TOM TURKEY

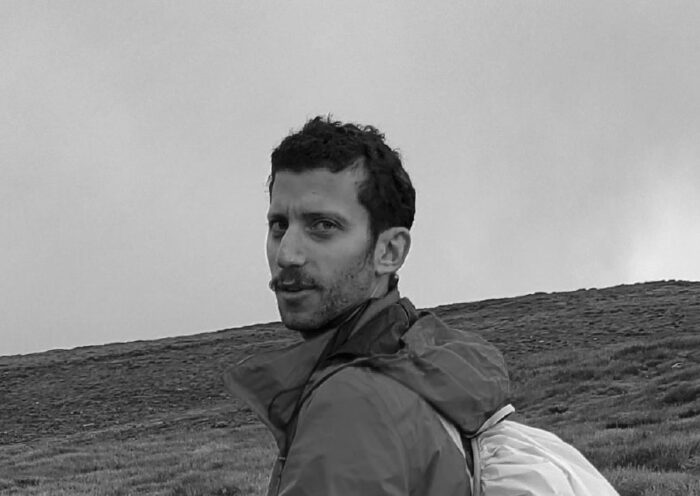

by Justin Meckes

Nov. 21

Martin Reinhold was stoking the flames inside his brick fireplace when he heard a knock at the front door. The dark-haired, middle-aged man listened briefly, waiting to see if anyone else was going to answer it. When he heard nothing but the crackle and pop of the flames before him, he sighed and put the iron poker back on the stand.

Martin was greeted by

his mother, who was holding her arms out, exclaiming, “Oh, Martin!”

“Hi, Mom.”

Grandma Reinhold was an older woman with hair dyed so

black that it ceased to reflect light. She was wearing a velveteen

tracksuit—this one was fuchsia with white piping—and

a jacket with a faux fur lining. Her husband was a spry gentleman with a

full head of salt and pepper hair that his son

was destined to inherit.

The older man removed his beige Member’s Only jacket, saying, “Did you know the house next door is for sale, son?”

“I did,” answered Martin as he took the coat. “Scott got a new

job.”

“Where?”

“Florida.”

Martin began wheeling his parent’s luggage into the foyer.

“We should move to Florida, Henry,” said Grandma

Reinhold. She had already entered the living

room but turned to gauge her husband’s response.

Grandpa Reinhold had learned to tune out his spouse’s

nonsensical whims long ago, but this time

there was a legitimate reason. He was sniffing the air like a canine, pausing,

then sniffing at it again, saying, “Is something burning?”

Martin narrowed his eyes. “Burning?”

“Are you cooking something?” asked Grandma Reinhold as

she fluffed the hair on the back of her head, which the headrest of a Buick

Regal had flattened during a nine-hour drive.

“No,” answered Martin just before smoke began rising from the living room’s oriental rug. Eking out a small yelp, Martin darted toward

the fireplace only to find a small blaze.

Taking what was readily available—specifically, his father’s Member’s Only

jacket—the middle-aged man attempted to beat

the fire back by flogging it with the coat.

Grandpa Reinhold yelled, “Hey, that’s my jacket!”

Martin didn’t respond because he’d succeeded in only fanning the flames into a full-on conflagration. When Martin’s wife Cheryl came down the stairs to learn what the commotion was about, she exclaimed, “Oh my God!”

Grandma Reinhold waved and said, “Hi, dear.”

Cheryl ignored her mother-in-law and hurried to the

kitchen as the smoke detector started

blaring.

As Martin was

working doggedly to smother the flames, the rug and part of his arm were splashed with

water. He turned to see Cheryl standing behind him with an empty mop bucket.

The short, dark-haired woman was wearing

workout gear and a sweatshirt. She used one hand to tuck her hair behind an ear before saying, “What the hell is going on down here?”

While Martin got to his

feet, Grandpa Reinhold bent down and took ahold of his coat. “Would you

just look at this? Ruined. Absolutely ruined.”

“What happened?” Cheryl continued.

“I don’t know,” said

Martin.

Cheryl rolled her eyes as she moved away, saying, “I

liked that rug.”

Calling after her, Martin’s mother said, “It was nice,

wasn’t it?” Then she glanced into the fireplace and commented to Martin, saying, “The

fire’s nice too. Did you build it for us?”

Martin ignored her and looked down at his wet sleeve.

“I’m gonna go change my shirt.”

“She splashed you pretty good, didn’t she?” said Grandpa Reinhold, chortling as his son made

his way to the stairs.

Grandma Reinhold muttered, “Well, he was in the way.”

After Martin walked past his daughter’s room, he stopped,

took a step back, and knocked. “Your grandparents are here, Sarah.” The teenager was still upset at her father because he

hadn’t let her go out; instead, he’d forced her to be present when his parent’s arrived.

So, there was no response.

Martin crossed the hall and knocked on another door.

“Will? Your grandparents are here.”

“All right!”

The eight-year-old threw

open his door and blew past his father.

Martin watched his son hurry downstairs, shouting,

“Grandma! Grandpa!”

Smiling to himself, Martin continued making his way to the master bedroom. He unbuttoned his damp flannel shirt while

looking for another one to put on. He chose a short-sleeve Oxford and a sweater

that paired just as well

with his khakis. Martin’s casual attire was about as stylish as the gray suits that had become so much a part of his routine at the

accounting firm where he spent fifty hours per

week, crunching numbers and poring over tax documents.

