The Art and Architecture of Writing

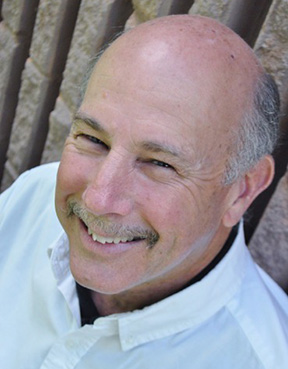

Alan Hess Interview

Alan Hess is a rare talent, he is both a writer and an architect. He has written several important books on architecture, including Googie: Fifties Coffee Shop Architecture, The Ranch House, The Architecture of John Lautner, Frank Lloyd Wright: Mid-Century Modern, and many others. Alan lives and breaths architecture and design. His mission, if you were to call it that, is to bring architecture—California architecture in particular—and all that it implies (education, preservation, appreciation), to the people. His work is both challenging and rewarding, which is to understand, educate and preserve the magnificent buildings that give life to our great cities, particularly here in Southern California—a place Alan calls home. Alan is a very busy man, always working on at least one major book or project. But he still made time for this interview, which we greatly appreciate.

Let’s talk about some of the projects you’re working on now.

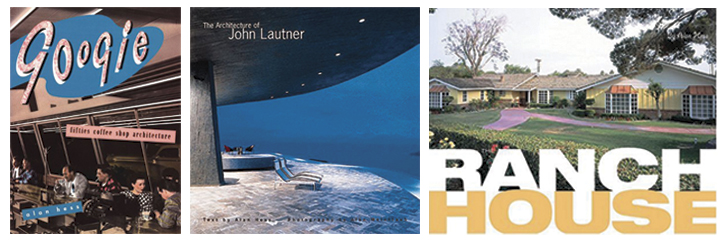

Right now I’m working on a book about California Modern Architecture, from 1900-1975. Most of the books I’ve worked on until now have been leading up to this idea. I’ve been writing now for thirty years. The first book was, Googie: Fifties Coffee Shop Architecture. I’ve mostly dealt with architectural issues in the west and the 20th century, suburbia and vernacular building types and their interaction with the high art architecture. And a lot needs to be said to pull together the entire story. I have a co-author, Pierluigi Serraino, so we’re working on it together.

What’s the status of the book now?

It will be published in spring 2017, so right now we’re trying to finalize the text. Hopefully in the next few months it will all come together. It’s a huge project, a little bit crazy.

It covers all of California?

Yes. It’s not an encyclopedia. It will give a framework for understanding the whole picture. It won’t include everybody and everything, but it will definitely bring in architects and types of building and trends that have not been given their due credit or attention. But it will include what is absolutely essential for understanding what California architecture in the 20th century was all about.

That sounds fantastic. I look forward to reading it. How do you go about constructing a book like this, with a subject so large.

We try to get away from a more traditional chronological architectural history, and away from the monograph of the individual architects, and show instead the inter-relationships between cultural trends, economic trends, demographic trends, as well as the inspirations and ideas of individual architects and their clients as well. The clients have a lot to do with architecture. Pierluigi and I are each writing half in individual chapters, based on what we’re interested in. So now we’re working on pulling it all together and making it cohesive. It’s still an unwieldy mass at this point. But it has a lot of interesting ideas and information.

When putting together a book of this size, how do you go about getting the images, permissions, and materials that go along with it?

That’s a very important part of this book. Pierluigi is an expert on architectural photo archives. Many of the sources have been unknown or have been neglected for decades. This book is not going to have the usual, expected photographs. It’s mostly going to be fresh, interesting images that have not been seen for decades—if at all. This will give everyone an idea of how wide-spread, and wide-ranging creative California architecture was in the 20th century. I’m very excited about these photographs. Frankly, though I’m a writer, I know most people buy my books for the photographs. So the publisher is helping to attain a lot of the rights. But we’re coming up with the images ourselves, from these new sources—which is one thing that will make this book exciting.

The Googie book has a lot of photographs you took yourself.

