L.D. Zane

Kintsugi

by L.D. Zane

“You really shouldn’t go back into the house.” Dori, always the reassuring voice of reason, was concerned.

“And why not? I still have some things in the house which are mine, and I have the right to collect them.”

“This isn’t about rights. It’s about being smart and not giving them ammunition to use against you. And because your attorney advised against it. With you no longer on the deed, he said they could consider it trespassing. Knowing your brother, he’s just crazy enough to press charges.” There was no anger in her voice. It was more like trepidation, bordering on fear.

“He only advised against it. He didn’t say I shouldn’t or couldn’t do it.”

“It’s the same thing and you know it.”

“Maybe so, but how will they know when they’re in Florida?”

“There’s no maybe about it. Besides, I wouldn’t put it past him to have the neighbors watch the house and report to him. You know, Ian, you’re sounding like a child throwing a tantrum. I don’t know why you hired and paid for an attorney if you’re not going to follow his advice.”

I was one of a triad of owners of the house in which I grew up—the other two being my older brother and his mother. Even though she is our biological mother, I long ago stopped referring to her as my mother. I just refer to her by her name—Gertrude. My brother doesn’t feel the same way.

She caused the divide when I was born, about three years after my father returned from the battlefields of Europe. Gertrude had raised my brother, Henry, alone for the better part of two years—a year while my father was still in Europe, and another while he was recovering at an Army hospital in Kentucky from a third wound he suffered—this one at the German border, while serving with Patton’s Third Army. She insisted that since she bore the burden of raising Henry for the first two years of his life, and my father really had no bond with my brother after his return, that I would be his responsibility. “This one is yours,” Gertrude said to my father, matter-of-factly. Like two once-friends kids returning baseball cards.

I’ve never been sure why she felt that way. It didn’t seem natural. None of my friends’ parents ever did that—at least as far as I knew. Maybe she was just tired, didn’t really want me, or was angry at my father for leaving her, regardless of the circumstances. Nonetheless, it was a responsibility my father gladly and wholeheartedly accepted. I was his son, and my brother was hers. There was never any sense of kinship between me and my brother and his mother. It was like two separate and distinct families living in the same house.

My father would take me everywhere. He would only take Henry if he asked to come along, which wasn’t often, or when we went somewhere as a family—like on vacation, or to an Army reunion, or to visit my father’s family in Chicago.

When my father drove a delivery truck for a restaurant food service company, he would take me to make a weekend emergency delivery. The truck had a manual transmission with a huge shift lever on the floor, and he would let me shift it into gear. At eight years of age, that lever seemed as big as me. He would say, “Ready…go!” and I would push or pull the lever to the proper gear as he depressed the clutch. I had to use both hands and all of my strength. Even if I would grind the gear into place, he would always tell me I did a great job, and tousle my tangled crop of red hair.

He, too, had red, wavy hair—like many of his siblings and family members—and a fair complexion which accented his blue eyes. At six-two, and now in his early thirties with the same physique as when he left the Army, he was a strikingly handsome man with movie star looks, who always drew the gaze of ladies—even if he was with my mother, or they with another man—and even from a few envious men.

The man had a quiet intellect. With only a high school education, he could still finish The New York Times Sunday crossword puzzle in about an hour without the aid of a dictionary or thesaurus. Although he was a congenial guy who could make you his friend in an instant with his easy smile and soft-spoken manner, my father was a man of few words and fewer nuances who always kept his own counsel. When he spoke, there was no ambiguity. You listened.

One event still stands out. He took me by train to Philadelphia at a time when there was still passenger train service from our small town. He didn’t ask my brother to come along. Other than my trips to Chicago—which were cloistered visits to see my uncles, aunts and cousins—it was my first trip to a big city with my father as a personal guide. He stopped a policeman to ask directions to a museum. The officer had a blasé demeanor and didn’t look approachable—until my father addressed him. Each instantly recognized the other was in the war and began to chat.

“Ninety-Fifth Infantry Division. The Iron Men of Metz. Patton’s Third,” my father proudly stated.

“The Big Red One,” the officer responded with equal pride standing almost at attention.

“We fought and slept in the same mud and dirt,” my father said somberly.

“You bet we did, and we lived to tell about it. What can I do for you, soldier?”

“My son and I need directions. Can you help?”

The officer listened, then took out his note pad and wrote down the directions to the museum, and even suggested a few other sites of interest. My father introduced me to the officer, who shook my hand. After a few more minutes talking, they shook hands and slapped each other’s shoulders as they said good-bye, as if they were long-time friends. I suppose in a way, they were. I swear if the officer would have been allowed to do so, he would have used his police car as a taxi for us! My father was that good, but it wasn’t a front. He was genuine; the real deal. The best natural salesperson I have ever met.

My fondest memories, however, were of when I helped my father cook. He didn’t get the opportunity all that often with his work schedule, but how he enjoyed it when he did. The TV shows of the day portrayed a mother who stayed at home and prepared meals, and a family who sat for dinner in the dining room at a set time every day. This most definitely was not our home.

Gertrude owned a woman’s dress shop, and my father—before he finally landed a job with the post office and had a predictable schedule—rarely sat for meals with the rest of his family. He usually ate alone late at night, most times after his family was already in bed which, in retrospect, still saddens me. Perhaps that’s why I still would rather not eat than eat alone. But when he was able to do so, mostly on the weekends, he did the cooking. My brother and I were thankful, as Gertrude really had no desire, nor talent, for cooking. To this day, I do not eat at any place that advertises meals: Like Mother used to make.

