A Valentine for the Widow of Rock and Roll

by Rene Diedrich

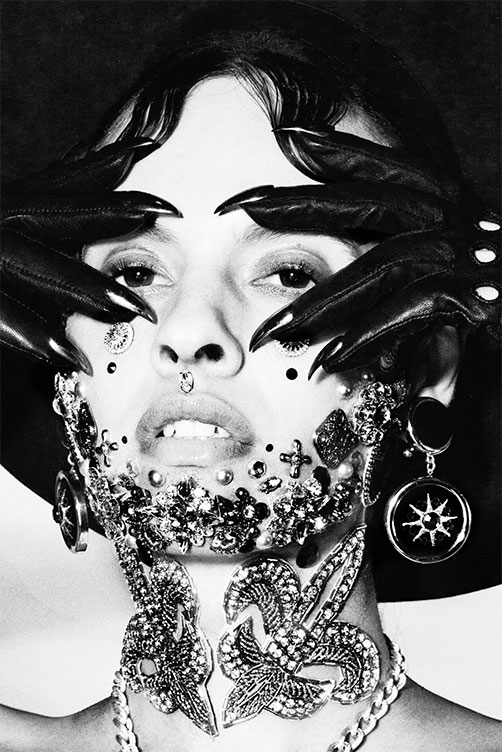

On the phone she sounded like she had a carton a day habit. “Old semen throat” is what my father used to call those bar bitches with that harsh bark for a voice he knew from the honky-tonks. An occupational hazard for bar maids, whores and other hard luck harpies who were well past the expiration date stamped on womankind. The voice did not belong to her photo, which was of a smiling blond woman, stunning and sophisticated, decidedly hip beneath a sweep of long bangs, black leather collar flipped up just so. Rock and roll’s widow called just as I was headed out of Long Beach to let me know she’d overslept. It was two, the time I told her I’d probably hit town. I am a punctual person because simply put, I hate to wait for others, and I see tardiness as a passive-aggressive slight when it is chronic, but have gotten slick enough to anticipate rather than react to people who are flakey. I adapt to accommodate myself and them, and the widow was relieved to hear I was just hitting the 405 when she was rolling out of bed. “We are a lot alike,” she noted, and I wondered how true that was as I drifted up the lull of the 101 on a Saturday afternoon. The lush green hills rolled beneath a rain scrubbed sky, so blue, so bright, it was blindingly beautiful behind my vintage tortoise shell shades, a thrift store score like my clunky red Mary Janes, which eased the gas pedal from an impulse to speed because everyone else was. Open highways are so tempting, but there was no hurry. The widow needed time to pull herself together and so did I.

I had all but unraveled by the time I hit the quaint coastal town she now lives in.

I called the number on my cell phone to ask how to get to the Vagabond where she said I should stay. The now softer voice on the other end babbled incoherently, offering too much information when all I needed was the name of a street. She was openly exasperated when I admitted I had no sense of direction and no idea what was east or west unless I could see the ocean or a freeway sign designating my destination.

“I don’t understand people who have no sense of direction!” she croaked over the crackling cell phone line. An unrepentant pot head, I knew some of my most basic motor skills were somewhat compromised by my wake and bake rituals, but all the landmarks and anecdotal digressions were confounding my quest, so I interjected something about needing no more than the street’s name.

To my horror, the widow began to spew a profane rant.

Suddenly, my serene demeanor shifted into an instinctive vigilance. Shit, what had I gotten myself into? A powerful craving for blackberry brandy seized my being, and I extracted myself from the conversation by assuring her I knew the way now.

And, as it turned out, I did find the place, which was nestled beside the sea and a freeway ramp along a quaint strip of little liquor stores, cafes, tidy motels and modest tract housing. I smoked a clove in the truck, shoving assorted shit into my big canvas Siddhartha bag and touching up my war paint in the rearview. Checking into a motel alone always makes me feel conspicuous, like some refugee on America’s Most Wanted or an AWOL housewife.

Of course motel clerks probably don’t think about the guests that go in and out of their daily grind the way I would.

It was, however, Valentine’s weekend, the plain Jane clerk explained when she quoted $110 for the evening and I gasped, head shaking as I made a grab for my card. I had the disposable cash to spare thanks to my tax refund, but it was an extravagance I could not indulge after my recent trip to the dispensary for compassionate care that came in pungent plastic containers labeled with names like Gorilla Kush and Twisted Sister, a high end hybrid I had along for this ride. The girl behind the counter banged the keyboard and said, “Have the Deluxe suite for $80.”

I surrendered my card, thinking of the dark drive home after a long night with the widow of Rock and Roll, who alluded to her living conditions as a source of stress but offered few details in our e-mail exchanges. I had a pretty good idea what the trouble was,

“My boyfriend broke up with me today,” the Vagabond clerk confessed as she did the paperwork. Her demeanor was flat. I looked at her clean, lightly freckled face, which was full, wholesome like a girl carrying pails of milk across a field in an old painting I saw once.

An ex of mine had sent flowers that morning, a lovely collection of yellow, red and peach roses, and he knew better. He knew if he was going to send me a gift to ease his guilty conscious I preferred something more practical. All my exes send flowers before and after the do hard time as my boyfriend . They feel obligated, but it just hit me how much this holiday meant to most women.

This girl didn’t expect much. But she surely did not expect she’d be dumped. She didn’t seem high maintenance to me. She did not even give herself the luxury of emoting . I did so for her: “That insensitive bastard,” I blurted out before I could consider the rhetorical ramifications of cursing in the sanitized office of a seaside motel in front of this plump, pale picture of pastoral womanhood. She was about half my age, and I felt a deep pang of empathy because I knew of this ploy.