He was already dreading Monday morning, but, at least, this was a holiday week.

After changing, Martin made his way back downstairs,

where he stood alongside his frowning father, who was surveying the damage to the rug.

Turning to his dad, he

said, “So, how was the trip?”

“Traffic was hell,” answered Grandpa Reinhold as he began

moving toward the kitchen. “And my tuchus is killing me.”

Sitting at the bar, Will started to giggle, having heard his grandfather say tuchus.

Martin noted that Cheryl

had already poured his mother a glass of wine as

he said, “Sarah should be downstairs any minute.”

Stepping back toward the living room, he cried out, “Sarah! Your grandparents would like to see you!”

A few minutes later, he

and everyone else heard a door open and then slammed shut. A young woman

with a brown ponytail and jeans that were too tight—at least, in her father’s

estimation—hurried down the steps before rounding the corner to

find everyone waiting. She put on a smile when she

entered the room, then said, “Hi, Grandma!

Grandpa!”

She hugged them both.

After that, she turned to her father and said, “Can I go

out, now?”

Nov. 22

Cheryl was usually in a bad mood when his parents were in

town, so Martin left for the office early. And

whereas he wasn’t sure why his wife and his parents

didn’t get along, he felt it was their

problem. The grumpy middle-aged man was

searching through the local radio stations as

he drove. When he came upon one playing a Christmas

tune, he stopped. Isn’t it a

little early for Christmas songs? Martin shook his head as he slowed in front of a stoplight. Christmas seemed to be starting earlier and

earlier each year, and it was beyond him as to why.

Furrowing his brow, Martin considered the fact that

Christmas had even begun to encroach on Halloween. The middle-aged man sighed, thinking that the older his children became, the

more and more Dec. 25th had started to feel

like any other day. At least with Thanksgiving, he could gorge on food and not

catch flack for it. At the dinner table, recently, Cheryl had begun

asking if he hadn’t had enough or even tried reminding him that he was trying

to lose weight. God, he hated that. Martin had what

he thought was an appropriate amount of love handles and tummy for a man his age—no matter what she or anyone else had to

say about it. And maybe, just maybe, he would

exercise more if he was rewarded with a bit of

coitus from time to time. Did you ever think of that, honey? And yes, he meant it that formally. It wasn’t sex anymore—not

with Cheryl. It had become something… well,

mechanical—when it happened at all.

Sitting at a red

light, Martin mouthed the words, “Aren’t you trying to lose a little weight?”

After rolling his eyes, he looked over at the car beside him: A big woman and an older man with a bristly gray mustache were staring back at him, so he pretended he was on the phone and kept talking to himself until the light turned green, and he put his foot to the floor.

#

Once inside his building, Martin nodded at a ponderous security

guard before making his way to the elevator,

and then up to his floor. If he were the first

to arrive at the offices of Gruber & McClane, he’d have a chance to make

the coffee in the break room, which was his preference since it often tasted

like little more than dishwater when one of his

coworkers prepared it. Unfortunately, this morning, when Martin turned the corner into the kitchenette, he

found Jim spooning grounds into a filter. Jim

was a stout, older man with a bald spot, a fondness for bowties—today’s, was a

very dapper red and navy stripe—and not the

slightest clue how to make a decent cup of coffee.

Martin sunk briefly before noticing that someone had hung a cartoon turkey on the refrigerator. Entering the break room with his briefcase in hand, he said, “At least we’re on the right holiday around here.”

Startled, Jim turned swiftly. “Oh, hey, Martin.”

Martin pointed at the fridge. “I heard Christmas music on

the radio on the way in. Can you believe that?”

Jim glanced over at the clipart turkey as Martin reached for a mug, saying, “Let me ask you

something: When was the last time you got anything you actually wanted for

Christmas?”

Chuckling, Chuck said,

“That might be too big of a question for this early in the morning. What I

actually wanted? Geez… Do any of us know what we actually want? I mean, I

haven’t even had my first cup of coffee yet.”

Reaching for the pot, Jim poured some dishwater into a mug he’d already filled

halfway with creamer.

Seeing just how weak the so-called coffee was, Martin

decided to put his cup back in the cabinet before taking a seat at a nearby table. “I didn’t mean it

philosophically, Jim. I meant what have you

gotten that you really wanted—as in another dive trip instead of a 6-pack of crew

length socks.”

“Well,” said Jim as he sipped dishwater from a mug. “Patty and I buy all of our own Christmas gifts.”

Martin appeared incredulous. “How’d you finagle that?”

Jim pulled out a chair and

took a seat, saying, “We’ve been doing it for

years. I buy what I want. She buys what she wants. Then we wrap ‘em up for one

another.”

“That’s genius.”

“I know.”

“You didn’t come up with it, did you?”

“Technically, Patty did. And I think she was like you—tired

of getting socks.”

“You gave your wife socks for Christmas?”

Jim shrugged. “They were made of alpaca wool.”

Martin crossed his legs as another coworker walked into the kitchenette. She was a petite,

blonde-haired woman with a bob haircut, wearing a dark pantsuit.

“Good morning, gentleman.”

Martin nodded as Jim continued,

saying, “What are you doing for Thanksgiving,

Maggie?”

Maggie sighed. “Oh,

well, apparently, I’m one of those idiots who travels the day before

Thanksgiving.”

“Wow,” said Martin.