One of my father’s favorite pieces of cooking equipment was a big blue, glazed ceramic mixing bowl. I don’t know where he bought it, but I always assumed it was secondhand—probably a throwaway from one of his restaurant customers—being it already showed wear with numerous chips around the edges which exposed the white ceramic. Not good enough for a diner or restaurant, but more than good enough for our eating establishment.

He would always invite me to help him mix the ingredients du jour. We would both get our hands into the bowl—my small hands squeezing around his large hands—and enjoy feeling the texture of the mix. We didn’t talk much. We didn’t have to. Our smiles said it all.

“So … let me understand this—you want to sneak back into a house which you couldn’t wait to leave, and even went so far as to have your name removed from the deed, all at the risk of being charged with trespassing to retrieve an old mixing bowl. Did I get it right, Ian?”

Her tone started out sarcastically, morphed into incredulity, and ended with her being totally pissed off. I was relieved she was on the other end of the phone.

“It’s not just some old mixing bowl. It was my father’s, and now it sits in the dark, behind a cupboard door, over a stove, in an empty house.” I was passionate in my defense and could hear my voice rise. But it wasn’t anger I was feeling. All I could think about was how my father came home late at night, and ate his dinner alone at the kitchen table by the dim solitary light that was built into the range hood, while the rest of us were comfortably asleep. Not once did I get out of bed to join him, or ask how his day went. Now I felt ashamed for being so selfish. All he ever wanted to do was make a little boy—his son—smile, and asked for nothing in return. Now that bowl was alone, and this was my opportunity to redeem myself; to make sure it never again sat in the dark alone. “I won’t let it happen again, Dori.”

“Let what happen again?” her tone becoming decidedly softer.

“Never mind. You wouldn’t understand. I’m going to get it.”

“Okay, Ian. But think about this. What if your brother makes an unannounced visit to the house and is standing there when you walk in? Do you have any idea what will happen next? Do you even care?”

I remained silent, and she filled the void.

“All hell will break loose, Ian. He’s crazy enough to have you arrested.” Her voice was starting to crack with tears.

“I’m not afraid of Hell, Dori. I’ve been there enough times in my life and made it through without the Devil even knowing I was there,” trying to make light of the situation. “Besides, it wouldn’t be the first time I was arrested.”

Her voice rose in anger: “You were a teenager then—a juvenile, goddamnit. Can’t you see the difference? Now you’re an adult where you can’t hide behind your age. You’ll have a real adult record.”

“You’re making more of this than it is, sweetheart. Nothing like that will remotely happen. I’ll be in and out before anyone knows I was even there.”

There was a very long pause. “Dori … are you still there?”

“Fine, Ian. Do what the fuck you want,” she said between full sobs. “You always do,” and hung up.

It was true what she said. All of it. Around the age of ten my maternal, bookie grandfather started to mentor me. He had no beef with the way my father was raising me, other than he thought I was growing up too soft. They both got along because he respected my father for his service in the war. My grandfather had fought with the British in WWI after emigrating from Czarist Russia and he, like my father, was a man of few words who always kept his own counsel. He thought of my father as more of a son, than Gertrude as a daughter, and made that known to both at every opportunity.

My grandfather taught me how to fight: how to survive on the streets by using my wits and my fists. At ten he also taught me and my best friend, Mikey, how to run numbers without getting caught. By the age of sixteen, Mikey and I were his collection agency. But it was my fighting and truancy which brought me into direct contact with the police on almost a daily basis.

My father didn’t like what I was doing; he had bigger plans and dreams for me, and tried to reason with me and my grandfather. I would just retort by saying I would be okay, that nothing bad would happen to me. My grandfather—who stood an inch taller than my father—would smile, put his hand on my father’s shoulder, and respond to him in his fading Russian accent, “Larry … I love the boy, your son, and I would never let anything bad happen to him. He’s a good boy. He just needs to learn the ways of the world. You and your brothers did growing up on the streets of Chicago, and you turned out to be a good man. So will he.”

Except I didn’t, and my father reacted. There were several incidents, at different intersections in our lives, and all had a profound and defining effect on the relationship between us. The first was when I was about fifteen. My father was now working for the post office and was able to sit with his family for dinner. Dinner, when made by my father, was one of the few times I would join him and Gertrude. This time, Henry was home from college for the weekend and we sat and ate as a family: my mother and Henry on one side of the table, and my father and I on the other. I sat to my father’s right.

That night I wasn’t particularly hungry. I was in a hurry, as I needed to attend to my errands, as my grandfather euphemistically referred to his illegal dealings. I finished only about half of my meal, then stood up. My father, without even looking at me, said in his firm but quiet way, “Sit down and finish your dinner, Ian. You’re not excused.”

“I’m not hungry, Dad, and I have some things to do. Thanks for the dinner.”

“I said sit down. I won’t tell you again.”

I sat back down, and then my mother chimed in with her two cents. “There are children in China who are starving, and they would love a meal like this.”

I was, and probably still am but to a lesser degree, a consummate smart-ass. I said, “Then send my meal to them.”

The back of my father’s right hand caught me squarely across my nose and sent me flying backward off my chair onto the floor. I had been hit in the face many times in fights, but I was always prepared. No hit to the face, before or after my father’s, ever caught me more by surprise, or caused such shock. He never struck Henry or me—ever. That task was always left to my mother, who prosecuted that endeavor with great skill and sadistic satisfaction. Henry sat there transfixed, utterly speechless at what had just happened. I have never asked him, but I have no doubt he felt some smug pleasure that his father’s golden boy had just been knocked on his ass—by his patron saint, no less.