A guy breaks it off with a girl just before Valentine’s Day because he is desperate to avoid the inherent perils of how he handles the celebration, which women, of course, tend to read as a declaration of the depths of their romance. It betrays how easy it is to misunderstand sex and friendship especially in the context of a consumer driven culture.

The girl’s blue eyes were not yet clouded by the stormy and sorted side of the fairy tales she probably grew up on, but she was sure of it when she said, “I am through with him and and lov,” her chin defiantly gestured to a garland of gory pink and red hearts adorning the lobby windows.

“It is,” I assured her, “more trouble than it’s worth.”

This blue collar kid was grounded in an oddly astute yet elusive reality a woman like the widow could never quite comprehend.

She loved her rock god for several dizzy, debauchery driven and degrading decades before he died, leaving her little more than the dubious fame of being his girlfriend back in the day. He was an obscure footnote in the Rock and Roll hall of fame when she became his wife. Broke and broken, he beat he, she says, r when he drank, which was all the time, for much of the life they had as husband and wife. Now years after it ended with his death, she was blue because she didn’t get to say goodbye. Love plays dirty tricks on the dirty girl.

The Vagabond’s desk clerk gave me keys to a room next to the office, which may have been a random thing or policy for women checking in alone or the gods whispering what was best for me. Maybe she knew I wasn’t going to get any this weekend either, so it didn’t matter that so many people were passing through this intersection beside the stairs.

There was an ice maker and coke machine near the door, I noticed as I thanked her for the discount, knowing she’d fall again. We all do, even when we know better.

Part 2

The widow herself was flawless. Her face like a doll’s, her thick blonde main shining and thick as it fell perfectly along those tiny shoulders along her ample bosom. Silicon bulges and purple veins betrayed what most assumed. Sixty year old women do not defy gravity. Not with tits like this. Tiny women rarely come with tits like this, but I did not argue as she defended the D-cup marvels. Maybe she was the real deal. Who knew? Who cared?

Her little hut in the tweaker compound was a sad, windowless cave with cardboard boxes full of crap scattered and stacked in some surreal configuration only she could comprehend. It was far from the worst dump I’d been in. I’d grown up in much worse when I was fortunate enough to have shelter. Nevertheless, even in the Valentine’s day drizzle that wept when dusk began a slow descent, I could smell the stench of the large scroungy mutts lounging outside.

The timber wolf emerged from the dark cluttered bed room on long uncertain legs. It sniffed in my general direction and followed it’s snout. It collapsed at my feet like a rescued hostage. The widow began to cuss the poor beast out. It looked up with weary gold flickering in it’s eyes. It’s expression seemed more human than any I’d seen before. I’d spent a little over an hour with the widow. I had a fairly sound grasp of what the wolf suffered. I felt rather trapped myself as she made Kahlua and coffee in chipped mugs stained with fuchsia lipstick in the dark dirty kitchen. I wanted to go but forced myself to stay. And stay. I was not sure what for or why. I just needed to see what happened.

She was bitching about her living conditions. About her rock and roll crap shoot. A book her late mate penned except for a lucid forward she believed would be a nice final score, the millions she needed to get through the next decade or two looking like a wax figure of herself 30 years before. As usual He blew it. I had been hopeful about ghostwriting.

But this wench made Norma Desmond hack duty look like a cakewalk. I couldn’t imagine being married to her, but Killer managed to survive a long time in her clutches. . The big hapless oaf even had a few final joyous moments because he just wanted the band to play together again and they had. When they did it was big televised show, too.

After meeting the widow, I was certain ARTHUR aka Killer Kane was luckier than anyone knew. “Dumb fucker! Died broke. ” She spoke this monologue as if he were listening. The wolf’s eyes bore into my soul. I think it was trying to tell me something. I spoke to it in whispers. These were secret subtle gestures I recalled from girlhood when I ran through the trailer parks barefoot, every mutt in the hood happily trailing after me. In college I had a hybrid. A shy lone wolf I called Los, who had a weakness for Nick Cave songs. Dogs can be pounced, bounced and trounced. Wolves need to be wooed.

While I prefer cats, who are drawn to me but not necessarily under my influence, I have had an odd intuitive rapport with most dogs for as long as I can recall. A police dog bit me when I was very small. One of my first memories It was tied up in the sun and mad, barking and barking. After the ER, I slipped out again, bandaged up, and fearlessly approached the dog again, only more slowly until it finally sunk gratefully into my lap as I stroked it and softly sang Nancy Sinatra songs with my own lyrics. “You keep trying to bite off my fingers, but confess . .”

Once a St. Bernard caught a whiff of strange mutt on me in someone’s back yard. It was a child’s party, and sweltering hot when it lurched for my small form suddenly. I recall the eyes. Red with rage as it opened it’s great mouth to devour me. I found myself at the top of a tree in the next second. Bleeding a little where it’s ghastly fangs caught my slim brown arm, I felt happy I wasn’t mauled until everyone below began to freak out. There were angry voices, arguments. Finally there was common sense. Someone said the dog should be put down since it was 100 degrees and the poor old creature was wearing three mink coats and delirious enough to go after a little girl less than half it’s size.

“This is the right thing.” The wise old granny declared.

But I protested.

“Humane,” the granny explained. “Sometimes life just ain’t worth suffering.”

I would not protest now. I learned eventually what she meant but never grasped it more completely than I did knowing I could not deliver the mercy of death to the widow’s wolf. I peered into the feral face of this wild thing kept in crippling small spaces with a lunatic. I longed to take him to the beach. To let him run himself to death, but this would mean consoling the widow.

I arched my eyebrows as if the wolf actually understood my all but articulated thoughts.

This was asking a bit much. An image of the widow weeping into my shoulder sent a shudder through my spine. I am not up to an Exorcism right now I told myself then the wolf, who was getting pushy, I thought. The widow kept talking and I kept making affirmative noises so she thought I cared what she was saying.

I sunk out of my chair, laid my body lightly across the long scary skin, bones and fur. I listened to the steady strong beat of it’s feral heart. No, it was not going to happen anytime soon.it looked up at me in misery. I tried to figure out how to kill it and make a get-away.

I would text Gonzo Girl to call me so I could escape before the creature succumbed to sweet eternal slumber. He liked the sound of that. There seemed to be hope in its eyes as I desperately dug into my big purse in search of some kind of painless cure for life. Vicodin? Muscle relaxers? Midol? Chocolate? All of my mercy was back at the Vagabond. I felt sure the wolf was exasperated by me. It sighed and dropped it’s body to the floor. “Sorry,” I whispered, feeling guilty.

It got up, weaved in a few ritualistic circles and fell in front of the kitchen entry just as the widow was finally delivering our libations. Her tiny high heeled boots were surprisingly deft and she nimbly hopped over the length of the wolf which had to be at least five feet. She was unnerved by this. A fall could be catastrophe at her age and with so many accessories sewn in.

She said over and over she wasn’t crazy.

“The wolf is passive aggressive! ”She insisted.

I thought suicidal was more likely.

“Fuck you. Son of bitch! Did yah see that? This motherfucker is trying to kill me!”

I tried to defend the wolf lamely, but I was pretty sure he was trying to kill her or at least maim her and I didn’t blame him. Afraid she was going to beat the poor thing, I urged her to sit down, toasted to her literary success and begged her to tell me about ARTHUR

When I spoke the name, the wolf seemed to look up in response.

“He’s here,” she announced as she pulled a Kool from a case covered in pink rhinestones, struggled to get fire from a mutilated Bic. She would swear until I tossed her my lighter. Even I was relieved as she exhaled the calming breath of nicotine smoke.

The wolf and I cowered beneath the heavy clouds of it. It was toxic like the sound of her voice as she nagged him. “He’s here!”

“Who?” I asked just to be sure.

I looked toward the door, expecting one of the tweakers to appear. “Arthur !” she said, the fag dangling from her heavy gloss as she squinted and puffed. I took a pull from the cup. I was pretty sure Arthur was there and had been all along. He didn’t want to be. None of us did.

But we had no choice. “He is tied to me,” the widow answered my thoughts. “Mormons are like wolves. They mate for life.”

I grabbed the book ARTHUR penned before a brief but successful comeback that made his sudden death somehow less severe. Except for the widow.

She didn’t love him exactly, but he owed her. ARTHUR owed her and he knew it. It seemed that her late husband was much like the wolf. Transparent, teetering weakly between realms and bound to this ferocious blond creature. The wolf was far less forgiving than Arthur, who blamed himself for being such a boozer and for turning her out on the streets to bring in some money when the band broke up. He had called her a whore, but he admitted he made her into one.

She was busy texting someone as I read Arthur’s occasionally self indulgent memoir. He rarely alluded to his wife. He had great loathing and affection for his band though. His life revolved around the few frenzied years they came up to crash and burn like some apocalyptic comet.

None of them became musicians until it was all over, except ARTHUR , who was a naturally gifted if not ungainly bassist in drag. This was part of their genius, but Arthur didn’t have this sort of insight or a sense of humor. His friends forgave him for this, for his addictions and for being unbearable.

His wife was not so generous. Nor as forgivable. It seemed to me that as the wolf watched intently, Arthur read over my shoulder, the light and shadows dancing towards darkness across the filthy walls. I gulped my drink as I sat, finishing the slim paperback in 45 minutes or so.

I had questions for the widow but no buzz. I began another desperate quest through my bag. I was sure I had some bomb ass twisted sister squirrelled away for the interview. I could smell the sweet pungent stank.

Then I realized that was grass not grass. The wolf farted. I felt the wind rise up and travel across my cheeks. It was a dry dead stench. Nice. I was mad dogging a sick timber wolf and thinking: Hey man, I can’t just murder you. That bitch is crazy.

Dear God, I wanted to bellow, just let me throttle the misery from it’s wise old eyes. Let me liberate it with a pillow or a bullet at close range. I had never killed anything on purpose, and my accidental death toll was limited to road kill: Kamikaze pigeons, toad invasions I had to drive through. And to my everlasting shame, I killed a canary when I let it fraternize happily with wild lice ridden sparrows.

He was never that yellow and he never sang like that until he had his lowly companions outside the cage. I lingered on the last few pages long after the book lost my interest. I scribbled maniacally in a note book. How the fuck did I coax this crazy bitch out of this cave? Before I became totally delusional.

“I got a killer stash of Kush at the motel,” I mentioned. A few times. I did not want to be on this tweaker compound when night fell. I didn’t want to go all- tell-tale- heart on that timber wolf either.

“Were they making meth,” I asked the widow. Maybe the fumes. . . The widow said, “probably” and sprung from her chair. She spent the next half hour in scattered activity.

“You gonna wear that?” she eyed me with scorn. I wore a well cut pair of jeans, a turtleneck and my deep red Mary Janes with chunky heels. To appease her, I grabbed my makeup bag and began to paint more layers onto my face. All I had besides were a torn up tee shirt and some cut offs I was going to wear the next day.

“Christ ,” she said to Arthur who was trying to disappear beneath the lamp. “Remember, back in the day bitches when used to get all dolled up and so did their men?”

I was still a lump of adolescent tomboy when Arthur and his band made punk rock new in the 70s. The drummer did himself in with a hot shot of heroin. The singer, a leathery low life Mick Jagger wanna be became a novelty act with a stupid song and a few small embarrassing comic cameos in bad movies. I could barely stand the sight of him. The guitarist, who the widow clearly still carried a torch for, had enjoyed some success with his bands and the debauchery of the performances. I’d seen him perform at a little club in Long Beach many moons before. I remember being about 20 years old and feeling somehow offended by his orgiastic excess with some 14 year old groupie he paddled on stage. My date was in ecstasy until the heavily mascaraed punk nodded out and the little goth girl began to steal the show by turning his paddle on him. I did not mention this as I tried to push the widow to the door. It was almost dark. I felt desperate. Like the undead were soon going to rise to drink blood, crave brains and undermine Democracy. I kept bragging about the weed. It was that good. I knew my weed. But what I needed was a stiff belt of blackberry brandy. This I did mention at least once as I licked the rim of her cup after sucking up the toddy she barely bothered to taste. It only made my contact high more contentious.

“I need something to take the edge off,” I heard myself pleading.

The widow understood this if not me. “Just like Arthur,” she said as if she knew something I didn’t.

It did strike me as strange he also drank the thick sweet nectar as every pint I ever picked up in a liquor store was thick with dust and the clerk blinked at me, got Black Label and ultimately let me find the deep purple curves of my old friend Hiram Walker. The pints sat so long they were still marked under Ten bucks. Of course, discriminating wastes of skin prefer cheap elixirs that are strong, quick and deceptively easy to pull. And the widow would drive most people to strong drink. Or worse.

I finally had her out the door, where she kicked at the fat lazy hounds letting flies eat their ears. They scattered in different directions. The wolf watched with disinterest as we left. I wished it well. I wished it death. If I came back, I promised myself I’d have something to help it get free of its mortal coil. Arthur was no longer with us, I thought, closing the door. And the widow in her spooky way seemed to hear what I was thinking.

“Arthur,” the widow explained, “is a homebody.”

“Me too,” I told her and myself catching the evening chill. We passed several small stucco shacks like hers. It was rocky, uneven ground with weeds sprouting up and no light except for a glowering full moon behind some clouds. Her sharp little heels made walking an act of incredible balance. She was a true party girl. She trudged ahead, cussing and all but blind as I followed in my heavy heels, hair wild, and face unbearably ordinary because all I had was cheap drugstore cosmetics. The widow was old enough to be my mother, but I was dowdy, sexless. She actually mentioned a daughter she gave up when she was quite young. The woman was adamant she wanted nothing to do with the widow. My math skills were not much to brag about, but her only child was indeed around my age.

“How old are you?” the widow demanded as if she heard my thoughts again as they were weaving around in my head.

I told her my age.

“You seem younger.” she noted this, an apt enough observation, but it was not a compliment. I was a pudgy middle aged wreck beside her brassy beauty.

“My pretty face went to HELL,” I said suddenly as clairvoyant as she was.

“You know Iggy?” she was gushing. I didn’t know Iggy really. He had pushed me on stage and ordered roadies to put me on a huge speaker at a show once in the ’80s. I was being trampled when Iggy spotted me and sung down like Tarzan: “Keep her safe,” his big eyes ordered.

It wasn’t always so so heroic, but it was still cool another time at the Whiskey when he noted me alone among leaping gnomes at the stage, serene for a rare moment in life as the music throbbed through my body. He was so perplexed by how others kept a full foot away from me when he performed he thought about bashing me upside the head with a mic stand. He lifted it to threaten me. I smiled, sure he would miss if he was on one. I felt giddy because I seemed to spook him. I had little witchy tricks. It was peppermint oil. It kept me cool and seared the eyes of pale white punks. They wilted beside me.

I did meet him once. In the 90s I reviewed Little Caesar an album that was far better than much of what was on college playlists. Inside the notes, Iggy invited fans to drop him a note. I scribbled something stupid, crammed the note and the newspaper clipping in an envelope and could not believe he promptly responded, inviting me to interview him when he performed in Denver where I spent the grunge years. He had an entire section at the stage just for me, and grinded his crotch in my face through the first half of the show. The interview was sober and terse as his China girl kept close watch over us. Iggy was very sophisticated, polite and well spoken. He talked about being an anthropologist at some point, but my questions bored him. I am not so good at flirting, but I am not sure this was the problem. I started to tell the widow about Iggy and me when her curses flew.

A beer guy in a stained wife beater stood outside a crumbling garage. A hillbilly, I reasoned between his beard and the bare feet. As we got closer, I saw he was in need of a shower, his eyes wet and mad with amphetamine courage. He probably had a vat of felonies behind the ragged curtain that served as a door. I sniffed the sweet scent of rain. Her voice bounced off the night, full of foul fury. I felt myself flinch reflexively as the man smiled and spoke: ” You batshit crazy bitch, you won’t even let the dead rest!” The widow stomped past him, a verbal assault ringing through the quiet oceanside town.

“You gonna ride with her?” he was laughing as he saw my face fall. I had been so eager to leave I followed her without thinking. I rushed up to her banged up Mustang as she struggled to start it, catching a mouthful of pebbles and dust when she gunned it to life. It was a loud roar of sick pistons and screeching belts.

She looked at me and spat, “Get in.”

The hillbilly was shaking his head as he went back into the garage.

“Umm, where we going? My truck…”

She pushed the door open roughly and said the magic words: “Liquor Store.”

My ass was in the seat but the door swung out wide as she whipped the car in a circle that sent pebbles and dirt in all directions. She peeled out as I got my foot in, and the door slammed shut. I swallowed as she weaved at an ungodly speed through the alley behind the compound. She fiddled with the stereo and loud obnoxious hard rock Arthur would have loathed assaulted my being. She got lost a few times before we found the place a few blocks up the road. A homeless man greeted me as I rushed in to get the brandy, rolling papers and a huge bottle of water to fend off the hangover I saw in my not so distant future. The widow, added peanuts and a Pepsi to my order. I paid without complaint. Her friends from the Silicon Valley or wherever it was were waiting for us at the motel, she told me on the way back to the compound. There was a garage in front with a tidy cottage nestled behind it and a large white frame house in disrepair. Both looked vaguely respectable from the street and the huts were hidden deftly by walls and trees . No one was really out. I noted the same tweaker was in the same car fixing the same thing he was when I arrived a life time before. He was an Native American, serene despite his bloated pupils. He did not like the widow. But he was too kind to attack her in front of me if at all. When she asked him to look at my banged up pick up, he gave me a very fair quote for body work.

“It’s not a priority,” I kept telling her.

“She’s not about cosmetic,” the widow quipped.

This was true enough. The tweaker smiled at me and said the truck was a good one. Another man, small and whiskered had joined us as the florescent light from inside the shop flickered. ” Damn things get two maybe even three hundred thousand miles if you change the oil.”

I assured them I did this religiously every three months. And we talked about nothing while the widow texted with her tiny pink cell phone. The little guy looked over at her with disdain. He and the Native American were very cordial, careful to speak without cursing until I let loose with an life-giving “motherfucker.” They were impressed by the fact that I was a writer, though I tried to impress upon them with how obscure and freelance my efforts were.

“Naw, she showed us. You are a poet. And a college professor.”

“Sort of, ” I agreed.

ADJUNCT instructor turned urban high school teacher seemed rather mundane as the little man gushed about the book I was working on. I didn’t want to contradict the widow, but I didn’t want to pretend I was more than another knucklehead hoping to be more than nobody. My modesty made me more endearing, and a third man, wiry and compact came from the house behind the shop. This was the John who beat the widow. He was coiled up, dangerous, and owned the place. You could tell by the way the other two stood aside to let him take front and center. The widow watched as she punched her tiny keys— she was wary. He looked like any blue collar businessman. His eyes were bright, he was clean shaven, not quite handsome, at most a very fit fifty. He shook my hand, asked if the blue pick up belonged to me and made small talk until I began to fidget. I had to pee. I was not sure if DEA agents were lurking close by ready to raid this haven of tweakers and mangy old dogs. If Ashton Kutcher was punking me, it was going to be difficult to explain to the school board. I started to leave, irreverently asking the John to tell the widow to meet me at the Vagabond. Annoyance filled his small features. The Native American slid back to the deeper corners of the garage and the little fellow licked his lips. The owner joined the widow in the darkening shadows. She cowered a little, but their voices were too quiet to hear. She stumbled a little, offering to kiss his cheek. He recoiled and she waved, “I will meet you there.”

I jumped in the pick up, it started and I worked its wide unwieldy ass out of the spot and took off. The lights glimmering off the wet black asphalt were intoxicating. I wanted to keep driving up the 101 until I was too weary to go on. I wanted to sleep in some motel for days then drive back like I was another person. Instead I went the mile or so there was, eased the truck into a nice spot just outside my room and gathered my bags, my bottles, my wits and went inside the cool comforts of my seaside digs. I sat at the table, opened the bottle of brandy and took a sip. It was stiff and off or old batch. I took a longer pull then rolled a fat joint, enjoying the busy fingers that tugged at sticky green leaves as the buds grew fragrant. I stopped shaking as I fondled and tore. I smoked about half but felt little relief. I had done a line of speed that morning. It was not something I did often anymore. An acquaintance showed up as I was going and offered. It was a fine buzz while tempered by Kush and solitude. But much too intense for tweaker compounds, wolves, widows, and Arthur’s tortured ghost.

I sent Gonzo Girl another text: Dear God, this woman is mad. She lives with some John on a tweaker compound with a suicidal wolf and Arthur’s ghost. It is later in NYC and she was clubbing with friends when she gets the message. “OMG, she sent back.

She wanted all the details, but was distracted.

“So I am interviewing a 60 year old Domo who thinks shoving stilettos up an old pervs’s ass is therapeutic. Makes sense.”

GG gushed in drunken misspelled words, “I totally luv you!

I felt this way for her as well, but there was not enough Brandy to make me say it much less text it.

“Ditto.”I tapped out on my Blackberry. I took a second long pull and lit up the joint again. The herb was outstanding, but one stops getting stoned at some point. It is the taste, the smoke I loved . I was going to miss weed when I died. I was not sure the widow was coming. Part of me hoped she didn’t, most of me knew better. Her John may have decided to kick her ass or fuck her. He was calling the shots. But she would manipulate me into her melodrama if I didn’t watch out. Her John was half Arthur’s size, but it was obvious Arthur was harmless until his wife drove him to jump out windows or beat her off to keep from suffocating. Her story was never clear or consistent, but one caught on to who she and Arthur were quickly. She was probably the reason he soared as well as the reason he fell out with his band. I was scribbling barely legible thoughts into a notebook I would never look at again when she called to say she was on her way. It would take a half hour for her to get there I figured. I sighed as I did some last minute search on my laptop. Was Joey dead? I could not remember and I could not find much with google. I texted GG. She was appalled I did not know this vital fact before visiting the widow.

I felt otherwise, believing it best to be more than a groupie. Arthur fascinated me, but not as some Girly boy in a band that played shit one needed to hear live and at under 30 to fully appreciate. The loser who knew city bus lines, lived on a pauper’s income and makes no sense now that he’s humble and sober seems to be Autistic, perhaps confounded by Nerves that can’t quite serve his body. He is intelligent, articulate, deep and innocent. He is awkward and shy, unattractive. He takes himself too seriously. Yet there is a painful nobility in his naked interviews with some inspired fan, not even born yet when Arthur was storming NYC dives with his peculiar band. The fan films him for a documentary. He is the least flamboyant, he is not charismatic or photographic except in drag at angles his girlfriend, wife, ex and widow no doubt made him up for, found then posed just so. Ultimately she created killer Vain, who could perform in drag, all 7 feet of him poured into sequins, tights, torn lingerie and all that warpaint.

“The widow,” I texted GG, “is like Dr. Frankenstein. killer is her creature.”

“Yep,” she replied. “It took real talent to make Arthur into killer Kane.”

“True, that.” I answered.

Then picked up the lag: “She’s hitting on me. Trying to get me to rent a place up here. I wanted to live in Ventura but not with the widow in my house or hair.”

“She’s hot, right?” GG was especially charming when she was wasted.

Well, I have never met GG, but we have texted on assignment which we like lubricated with intimacy in these circumstances. She was my best friend.

“Are you out with Serenade?”asked, knowing GG had a hard on for her. I

I admired her candor, her sense of adventure.

“Yeah. We are dancing with Jimmies from New Jersey. Why?”

I pull one of her moves, which she assumes I don’t notice.

“The widow is hot like a porno star with a bit of class.” I explain. “She has none, though.”

“Would you do her?” GG pushes.

“If you mean kill her. Yes.”

It was as if I could hear GG erupt in girlish giggles as I did.

“Are you stoned? Are you drunk? So? Would ya do da widow?”

“I wouldn’t fuck that skank with your dick.” I chuckled again.

This really worked wonders on my edge. Apparently my texts were a big hit wherever Gonzo Girl was getting gonzo, but she and I agreed to part as her roll dogs pull her to another club and the widow begins to pound on my door a full ten minutes later than I predicted. My room reeks of dank excess, which the widow inhales like a true aficionado I feel a little softer towards her as she savors the roach beneath lush clouds. It is weird, she is like another person. Soft spoken, vaguely interested in what I am saying. She says she is educated, from a good family, and interested in psychology and the spirit. I attempt to take her lucid state wherever it leads. She occasionally rants when she talks about Joey Torrential.

“Is he dead?” I want to fucking know but dare not ask as neither answer bodes well. She is sure he would have made her a star. She never explains why he doesn’t. She slips into the present. Her predicament is pretty dire, I am liquored up enough to empathize with this. The guy is beating her down. She’s banged up beneath all the pancake. Such a tiny wisp of woman. It is hard to imagine her accepting such abuse. She is not used to it. She’s an abuser. But I saw her admiration for the John. I change the subject when she mentions me moving to Ventura and taking care of her. No stranger to such primitive ploys, she tells me she likes women. Is this what she thinks I am there for?

“Me too,” I concede, “but I don’t sleep with them.”

“You remind me of Arthur,” she says.

I am a little offended for some reason, but whatever it is she recognises in me reminds her of why she loved him at least for a little while.

“How do you pay for upkeep?” I ask referring to her weave, the airbrushed makeup, her Botox and so on.

“I have a lot of clients from the Internet. That’s why the asshole took away my netbook. But they still call me” her manicured fingers stroke the scuffed pink cell. She tells me how much she enjoys hurting these frail old men and assorted freaks. She is swooning in a skunk haze. Sixty and hot enough for men to pay her hundreds of dollars an hour to slap, poke, belittle, sodomise and humiliate them. There is a tap on my door.

“That’s Megan, ” squealed the widow, hopping up like some sorority sister jacked up on root beer floats at a slumber party. Megan is a tall, very thin blonde with eyes that float around in her head. She is my age, a spoiled suburban soccer mom and slurring her words. She keeps looking me over. Whatever kind of goggles she is wearing they have made my proletariat ass doable. The pair scoot off into the bathroom where soccer mom claims her undergarments are undone just as the widow mentions her latest black and blue souvenirs from Johnny Lovehate. Soccer Mom invites the widow to her split level in bum fuck domesticated. I am not sure where this or many places are. I have been there, but I can’t tell you much about them because they are gentrified, sterile and redundant. One is just like another.

I offer soccer mom the brandy before taking another desperate pull.

The widow intercepts the bottle before the long greedy fingers can grasp it.

“She doesn’t drink.”

I arched an eyebrow because clearly she did something. She was getting loopy and incoherent as it seemed to kick in.

“Hey,” I said,” I am not one to judge. I just want some.”

I was only half joking. But whatever soccer mom was imbibing I was not going to indulge with these two and soccer mom’s Ward Cleaver down the hall.

“You want some?” The soccer mom was suddenly belligerent.

On second thought. . .

Reluctantly I follow them back to soccer mom’s room. I understand why the widow suggests such a pricey motel. Dives up the street had to go for half what the Vagabond charged, if that. A bland, friendly fellow let’s us in, opens a beer for me and makes small talk while widow and soccer mom fall all over the bed, giggling. He ignores them and so do I as we pretend his job at the utility company is interesting. The only thing I remember is he was drug tested and going without weed to be sure since soccer mom lost her job at one of those firms behind the devastating unethical loans that left my hood in foreclosure. It startled me that he was so shameless about this, even annoyed because his wife is no longer bringing in her earnings at the expense of poor working slobs who could not afford the American Dream. I soon find myself following the giddy girls back to my room for more Kush. The widow is maternal and sisterly to soccer mom. When I ask soccer mom about homelenders.com, she waves off the insinuation that she is complicit in crimes. I am diplomatic. Not like me.

“Bullshit!” she shouts. “They know what they’re signing up for. Mofferpuckers begging me for ARM loans.”

Begging? Well, they may be,” I cannot believe I hear myself say, after bemoaning bank policy that only lends money to those who don’t really need it. “But you know it’s unethical to give it them.”

“Efffics?” soccer mom retorts trying to stay focused.

“Uh, yeah, you know,” I offer stupidly, “Doing the right thing? The greater good?”

“So what’s that got to do with business?”

“Clearly not much,” I snap, grateful I don’t have to defer to her because I wasn’t a trick. Or even some closet sex freak.

“Are you religious?” the widow asks as if guessing a riddle.

“God. No.” I reply.

Soccer mom climbs into the widow’s lap. She is tall, her legs are spindly, clinging to her like a spider money. I can see her spine beneath the Lycra top she wears. I decide soccer mom is more obnoxious than the widow. I am impressed by how patient and indulgent the widow is. And again, I think of the daughter she gave up. We say good night when soccer mom lasciviously gropes me or at me, unable to stand up. She can walk. Suddenly she begins to weep. Not for the first time in a very very long night. It comes out that she is swiping her daughter’s Oxycontin. The teenager from another union has cancer and it sounds bad, but not really. It’s awful, but I don’t care about some spoiled white brat in the burbs. I take great pains to look weary, sorry to see them go. We agree to meet for breakfast in the morning. There is a diner next to the motel. I am fond of diners, realizing I have had only meth, coffee, liquor, weed, cloves and weirdness all day long.I look at my Timex. It is not even midnight. I felt sure it was four AM when soccer mom’s unintelligible cheers bounced across the concrete. The freeway just behind the Vagabond boomeranged silence as I peered from behind the drapes. A mist was settling over Ventura with morning. The lights fizzled off at the diner. The ocean roared not too far off but, I wouldn’t make it there this time. No diner I decided, afraid I may run into Mr. Cleaver over his oatmeal while I nursed my bloody Mary and eggs.

I decided to take PCH back on Sunday morning, put on Velvet Underground, maybe some Lenny Cohen. I was half done with a half pint and stark raving sober. I really wanted to be on the road, to be home. But a headlight was out. I had been drinking. Indulging in psychoactive substances. I was night blind too. Fuck. I was telepathic with ancient timber wolves and seeing the ghost of a rock and roll savant. GG was probably still falling about on the electric streets of the Big Apple. I texted.

“Wait ’til I tell you about the soccer mom.”

“Oh you undercover Kerouac,” she seemed to coo in a misguided symbols.

“I am more disturbed,” I confess, “than anything.”

“Even Better.” Her phone dies.

Then mine does as if finalizing the end of another broadcasting day.

I crawl on the ugly bed spread, curl up and stare into the darkness until my mind finds peace.

Part 3

It seems like minutes later that I wake, amped-up like the speed has come back for an encore. I throw my shit together and dash out into a bright sparkling morning. By the time I hit a gas station it is almost 8 am. I send the widow an apologetic text. I have to get home . An emergency. My sitter, as it so happens calls no sooner than I hit send to ask that I come home soon as he does indeed have an appointment. I don’t ask. I assure him I will make it in time.

Heathcliff and Oliver have been up all night playing video games. My protege is burnt out as my son and I are catching our second wind. It dawns on me as I pull in that Heathcliff has evaded his girlfriend and Valentine’s day. I fixed him up with this great girl de Thalia Minerve Aster de Gallo. Everyone affectionately deferred to Gibby.

We bonded because I read her name the first day of class and blurted out, “OMG, you are named after a Butthole Surfer.”

“Is that like Bunnymen?” she grinned.

“Well, some would argue way cooler, but Echo and Gibby’s bands are like apples and oranges.”

“Cool.”

I was miffed by the time I parked the beast, a challenge on Sunday morning. I wanted to catch Heathcliff before he bailed. Thanks to the PS2 a ten year old boy with a gonzo mom and natural curiosity could be relatively safe on his own for half an hour. Of course the giddy freak that greeted me with maniacal laughter as I swung open the door to have a word with Heathcliff was another issue.

My look texted, “WTF?”

“Sorry,” he offered. “I was the flying sugarland express myself.” He look troubled. He had this brooding beauty that was complimented perversely by Gibby’s goofy charms She’d been good for him, but I was having concerns for her. Heathcliff was prone to dark deeds and secrets.

“Look,” I began as I caught a glimpse of the flowers my ex sent me (that baboon! I don’t want no stinking flowers; however, cash is useful).

“We both know this holiday is a sham and so does Gibby, but teenage girls are gloriously fickle beings.”

“I didn’t realize it was Valentine’s day until I was crashing last night after three Monster energy drinks, and I dunno. I dunno. But I gotta go find Gibbs and make it up to her.”

I dug into my Jean pocket pulled a dub out of the crumpled bills I had left.

“Take these,” I said shoving the money , bouquet and vase into his arms.

“For your mom,” I explained. I pulled a perfect purple daisy from the arrangement. I poked him with it, “for your girl.”

Always polite he pretended he was interested in where I was, what I was doing, “So, how was your thing?”

“Sixty year old Domo, incredible preservation, tweaker compound, sexually depraved soccer mom on Hillbilly Heroin, Timber Wolf and shy glam rocker ‘s ghost … Kind of dull in all honesty.”

Oliver has wild blue eyes and he cannot stop laughing.

“He is gonna crash hard.” Heathcliff notes, dashing off.

We all do.

BIO

Rene Diedrich lives in the lost coast with her teenage son Nick. She works as a poet, painter and writer.

Rene Diedrich lives in the lost coast with her teenage son Nick. She works as a poet, painter and writer.

Jesse Downing was the 2016 Moss Point High School valedictorian and is a current student at Millsaps College. His hobbies include writing, drawing, singing, and coding.

Jesse Downing was the 2016 Moss Point High School valedictorian and is a current student at Millsaps College. His hobbies include writing, drawing, singing, and coding.

Alexandra A. Reinecke is a writer and journalist who uses writing as a tool to encourage empathy and affect positive change.

Alexandra A. Reinecke is a writer and journalist who uses writing as a tool to encourage empathy and affect positive change.

Susan Kleinman’s short stories have appeared in The Baltimore Review, Inkwell, the William and Mary Review,

Susan Kleinman’s short stories have appeared in The Baltimore Review, Inkwell, the William and Mary Review,

Bruce McRae, a Canadian musician currently residing on Salt Spring Island BC, is a Pushcart nominee with over a thousand poems published internationally in magazines such as Poetry, Rattle and the North American Review. His books are ‘The So-Called Sonnets’ (Silenced Press), ‘An Unbecoming Fit Of Frenzy’ (Cawing Crow Press) and ‘Like As If” (Pskis Porch), all available via Amazon.

Bruce McRae, a Canadian musician currently residing on Salt Spring Island BC, is a Pushcart nominee with over a thousand poems published internationally in magazines such as Poetry, Rattle and the North American Review. His books are ‘The So-Called Sonnets’ (Silenced Press), ‘An Unbecoming Fit Of Frenzy’ (Cawing Crow Press) and ‘Like As If” (Pskis Porch), all available via Amazon.

Paul Garson lives and writes in Los Angeles, his articles regularly appearing in a variety of national and international periodicals. A graduate of the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars and USC Media Program, he has taught university composition and writing courses and served as staff Editor at several motorsport consumer magazines as well as penned two produced screenplays. Many of his features include his own photography, while his current book publications relate to his “photo-archeological” efforts relating to the history of WWII in Europe, through rare original photos collected from more than 20 countries. Links to the books can be found on Amazon.com. More info at

Paul Garson lives and writes in Los Angeles, his articles regularly appearing in a variety of national and international periodicals. A graduate of the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars and USC Media Program, he has taught university composition and writing courses and served as staff Editor at several motorsport consumer magazines as well as penned two produced screenplays. Many of his features include his own photography, while his current book publications relate to his “photo-archeological” efforts relating to the history of WWII in Europe, through rare original photos collected from more than 20 countries. Links to the books can be found on Amazon.com. More info at

Tara Isabel Zambrano moved from India to The United States two decades ago. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Healing Muse, Moon City Review, Bop Dead City, and others. She lives in Texas and is an Electrical Engineer by profession.

Tara Isabel Zambrano moved from India to The United States two decades ago. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Healing Muse, Moon City Review, Bop Dead City, and others. She lives in Texas and is an Electrical Engineer by profession.

Katie Strine tolerates life through literature with a side of bacon and dark beer. She lives in the east suburbs of Cleveland with her quirky family — husband, son and dog — who accompany her on oddball adventures. Stay in touch via LinkedIn for more.

Katie Strine tolerates life through literature with a side of bacon and dark beer. She lives in the east suburbs of Cleveland with her quirky family — husband, son and dog — who accompany her on oddball adventures. Stay in touch via LinkedIn for more.

Rene Diedrich lives in the lost coast with her teenage son Nick. She works as a poet, painter and writer.

Rene Diedrich lives in the lost coast with her teenage son Nick. She works as a poet, painter and writer.

Gayane M. Haroutyunyan is an Armenian-American poet living in Los Angeles. Her work appeared in Chaparral, Zetetic, and Apple Valley Review, among others. She holds an MFA in Poetry from Sarah Lawrence College. Her hobbies include daydreaming in public places, cooking, and traveling places with her heart.

Gayane M. Haroutyunyan is an Armenian-American poet living in Los Angeles. Her work appeared in Chaparral, Zetetic, and Apple Valley Review, among others. She holds an MFA in Poetry from Sarah Lawrence College. Her hobbies include daydreaming in public places, cooking, and traveling places with her heart.

Leah Holbrook Sackett is an adjunct lecturer in the English department at the University of Missouri – St. Louis. This is also where she earned her M.F.A. Additionally, she has published three short stories: A Point of Departure published with Connotation Press, Somebody Else in Kentucky published in Blacktop Passages, and The Birdcage Nests Within published with The Weekly Knob through Medium Daily Digest. Upcoming, her flash fiction entitled What the Looking Glass Reflects will be published in the spring 2017 issue of Zany Zygote Review.

Leah Holbrook Sackett is an adjunct lecturer in the English department at the University of Missouri – St. Louis. This is also where she earned her M.F.A. Additionally, she has published three short stories: A Point of Departure published with Connotation Press, Somebody Else in Kentucky published in Blacktop Passages, and The Birdcage Nests Within published with The Weekly Knob through Medium Daily Digest. Upcoming, her flash fiction entitled What the Looking Glass Reflects will be published in the spring 2017 issue of Zany Zygote Review.