Yes, I consider myself an amateur photographer. I mostly take photographs to gather information. And some of the images turn out to be really interesting. I would like at some point to do a photography exhibit at a gallery with some of my older images. I started taking photographs in the 1970s when I was in architecture school. So a lot of the photos I took are of buildings that don’t exist anymore. So they have some value.

You studied architecture at UCLA. Where does the writing come from? How did you become a writer?

I’ve always been interested in writing, and I wrote for my high school and college newspapers. But I wasn’t all that good at it, and I didn’t really have something that interested me. But when I got into architecture school, I discovered after a while that I was really interested in writing about architecture, and the ideas of architecture. So I started to get the idea of writing seriously about the subject. There were a couple of books, this is in the late ‘70s, one by Steven Izenour, White Tower, and there was a book by Daniel Vieyra called Fill’er Up. These were small books, but on subjects that had never been written about before. White Tower is about the diner chain, and the other is about gas stations. That sort of vernacular architecture had never been given much serious attention at the time. But I was just fascinated by it. And the other book at the time was Learning from Las Vegas by Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour and Denise Scott Brown. But all of these books helped me understand Los Angeles, where I was living and studying architecture. So the architecture made sense suddenly. And that gave me the idea to use words and writing to analyze architecture, just as engineering equations and scale models are other ways. So writing was another way for me to understand architecture and what you’re designing. And I started looking around for an interesting subject that nobody else had written about.

Googie is a classic book for anyone who’s interested in unique and unusual Los Angeles architecture. Now that many of the buildings have been torn down, it’s also historically significant and important.

That’s the thing. It becomes a historical or archival document. Another purpose, as I moved along and became more interested in historical preservation, one of the purposes of my books was to help historic preservationists. So they could go before a city council or planning commission and say look, this must be important, there’s a book written about it. That actually impresses a lot of people. And that was another purpose in writing these books.

You also did a follow-up book on Googie.

Yes, the publisher came back to me almost twenty years later, and asked if I‘d like to do an updated version. It was a fantastic opportunity, because my first book wasn’t exactly my best. So it gave me a chance to improve my writing, but also there was so much more research and so much more I knew, I was able to extend the book. It’s at least twice as long as the original.

Growing up, did you do any writing? Were your parents writers? What kind of work did they do?

My mother was at home and raised us kids. And my father was an executive at Ford Motor Company. So I was around cars a lot, which I definitely had an interest in,

which also turn up in my books. We would get a new car every year. My brother and I would argue about what color and what kind, or if it had powers windows, which were really big at the time. We lived in California, but we also lived in Detroit for a period of time. We were right in the heart of car culture. My dad was transferred around to different places as I was growing up. So my personal experience of those places – San Francisco, Los Angeles, Detroit and Chicago – these major car culture cities in which I lived, definitely influenced my writing and understanding of these subjects. The cars I loved most were the 1956 Lincoln Continental, and the 1939 Continental. It was one of the most beautiful cars, and was designed by Edsel Ford, Henry Ford’s son. In the last several years, he has become a very important figure to me because he was at the heart of American industry and its economy, as well as American styling and industrial design and aesthetics, as the president of Ford Motor Company. As a sort of relief from working for his father—who was just awful to work for—Edsel would go over to the styling studio and work with the designers. And he actually designed some of the classic cars of the mid century – the Model A, the Lincoln Zephyr, which was one of the first streamlined automobiles, and the Continental. He died young, which is why he’s not as well known or appreciated.

So you started writing in high school?

Yes, but it wasn’t until I was in architecture school that I really had a subject that interested me seriously.

You’re quite unique in that you’re an architect and a writer – you’re sort of a hybrid – which is great. You’re someone who’s an authority on the subject they write about. What drew you to architecture, or made you want to become an architect? Was it a building or architect you admired?

I’ve always been interested in architecture, not originally as a profession, but as a personal interest of mine. My grandmother always admired Frank Lloyd Wright, and I saw a number of his buildings. I lived in Chicago in high school, and there are a number of his buildings there, as well as Louis Sullivan’s—which are just extraordinary.

