone dared sit on one, but no one ever had. The entire house felt inert. Hollow. Dead. And then he remembered. There was no need to sneak into his home for fear of making noise, afraid of ruining a nap or a writing spree. There was no exasperated sigh when he did make himself known by tossing his keys into the painted bowl on the hall table, just the bright clinking of metal on porcelain. He could yell at the top of his lungs if he felt like it. But he didn’t. Funny. Twenty plus years of tiptoeing so as not to disturb the Chippendale dining chairs that stood as mute guardians around the oval table with its centerpiece of wax fruit. The wallpaper, sly sheperdesses leading willing shepherds away from their flocks in an endless repetition always made him dizzy, and he automatically went straight for the kitchen.

Rhetta had shown an indifferent talent for cooking. She made a big show of burning cookies and loaves heavy as bricks, she could do a roast drier than death or incinerate a chicken with equal poise, but she excelled at leaving behind a mess. The counter still had a shriveled half lemon sliced on the cutting board. Granules of sugar all over the place inviting a parade of ants he brushed into the sink full of plates and glasses smeared with orange lipstick.

The back gate unlatched.

Then the familiar sound of heels clicking on the flagstones.

When the footsteps stopped abruptly, breaking the characteristic confident stride, for a beat there was just stillness, not even a hint of a breeze came through the open window where he stood watching her. She shouldn’t have come. Not now.

Eunice Linden stood still, her peep toed shoes inches away from the black sticky stain of dried blood, broken glass, the table on its side where Rhetta had been lying just twelve hours ago. He saw the effort it took her, to suppress a scream, compose her face, but underneath he was sure she was now afraid. Afraid of him.

She gingerly stepped around the stain, the glass, the table. “I saw your car. Are you Ok? Jeff, I couldn’t sleep thinking. What did the police say?”

“Come in,” he said. “Might as well make me a cup of coffee while you’re here,” he held open the screen door, the creak of the old wood frame reminded her of Thursday afternoons. Despite herself, she smiled, remembering, but the moment she heard the door bang shut behind her she knew it was wrong to come, today, but she had to see how he was. She had to know. He supposed she had a right to know.

Eunice busied herself in the kitchen. Measured out coffee, filled the carafe from the tap, remembering to let it run until it was cold. The whole time his eyes were on her.

“I told them I had an alibi.”

She pulled two mugs off their little hooks. “What did you say?”

“Same as I told her. Board meeting.”

“But they’ll figure it out soon enough. Jeff—” she turned to face him, “why did you lie? Can’t you get in trouble?”

“I thought I was being chivalrous,” he touched her forearm, noted the split second when she wanted to flinch but didn’t. Her eyes looked everywhere but at him. “It’ll get out. There’s no avoiding it now. I bought us a little time” he said.

“I guess so,” she was tearing up, scared, a little girl with a manicure and hair that smelled like money. “What a mess.”

“Wipe your nose.”

“Jeff. You know I’m only going to ask you this once. I swear I’ll never mention it again. Whatever you say.” She tapped two big spoons of sugar into his mug. A Splenda in hers. “Did you have anything to do with it? You didn’t do anything because of–”

“Did you?”

She winced as if he had slapped her. “How could you even ask me such a thing?”

“How could you ask me?”

“I’m sorry. I’ve been a wreck. Crazy things are going through my mind.”

“We’re going to have to decide. If this thing is going to be between us, or if—”

“Or if—”

“Or if, regardless of what comes out,” he held her by the wrist, “we’re in it together.”

“How? Can we trust each other?” There was a deeper question she did not dare ask.

“The coffee. It’ll go a lot faster if you tap that little button. There.”

* * *

June had to knock a few times before Shaw got up to answer. He had finally drifted off to a kind of sleep, peppered with terrible dreams.

“You look awful,” June said.

“Thank you,” Shaw’s glasses were nowhere to be found. He squinted at his unexpected visitor. “I’m sorry. You are—”

“June. You know me. I’ve met you lots of times,” she seemed to know what she was talking about as she stood there with her hands clasped in front of her, reminding him of a reading teacher he had at Park Glen Elementary. She did look familiar. Fireplug build. Sturdy. Eyes that looked right at you. “I met you at Mr. Kaye’s parties for the Center. You have to remember.”

“Of course,” he lied. “I’m so bad with names though—”

“June. June Jablonski.”

“Hello June.”

“I know this is a bad day. We’re all worried sick about Mr. Kaye. We know of course he didn’t have anything to do with it. Imagine. Impossible!” she looked at his stitches, “Oh dear you got your share of it too, I’m so sorry. You must be devastated. About Mr. Kaye I mean.”

“I don’t know what to think yet. I don’t. I can’t—”

“I understand. We all feel the same way.”

“We all?”

“Mr. Kaye’s workshop. At the Center. That’s us.”

Things started clicking into place. Yes. June Jablonski. “Thank you. I appreciate it. Thank you so much for coming by—”

“Mr. Shaw,” said June, “you misunderstand me. I didn’t look you up just to offer our support, which you have, obviously. We’ve been talking and we think we can dig around and maybe find out somethings about the whole business with Rhetta. If Mr. Kaye didn’t do it, and he didn’t, then we need to find out who did.”