“I know. I know, but it’s for my parents, and I’m saving

my days off.”

“For what?” asked Jim as he sipped his coffee.

“I don’t know. I’m

thinking of going somewhere this summer.”

Martin furrowed his brow. “Where?”

“Iceland? Greenland? Some land,” said Maggie as she

poured coffee into her mug.

“Well, aren’t you the adventurous one,” said Jim.

“I didn’t say I’d booked the ticket yet,” said Maggie. Then she

turned and said, “Oh, look! Somebody hung a turkey on the fridge. Isn’t that

nice?”

“It’ll look a whole lot better on my plate come

Thursday,” quipped Jim.

After taking a sip of her coffee, Maggie made a face.

“Ugh. Who the hell made this swill?”

Martin pointed at Jim.

#

As Martin approached the front door, he noticed a realtor

walking out of his neighbor’s house alongside a young couple. A little girl of three or four

was holding her mother’s hand. The scene made Martin feel a little nostalgic. Sarah had been about that age when he and Cheryl had

bought their home, and it—well, it seemed like yesterday. Now, she was all

grown up and applying to college, early admission, with a good chance of

getting into some top-notch schools, which was

going to cost him an absolute fortune. Watching the child being loaded into a silver minivan, Martin recalled that at one

time, he’d been Sarah’s favorite person in the world and that Cheryl had been jealous. He’d, ultimately, been able

to assure his wife that Sarah loved them equally, which was true even if he was

the definitive favorite.

Martin walked inside the house only to be welcomed by his

wife’s shouting. She and their son were having it out upstairs.

Meanwhile, his parents were sitting quietly in the living room. His mother was reading a

magazine as his father watched ESPN.

Still in the foyer, Martin cried out, “Hey! What’s going

on up there?”

Cheryl came downstairs a moment later, saying, “I’m sick

and tired of telling him to clean that room.”

Martin shook his head and put his hands on his

wife’s shoulders, saying, “I keep telling you to let it go. When he moves out, we can demolish

the entire second floor and then

renovate it like on one of those shows you like.”

“Haha,” said Cheryl. “But

this is not a joke.” Then

over her shoulder, as she walked away, she

added, “And you’re late.”

“I got caught up on the Duncan account,” Martin explained

as he followed her, waving at his parents along the way.

Grandpa Reinhold nodded as he stared at the screen

while his wife continued flipping through the pages

of her magazine before taking another sip of wine.

In the kitchen, Cheryl started to work on dinner. “I

don’t know why you can’t take the week off.”

“You didn’t,” said Martin as he began removing his suit

jacket.

“I’m taking Wednesday.”

“That’s not the whole week.”

As she pulled a pot out of a cabinet, Cheryl shook her

head. “Let’s not do this right now, okay?”

Martin leaned on the counter. “Okay, but I think it’s a good sign that I have to work late. I’m

getting more responsibility. I told you about that account, didn’t I?”

Rifling through a cabinet, Cheryl said, “You did.”

“So, I’m thinking they

might make me partner.”

“Which is what you said last year, and look at what happened.”

Loosening his tie, Martin sighed and said, “I know, but

this is different. I can feel it.”

Cheryl stopped filling the pot. “You don’t feel a promotion. You

ask for one, Martin. Or a raise, for that matter. You could use one of those

too.”

Martin nodded. “I’ll get my bonus this year. And

it should be pretty hefty.”

“We’ll see.”

“Hey, what’s the matter?”

“Nothing.”

“Nothing?”

She glanced toward the living room, lowered her voice, and said,

“I’ve been home half an hour, and your mother is already driving me out of my

mind.”

“What’d she do?”

Cheryl mouthed her next statement. “Keep your voice down.”

Whispering, Martin said, “Okay. What’d she do?”

“She suggested we make Thanksgiving dinner, but I’ve already reserved a meal from Whole Foods.”

Martin looked over his shoulder. “Mom wants to cook?”

Continuing to fill her pot

with water, Cheryl said, “She wants all of us to pitch in, but,

honestly, do you really want your Mom cooking

anything?”

Martin shrugged. “Maybe if we’re having something with

wine as an ingredient.”

Cheryl gave her husband a look.

Martin moved toward the doorway to the living room. From there, he could see that his

mother was reading a cooking magazine.

“Oh no.”

“What?” asked Cheryl with her voice still lowered.

“She’s going through a phase.”

“A phase?”

“Yes,” said Martin, stepping closer. “You know, she gets hooked on things. She must be on cooking right

now.”

“She said she has a pumpkin pie recipe.”

Martin shook his head. “No. Under no circumstances can

she make the pumpkin pie. That’s my favorite part of Thanksgiving dinner.”

“Then you talk

to her.”

Martin closed his eyes briefly before starting

toward the next

room. Standing over his mother, he said, “So, Mom, I see you’re reading a cooking

magazine. Have you been getting into cooking lately?”

“Has she ever,” said Grandpa Reinhold as he straightened

in his chair and looked away from the television. “She made a chicken last week

that was the juiciest thing I’ve ever tasted.”

“Really?” said Martin.

“Oh, it was beginner’s luck,” said Grandma Reinhold

as she gazed up at her son.

Martin noticed that his wife was leaning against the door

jam behind him. Then, turning back

toward his mother, he also saw that his father was shaking his head and giving the thumbs

down while his wife wasn’t looking.

“Well,” he said, “that sounds great, but why don’t we leave the Thanksgiving dinner to professionals this year.”

“Oh, come on, Martin,” said Grandma Reinhold. “How hard

can it be?”

“Yeah,” said Grandpa Reinhold. “I’d just love a homemade

Thanksgiving dinner. And if the turkey turns out dry, so what? Turkeys are always dry as hell,

anyway.”

“Well, it’s a lot of

work,” said Martin. “And we reserved a pre-made meal from Whole Foods.”

“Hosh-posh,” said

Grandpa Reinhold. “Let’s make it a family thing. I’ll whip up some of my famous

mashed potatoes.”

“You’ll make your mashed potatoes?” asked Martin. “With

the parsnips?”

“Of course,” said Grandpa Reinhold.

Martin looked back at Cheryl. Shrugging, he said, “Well, it sounds like it

could be fun.”

Cheryl returned to the kitchen, sighing out of exasperation as she went. Martin followed her.

“Honey,” he said, “it’s what they want to do. I mean,

let’s face it. They don’t have that many Thanksgivings left.”

Cheryl stirred the rice on the stove. “Martin, your

father just doesn’t want to be the bad guy. And, apparently, neither do you, which means I’ll be doing all of the cooking.”

“I’ll help,” offered Martin.

“Your cooking’s worse

than your mother’s.”

Martin leaned against the kitchen counter. “Well, what do

you want me to do? They were probably expecting a homemade meal because that’s

what Helen did last year—at her place.”

“I don’t care what your sister did. We have a meal reserved.”

“How about this?” he said. “I’ll cook. I’ll run the show,

and you won’t have to worry about a thing.”

Cheryl turned toward him. “You can’t cook.”

Martin stepped toward his wife and took hold of both shoulders again before saying,

“That’s what the Internet’s for. I’ll learn how

to cook a turkey. As for everything else, I think I can handle a can of

cranberries, some green beans, and toasting a few rolls, don’t you?”

Cheryl sighed, then said, “Just don’t burn the house down… like you almost did last night.”

As Martin stepped away, he said, “Don’t worry, that was a one-time thing.”

Nov. 23

“So, let me get this straight,” said Jim, chuckling to

himself. “You’re cooking Thanksgiving

dinner?”

“Yeah,” said Martin as he sipped his coffee.

Maggie stood in the break room, pouring hers. “You’re in for a real treat, my friend.”

“Come on,” said Martin. “How hard can it be?”

“How many people?” asked Jim.

“Nine.”

“Nine!” exclaimed Jim before shaking his head.

“It’s not that big of a deal. I’m sure my sister will

help. She cooked last year.” Facing two unconvinced coworkers, he continued,

“Okay. I might be in a little over my head. But what do you know about cooking,

anyway, Jim?”

“I happen to know my way around the kitchen, Martin.”

“Ooh, big talk,” said Maggie as she sipped her coffee.

Jim shot her a look. “I’ll have you know I have a set of

chef-quality knives at home.”

“I’m surprised you haven’t cut a finger off,” continued

Maggie, taunting him.

“I almost did when I first got ‘em.” Jim pointed at the

scar on his forefinger before adding, “All the best chefs have scars.”

Maggie rolled her eyes, then looked at Martin and said,

“We’re just giving you a hard time. I’m sure it’ll

be fine.”

“Speak for yourself,” said Jim. “I think it’s going to be

a shitshow.”

“The important thing is that the family is together,” said Martin.

Jim and Maggie both laughed before Maggie left the room.

Jim followed, saying, “Gobble, gobble!”

#

Life was carrying on as usual in the Reinhold house that

evening. Martin’s daughter was out with her boyfriend, who had now been invited

to Thanksgiving dinner, which made 10. (But Martin

didn’t think this would cause too much of a

problem. Cooking for ten couldn’t be much different than nine.) Will was

upstairs playing video games, and Cheryl was starting dinner. The only thing

remotely out of the ordinary was his parents.

They’d become fixtures in the living room—his mother boozing it up and his

father watching SportsCenter.

It certainly seemed like

the holidays.

After taking a seat on the couch, Martin turned to his

mother and said, “So, how was your day, Mom?”

“Same as any other day.”

“We went for a walk around the neighborhood,” added Grandpa Reinhold. Then, without

taking his eye off the television, he said, “How was work?”

Martin said, “Same as any other day, I guess.”

Grandma Reinhold humphed.

Then Martin asked, “What time are Helen and Bill getting here tomorrow?”

“They’re flight comes in at 3,” answered Grandpa Reinhold, “but they probably won’t be here ’til about 4.”

“And you’ll still be at work?” Grandma Reinhold asked.

Nodding, Martin said, “I’ll be at work, but I’ll get home

as fast as I can.”

Grandpa Reinhold shook his head as he watched a replay on

SportsCenter. “Can you believe that

catch?”

Ignoring his father, Martin turned to his mother and continued,

saying, “I have Thursday and Friday off.”

“I’m surprised you’re not working Friday,” said Grandpa

Reinhold, whose eyes remained glued to the

screen. “I would if I could. This place is gonna be a looney bin.”

Martin was smiling as he entered the kitchen. “Can I help

with anything, dear?”

Cheryl looked up at him.

“It’s almost finished.”

Martin nodded. “We should order out tomorrow night when

Helen and Bill get in. What do you think?”

“Sure.”

Martin tried to embrace his wife, but she sidestepped him

and went to the fridge, where she took out a can of Parmesan cheese.

“Spaghetti again, huh?” said Martin as he shoved his

hands in his pockets.

Cheryl, who was still wearing the navy dress pants and

cream-colored blouse she’d worn to show a house earlier that afternoon, closed

the refrigerator door, saying, “It’s Will’s favorite.”

#

Later that evening, Martin cuddled up next to his wife.

After nuzzling her ear, he kissed her on the cheek.

“What are you doing?”

“What do you think

I’m doing?”

Cheryl groaned. “I’m tired, Martin. And your parents are

here.”

“They’re downstairs. And it’s not like we’re gonna get that loud.”

“No,” she said flatly, “we’re not.”

“Hey, what’s the

matter?” asked Martin as he sat up on his elbow.

“Do we have to talk about this right now?” asked Cheryl as she rolled over to face him.

“Why not? We hardly ever talk.”

Cheryl sighed in the dark. “I’m just not in the mood.”

“I could put on some music.”

“That’s not—I have a headache,” said Cheryl before rolling back over.

Martin bit his lip, then decided to climb out of bed and maunder downstairs. After rummaging around in the freezer, he

found a box of ice cream sandwiches. Sitting

in a dark living room, wearing his boxers and

an undershirt, Martin took a bite of his ice cream.

A few moments later, he heard someone coming down the steps. Peering through the darkness, he said, “Will?”

The boy screamed as Martin reached for a lamp and turned it on.

Will looked at his father and said, “You scared me.”

Grandpa Reinhold entered the living room a moment later, tying his robe. His wife was behind him with an eyeshade on top of her head. Martin’s father said, “What the hell’s going on out here?”

“I scared Will,” Martin

explained.

“What are you doing down here, Dad?”

Martin took another bite before saying, “Eating ice

cream.”

As Grandma Reinhold turned around and started back toward

the bedroom, Grandpa Reinhold said, “Ooh. I could go for a midnight snack.”

“Me too,” said Will.

By the time Grandpa Reinhold returned to the living room,

Sarah was coming down the steps in an oversized t-shirt and shorts. “What are you guys doing down here?”

“We’re having ice cream,” said Grandpa Reinhold cheerfully.

From the foot of the

steps, she said, “Is there any left?”

“I got ya’,” said Grandpa Reinhold as he spun back

around, heading toward the kitchen.

When his father returned, Martin said, “Let’s just try to

keep it down. Your mother has a headache.”

Nov. 24

There weren’t many people in the office on Wednesday, so

Martin could work without distractions. He was

so efficient that by the time 3:30 p.m. rolled around, he’d started to think he could make it home in time to welcome his sister

and her family. After shutting his computer down and packing his things, Martin

began making his way out of the sparsely

populated office building. He was near the front desk when he ran into Mr.

Gruber—a firm namesake and a shifty miser with

a penchant for country clubs and luxury

sedans.

“Mr. Gruber,” said Martin, who attempted to hide the fact

that he was leaving by not so subtly shifting his briefcase behind his back.

“Finegold. How are you?” said Mr. Gruber in his raspy, croaking voice.

As the older man appraised Martin, he said, “It’s actually Reinhold, sir.”

Mr. Gruber narrowed his beady little eyes, saying, “Yes,

of course. Isn’t that what I said?”

“I think you said, ‘Finegold,’ sir.”

“Oh yes,” said Mr. Gruber, who began picking at a

piece of lint on his pinstriped suit. “I must’ve

gotten you confused with our associate Martin Finegold.”

“You must have,” said Martin, grimacing as he looked

toward the parking lot. He was just so close to freedom.

“So, are you planning a

big Thanksgiving this year? What did you say your name was again?”

“Martin.”

Mr. Gruber made a face, “Well then, Martin, are you planning a big Thanksgiving?”

“Oh, yes, sir.”

“Humph,” said Mr. Gruber, nodding. “Then let me ask you something else: Do you like turkey?”

“Not particularly, sir.”

The older man nodded

again. “I don’t know many who do, but we eat it every year, don’t we? What does

that say about us?”

Martin shrugged. “That we enjoy traditions?”

“No, it says we’re as foolish as the stupid, timid birds we devour.

Tell me, can a tom turkey learn or plan for the

future? Can he?”

“If he could, he might plan an escape sometime before Thanksgiving,” said Martin.

Mr. Gruber looked at Martin and laughed. “Very good. Yes,

he would make a break for it,

wouldn’t he?”

Martin nodded.

“But he can’t!” exclaimed Mr. Gruber suddenly, which

caused Martin to stiffen. “He can only be led to slaughter.”

Martin swallowed.

“And so it will be,”

said Mr. Gruber, menacingly.

“Are you having turkey for Thanksgiving this year, Mr.

Gruber?”

“Yes, I am. I believe my

wife is having our meal catered from Whole Foods.”

“Is that right?”

“Well, you have a nice Thanksgiving, Finegold.”

“Thank you, sir,” said Martin before he exited the

building through the double doors.

#

Martin pulled into the driveway just after 4 p.m., but his sister and her family had yet

to arrive. Grandpa Reinhold informed him that their flight had been delayed.

So, Helen, a plump woman with red hair, her rail-thin husband Bill, and their

young daughter didn’t arrive until a little after 8 p.m. that evening.

After taking just a few steps into the house, Martin’s sister dropped her suitcase and cried out, “Oh my God! We finally made it!” Looking to Martin, she added, “Why does everyone travel the day before Thanksgiving?”

Bill was a balding man with gold-rimmed glasses in a navy mock turtleneck. He said, “Do you have anything to drink, Martin? Preferably something stiff.”

“Sure, Bill. I’ll make us both a drink.”

Martin escorted his family into the living room and then

went to get his sister a glass of wine. He planned to join Bill with a

tumbler of bourbon for himself. Grandpa Reinhold was

cuddled up on the couch next to his

granddaughter, Jessica. With the young girl beaming as she looked up to him, he said, “So, how was the flight for you, dear?”

“Long,” answered the red-headed six-year-old.

“So I hear.”

Helen leaned over and hugged her father next. “Hey, Dad.

Where’s Mom?”

“She’s freshening up.”

Grandpa Reinhold stood and shook Bill’s hand as Cheryl emerged from the kitchen. She hugged

Helen, saying, “You three must be starving. We

took the liberty of ordering some Indian food. We’ve eaten, but there’s plenty

left.”

“That sounds perfect,” said Helen, “except that Indian food upsets Bill’s stomach.”

“Guilty,” cried Bill as

he held up a hand.

“Oh no,” said Cheryl.

“I’d make a terrible Indian,” joked Bill as he entered the

kitchen, sipping his bourbon.

“What do you mean?” asked Cheryl as she went into

the pantry.

“Because I can’t eat Indian food.”

“Oh,” said Cheryl. “Well, I’m sure we can find something

else in here.”

Martin knocked his

bourbon before saying, “I guess it’s a good

thing the Indians at Thanksgiving weren’t India Indians.”

“Columbus thought they were,” said Bill haughtily. “But speaking

of sensitivities, I’ve also developed a slight

allergy to wheat.”

“It might be gluten,” added Helen as she busied herself with the food.

As he began

pouring himself a second drink, Martin said, “We’re going to be having

cornbread for Thanksgiving dinner. Will you

be able to eat that?”

“I should,” said Bill.

“But if we could have the stuffing on the side, that would be great.”

“Sure,” said Martin, who began calculating how much more

complicated a food allergy would make his meal

prep. “No problem.”

Nov. 25

Thanksgiving morning, Martin was up before six

o’clock, making a game plan for the day. The first

thing on his list was cubing bread for the stuffing. After that, he started chopping

vegetables for salads and sides. He was moving right along to the cranberry

sauce when Cheryl entered the kitchen, took a look around, and said, “Wow. It

looks like you’re really on top of things in here.” Then she narrowed her eyes

and said, “Is that my apron?”

Martin glanced down at the flower-patterned apron around his

waist. “Is that okay?”

“You know, it doesn’t look that bad on you. A little small, but other than that…”

Martin ignored the comment and continued working,

saying, “The turkey’s thawed, right?”

“I think it’s had enough time,” answered Cheryl. “We

bought it on Monday.”

“That’s three days,” said Martin. “It should be fine.”

Cheryl leaned on the counter next. “Do you want any help?”

“Honestly,” said Martin, looking up from the

cutting board. “Mom’s going to be in here soon making

pie. And Dad’s going to be making his mashed potatoes. So, I think we’ll already

have one or two too many cooks in the

kitchen—especially for one this size.” Martin glanced over his shoulder at a

space that was no more than 10’x10’ in size.

“Okay,” said Cheryl. “Well, you know where to find me.”

“Thanks, but I won’t need help,” said Martin confidently.

“It’s cooking, not rocket science.”

Before Cheryl

left the room, she said, “Considering the fact that

you’re neither a chef nor a rocket scientist, I’m not exactly sure how

to take that.”

Martin smirked as his mother appeared, wearing a purple muumuu. She went straight for the refrigerator, saying, “Everyone stand back!

Grandmama’s making pies.” The older woman stopped with the door open, adding, almost to herself, “But first things first, I need a little wine with my cooking.”

“It’s eight o’clock in

the morning,” said Martin as he began opening a second can of cranberry sauce.

“I’m sure that doesn’t stop Martha Stewart,” said Grandma

Reinhold. “Especially on a holiday.”

Martin shook his head as his mother poured herself a

glass of Chardonnay and stole his can opener so she could get to work on the cans of pumpkin filling.

Next on Martin’s list was the stuffing.

He worked alongside his mother in the kitchen, reading the recipe off of a tablet. There were several tabs open at once with various recipes as he’d also set to work on his green bean and sweet potato casseroles. Martin placed the sweet potatoes in the microwave, then put the turkey in the oven. After that, he looked around briefly and wiped his hands on his wife’s apron, thinking to himself that things were going remarkably well.

Grandpa Reinhold entered the room a little while

later, saying, “Is there room for a little potato peeling?”

Martin pointed to the sink. “That area is all yours. And I’ve already started peeling.”

“Oh wow. Thanks, son.”

Meanwhile, Martin was at work on a butternut squash soup.

The corn shucking was to come after that.

While he was working,

Helen snuck into the kitchen, saying, “How’s it going?”

“Good,” said Martin, nodding.

“Well, do you think there’s any room for me in here? I

wanted to surprise Bill with some gluten-free

stuffing.”

“Oh,” said Martin. “I don’t think we—“

“Great,” said Helen, interrupting him. “I brought everything I need.”

Just after Helen entered

the kitchen holding a few grocery bags, Sarah

rushed in, jumping up and down and saying, “Dad! Dad, I need

to talk to you like, right now.”

Cheryl stepped into the room behind her daughter,

leaning against the door jam with her arms crossed.

Martin looked up from the corn he was shucking and said, “I’m a little busy right now, Sarah.” As he moved to trash a

husk, he bumped into his father.

“Watch it!” said Grandpa

Reinhold. “I’m wielding a large knife here.”

He held up the eight-inch blade.

“Sorry about that.”

“Dad,” whined Sarah.

The

young woman tucked her hair behind her ears and stepped closer.

Martin leaned on the

counter. “Okay, what is it?”

“Jake invited me to spend Christmas in Vail with his

family. Can I go? Please!”

Martin took a moment to absorb the content of the

question, then shook his head. “No, absolutely not.”

“Why not?”

“For one,” he said as he glanced at Cheryl, “we don’t know Jake’s parents.”

“Dad, I’m 18 years old.

This isn’t a spend the night party.”

“She has a point there,” said Helen.

Martin snapped at his sister. “You stay out of this.” Then he returned to Sarah, saying, “I wasn’t finished. Secondly, I want you here with us. It’s

Christmas.”

“Then can I go for New

Year’s?”

“How long are they staying there?”

“Two weeks.”

“No,” said Martin, “you

should be here for New Year’s too. Right, Cheryl?”

Cheryl said, “I said I thought it was okay if she wanted to join them after Christmas.”

Martin narrowed his eyes and began shaking his head as he

looked down at a carrot he was cutting. “Well, I don’t think—”

Grandpa Reinhold was

sniffing the air again. “Do I smell smoke?”

Martin spun on his heels.

“The pies!” cried Grandpa Reinhold as he opened an

oven door, and a plume of thick gray smoke billowed

out.

Grandma Reinhold was the last one to appear in the

kitchen. When everyone looked at her, she took a sip of wine and said, “I guess

they’re done.”

#

Dinner was served at three o’clock in the afternoon. A

cornucopia of turkey, bread stuffing, mashed

potatoes, rich, creamy gravy, green bean casserole, corn, toasted dinner rolls,

and cranberry sauce adorned a table covered in a linen tablecloth. Martin had

planned to have dinner at two, but he counted it a success that everything had

come together at approximately the same time. When he and Helen finished

bringing the last of the food to the table, he took off his apron and yelled,

“All right, everybody! Let’s eat!”

Once the Reinholds, Helen’s family, and Jake were seated,

Martin said, “Why don’t we start dinner by going around the table and saying

what we’re thankful for? But let’s keep it short and sweet. I wouldn’t want any

of this delicious food to get cold. Okay?”

Everyone nodded or murmured in agreement as they gazed upon the glorious feast

before them.

“I’ll start,” said Martin. “I’m thankful for this wonderful meal that I have prepared for us on this wonderful Thanksgiving Day. Who knows? Maybe we’ve started a new tradition of me doing the cooking.”

He raised his wine glass.

“I helped, you know?” said Grandpa Reinhold.

“Well,” said Martin as he winked at his son, who

was sitting beside him. “You made some potatoes. It

takes serious skill to roast a turkey.”

Will was next. “I’m thankful for pumpkin pie!”

When Grandma Reinhold

heard this, she downed almost an entire glass of Chardonnay.

Martin’s daughter went next. She looked at her boyfriend and said, “I’ll be thankful when my father

changes his mind and lets me go skiing this Christmas.”

Jake—a young man with dirty blonde hair parted on the

side—followed this statement by saying, simply, “Um, thanks for inviting

me. Everything looks great.”

The Reinholds continued

to go around the table this way until they came to Helen, who was the last to

give her sentiment. She said, “I’m just thankful to be here with all of you, my

wonderful family. You’ve been such a blessing in my life, and I can’t express

how much I love you all. And on this Thanksgiving, I just hope that we all

realize how much we have and how fortunate we are to have it. I mean, that’s

what Thanksgiving is really about, isn’t it?”

Everyone nodded as Martin stood to carve the turkey.

Looking down at his sister, he muttered, “Did

you rehearse that or something?”

“I was speaking from the heart, Martin.”

“Either that or those depression pills are finally

kicking in,” said Grandma Reinhold before rolling her eyes.

“Mother!” said Helen.

“What? You don’t want

everyone to know you’re taking happy pills?”

“Mother, please!”

Bill spoke up next. “That’s private medical information, Mom.”

Grandma Reinhold smirked. “I just thought everyone should

know she has a reason for being so thankful.”

Still standing by the turkey, Martin said, “Well, we

should all be so thankful.

Anti-depressants or not.”

Helen bristled, saying, “I have a seasonal mood disorder.”

Grandpa Reinhold leaned forward. “A gray day can get anyone down.”

“It’s a little more serious than that, Dad,” barked Helen.

“Well, you can’t have it both ways, dear,” said Grandpa Reinhold before he started passing the

green bean casserole.

Will uncovered the rolls and cried out, “Hey, these are burned!”

Martin put some dark meat on a plate, saying, “Scrape it off. A little

char isn’t going to hurt you.”

Will made a face but still took one of the rolls.

Meanwhile, Cheryl took a bite of the green bean casserole

and said, “Is this… cinnamon?”

“Cinnamon?” asked Grandma Reinhold. “In the green bean

casserole?”

Stopping mid-cut on the turkey breast, Martin said, “What’s the problem?”

Cheryl scanned the

table. “Where’s the sweet potato casserole?”

“It’s… Well, I think it’s—“

Grandpa Reinhold passed the cranberry sauce, saying, “I saw some sweet potatoes in the microwave when

I was reheating the mashed potatoes.”

Bill offered his

daughter a gluten-free dinner roll, saying, “Mom

made plenty of mine if

you’d prefer to have one of these.”

Cheryl spoke across the table, saying, “You put the

ingredients for the sweet potato casserole in the green bean casserole?”

Moving a bean to the side, she said, “Is this a marshmallow?”

Martin said, “I could

have sworn—“

Bill took a bite of

stuffing as Helen said, “Bill! That’s not the gluten-free

stuffing!”

“Oh. Oh no,” said Bill

before spitting a mouthful into his napkin.

Meanwhile, Grandpa Reinhold was sipping a can of beer

and clearing his throat, saying, “The turkey’s a

little dry, isn’t it?”

Looking toward Martin,

Cheryl said, “Did you baste the turkey?”

“Yes!” said Martin. “Of

course I basted it.”

“Not enough,” said Helen as she forced down another bite.

“Really dry,” said Grandpa Reinhold as he coughed. “And this is the dark meat?”

“I told him he needed to baste it,” Helen continued,

leaning forward to make her comment clear to

Cheryl, who was sitting at the other end of the table.

“Henry!” cried Grandma Reinhold as she slapped her

husband on the back.

“Oh my God,” screamed Sarah. “Grandpa’s choking!”

She stood to move around the table, but Martin was already on the way. After pulling his father out of his seat, he began performing the Heimlich. One thrust into the stomach, then another, and another until Grandpa Reinhold finally rocketed a wad of half-chewed turkey across the room.

Sitting his father back down, Martin said, “Dad, are you

okay?”

“I’m fine. I’m fine, but I definitely thought I was a

goner there for a second.” He made the statement reaching for his ribs.

“Are you all right, Grandpa?” asked Jessica.

“Yeah, I think so, dear.”

As everyone returned to their seats, Martin turned and

looked at his family. His daughter was texting;

her plate pushed away. Her boyfriend was

eating his meal but grimacing with each bite. Despite nearing a drunken stupor, Grandma Reinhold was

pouring herself another glass of wine, opting for a liquid Thanksgiving. Helen

had barely touched her plate, and like her father, it was starting to look like

she had no intention of eating anything else.

It was no different for Martin’s wife.

The accountant-turned-failed-chef had no choice but to suspect it was because they all felt

like his son, who was making his cousin laugh by gagging and pointing at his green bean casserole.

The only one who appeared to be enjoying his

food at all was Bill.

But most of what he was eating had been

prepared by his wife. After biting into a

turkey leg, Bill turned to Martin and said, “I

don’t think the turkey’s that bad, Martin. Especially if you wash it down with

a little water.”

Thinking of all the hours he’d spent on this meal,

how ungrateful his family was being, and the fact that he hadn’t slept with his

wife in more than six months, the middle-aged man exploded.

He stood once more, saying, “You know what!”

Martin picked up the 15 lb. bird at the head of the table before continuing, “I spent all day preparing Thanksgiving dinner for you people, and not one of you is eating it. Not a single one of you has even thought to thank me!” Moving toward the front door, he added, “So, why don’t I just make sure you don’t have to suffer through another bite.” When Martin reached the front door and realized he couldn’t open it with a platter in his hands, so he said, “Will, could you come open the door?”

Cheryl turned toward her husband. “Martin.”

Will was hesistant until

his father repeated himself.

“Don’t do it!” cried

Cheryl.

As Cheryl stormed out of the dining room, Martin

launched the dry turkey out into the yard from the front stoop. When he turned back

around, he was seething.

“Be thankful for that!”

“I know I am,” said Grandpa Reinhold. “Another bite of

that bird might have killed me.”

#

A few hours later, most of the adults were sitting in the

living room while the young children watched

TV in the basement. Everyone was full of Chinese takeout and discussing the predictions inside their fortune cookies. While Martin’s travails in the kitchen had gone widely

unappreciated, he realized he might have overreacted

and was counting himself lucky no one else had

choked on the overcooked turkey.

Meanwhile, his wife was sitting on the opposite side of the living room, shunning him. Bill had developed a slight rash and a little bit of cramping from the ingestion of the gluten-filled stuffing, but, fortunately, it had not been enough to spark an emergency. Sarah had gone to visit with her boyfriend’s family, and Grandpa Reinhold was suffering no ill effects from his incident other than a few sore ribs. It was starting to seem like the day was not a complete loss until Will and Jessica came upstairs, asking if they could go outside.

The children were in the front yard for no more than a few

minutes before they hurried back in. Will rushed through the door, saying, “Dad! Dad!”

Martin put his wine glass down. “What? What is it?”

“There’s a dead squirrel beside the turkey.”

“It looks like it was eating it!” Jessica exclaimed.

Martin glanced at his father, who put his beer down and shook his head before saying, “Somebody call a doctor. It looks like Bill’s cramping isn’t from gluten, after all.”

BIO

Justin Meckes lives and writes in Durham, NC. He has published stories

in journals and magazines such as Map Literary, The Broadkill Review,

and Idle Ink. You can learn more at justinmeckes.com.