My father turned slightly and raised himself from his seat, reached out his hand to me—which I took—and pulled me up from the floor. He handed me a napkin to wipe the blood from my nose. He then grabbed the chair and stood it upright. I was still reeling from the hit as my mother rushed over and ushered me to the sink. There, she soaked the napkin in cold water and directed me to hold it over my nose with my held tilted backward. I saw her shoot a sharp stare toward my father, but he wasn’t looking. He kept his head down and continued eating as if nothing had happened. It was then that the tug of war over to whom I held allegiance began.

My mother calmly said, “Ian, go to your room and lie down until the bleeding stops. You can finish your dinner later.”

“He’ll finish his dinner now, Gertrude,” my father said without looking up. “There’s only one dinnertime, and this is it. Ian, sit down and finish your dinner.”

There was a pause, a very long pause, to see which master I would serve. They were two people calling the same dog, waiting to see which one the dog would run to. I sat down.

My father looked at me and, with an even, low tone, spoke: “Don’t you ever speak to your mother in that manner again. Ever.”

He continued eating. I didn’t respond, because no response was necessary. Both Gertrude and I had our answers. She and father may not have had the most loving of relationships, but there was still a strong sense of generational honor—and Gertrude was still his wife.

My father and I never spoke of that incident until almost twenty years later—a year before he passed away—when I came to visit. I was sitting next to him on the couch, both of us watching a ball game. His hair had faded to auburn with streaks of gray, but his mustache remained fiery red. He was still a handsome guy. As much as I enjoyed being with him, I wasn’t smiling this time. He had a sixth sense that I wanted to say something. My father picked up the remote, pointed it at the TV to turn it off, and lit up another Lucky Strike.

“What’s on your mind, Ian?”

I thought about playing stupid and just saying “Nothing.” But I knew he wouldn’t believe it. Besides, the man deserved the truth, especially after all the hell I put him through when I was younger. “Do you remember when you hit me at the dinner table?”

He took a drag on his cigarette. “Yes, I remember. What about it?”

“Well … I just wanted to say that I’m sorry for the way I behaved and spoke to Mom, that’s all.” I was hoping for an apology in return—something that would show me how he felt about striking me.

Instead he put down his cigarette, looked straight into my eyes, and said, “It took you long enough, but that apology is owed to your mother, not me.” With that said, he turned away, picked up his cigarette, and clicked the TV back on. I should already have known how he felt, because of a discussion I overheard about fifteen years earlier. I just wasn’t as smart or insightful as I thought, and didn’t connect the dots.

The summer after I turned eighteen I was arrested for stealing a car. It wasn’t the first car I stole, nor was it the first time I disappointed my father, but it was the first as an adult rather than a juvenile. The judge gave me a choice of either four years in the military—at the height of the Vietnam war no less—or four years in the county prison. If I served honorably, my record would be expunged. If I went to prison, I would have a record forever. What a choice—either possibly dying in Vietnam, or living with a record. Both my father and grandfather—for whom I decided to no longer work, after an irate customer, during one of our collections, caught me in the head with a bat causing a two-inch gash which required a dozen or so stitches—convinced me the military was the better of two evils. I joined the Navy.

Before I acted on that decision, I came home earlier than usual for one of my father’s weekend dinners. I was always hungry. Running numbers, fighting and collecting bad debts from deadbeat customers will do that. My parents were in the kitchen and didn’t hear me come in. I could barely make out the conversation as they were talking softly, but something told me it was one which I didn’t want to walk into. I stayed in the dining room, but still in earshot for the last part of the exchange.

“When are you going to get rid of the blue mixing bowl, Larry? It’s so chipped, and it’s not like we can’t afford a better one. And speaking of damaged goods,” my mother sanctimoniously stated, “I can’t wait for Ian to leave. Perhaps then we’ll have some peace knowing that the next knock on the door won’t be the police.”

I peeked around the corner and saw my father turn toward my mother to address her question. “You’re right, Gertrude. This bowl is a piece of shit. But even damaged goods still have value and purpose.” His response was a culmination of all the death and misery he had seen and experienced in his life. Silence from my mother. My father had made his point, but I didn’t make the connection.

He reinforced those feelings later when he was the only one to write or visit me, while I was recuperating for four months in a Hawaiian hospital from wounds I suffered in ’Nam. My river boat was the sole target of an ambush while on a classified mission with two other boats. I was the only survivor. Not one call, letter, or visit from Gertrude or Henry; just my father. And yet, I still didn’t get it. God was I dense.

It wasn’t until some five years after his death that I told my mother, in one of our rare civil conversations, that I had apologized to my father. I then, finally and formally, apologized to her for my comment. She thanked me, but what she said next was yet another bat to my head. “I never saw your father cry, but he cried that night in bed. Your father never forgave himself for hitting you, Ian. As you know, your father was a man of few words, much to my chagrin. But I cannot tell you how many times, right up until his death, for no apparent reason at all, he would blurt out: ‘I should never have lost my temper and hit him, Gertrude. He didn’t deserve to be treated that way.’ Through all of the disappointments and heartaches, he always loved you, Ian. Always.” This time…this time, I finally got it. But I didn’t feel relieved or vindicated. I felt repentant.

Given the nature of my relationship with my mother, I have often wondered if she told me to assuage my torment, or to add salt to that open wound. I would like to think it was the former, but believe it was the latter.