And I went to a college that was designed by Bernard Maybeck, the great Bay Area California architect—which was great. There was a history professor there, Charles Hosmer, who was very well known in the preservation field. Everyone has a professor who really inspired them, and he inspired me. It wasn’t until I had to choose between going to law school and architecture school, that I really made the decision.

Frank Lloyd Wright was the first architect to inspire you.

Yes. He was a brilliant designer. Just to be inside one of his buildings or houses, we can understand how space and materials and ornament can be orchestrated to make life better. Extraordinary designs. He was a genius. Wright’s whole persona and his family motto was “Truth against the World,” the idea of the artist as the heroic individual, who mastered the problems of the world. And as a young, naïve, idealistic teenage boy, that appealed to me as well. But I got over that, thanks goodness. Frank Lloyd Wright inspired Ayn Rand’s book, The Fountainhead, which I read at the time. I got over that, too.

But it was an important moment for me at the time. I realized that I would never be Frank Lloyd Wright. But I realized that I could be myself. I could follow my own interests in architecture, and be able to contribute something of value. That kept me going. And when I began to write about architecture, I realized I was covering subjects that no one else was writing about. I saw the value in them and was able to express the importance of a diner or a motel or a car dealership. These were structures that almost nobody else had an interest in as far as architecture, but I did.

You’ve also written several books on Frank Lloyd Wright.

I saw some photographs by Alan Weintraub. He had a real interest and talent in photographing organic architecture, like Wright’s and John Lautner’s, as well as many others. Organic architecture is very difficult to capture in photography because it’s not designed from one point perspective, it’s something else. So Alan and I got together and started thinking about books we could do together. Later he got a contract to photograph all of Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings. So that’s where the series of books on Frank Lloyd Wright developed. I came up with a theme for each of the books. One is on his houses, one is on the Prairie School years, the mid century modern houses, the public buildings, etc.

For me it was exciting to come up with something fresh and interesting to say about those structures, and the ideas they had. I enjoyed writing them.

Name some writers who influenced your work.

Writers who are also architects or designers, like Esther McCoy, definitely a great writer; David Gebhard, a great historian and author; J.B. Jackson, cultural geographer; and John Beach—not as well known, but a friend of all of those people and a teacher at UCLA School of Architecture where I went. These are all authors who have some background in design, and are able to understand architecture and explain it in a way that art historians writing about architecture missed. They capture something about architecture.

As far as fiction writers, Jorge Amado. I spent time in Brazil, and his fiction about life there really captured the spirit, culture and people of Brazil. I also enjoy reading the fiction and non-fiction of Tom Wolfe.

When you start working on a new book, how do you begin – where do you start?

I’ve usually been thinking about it for a while, and I’ll start with some ideas and thoughts in my head. And then I’ll begin to pull together all the ideas I have. I’ll go and visit the buildings or places and see what strikes me. I’ll start talking to experts in the field, or the architects themselves, and in many cases I’ve been able to talk to the original architects. And that can be really fascinating. So it’s just a matter of finding an interesting subject, with something of value there, and trying to make it interesting. For me, writing is a process of discovery. I do not know what I’m going to write when I start. I sort of think as I write and figure out the direction of the project. That’s the fun of it—what makes it interesting. I just dive into the subject anywhere I can, and slowly the whole picture begins to reveal itself. I figure out what are the major points, the major landmarks, etc.

For my first book, I was interested in Googie architecture, but I didn’t know it was Googie architecture, until I started writing and learning more about the subject. I had seen these diners and restaurants before but had never really connected them. I started doing some research on the Bob’s Big Boy on Riverside in Toluca Lake. I called up Bob’s headquarters in Glendale and asked if they knew who the architect of the building was. They said it was Armét and Davis. So I called up Eldon Davis —their firm was on Wilshire Blvd. — and asked if they designed the Bob’s Big Boy in Toluca Lake. He said no, and I thought that was the end of it. But then he said, but we did design Ship’s La Cienega and Norm’s and Pann’s, and he began to give this list of all the coffee shops they designed. And I suddenly realized I had stumbled upon one of the most important designers in the field. It was at that point during the research that it all came together and I realized there was a subject worth writing about. That’s really great when that happens.