He and Peter had enough murders. He was tired. This wasn’t a game or some episode of Midsomer. There were real consequences. “I don’t think that’s wise,” he said.

“I’m disappointed in you, Mr. Arthur Shaw.” Now she really did look like Mrs. Pennell from Park Glen. She was frequently disappointed too.

* * *

Caroline and Joseph had a fruitless morning. She was frustrated, but he was as steady as ever.

Of course, they tried the police station first thing, but some desk guy told them no way were they getting in to talk to, much less see, Mr. Kaye, and he’d give no information on an ongoing investigation.

“May we leave a note?” asked Joseph, and honestly it seemed perfectly reasonable, but the guy was not having it.

“Maybe tell him we said hi, even?” She had asked, knowing it was a doomed effort, but she had to try.

They were out on the pavement beating it back to the car within 8 minutes.

“Now what?” she said as she buckled into the driver’s seat. She hoped her voice didn’t have the irritation she felt. So far, he seemed undaunted by her cynicism, a carryover from an embarrassingly long Emo phase, when she was one of a million standard issue bar rats with a burgeoning eating disorder centered around vodka and clove cigarettes, a fuck everyone attitude, and a knack for finding the worst, the absolute worst guy in any given situation. She was getting incrementally better now, trying, but that pessimism lingered, a smudge of black eyeliner on a hangover morning with your shoes still on from the night before. Caroline admired Joseph, his sense of inner quiet that she could only wish she felt for maybe fifteen consecutive minutes in a month. He remained placid and smiling all the time. And it wasn’t an act. You can tell. He was also her best friend in workshop. She gave him a smile, hoping to soften her tone.

Of course, he smiled back. “We made a valid first attempt,” he said.

Which is a nice way of saying they struck out.

* * *

Patti Andrews didn’t answer the door bell when June and Shaw rang.

“Why exactly are we here?” asked Shaw. He had been led around by this tank of a lady, succumbing to her natural role to lead, and his to follow. In the absence of Peter, he was feeling the loss of someone telling him what to do, maybe that’s why he allowed June Jablonski to push him through this sleepwalking day. None of it felt real. Only the stinging itch over his eye told him different. He had no idea why they should be standing under the portico of the Andrews’ house.

“I explained on the way over” June’s voice again had that irritated edge of someone who doesn’t like having to repeat themselves more than once. “You and Patti were there last night. You saw what you saw. If we get the two of to talking, maybe some interesting details will emerge.”

“I told you all I remember,” he said, exasperated with himself.

“Listen, this might jostle the old memory, kick it into gear. Patti might have seen something, heard something that you didn’t. Visa versa. Something we can piece together. Can’t hurt. Give it the old Harvard try.”

“Did you go to Harvard?”

“Radcliffe, dear. That’s where I met Martha. And hence Patti. We’re all friends going way back.”

“Martha? The sister who died?’

“She was a wonderful gal. I was so pleased she said she was going to be in this year’s workshop, with Mr. Kaye. Terrific writer. She died just a week before the first class met. Poor Patti. All alone in this big old house. So you see, I owe her a visit anyway, check in on her, see how she’s doing. Martha was the lovingest, kindest person you’d ever want for a friend—”

Shaw remembered how Patti had described her sister: “Unsuspecting.” It seemed to be an unusual word at the time, and it still stuck out.

Just then Patti Andrews turned the corner, a shovel in her hand, ratty jeans caked with dirt. “Heard you ringing,” she said, “persistent, aren’t you?”

June laughed. “Patti. Forgive the intrusion. I felt I was long overdue in paying you a condolence call.”

“I got your card, that was very thoughtful.” Patti attempted a smile, “We didn’t do anything. Why give that kind of money to the funeral parlor? She didn’t believe in all that. Just wanted to be cremated and that’s it.” And then she recognized Shaw. “You I remember,” she said. “Nasty gash you got there. Hope you’re OK.”

OK was as much as Shaw could be. He nodded. Mumbled thanks.

“Patti, dear, we were hoping that you might be willing to talk a little bit. About last night.”

“All talked out. Those cops are something. I thought you were them when I heard you out here,” she held the shovel as if it might have been brandished, in the event she needed to shoo off a detective or two from her doorstep. “Besides. It was that fat fella. He was standing right there, holding the damned stick in his hand like a club. Doesn’t take a Miss Marple to put that together.”

Shaw winced. He too had been asked, over and over, even in the Emergency Room while they were stitching him up. He was exhausted. There was no way to unsee what he had seen. He didn’t want to talk about it, either.

June tried a different tach. “Martha was quite fond of Mr. Kaye.”

Patti nodded. That she was. Loved him. She was looking forward to being at the Center again.

“You might as well know that we don’t believe that Mr. Kaye could have had anything to do with something like this. There’s got to be another way to look at this. We need your help. Please, just let’s walk through it. Once more?”

Patti knew full well that June was not going to give up, she was a squirrel with a nut. “Fine.” To Shaw she said, “I didn’t intend any offense. Of your friend I mean.”

She led them to the garage that had once been a stable, its barn like doors open, she invited them to sit on a couple beat up plastic lawn chairs while she finished doing the things she needed to do. “Got to keep my hands busy. Since Martha. I’m just talking to myself and trying to stay occupied. You won’t mind?”

They didn’t.

She put the shovel up on the wal. Everything in its place.