A few days after that last stormy conversation with Dori—in spite of her protests, in spite of my attorney’s advice—I stopped at the old house. It was night, and there was a single light on in the living room. I walked straight to the kitchen, also illuminated, but only by the light under the range hood. I stopped for a moment, fully expecting to see my father eating his dinner. That should never have happened, I thought.

Over the stove, behind the cupboard door, sat the blue bowl. I needed something in which to carry it—something inconspicuous. I spotted a large brown bag—the kind the grocery stores still offer as a choice between paper or plastic—and promptly put the bowl into it. Then I threw in a couple of other items and quickly left, hoping none of the spying neighbors had ratted me out to my brother or the police. Driving to my new apartment I felt relief and satisfaction—like someone who just rescued a hostage without being spotted or apprehended.

I parked the car and opened the passenger door to retrieve my backpack and the brown bag lying on the front seat. After slinging the backpack over my left shoulder, I grabbed the bag with my right hand. That blue bowl, that old blue bowl with the weight of all of its memories, was too much for the bag. Before I could place it on the ground so I could shut the door there was a tear, a clumsy attempt to grab the bag, and then a sickening crack as it hit the sidewalk. I wasn’t sure if the sound came from my heart or the bowl. I stood there for a few moments in somber shock, trying to comprehend what had just happened. Then I cradled the bag, now full of my shattered plans, in my arms, and raced up the stairs to my second floor apartment, as if it were a dying patient I was attempting to get into the emergency room before it expired.

Five pieces. All clean breaks. I spread out a dish towel and carefully placed the pieces onto it. I stared at it, willing it to heal itself. What have I done?

I walked to the den, sat down in my lounger, lit a cigarette. It was about the time I usually called Dori, but we hadn’t spoken, or even texted each other, since that last tearful call two days earlier. Do I tell her what really happened, or just put on a happy face and say nothing? I decided I had to tell her the truth. She would find out sooner rather than later. Besides, Dori had become my confidante, and I didn’t want the relationship to be encumbered by lies or omissions of the truth. I had to walk into that minefield.

“Hi, Ian. Funny you should call.”

“Why’s that?”

“Because I was about to call you. I wanted to apologize for the way I went off on you the last call.”

“No apology necessary, sweetheart. Everything you said was true. I’m sorry I was such a rock head. But thanks just the same.”

“How was your day?”

“Work was fine, but I need to tell you what happened after work.” Stepping into the unknown, I recounted all of it. “I never should have put the bowl on the bottom. That was stupid.”

I hoped to garner some sympathy. Instead, there was dead silence on Dori’s end. I was now in the center of that field of explosives, and saw no clear path by which to extricate myself safely. When Dori finally spoke, the whole field started to explode around me. She made no attempt to hide her anger.

“No, Ian … stupid was you entering the house. The bowl didn’t break because of your stupidity. It broke because of your arrogance.”

“What the hell is that supposed to mean?”

“It means just what I said, you arrogant, selfish, son of a bitch. All you thought of was yourself. You really didn’t give a shit about the bowl, or you would have taken better care to make sure it was protected. And you certainly didn’t consider my feelings. You just wanted to stick your finger in your brother’s and mother’s collective eye to say, ‘See? I can enter the house when I damn well feel like it and take what I want.’”

“That’s not.…”

“Shut the hell up, Ian. I’m not through.”

I felt like I was back in ’Nam, in the middle of a horrific firefight with no ammunition. That minefield was tearing me apart. Why on earth did I ever enter it?

“I’ll give you credit, Ian. You’ve been in some tough spots in your life and always managed to come through on the plus side. But that didn’t make you stronger, or more humble, confident, or thankful. It made you cynical and arrogant. What is it you always said? ‘I’ve done so much, with so little, for so long, that I now believe I can do the impossible with absolutely nothing, forever.’ I used to think that was cute and clever, and, in some way, I admired you for your strength of character and tenacity. Now I see it for what it really is, for what you really are—a spoiled, arrogant child who can’t stand to have things not go his way. I know you had to repeat that mantra to keep you going, but you’ve said that bullshit line for so long, you actually started to believe it! And that’s what really scares the shit out of me.”

The tears started to come through the phone again. “I thought I was starting to really know you. But I now realize that’s not possible, because you don’t even know yourself. Knowing you is like attempting to put your arms around fog. Get a grip, Ian. And when you can admit what you’ve really become, then maybe, just maybe, you and I can have a relationship that’s built on something more stable than delusions of grandeur. I gotta go.” She hung up.

Dori was right…again. I still wasn’t connecting the dots. Had the bowl meant that much to me, I not only would have taken greater care when I transported it, I would have taken it when I moved. But the bowl did have meaning to me; it connected me to my father—the one parent who loved me unconditionally. I did the right thing, but for the wrong reason. It wasn’t the first time.

I volunteered—yes volunteered—for combat duty in Vietnam, even though I had already graduated from Submarine School and was attending the Navy’s advanced communication courses. And not for some patriotic reason, but because Mikey—my best friend and accomplice in my youthful, nefarious enterprises—who enlisted as a Marine, was killed halfway through his Vietnam tour. I wanted to avenge his death. After I recovered from my wounds, I served five more years on submarines. Again, not because I wanted to serve my country or because I had a great love of working in the depths of the sea, but because I was doing something most people didn’t have the balls to do, and it also gave me the time I needed to hide from the world and recover emotionally from ’Nam.