How did Googie get published? Did you approach a publisher, or did someone approach you?

I did write up a proposal. Barbara Goldstein was the editor of Arts and Architecture at the time, and I told her about my project. So she asked me to write an article about Googie architecture, so that was published. And since I had a published article that gave me a little credibility. So I sent the article along with my proposal to at least a dozen publishers, who had published books on similar types of architecture. I got two responses as I remember, Chronicle Books was one of them. And there was an editor, Bill LeBlond, who saw something in it, so that’s how I got my first contract.

When you’re putting a book together, you obviously work at a computer.

My first couple of books I typed. I sat on the floor and edited the pages by cutting them with scissors and taping them together. And then my mother, God bless her, typed it up clean, and I then re-edited it with scissors and tape, and she retyped it. So I went through several drafts that way. That was like in 1984. I think in 1986 or 1987 I got my first computer, which simplified the process by a lot.

I work on a Mac now. I have an iMac, but I really do most of my writing on an iPad. So basically I can go anywhere and write. I used an app called Pages.

I’m going to name a few important architects, mostly known for their work in California, and maybe you can say a few words about each one, what they did, etc.

Let’s start with John Lautner, who you also wrote a book about.

John Lautner was one of the greatest architects of the twentieth century. He worked with Frank Lloyd Wright, of course, but what I admired about him, and he told me this, was while he was a student and apprentice with Frank Lloyd Wright, he didn’t design that much. He said he was just absorbing and watching. It was only after he left Wright, and moved to Los Angeles and opened his own office, that he then began to really develop his own crucial way of designing. So many people who worked with Wright were so overwhelmed by the brilliance of Wright, that they pretty much just copied Frank Lloyd Wright. But that wasn’t good enough for Lautner. He had to digest it and make those ideas his own, and carried them on further than Wright. That’s one of the things that makes him so, so important. Taking some of those seminal ideas of Wright’s, bringing them to Los Angeles and applying them not only to houses, but also buildings of everyday life, like the original Googie’s coffee shop, and other drive-ins he did, and car dealerships. He saw virtually any kind of architecture as a legitimate architectural challenge to him, and to re-think everything from the fundamentals. I did an articles about him Fine Homebuilding magazine. And there was one house, I think the Mauer house in Los Angeles. And I asked him, where do you start on a design like that? And he said, “The hell if I know. I sweat a lot.” So the idea that someone who was as creative as Lautner, sweated over where to start on a new design, just impressed me to no end. So he took every project seriously in that way to dig down to find something original about it and to translate it into a design.

Richard Neutra.

Another great Los Angeles architect. I think he is misunderstood. He is usually praised and famous for being an Austrian, and for designing International Style buildings here in Los Angeles. And that’s partly true. But I think what is important about Neutra is not what he learned from studying architecture in Vienna before World War I, but how he responded to the environment of Los Angeles after he arrived here. He was fascinated by our construction methods, our indoor-outdoor lifestyle, our vernacular architecture of drive-ins, billboards and gas stations, and the influence of the car on architecture. He was a good enough architect to be influenced by all the new things going on around him here.

A. Quincy Jones.

Another fascinating architect, because of his variety. It was a perfect time in Los Angles, when the city was booming and there were all these different types of buildings. He worked on schools, housing, offices, car dealerships restaurants, you name it. And he was able to design a lot of different things, but in a very individual way. He was in many way Mr. Establishment, dean of the school of architecture at USC, and he had a lot of influence on many other architects – very well respected. Lautner was more a maverick, more on the edge, often misunderstood and criticized for his designs because they were so unusual. And Quincy jones was in the center of the profession. He and Lautner were friends, they appreciated each other’s work. And I think Lautner influenced Quincy Jones early in his career – in some of the early Quincy Jones houses in particular, there’s some very strong Lautnerian ideas about them.

Rudolph Schindler.

Schindler is one of my favorite architects. He was a lot like Lautner, but he started twenty or thirty years earlier. So he had a very different sort of career. He was known as a gregarious and fun loving individual, and that comes across in the buildings he designed—very creative.The first time I saw his own house on Kings Road on an architecture tour, and his wife, Pauline Schindler, was still living there, and I met her. I saw the house before it was restored. It’s concrete slab walls tilted up. Some of the interior walls were painted, pink as I recall. And it wasn’t that strongly constructed, so it had been altered over the years. But nonetheless, even through that, I could see that it was sort of the beginning of California Architecture, indoor/outdoor life, the way the outdoors carries into the interior space itself. Just brilliant on Schindler’s part, to be able to put together something like that. And like Neutra, Schindler was trained in Austria before WWI. But he allowed himself to really engage with Los Angeles—and the culture, and the materials, once he got here. I wrote an essay for the L.A. Review of Books, and the title was Schindler Goes Hollywood. And the idea was that Schindler and the other very good architects of California, didn’t just come here and start to do what they had been doing elsewhere. They interacted, and understood, and lived the culture that was here, and that changed their architecture. And schindler is probably one of the very best examples.

Gregory Ain.

Ain is another very good California architect. He worked with both Schindler and Neutra. He was a real socialist. A lot of architects that studied with him told me that he really believed, that the purpose of architecture was to improve the life of the average person. And so he tried in a couple of places to do some cooperative socialist housing. He never quite succeeded at it but the designs themselves are very, very nice.

Joseph Eichler.

Eichler was not an architect, he was a builder. He hired architects like Quincy Jones, Anshen & Allen, Claude Oakland and others to do his architecture, so he chose the very best. This is not to discredit Eichler, but he was often times credited with bringing modern design to mass produced housing—tract housing. There were a number of other really good architects and builders who were interested in modern mass produced architecture, like William Krisel and Dan Palmer– they were also doing modern tracts, and in some ways even more dramatically modern. There were quite a number of examples of modern architecture available for the average person in tract housing.

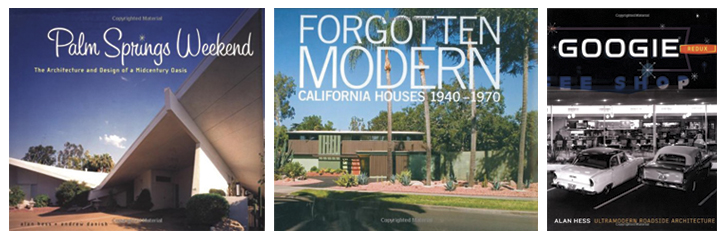

Palmer and Krisel.

In some ways their work was sort of my discovery during a book I wrote with Andrew Danish, Palm Springs Weekend, on midcentury architecture design. I never heard of Palmer and Krisel until I did the research for that book. They did a number of tract homes in Palm Springs. And fortunately, Bill Krisel is still around, so I was able to get to know him and interview him and see his archives first hand. And learn what it was like. He knew everybody and he did really interesting work himself. Their work deserves a lot more credit because they really did modern architecture. They were really devoted to bringing good modern design to the average person. And that was supposed to be one of the fundamental ideas of modernism, at the very beginning, from the Bauhaus, they were trying to make it for the average person. And Palmer and Krisel were one of the few architecture firms to achieve that. Gregory Ain was a great architect but he was never really able to build on a mass basis, and have that sort of impact. So I admire that, it cements their place in modern architecture in California. They were partners from the 1950s to the early 1960s, then they split and went their separate ways. I was able to interview Dan Palmer as well for a book I did on ranch houses before he passed away. There is a new book coming out in February 2016 about Krisel’s work in Palm Springs, in which I wrote one chapter.