An ancient car took up the middle of the interior, a hunk of curvy metal, wide white wall tires, a steering wheel you could crack a tooth on, solid. It was bathed in a light worthy of an operating room that made the hood ornament, a winged woman in flight, gleam in blinding glory. Patti picked up a chamois rag to rub the chrome bumper and grille with all the attention of a loving parent.

“That’s a 1955 Nash Rambler Cross Country wagon,” June said to Shaw, knowingly. “Six-cylinder.”

“Ugly. Isn’t she?” Patti continued buffing. The metal shone mirror bright. “She really did go cross country. Twice. Might be able to do it again. I wouldn’t be surprised.” She patted the car like it was a horse, or a dog, an old friend that has served well. “Of course, for every day, I putter around in the Civic,” she gave the other car a look that said it was no comparison.

The shelves were organized. Shaw read the names of the metal cans and jugs, names that remined him of his dad: Motorola. Valvoline. Carnauba Wax. Penzoil. He half listened as Patti went through the events of last night, answering June’s questions, the same things he’d gone over and over so often he could recite them like a litany, ending with the two of them there on the patio, but something, something he had almost forgotten. “Ms. Andrews, do you remember? Last night? Did you hear anything like footsteps? Like someone running across the lawn? There was a shadow or something?”

She paused and considered, rag still in hand. “Hmmm. Now that you bring it to mind. I think that’s right. I think so.”

June clapped her hands. “There. Now we’re getting somewhere. Someone could have been there. Someone else! It’s at least a possibility.”

“It was confusing,” Shaw said. “I thought I imagined it, there was so much to take in, and the dog barking—”

“Dog barking? Where is old Rags, anyway?” asked June, wary, she did not like dogs as a rule, they were always sniffing where they shouldn’t.

No answer.

“She’s usually glued to your hip.”

“That she was.”

“Patti, dear? Are you OK?”

Patti leaned against the hood of the wagon and for a moment it looked like she was about to cry, something so strange on that stoic granite face. Shaw and June exchanged a concerned glance, and then at the shovel hanging on the wall still coated with dirt.

“Stupid thing,” she rubbed her eyes with the back of her hand, “must’ve gotten into something last night in the middle of everything else. You know how dogs are.”

Shaw had never been so happy to see the Rose Hill Apartment Building, every cell in his body felt fried, in need of sleep. He waved as June zipped off in her sturdy Subaru, but he didn’t know if he had the energy to walk the dozen or so steps from the curb. Only the promise of bed prodded his body forward. He couldn’t think, didn’t want to think. The whole thing with Patti was—he couldn’t come up with the word—it didn’t matter, except that maybe she’d heard it too, that someone else was there in Rhetta’s backyard last night, maybe it wasn’t Peter. He desperately needed to believe that.

At the door his nose wrinkled with the distinct yellow tang of cigarette smoke. Unmistakable. Now he was having sensory hallucinations, Shaw worried, his years in nursing told him this was the first sign of cognitive slippage, it was happening, dementia was creeping over him, this was the beginning of the long gray twilight. Dotage. Old Timer’s, his mom had called it, before she wandered away further and further, and suddenly forever gone. His odds of it were just that much higher, this much was simple science and genetics, and it scared him to death to think about. The more rational part of his brain interjected that he was just as likely suffering from sleep deprivation, and the incredible stress of current events. Sleep. That’s what he needed.

Something else though.

The apartment wasn’t empty.

Someone was inside.

Someone was here.

This was no blip in mentation, he was positive. He didn’t think a burglar would take a smoke break in the middle of a heist, but what did he know about burglars? Next to nothing. He grabbed an umbrella from its stand, he needed something, anything, he might use to defend himself. From the narrow hall he barreled into the living room, brandishing his weapon in front of him.

“Is it raining indoors?” Peter Kaye said from the usual armchair he assumed whenever he visited. Peter Kaye sat there with that infuriating smirk, smoke curling around his round face. Peter Kaye was sitting and smoking and smirking.

“You know I hate it when you smoke,” was the first thing Shaw said. And then he collapsed on his couch. “Am I dreaming? Did I finally snap? What—”

“I used my key. I hope you don’t mind. I wanted to call you, but then I thought a surprise might be more fun.”

* * *

Caroline and Joseph came up craps, again.

Back to the car.

Caroline needed a fucking drink.

Her passenger didn’t say a word when she pulled in front of the Abbey. “Let me buy you an Aperol Spritz.” She said. He liked the sweet stuff. Her drink these days was something hard and brown that burned and did the job quick. “I’m beat. Chasing a murderer is thirsty work. What do you say?”

“We are not quitting,” he said.

“No. Just a teeny tiny little break.

“Just one?” he asked.

“Sure. Yeah. Let’s go.

He gave her the stern eye.

“I promise,” she said. “One.”

They were deep into their second round. Joseph was starting to droop, but Caroline was bright as a field of daisies. The frustration of the day evaporated, and in its place a warmth flowed through her, made her giggle.

“What is so funny?” Joseph looked up from his notebook, he was starting a list of suspects. He felt their investigation up until now had lacked vision. He wanted to recap.

“You. You and your lists. You and your spreadsheets.”