The right things, for the wrong reasons. The story of my life. Dori knew what I had done, but she didn’t know why I had done them. She was on the cusp of understanding it all, and that scared the hell out of me.

Several days after that last call from Dori, I confided to a friend at work all that had gone down. Within earshot was a young girl working part-time while she attended graduate school. Though she had been there about a week, I had never made the attempt to introduce myself—a hangover habit from my days in the Navy, especially Vietnam.

While on a smoke break a couple of days later, she came over and introduced herself to me, and asked if we could talk. I was expecting her to ask me about work and how she could do her job better. Instead, she hesitated for a moment and then sheepishly said, “I overheard your conversation with Alex.”

I stared at her and remained silent, not knowing where this conversation was going. She continued: “I studied in Japan during my junior year in college, and became fascinated by the people, their history and culture. My graduate work is an extension of that experience.”

“That’s interesting, Bailey, and I wish you well in your studies. But what does any of that have to do with me?”

Bailey responded timidly, hearing the less-than-enthusiastic tone of my voice: “I believe I have a solution for your bowl.”

“How’s that?”

“Have you ever heard of kintsugi?”

“No. What is it?”

“It’s the Japanese art of fixing broken pottery with lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum.”

“Terrific. Let me know where I can get my hands on some of those materials. For me, it’s going to be super glue.”

“But people use glue to hide the damage.”

“Precisely. Who wants to see the cracks?”

Bailey explained, “The philosophy behind kintsugi treats breakage and repair as part of the history of an object—something to celebrate, rather than something to disguise. An art form, if you like. The life of an object is extended by transforming it, rather than allowing its service to end just because it’s become damaged goods.”

Damaged goods. That caught my full attention. Perhaps my father was using kintsugi intuitively: attempting to extend my life by transforming me into someone of value and purpose—not by disguising my flaws, but by having me recognize them, and understand that they, too, are a part of my history.

“Thanks for the advice, Bailey. I’ll give it serious consideration. Really.”

“You’re welcome. The bowl apparently means a great deal to you, and it deserves a better place than stuck away in a cupboard to be forgotten. I may be going out on a limb, Ian, but my guess is the bowl isn’t the only thing you want to repair.”

I could feel a small smile form on my face. “You’re a smart, intuitive young lady and wise beyond your years.” I paused briefly, then said, “We should be getting back in before they start to miss us.”

As we reached the door to our office, I stopped and turned to Bailey. “I apologize for not introducing myself earlier. Just an old, outdated, and stupid habit. I’m delighted we had the chance to chat.”

Several months after I moved into my apartment, I was finally unpacked and had my new place furnished and decorated. It was time to open the doors to my friends for an inaugural dinner. The apartment was ideal. I occupied the second and third floors of a completely renovated and refurbished, three-story, Victorian mansion located in what they now call The Historic District of the city. It had all the room and amenities I ever wanted. More so, it was the first place I could really call home since my divorce years earlier.

The apartment wasn’t the only thing that went through transformation. Bailey’s comment continued to gnaw at me like a river slowly, relentlessly, carving out a canyon. I still believed in my mantra, and came to the conclusion there was absolutely no reason I couldn’t transform myself. My life, my relationship with my friends and my children—and especially with Dori—depended upon it, now. I didn’t have the luxury of several thousand years. My relationship with Henry and Gertrude? Well, that would have to wait for another epiphany.

After about an hour of socializing, I ushered everyone into the dining room, which I had kept hidden behind closed doors until that moment. The spacious room with its ornate, but tasteful, woodwork was the crown jewel of the apartment. Its high ceiling was adorned by a Victorian-style chandelier in the center. Under it sat a period-appropriate cherry dining room set I found at an estate sale, which rested regally on a lush, pale oriental rug with a simple, graceful, multi-color design. The centerpiece of the room was a stately fireplace bound in exquisitely carved mahogany, capped with two mantels which framed a mirror.

As the guests were about to be seated, Suzanne—the better half of a couple I had known since before my divorce—looked at the mantel above the mirror and said with childlike wonderment, “This blue bowel, Ian. It’s so unique and beautiful. Simply elegant. I have never seen a piece of pottery decorated in such fashion. Where on earth did you find it?”

I glanced over at Dori, who gave me her crooked smile, and nodded her head, as if to say: Go ahead, Ian. Tell the story. You’ve earned it.

I put my drink down, and pushed my hands into the pockets of my pants—a tell of mine since I was a kid, when I was about to share some secret. I glanced down reflectively, then raised my head and smiled at Suzanne. “Have you ever heard of kintsugi?”

BIO

I served seven years in the Navy, which included a combat tour in Vietnam on river boats, and five years aboard nuclear-powered, Fast Attack submarines. At 65, my life is quieter now: anything would be quieter than my military venture. I am a member of the Pagoda Writers Group, and find that I’ve been devoting more and more time to my writing. I write under the pen name L.D. Zane.

I served seven years in the Navy, which included a combat tour in Vietnam on river boats, and five years aboard nuclear-powered, Fast Attack submarines. At 65, my life is quieter now: anything would be quieter than my military venture. I am a member of the Pagoda Writers Group, and find that I’ve been devoting more and more time to my writing. I write under the pen name L.D. Zane.

Stories published: Red Fez, Solomon’s Shadow, February 2015; Indiana Voice Journal, One Out of Three, March 2015; Red Fez, River of Revenge, April 2015, Remarkable Doorways Online Literary Magazine, The Box, May 2015, and The Writing Disorder, Kintsugi, June 2015.