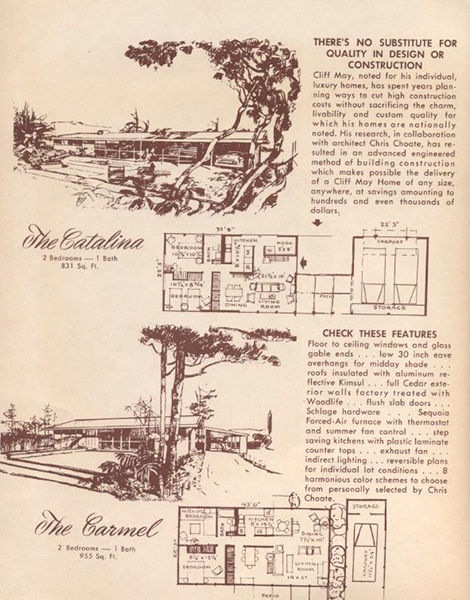

House designed by William Krisel

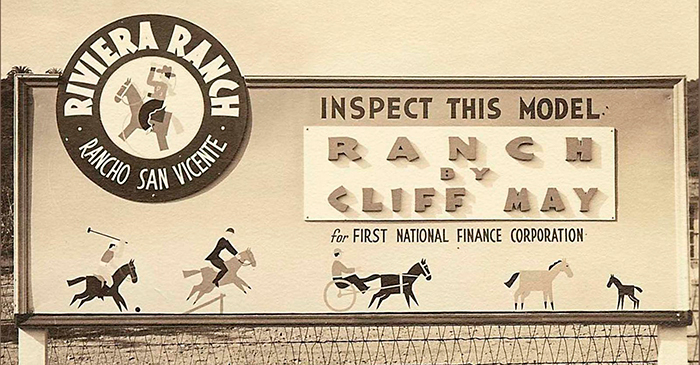

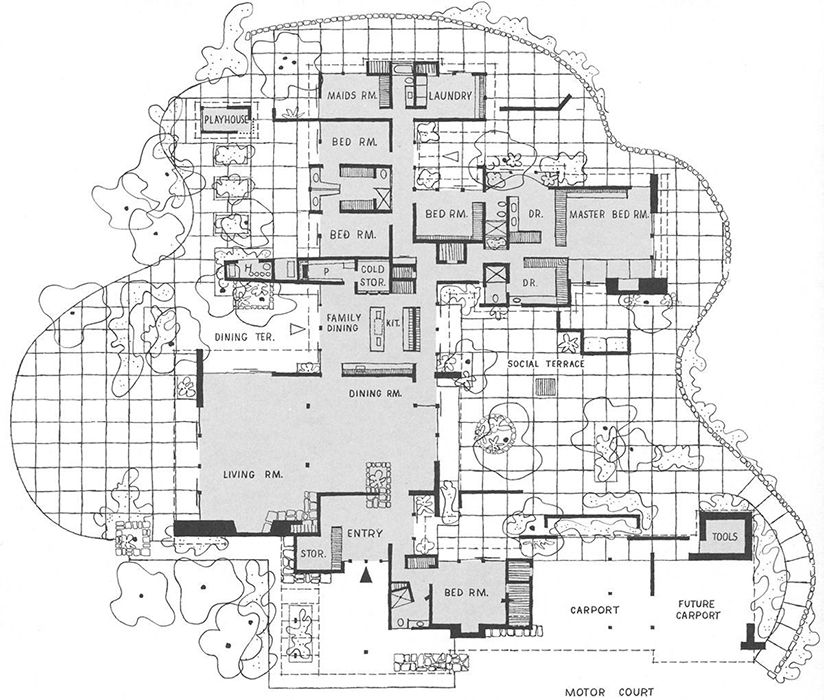

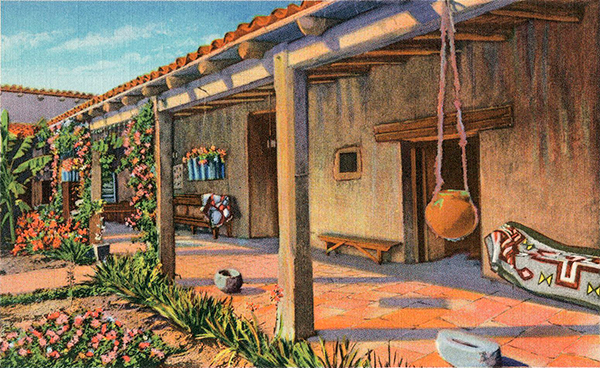

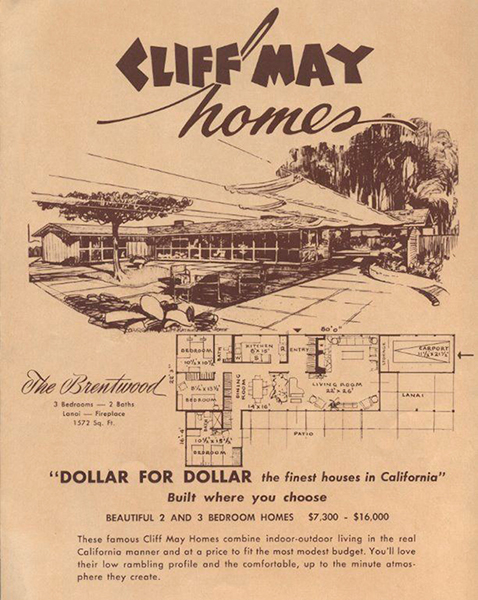

Cliff May.

Cliff May was a designer, a building designer. He had more impact on architects than most architects knew. And the reason why is fascinating. He did carpentry, he built furniture, he was a musician with a band, and he had an entertainer’s promotional attitude about his work. He understood people. And he was one of the people who understood the power of the image of the ranch house— the California ranch house. They were the adobe haciendas of the nineteenth century, and these wood shacks out in the country. And he realized there was an inherent glamor and certainly an architectural character to them—living indoors and outdoors and simplicity. And he was able to capture that in his custom designed, and mass-produced homes as well.

Edward Fickett.

Edward Fickett, is another name that had been long lost in terms of the general public. Certainly other architects knew him. And I was able to write about him in my book about the ranch house, so he could begin to be appreciated for what he really accomplished.

And in fact I grew up in one of his houses in Pasadena, a ranch house tract home. My parent’s bought the house in Hastings Ranch, brand new. And years and years later I had learned that He had designed Hastings Ranch. It’s more of a traditional ranch house, not modern, but nonetheless. He’s definitely one of the major architects of Southern California. His was known for his tract housing, which was quite extensive, and for many other types of buildings. That was one of the reasons I got into writing about architecture in the first place, was to let people know about these neglected talents. They need to be a part of our understanding of Los Angeles.

We need really good books written about these architects, like Edward Fickett and Gregory Ain. In recent years there has been a few good books written about Cliff May. There are a number of architects who deserve really good books. And I try to encourage other people to write them.

William Pereira.

I live in Irvine, which is a master planned community designed by William Pereira fifty years ago. It opened in 1965. Pereira was one of the major corporate offices in Los Angeles. He was usually critically neglected and dismissed, and initially, I didn’t think much of his work, until I started to do some research on him. And I began to realize that my entire concept of him was wrong. As I began to look into his buildings when I moved to Irvine, it really spurred more of my interest in his work. He is one of the major Southern California architects who shaped the region. He designed several key buildings that defined the way people lived, worked and played. He designed CBS Television City, a television studio at a time when television was brand new. So he designed this facility that is still in use today, with all the changes in the media. He also designed Marineland, a new type of playground out by the ocean for the citizens of Southern California, this urban metropolis, a place to take the kids, and learn. He designed LAX as well (along with Welton Becket and Paul Williams), he designed this jet port, before the jet airplane was even in use. And then he planned Irvine and the new university there. Suburbia was growing, but it was being criticized. Tract housing was often a hodge-podge, very randomly planned, and not coordinated. And Pereira, as a planner, said we can do better than this. It was sort of miraculous that the new city project of Irvine and UC Irvine came together. It’s a really interesting story. He took the ideas of suburbia and organized its elements in a way that made sense. There was a diversity of housing types. You were part of nature when you lived here with generous greenbelts. You had schools, libraries, shopping, swimming pools — everything you need in life, and you could walk to these places, so you didn’t have to be dependent on the car. This was the early 1960s when he designed all this. It was just extraordinary. In his career he really conceived and developed many of the ideas that made up Southern California. And he did it with style. Another building he designed was LACMA, which is the cultural capitol of Southern California, at a time when Los Angeles was the most modern city in the world. And there’s talk now that they want to tear this down, this cultural icon.

Paul Williams.

The socio and cultural history that his career represents is fascinating. An African American in Hollywood, and what he had to go through to become one of the most successful architects in California, throughout the mid century. It’s a great story, and he was a really good architect. He’s often called the architect to the stars. He built a lot of really big and beautiful, mostly traditionally styled homes. But he did a lot more than that. He did office buildings, he did housing tracts, he also did housing tracts for the African American community, here in Los Angeles, and in Las Vegas. After he stopped doing traditional styles, he adopted modernism, and modern methods, and was just as masterful. He is equally important as a role model and an architect. His influence on other architects is really important. There are a lot of people who got into the business because of Paul Williams.

Let’s talk about how you work. How much time do you spend writing each day? How much time do you spend on the internet, doing research? What is a regular work-day like for you?

Well, I spend too much time on the internet. I don’t know if email is really a blessing or not. But I usually start by checking my emails in the morning. I check Facebook. There’s a lot of good information on FB if you look in the right places. There are a lot of good sources for books and information going on now, also historical subjects. I do my creative writing in the afternoon, which includes writing and editing on various projects.

What do you know about William Mellenthin?

Not a whole lot, that he was a builder, very successful, building the traditional ranch style homes. When searching for specific information like this, a lot of it can be found on SurveyLA.

But we continually lose archives and historic information on figure like Mellenthin. Many important architects and builders could be lost to history. Like Wayne McAllister, one of my favorite architects. He designed the Bob’s Big Boy in Toluca Lake, and the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas. But all of his drive-in restaurants, which were built in the 1930s, which were everywhere, are all gone. There isn’t one remaining. So the information and the buildings are so fragile.

Out of curiosity, who designed the Casa de Cadillac car dealership in Sherman Oaks?

Casa de Cadillac was designed by Phillip Conklin with Randall Duell in 1949, it was a collaboration. It was originally called Don Lee Cadillac.

What kind of advice do you have for writers today? How to get their work out there and be published.

It’s a lot different from when I first started. Publishing on the internet serves the purpose of getting the information out there the way books once did. I would encourage people to write about architecture. There’s so much we don’t know, and much that we need to document. I was really pleased to learn that some people who’ve written books, were inspired by my work. There’s a book coming out next year on Trousdale Estates that Steven Price is writing. That’s a great subject and deserves to have a book about it, but I just don’t have time to write everything. But thank goodness someone else is doing it. And other people are doing books on Paul Laszlo and Tommy Tomson, for example, fascinating little-known architects. There are plenty of other subjects that people could be writing about, to document—getting it down—for the rest of us to understand.

I didn’t intend to be a writer. I was interested in architecture. And that’s why I write. I don’t write to be a writer, but to further the cause of good design.

What other projects/books would you like to work on?

I have a long list of projects I’d like to do. A couple of really interesting architects. The most intriguing subject that I would like to write about is the 1970s and ‘80s of California architecture, that hasn’t really been covered. It was touched upon in the Getty show, Pacific Standard Time, which was a few years ago now. The people are still around and the story has not really been told. And trying to figure out what actually happened in that period, and do it objectively, is a really interesting challenge. Some of these people are around and are telling their own histories, but not necessarily the entire story. So I would love to cover the entire story in context.

Alan recommends these essential books on Los Angeles architecture:

• Five California Architects, by Esther McCoy

• Exterior Decoration, by John Chase

• Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies by Reyner Banham

• Los Angeles: The City Observed by Charles Moore, Peter Becker, Regula Campbell

• Holy Land, by D. J. Waldie

• Google: Ultramodern Roadside Architecture, by Alan Hess

For more information about Alan Hess.