There are two kinds of writers, it is said: “plotters” who outline and work out the mechanics of their stories; and “pansters,” so called because they fly by the seat of their pants, guided by inspiration and intuitive processes only understood by themselves. Joseph, no surprise, was the former. His notebooks were full of meticulous, detailed narrative elements. Character biographies, backstories, motivations, plot points all written out in his neat block writing. She knew him to be a Virgo, so there you go. Fastidious. Always kempt. Tidy. Shirts ironed and buttoned up. Caroline had her own kind of system involving random post it notes, crumpled napkins with scribbles she’d find in her pockets, her phone rife with cryptic notations. As to dress, she drew from a pile of cleanish laundry that lived and died on her bedroom floor.

“Having a method is not a bad thing,” he said, his breath thick with Aperol. “Especially now, if we are hoping to solve this. Will you help me, or not?”

She drained her bourbon and signaled the bartender for another round, ignoring Joseph’s well-groomed raised eyebrow. “Fine.”

“Mr. Kaye is the first suspect, but we agree he could not have done it.”

“Check.”

“Sylvia, Debra, also have very strong alibis which eliminates them.”

They had hiked down to Sylvia’s who predictably had nothing to say. Sylvia Berry was the one person in workshop who never offered a word of useful critique other than she liked something, or she didn’t like it. The worst. Pretty meek as a writer, wouldn’t venture out of safe tropes and cozy mysteries neatly pieced together. She didn’t kill Rhetta. She was in Providence overnight seeing her sister recovering after hip surgery, just got back on the Acela which might make an interesting place for a killing, she told them. Murder on the Boston Express. Very original.

It wasn’t Sylvia.

Ditto Debra. They went to see her, or they tried to, but she was down after testing positive yesterday and it was clear she hadn’t moved from her bed in the last 24 hours.

“Check and check,” Caroline confirmed.

“Then there is ourselves.”

“It just got interesting,” she laughed.

“Be serious, for one time” but he was laughing too. “Let us do this properly.”

“So, where were you last night?” she poked him in the chest. She sometimes got a little handsy when she drank. She watched as he added his own name to the list, each letter exactly of the same proportion, so neat and orderly, which might be a red flag. Who knows what sociopathy this signaled?

JOSEPH

He put down his pen, parallel to the pad, and smiled. “I was entertaining a guest,” he said, the closest he’d ever gotten to saying anything regarding what he always termed his “personal life.” He would sit through any of her stories about the parade of sad sacks who lumbered in and out of her “personal life,” but was as a rule absolutely mum about himself.

She had begun to think he was a prude, or some kind of monk, and now she looked at him with renewed appreciation. “You dirty bird,” she said. “Tell me every detail.”

He shook his head. “Suffice it to say I can produce receipts, if necessary.”

“No fair. I tell you everything.”

“Yes. You do.”

“Well!” she gasped like a daytime TV diva, making them both hoot.

“Now, what about you?”

“What about me?”

“Where were you last night?” He wrote her name on the list.

CAROLINE

She took a healthy swig of her fresh drink, felt it warming her gullet. There was no answer to his question.

“No. Again?” he asked.

Her hand gripped the heavy glass.

“Again?”

“The sun went out,” she said, “I don’t remember after that. But I’m sure I didn’t have the wherewithal to kill anybody.

“Besides perhaps yourself.”

She sucked down her drink.

“Merde.”

“You can cross me off your little roster. I was blissfully comatose.”

“Why, though? You were doing better–“

“Not having this conversation,” she said, “stick to your list.”

He gave her that look she was dreading. He really did have beautiful eyes, but they could be uncomfortably steady when they looked at you in that way. She knew he wouldn’t think any less of her than she felt herself. If only he wouldn’t look at her with such intensity. It was too much.

She said: “I’m sorry.” The two words were puny, insignificant. Meaningless. But not to him. To him, to Joseph, she meant it. Every time.

Eventually, he nodded, and ran his hand over the page, smoothing it down, laying it flat. He picked up his pen, added a name to the list.

MR. BROWN

“The husband,” he said.

“Why him?” she breathed again, relief crawled its way back into her belly to have his attention move on from herself.

“It may be cliché,” he said, “but it is often the husband who does the killing.”

“Imagine being married to Rhetta Brown,” she said, and they both laughed again, but it was just a little less bright. A little less happy. And they did not look each other in the eye.

Eunice Linden regarded her hands which still held onto the steering wheel even though she had been parked in the lot of the police station for ten minutes. She had rather good hands. She took care of them, of course. Lots of creams. And those well-tipped girls at the nail salon. No age spots. No spreading of the joints other women her age had, those athletic Smith gals who were always playing tennis and golf. She’d never had to have her rings re-sized, like Helen Forest had to do.

Her rings.

The five carat marquise cut engagement rock, its matching platinum band of diamonds.

A significant sapphire sparkled on her right ring finger, an anniversary gift from Chip. That one she slipped on just before she left the house. She needed a talisman, something to remind her if she should again waver from her express purpose:

There was just no way she was going to leave her life and all it bought, to be with someone who couldn’t afford her.

If she were to appraise the worth of herself, right this minute, the bracelets, the earrings, the bespoke bag and shoes and soft knit jersey silk wrap dress, the hours spent on hair and makeup and training sessions, if she added up all that it cost to be her, she’d have to admit that she was an expensive lady, and that sum would be something quite northward of what Jeff Brown could ever hope to have. She did not feel the least bit mercenary. One has to look at things rationally, with cold logic and reason.