Ron Yates received his MFA from Queens University of Charlotte, where he worked with many fine writers and teachers and completed a novel entitled BEN STEMPTON’S BOY, set in the rural south of the early 1970’s. Yates has recently completed a short fiction collection, MAKE IT RIGHT AND OTHER STORIES, a work driven by two key components of his aesthetic: a desire to create crisp, character-driven prose and to evoke place in a way that furnishes and textures the fictional dream.

Ron Yates received his MFA from Queens University of Charlotte, where he worked with many fine writers and teachers and completed a novel entitled BEN STEMPTON’S BOY, set in the rural south of the early 1970’s. Yates has recently completed a short fiction collection, MAKE IT RIGHT AND OTHER STORIES, a work driven by two key components of his aesthetic: a desire to create crisp, character-driven prose and to evoke place in a way that furnishes and textures the fictional dream.

Emily Strauss has an M.A. in English, but is self-taught in poetry, which she has written since college. Over 250 of her poems appear in a wide variety of online venues and in anthologies in the U.S. and abroad. The natural world is generally her framework; she also considers the stories of people and places around her and personal histories. She is a semi-retired teacher living in California.

Emily Strauss has an M.A. in English, but is self-taught in poetry, which she has written since college. Over 250 of her poems appear in a wide variety of online venues and in anthologies in the U.S. and abroad. The natural world is generally her framework; she also considers the stories of people and places around her and personal histories. She is a semi-retired teacher living in California.

Tim W. Boiteau has published stories in a number of journals, including Every Day Fiction, Write Room, Kasma Magazine, and LampLight. He was a finalist in Glimmer Train’s 2013 Fiction Open contest. He is currently finishing a PhD in Experimental Psychology at the University of South Carolina.

Tim W. Boiteau has published stories in a number of journals, including Every Day Fiction, Write Room, Kasma Magazine, and LampLight. He was a finalist in Glimmer Train’s 2013 Fiction Open contest. He is currently finishing a PhD in Experimental Psychology at the University of South Carolina.

Sarah Sarai’s short stories are in Gravel, Devil’s Lake, Storyglossia, Homestead Review, Fairy Tale Review, Weber Studies, Tampa Review, South Dakota Review, and other journals; her story, “The Young Orator,” was published as a chapbook and e-book by Winged City Chaps, Her poetry collection, The Future Is Happy, was published by BlazeVOX; her poems are in journals including Ascent, Boston Review, Pool Poetry, Thrush, Yew, and Threepenny Review. Links to her book reviews, poems, and stories are on her blog, My 3,000 Loving Arms. Sarah is a contributing editor for The Writing Disorder and a fiction reader at Ping Pong Literary Journal published by the Henry Miller Library. She attended grammar school and junior and senior high in the San Fernando Valley. She now lives in New York.

Sarah Sarai’s short stories are in Gravel, Devil’s Lake, Storyglossia, Homestead Review, Fairy Tale Review, Weber Studies, Tampa Review, South Dakota Review, and other journals; her story, “The Young Orator,” was published as a chapbook and e-book by Winged City Chaps, Her poetry collection, The Future Is Happy, was published by BlazeVOX; her poems are in journals including Ascent, Boston Review, Pool Poetry, Thrush, Yew, and Threepenny Review. Links to her book reviews, poems, and stories are on her blog, My 3,000 Loving Arms. Sarah is a contributing editor for The Writing Disorder and a fiction reader at Ping Pong Literary Journal published by the Henry Miller Library. She attended grammar school and junior and senior high in the San Fernando Valley. She now lives in New York.

Audrey Iredale lives in the beautiful Sonoran Desert city of Phoenix, Arizona, with her husband and three precious rescued kitties. They have three daughters and two grandchildren. She studied Language Arts at community colleges in California and Arizona and graduated Phi Theta Kappa with a 4.0 GPA. She has been writing and singing since childhood and works in technology manufacturing.

Audrey Iredale lives in the beautiful Sonoran Desert city of Phoenix, Arizona, with her husband and three precious rescued kitties. They have three daughters and two grandchildren. She studied Language Arts at community colleges in California and Arizona and graduated Phi Theta Kappa with a 4.0 GPA. She has been writing and singing since childhood and works in technology manufacturing.

Jon Riccio studied viola performance at Oberlin College and the Cleveland Institute of Music. A recent Pushcart nominee, his work has appeared or is forthcoming in Paper Nautilus, Qwerty,Redivider, CutBank Online, Waxwing and Switchback, among others. An MFA candidate at the University of Arizona, he resides in Tucson.

Jon Riccio studied viola performance at Oberlin College and the Cleveland Institute of Music. A recent Pushcart nominee, his work has appeared or is forthcoming in Paper Nautilus, Qwerty,Redivider, CutBank Online, Waxwing and Switchback, among others. An MFA candidate at the University of Arizona, he resides in Tucson.

Michael Davis’ short fiction has appeared in Descant, The San Joaquin Review, The Jabberwock Review, The Black Mountain Review, Eclipse, Cottonwood, The Mid-American Review, Full Circle, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Georgia Review, Storyglossia, The Chicago Quarterly Review, Willow Springs, The Normal School, Arcana, The Superstition Review, The New Ohio Review, The Painted Bride Quarterly, The Atticus Review, Isthmus, the Earlyworks Press Short Story Anthology, Redline, and Small Print Magazine. His collection of stories, Gravity, was published by Carnegie Mellon UP in 2009. He has an MFA in fiction writing from the University of Montana and a PhD in English from Western Michigan University. He lives in Bangkok where he is a lecturer in English at Stamford International University.

Michael Davis’ short fiction has appeared in Descant, The San Joaquin Review, The Jabberwock Review, The Black Mountain Review, Eclipse, Cottonwood, The Mid-American Review, Full Circle, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Georgia Review, Storyglossia, The Chicago Quarterly Review, Willow Springs, The Normal School, Arcana, The Superstition Review, The New Ohio Review, The Painted Bride Quarterly, The Atticus Review, Isthmus, the Earlyworks Press Short Story Anthology, Redline, and Small Print Magazine. His collection of stories, Gravity, was published by Carnegie Mellon UP in 2009. He has an MFA in fiction writing from the University of Montana and a PhD in English from Western Michigan University. He lives in Bangkok where he is a lecturer in English at Stamford International University.

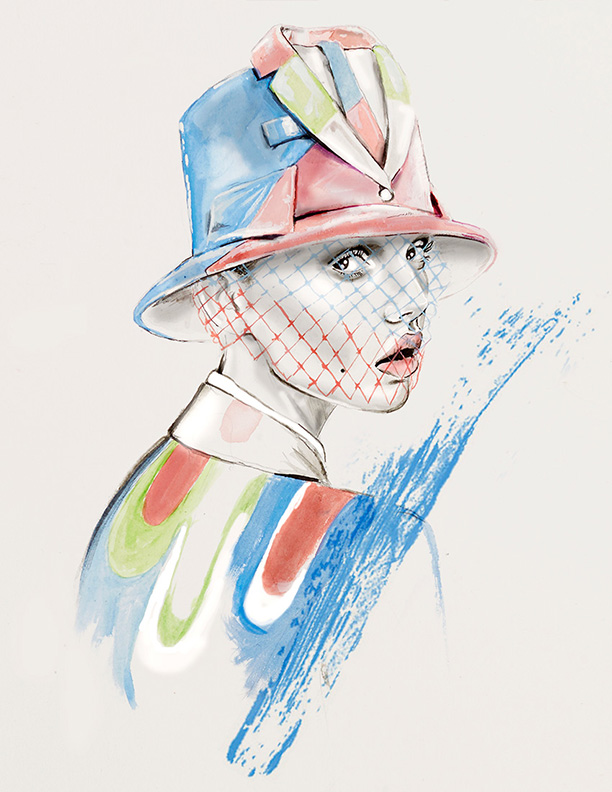

Born in Canada and bred in the U.S., Allen Forrest has worked in many mediums: computer graphics, theater, digital music, film, video, drawing and painting. Allen studied acting in the Columbia Pictures Talent Program in Los Angeles and digital media in art and design at Bellevue College (receiving degrees in Web Multimedia Authoring and Digital Video Production.) He currently works in the Vancouver, Canada, as a graphic artist and painter. He is the winner of the Leslie Jacoby Honor for Art at San Jose State University’s Reed Magazine and his Bel Red painting series is part of the Bellevue College Foundation’s permanent art collection. Forrest’s expressive drawing and painting style is a mix of avant-garde expressionism and post-Impressionist elements reminiscent of van Gogh, creating emotion on canvas.

Born in Canada and bred in the U.S., Allen Forrest has worked in many mediums: computer graphics, theater, digital music, film, video, drawing and painting. Allen studied acting in the Columbia Pictures Talent Program in Los Angeles and digital media in art and design at Bellevue College (receiving degrees in Web Multimedia Authoring and Digital Video Production.) He currently works in the Vancouver, Canada, as a graphic artist and painter. He is the winner of the Leslie Jacoby Honor for Art at San Jose State University’s Reed Magazine and his Bel Red painting series is part of the Bellevue College Foundation’s permanent art collection. Forrest’s expressive drawing and painting style is a mix of avant-garde expressionism and post-Impressionist elements reminiscent of van Gogh, creating emotion on canvas.

Paul Garson lives and writes in Los Angeles, his articles regularly appearing in a variety of national and international periodicals. A graduate of the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars and USC Media Program, he has taught university composition and writing courses and served as staff Editor at several motorsport consumer magazines as well as penned two produced screenplays. Many of his features include his own photography, while his current book publications relate to his “photo-archeological” efforts relating to the history of WWII in Europe, through rare original photos collected from more than 20 countries. Links to the books can be found on Amazon.com. More info at

Paul Garson lives and writes in Los Angeles, his articles regularly appearing in a variety of national and international periodicals. A graduate of the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars and USC Media Program, he has taught university composition and writing courses and served as staff Editor at several motorsport consumer magazines as well as penned two produced screenplays. Many of his features include his own photography, while his current book publications relate to his “photo-archeological” efforts relating to the history of WWII in Europe, through rare original photos collected from more than 20 countries. Links to the books can be found on Amazon.com. More info at

Sandra Rokoff-Lizut, retired educator and children’s book author (published by Macmillan, Holt Reinhart & Winston, and Hallmark Inc.), is currently both a printmaker and poet. She is a member of Oregon Poetry Association and first place award winner in their Spring 2014 contest, Mary’s Peak Poets, Poetic License, Gertrude’s, and a weekly writing salon. Rokoff-Lizut volunteers by teaching poetry to middle-schoolers at the Boys and Girls Club in Corvallis. She also studied poetry through OSU as well as at Sitka and Centrum. Previous publications include Illya’s Honey, The Bicycle Review, Wilderness House Review, The Penwood Review, Wild Goose Poetry Review and Verseweavers.