Maybe her joie de vivre had gotten in the way briefly, but it was foolhardy to be guided by a passing flame. Jeffery remained the front runner among suspects in Rhetta’s death by virtue of being a husband in love with someone else. Poor Jeff. He had been so susceptible, letting his ardor reach the inconvenient sticky stage. She had cared for him, in her way, but the itch was scratched. This current situation might be an expedient full stop to their dalliance, as fun as it was.

There was plenty of evidence she could give. He had told her how much he hated Rhetta, how much he wanted to be free of her, how she kept him like a pet dog; Eunice Linden could say any number of things. With one last look at herself in the rearview she checked her lipstick and ran one of those lovely hands through her hair. She practiced looking sincere. Eyes clear. Gaze steady. Time to tell her story.

* * *

“Did you escape?” Shaw could not imagine his friend overpowering a precinct of police, but he had never imagined that he might be capable of killing anyone either.

Peter laughed with his whole body, from his belly. “Oh I do love you, Arthur Shaw. I needed that,” he was still laughing, “it been quite an unusual day.”

Shaw nodded. It certainly had been. “You didn’t—-?”

“Of course I didn’t,” Peter stubbed out his cigarette on a tea saucer he was using as a makeshift ashtray. “Frankly, I don’t know whether to be flattered or insulted. A point we can re-visit another time over a cocktail. You’ve known me longer than anyone. Did you really wonder?” Peter was clearly enjoying the situation, his friend’s confusion, the very idea that he might have—

“Then what did happen? How are you here?”

“It became apparent to the police that I wasn’t their man. At least they don’t jump to conclusions without evidence.”

“What evidence?”

“Well, the good lady did not die from being bludgeoned. There was no indication of that kind of blunt force trauma at all. She was dead hours before we even got there. The medical examiner on the scene said something about her esophagus being burned. They don’t know yet what poison it was, but it did the trick effectively.”

“But all that blood, the stick—”

“Think about it: she ingests poison, at some point when she feels the effects she jumps up,” and here Peter clutched at his throat in dramatic replay of the way he saw it happen, “She teeters, she falls or trips. Hits her head bang on the hard stones. You know how head injuries bleed like hell.”

Shaw nodded. That was true.

“I have to say, I feel sorry for her. Such a terrible way to die. Brutal. Someone had to have really hated her. It’s sad to contemplate.”

“I had this image of you in my head. It was. I—”

“From the very beginning that stupid stick was just a prop. Picking it up, well that was sheer stupidity on my part. I don’t know what I was thinking. I must have looked like a villain when you came on the scene,” he laughed again but when he saw the look of anguish on his friend’s face, he got more serious. “I’m sorry Arthur. That you had to go through that. Look at you. I’ve never seen you so hangdog before. I will admit that scar you’ll have will be very butch, but that too is another conversation for another day. You’re exhausted. It’s OK now, I’m here. It’s going to be fine.”

All Shaw could do was nod. Verbal ability was flown away as the irresistible desire to close his eyes came over him.

“I’m happy to see you, Arthur. But it’s time you went to bed. We’ve all had a long day. There’s plenty of time to compare notes.”

Shaw’s outstretched body had already gone slack, his mouth open wide.

Peter, all tenderness and care, covered Arthur with a throw.

“You’re not going away again?” Shaw mumbled, emerging for a moment from the soft fog.

“I’m not going anywhere,” Peter soothed, “I’ll be sitting right here with a book while you rest.”

Shaw smiled. “I want–” but he forgot what he wanted as he slipped mercifully, finally, into the depths of sleep.

iii

A Death in the Afternoon

“Poison?!” June Jablonski said. “Poison? This changes everything!” She was sitting with Peter Kaye and a refreshed looking Arthur Shaw on a bench in the Commons. A nearby playground full of children gave the scene a more sinister feel, as though a conversation about a deed so dark amid such innocent noisy happiness was subversive, and she had made a conscious note to lower her voice, but still, she couldn’t hold back her utter surprise at the turn of events. The most important thing, obviously, was that Peter Kaye was free, safe from harm. She knew all along he wasn’t guilty of murder. She kept touching his arm to make sure he was real, and this was all really happening. He was, and it was. The new facts of the case were that Rhetta had been killed by poisoning, and the state of the body indicated she had been dead at least two hours before she was discovered on the patio. “This opens up a whole new set of possibilities,” she said.

Peter Kaye nodded. He felt the sun warm on his skin, the breeze, he heard the kids laughing at play, and allowed himself a smile of simple gratitude to be back in the little park again. “It certainly clarifies the timeline of the crime,” he said.

“You were on the phone with Rhetta at one o’clock, and we showed up there at 7 sharp,” said Shaw, “it happened sometime between one and five pm, if the coroner’s time of death is accurate.”

“So, what was the poison? How did it get into her?” June’s mind spun scenarios, but nothing clicked yet.

“It’ll be some weeks before the medical examiner will confirm, but from the preliminary observation it was caustic enough to burn her esophagus, that may narrow the field,” said Peter.

“Maybe ethylene glycol,” guessed Shaw, who had seen his share of poisonings in his years when he worked the emergency room. Gruesome. Inventive solutions for offing friends and loved ones. Mundane things used for murder.

“Ethylene glycol?” June asked, again trying to keep her voice down.

“It’s the chief ingredient in antifreeze,” Shaw said.

“Antifreeze. Anybody can get a hold of that. But how could they get her to drink it?” June felt that Rhetta was too smart to fall for a cheap trick.

“It reportedly has a very sweet taste,” said Shaw, “you might not notice it, It would depend on the dose, how much was ingested, before you felt its effects”

Peter shuddered. “How awful. The poor woman.”

They all sat quietly with the image of Rhetta’s last painful moments. No one deserved that.

Shaw broke the silence with a sudden memory of the shattered glass, reflexively he touched the area above his eye, “There was a pitcher,” he said, “the table. I knocked them over. The pitcher had something in it, something she was probably drinking. Someone could have put antifreeze in that.”

“That makes sense,” acknowledged Peter, “but I’m curious as to when. Assuming she was sitting on the patio, drinking something—”

“It was a warm day,” June interrupted, “maybe it was lemonade. Or iced tea.”

Peter gave her the briefest look that suggested the beverage itself was immaterial save as a conveyance for whatever agent that killed Rhetta. “I was going to interject the question: when might someone have slipped in poison without her knowing?”

“Perhaps she had to use the bathroom, or got up to make a snack?” June said, undaunted by askant looks from such an old dear as Mr. Kaye.

“Or she was called away,” said Shaw.

“I called her,” Peter said. “I called her at one o’clock, like you said Arthur, she went inside to answer the phone—”

“And someone with a jug of antifreeze came along?” June laughed, it seemed a little far-fetched someone would have been practically lying in wait, watching, waiting for a window of opportunity. Why? And more importantly, who?

* * *

Jeffery Brown nursed his coffee while he did the dishes in the sink, set the kitchen back to rights. He stepped out onto the patio where he swept up glass, returned the wicker table to its corner. The police had collected all they needed, and now there was nothing left to do but what he had always done, clean up a mess.

For 10 minutes he blasted the hose on the flat stones, sending a black cloud of flies swarming off to hover nearby in wait only to swoop back in for another taste, constantly dodging the spray of water. It was no use. The blood had seeped into the porous surface. He shut off the spigot, took his time coiling the hose into a neat arrangement, took his time while he waited for the police to show up. Any minute, he expected to hear a knock at the door. His head ached. His stomach burned with acid and bitter coffee on an empty stomach.

He had watched Eunice walking away this morning through the back gate like she couldn’t get out of there fast enough. He didn’t call her back. Probably because he knew it was no use. When he saw her backing her E-350 out of her driveway and speeding off, he knew she was running to the cops to tell all about their affair, his lies, his motives for killing Rhetta.

Ironically, it was Rhetta’s doing that started the whole thing. She kept sending him next door to the Lindens with little notes and block-like banana breads begging for invitations to this and that, and after a while Eunice began to think Jeffery was a man who needed a little bringing out. Like one of her prize roses, he might do with a bit of pruning and coaxing into full flower. He just wanted a little attention. Eunice Linden was a very good gardener. Under Eunice’s husbandry he did bloom. For one brief Spring he had reached toward sunlight, felt something as close to love as he’d ever expected to find. He blossomed.

Rhetta couldn’t keep a cactus alive.

He had lived as her husband for two decades, slept in bed next to her for 7,300 nights, give or take. And now, in her absence, now that she was gone, just gone, like that, he honestly didn’t know how to feel besides an unexpected sense of relief. He was of that generation of men whose emotional interior had been stripped bare since boyhood, who found themselves at some points in their lives troubled by an emptiness that had no shape and no description. What saddened him now was that he didn’t feel sad, hadn’t cried, hadn’t wanted to think too deeply about any of it and so kept himself busy, yet there was this pesky vague idea that he should feel something, and he puzzled this out as he walked back into the darkened house.

As a young man, he considered going into the seminary, not because he had any deep faith in anything, but because he was searching for an answer to that well of hollowness he felt. When he met Rhetta, her overbrimming confidence and unquestioning sense of forward directed movement intrigued him. If he lacked a sense of purpose, Rhetta blazed ahead, and he found himself swept up in her orbit like a mote of dust in the tail of a comet. He came crashing back to earth soon enough. And now she was gone.

Eunice too. He allowed himself to think that maybe what they had would be for keeps, but it ended with the snick of the back gate latch when she left an hour ago. He saw his own folly. Too late.

In one day, he had lost two women.

It seemed unfair.

A leaden exhaustion came over him. He needed to wake up. Needed some clarity. Needed this pounding headache to go away. Jeffery noticed the little red light on the coffee maker still on. Despite nausea bubbling his insides, he poured the last of it into his mug, sweetened it up, sat back down at the kitchen table to think.

The house was quiet.

And cold.

The minutes ticked away on the wall clock. He swallowed down coffee, watched the minute hand sweeping around and around which made him dizzy and sick.

Coldness gripped his insides, colder and colder as he stumbled upstairs with heavy feet, a hand on the banister. His head throbbed with the racket the birds were making in the trees just outside the window. Sheer curtains muted the sunlight but still he flinched at the blazing whiteness of the bedsheets looming a few steps ahead. He didn’t take off his shoes. Rhetta would be furious with him he thought, as he crashed flat on his face.

Birds kept roaring, screaming in the treetops. But he didn’t hear a thing.

* * *

Caroline watched Joseph make his way to his building’s entrance after she dropped him off, it’s the thing you do, you wait to make sure a person is safely delivered. He, as usual, turned and waved with his keys in his hands, he smiled, and went in. He acted no differently than he had on a hundred other afternoons, was just as serene and kind and thoughtful as always, and this for some reason felt even worse. If he yelled. Screamed. If he could, just once, show he was really angry. She understood anger. But this, this unyielding kindness made her feel more like a shit heel than any throw down combat ever could. She could defend herself against anger. She learned how. The difference here was that Joseph cared, really cared, about her, about what happened to her, whether she lived or died, and she could not just toss her life away like it didn’t matter anymore, couldn’t piss it away with drinking and pill popping and a lineup of loser guys without feeling like she was somehow hurting him.

When her phone rang it startled her, she wiped at her eyes with the long sleeve of her shirt and took a deep breath.

June.

“Caroline. I’m sitting here with Mr. Kaye. He didn’t do it. You were right. He’s free. He’s sitting right here, can you believe it?”

Now she let the tears come. “What happened? Is he OK?”

“He’s fine, he’ll tell you all about it himself tonight, we’re all invited to his place for dinner tonight, and he’ll tell us everything. I just wanted you and Joseph to know, so you can keep looking for the real killer,” June laughed, as if it was some game like a scavenger hunt. “But get this—Rhetta was poisoned. We think someone slipped antifreeze into her iced tea. Isn’t that horrible?”

“Antifreeze? In her tea? Who?”

“That’s just it, dear. Who, indeed?”

“Can I talk to him?”

“Certainly, dear—” and then June Jablonski disconnected the call, probably by hitting the wrong stupid button.

God damn.

Caroline went to hit redial when something Joseph had said occurred to her. The husband. Cliché or not, he did have the easiest access to Rhetta of anyone to poison her.

Caroline had devoured true crime podcasts, watched Netflix plenty enough to support the theory of murderous marriages. An idea buzzed in her brain, persistent through the fog until it started to be clear that she could break this thing, she could go right over there and knock on the door and get Mr. Brown to confess. She could go right now and talk to the guy.

She rummaged in the glove box, pulled out nips of Fire Ball she kept for just such an occasion when she needed a jolt of confidence, had already downed one in the time it took to punch an address into a GPS and was working on its sibling when she did a U-turn on Mass Ave to head back in the opposite direction.

* * *

Shaw and June were filling in Peter Kaye about the events of their morning.

“Patti Andrews confirmed she also heard someone out there in the backyard. I knew it had to be someone else, obviously, but when she said that it was the first full breath I took all day.”

Shaw nodded, but then thought about it,” That doesn’t really make sense though. I mean, now that we know Rhetta was likely dead by 5 p.m. or so, why would the killer have just hung around the back yard for two hours?”

“I don’t pretend to understand the mind of a psychopath, Mr. Shaw,” for clearly whoever had done the act had to have been crazy. That seemed obvious.

Peter Kaye wondered, too: “I don’t know if I agree our killer is someone deranged at all. It would have taken someone of great patience to wait out the right moment of opportunity, assuming that her drink had been poisoned, that speaks to a certain amount of pre-thought, premeditation, someone who had thought about it and seized the moment when it presented itself.”

“Don’t you have to be a little off the nut to kill someone? Doesn’t that stand to simple reason?” June didn’t like the idea a cold-blooded killer. She wanted there to be a certain amount of passion. When they’d all thought Rhetta had been clubbed to death, that made sense, it was an act of the moment, rage, fury, that appealed to her in a killer, someone pushed to the brink of insanity to do such a terrible thing.

“What if they felt they were justified in the murder of Rhetta Brown? What if they felt she somehow deserved it?” Shaw asked.

“That would still be crazy,” insisted June, “what on earth could justify murder? Even of someone as universally unlikeable as that woman?” She had to wonder what Rhetta could possibly have done to get herself killed. There had to be a why.

Peter was willing to concede that under the ordinary definition of “crazy” someone had acted in an abhorrent manner, that was clear, but whatever motive they’d had, whatever rationale they had formed to do the thing itself, it seemed logical and reasonable to them, and he went down this esoteric path, pedantically explaining the underpinnings of subjective morality, to which June replied:

“Nuts.”

* * *

Patti Andrews heard the mail truck pull away. Probably just the bills, she figured as she wiped her hands on a clean cloth and looked in the mailbox. Writers’ magazines still came for Martha, and she just let them pile up, couldn’t haul them out with the recycling, not out of any sentimentality but from the habit of many years living with someone. Every few weeks another one came, and Patti added it to the pile by Martha’s reading chair, same as always. No bills today. No magazines. A store flyer with this week’s specials and coupons. A postcard advertising a local window cleaner and sons. And a large white envelope stamped by the office of the City Coroner and Medical Examiner.

After all these weeks of waiting.

She needed to steady her hand so she could open it, she wasn’t going to wait until she got inside or sat down, she tore it open right there at the end of her driveway and read it:

TOXICOLOGY REPORT OF MARTHA ANDREWS

Her eyes ran over the two-page report.

And then she read it through again.

Martha had the constitution of an ox. When she had started complaining about stomach pains and cramps, they thought nothing of it. Then she lost her appetite. Martha was one of those women who could tuck away food like no one’s business, ate like a Marine. Martha got sicker. Nauseous all the time. Terrible headaches. The doctors were less than useless. Patti watched her slip away a little more each day.

A suspicion tiptoed into Patti’s thoughts, becoming increasingly intrusive. It started when she read through Martha’s papers, her sister had been re-visioning fairy tales in modern times, and the story she left unfinished was about a witch who was killing her neighbors with sweets and treats she brought by. It was not a big leap to cast Rhetta Brown as the witch. She had visited, all concerned, all neighborly, every couple of days at the back door. A glowing hatred took hold of Patti, illuminating everything: Rhetta cozying up to Martha once they discovered they were both writers, mystery writers, and how they got to sharing their scribblings with each other, how Martha encouraged her, told her about workshops and classes, but Patti knew full well that the pest next door’s work was pure tripe, and that Martha had a genuine gift, always had. It stood to reason that Rhetta nursed a resentment toward the better writer. Maybe it wasn’t much to be a motive for murder, but not completely out of the question, either. She knew writers to be a touchy bunch. That Brown character was unbalanced, anyone could see that.

As the weeks passed, Patti had been able to convince herself she was right, over and over she ruminated on it until it seemed clear as anything—Rheta Brown had killed Martha.

When the coroner had asked about an autopsy and a toxicology report, of course she said yes because from the very beginning she smelled something off. This would dispute any doubt. This would be incontrovertible fact. In the meantime, Patti would watch. And wait.

And now she held in her hands the coroner’s report. There was nothing. Nothing in Martha’s system. No poison.

Nothing.

The cause of death remained “Natural Causes.”

She was wrong.

Had been wrong. The whole time. She had leapt to conclusions, believed in a complete fabrication of her own mind. Patti felt all the air escape her lungs. A bell clanged in her head as the full reality of the truth rang through her. She had convicted Rhetta Brown of the crime in her heart and hated the woman with every cell of her body.

The two pages, the torn envelop, the store circular and the postcard, fell from her hands and fluttered down to the ground silently. She headed toward the stable, her old boots shuffled on the dusty driveway as she dragged shut the heavy doors behind her. Alone in the darkness, she went up to the wagon, touched it with the tips of her fingers lovingly, a caress that remembered long days on endless stretches of road, windows open, radio blaring. Happy times. Inside, she pulled the door, heard the solid thunk as it closed. She sat behind the wheel, turned the key in the ignition. With a satisfied sigh she leaned into the leather upholstery, the engine tuned over with a soft rumble and a roar. The chrome exhaust pipe rattled as smoke plumed out, thick smoke that hung like a haze in the air.

* * *

Caroline flew through the red light, cutting off two bicyclists and a kid on an electric scooter who told her to get bent. She told him to get bent right back. But it wasn’t fun and games; if she got stopped by the cops she’d be screwed. Three strikes, you’re done. So she gunned out of there. The Square was poorly designed to accommodate traffic now that they added the bike lane to the already narrow network of roads, but she was emboldened.

She had just made the turn into the residential neighborhood, gave a little outlaw whoop, when she heard sirens behind her.

Fuck.

She scrambled through the detritus around her for gum, a mint, something, willing herself to be sober enough to charm her way out of trouble and knowing it was probably a lost cause. Blue lights flashed in her rearview. The sirens got louder. She dutifully pulled over in the shade of an ancient tree, rolled down her window the rest of the way. She breathed into her hand to gauge just how bad her breath was. Fuck.

Caroline was not a praying woman, but in moments of dire consequences of her ill-fated choices, which were many, she did have a mantra which she repeated now, her eyes closed tight and her voice barely a whisper: Holy shit Please Please PLEASE holy shit holy shit I’m fucked please please I promise oh please

The speeding cruiser with its lights flashing passed her. And kept going. Then another whooshed by. When she opened her eyes, she saw an ambulance fast approaching, and further away, the shriek of a fire truck could be heard over the pounding of her heart in her chest.

For the second time in less than 24 hours, neighbors came to their doors and windows to watch something unfolding in their midst as the house at 217 was buzzing with activity. Caroline peered through the pollen coated windshield. A team of paramedics carried a stretcher. A body hastily covered in a white sheet. A man’s shoe, careworn and scuffed, poked out as the crew jostled into the back of the idling ambulance.

* * *

Jeffery Brown was dead.

iv

Who Killed Rhetta Brown?

The car hugs the curving road as it snakes its way down from the beach. A snow fell during the long night, but the morning is silent, everything blazes white and still. Even the gulls seem frozen in flight overhead. The road dips for a stretch, a thin ribbon to skate along under arching tree limbs heavy with snow.

“Be careful,” Martha says, laughing.

Martha. Has she been here this whole time?

“Of course,” her sister says, “Don’t ask silly questions. Just watch the road.”

Patti feels like she just woke up from a dream, or maybe this is the dream, but no. She feels the steering wheel, the cold seeping through her old gloves, she can feel the tires gripping for purchase on the slick downslope. Along the sides of the road, she can see clearly ice forming on the tips of beach grasses glistening with the brightness of tears.