Sandra Rokoff-Lizut, retired educator and children’s book author (published by Macmillan, Holt Reinhart & Winston, and Hallmark Inc.), is currently both a printmaker and poet. She is a member of Oregon Poetry Association and first place award winner in their Spring 2014 contest, Mary’s Peak Poets, Poetic License, Gertrude’s, and a weekly writing salon. Rokoff-Lizut volunteers by teaching poetry to middle-schoolers at the Boys and Girls Club in Corvallis. She also studied poetry through OSU as well as at Sitka and Centrum. Previous publications include Illya’s Honey, The Bicycle Review, Wilderness House Review, The Penwood Review, Wild Goose Poetry Review and Verseweavers.

A graduate of Syracuse University School of Art and New York University, I have been a textile, apparel and home products designer for three decades, working in the New York and Los Angeles garment and design districts. I began painting canvases in 2004 and have experimented with various styles. I started with a series of large expressionist botanicals and have since moved on to more illustrative studies of mid century modern themes. As a long time collector of Eames Era furnishings, I find the subjects fun and inspiring. I like to add my own twist to the sometimes stark Eames elements by posing pets in the settings. I am also intrigued by the futuristic space age themes from the period, and like to add mystery and humor to my works.

A graduate of Syracuse University School of Art and New York University, I have been a textile, apparel and home products designer for three decades, working in the New York and Los Angeles garment and design districts. I began painting canvases in 2004 and have experimented with various styles. I started with a series of large expressionist botanicals and have since moved on to more illustrative studies of mid century modern themes. As a long time collector of Eames Era furnishings, I find the subjects fun and inspiring. I like to add my own twist to the sometimes stark Eames elements by posing pets in the settings. I am also intrigued by the futuristic space age themes from the period, and like to add mystery and humor to my works.

Walter B. Thompson is a native of Nashville, Tennessee. His work has previously appeared in The Bicycle Review, Carolina Quarterly and elsewhere. He received his M.F.A. from the University of Wisconsin, where he is currently the Halls Emerging Artist Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing.

Walter B. Thompson is a native of Nashville, Tennessee. His work has previously appeared in The Bicycle Review, Carolina Quarterly and elsewhere. He received his M.F.A. from the University of Wisconsin, where he is currently the Halls Emerging Artist Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing.

Anna Boorstin grew up riding horses, playing board games and reading. After attending Yale, she worked as a sound editor on films such as Real Genius and Clue. She raised three children and is happy to have (finally) found her way back to writing. Her story, Paper Lantern, made the Top 25 of Glimmer Train’s August 2013 Award for New Writers and was recently published in december magazine. Her Lizard Story was in Fiddleblack. She also blogs at

Anna Boorstin grew up riding horses, playing board games and reading. After attending Yale, she worked as a sound editor on films such as Real Genius and Clue. She raised three children and is happy to have (finally) found her way back to writing. Her story, Paper Lantern, made the Top 25 of Glimmer Train’s August 2013 Award for New Writers and was recently published in december magazine. Her Lizard Story was in Fiddleblack. She also blogs at

Jon Fried has published short fiction in Third Bed, Eclectica, Bartleby Snopes, Beehive, Pierogi Press, Pindeledyboz, Map Literary, Scissors & Spackle, Lamination Colony, New Works Review, The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review and Prick of the Spindle (soon) and other literary journals and e-zines, as well as songs he has written for a rock band he co-founded called the Cucumbers, which has released several recordings. He is working on a collection of stories about work called Transcendent Guide to Corporate America and a series of novels based on some colorful characters in his family tree. A Little Bit Closer to Water is set several years ago, so some of the media references are a little out of date.

Jon Fried has published short fiction in Third Bed, Eclectica, Bartleby Snopes, Beehive, Pierogi Press, Pindeledyboz, Map Literary, Scissors & Spackle, Lamination Colony, New Works Review, The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review and Prick of the Spindle (soon) and other literary journals and e-zines, as well as songs he has written for a rock band he co-founded called the Cucumbers, which has released several recordings. He is working on a collection of stories about work called Transcendent Guide to Corporate America and a series of novels based on some colorful characters in his family tree. A Little Bit Closer to Water is set several years ago, so some of the media references are a little out of date.

Evelyn Levine is a senior English major at Whitman College. A native of San Francisco, she hopes to one day be able to afford the rent. Evelyn enjoys spending time with her vocal cat Alan, baking for friends and family, learning Tai Chi, and playing the mandolin (albeit unskillfully). This is Evelyn’s first fiction publication.

Evelyn Levine is a senior English major at Whitman College. A native of San Francisco, she hopes to one day be able to afford the rent. Evelyn enjoys spending time with her vocal cat Alan, baking for friends and family, learning Tai Chi, and playing the mandolin (albeit unskillfully). This is Evelyn’s first fiction publication.

A. A. Weiss grew up in Maine and works as a foreign language teacher after having lived in Ecuador, Mexico and Moldova, where he served in the U. S. Peace Corps from 2006-2008. His writing has appeared in Hippocampus, 1966, Drunk Monkeys, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and Pure Slush, among others, and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He lives in New York City. Website:

A. A. Weiss grew up in Maine and works as a foreign language teacher after having lived in Ecuador, Mexico and Moldova, where he served in the U. S. Peace Corps from 2006-2008. His writing has appeared in Hippocampus, 1966, Drunk Monkeys, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and Pure Slush, among others, and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He lives in New York City. Website: