Dream On

by CL Glanzing

Sinead Simon has a toothache. She prods it with her tongue hoping to find a dullness through the sting. In the night, curled in her sleeping bag, with the wind whipping the tent against her knees and head, she imagines using her adjustable spanner to rip the belligerent bastard from her aching gum. But it is unlikely she could remain silent throughout. She will not even make a fire to draw attention to her presence. She has become accustomed to softening her steps, keeping the gas stove on low. She knows where the ivy is pulpy and easiest to step through, and where the blackberry brambles make trip-wires across the forest floor.

Ten metres behind her lies the wall, above the moss-drenched ditch with its lattice of dead logs. Narrow, wrought-iron slats — four inches thick and six feet high. A row of dense boxwood lines the inside of the fence, prickling branches through the slats and obscuring the house on three sides. The only breach is a narrow, but regal, iron-framed gate with wood infill. But it never opens, and the red eye of the camera on its shoulder never dims.

Sinead paws her feet in her sleeping bag, flexing and curling. She is snug, being so constricted. She knows where she is. The immediate world is known.

At 06:50 she emerges from her nylon cocoon. She wiggles the hot water-bottle from the feet of her sleeping bag and tips the cold contents into the bushes. She sometimes likes to end the evening with it zipped into her jacket, stroking it like a pregnant belly.

She laces her boots and pockets her waterproof notebook and pen. She hangs her field binoculars around her neck. Her hands circle the trunk of the beech tree under which she camps. She finds purchase on a low branch and a deformed knot at shoulder height, lifting her weight. She steps into the Y of the beech and swings carefully as she climbs higher and higher. She straddles a thick branch running parallel to the ground and jutting forwards in the direction of the house. She slides herself forward like an inchworm, buttocks raising and pushing her torso forward until the glass box house is in clear sight. She lifts her binoculars and points them towards her subjects.

The Lady in White sits at the kitchen island, sipping from a porcelain espresso cup. From the beech, Sinead has a clear view of the entire lower floor – the black leather sofa, the oak dining room table, the chrome kitchen. The french doors leading to the manicured lawn and, a little ways down, the tasteful gazebo and koi pond. Above this floor is the master bedroom, just behind a balcony with frameless glass.

Sinead watches the Lady waft to the sink and carefully rinse and dry her cup. She wipes her finger along the underside of the espresso machine and then rubs her fingers together. She then wets a cloth and rubs where she has found the dust or grime or whatever has displeased her.

The Lady returns to the kitchen island and kneads her temples in a circular motion for a while, slowly, until she is sitting with her fingers framing her face, as if attempting some trick of telepathy. She stares out the window of the glass house in the direction of the lawn.

Sinead wonders where the Lady’s mind has gone. She is coldly vacant, expressionless. Perhaps melancholy.

The Lady is warm and dry, cuddled in a cashmere cardigan and soft slippers. There is fruit on the kitchen island, central heating, a teepee of logs in the fireplace. And yet, she does not want to be here.

Sinead thinks about the two blue macaws in her aunt’s house. ‘I think they want out,’ Sinead had said, looking at the majestic birds perched in their cage. Looking into their black eyes, still like shadowed caves, she convinced herself she could see a light within, pleading and restless. ‘Don’t anthropomorphize,’ said her aunt.

Sinead does not want to be biassed. She reminds herself not to interpret, just record the physical phenomenon in her little notebook: lips turned downwards, unfocused eyes, sighing.

And then she reminds herself: Confirmation bias – the experimenter interprets results incorrectly because they are looking for information that confirms their hypothesis and overlooks information that argues against it.

She is probably the worst scientist for this job, but also the only one that can perform it.

Another figure comes into the room with the Lady. She watches her speak some words as the figure packs a suitcase on the dining room table. The Lady is kissed on the cheek and she smiles warmly. Then she is left alone.

Sinead cannot see the Mercedes departing the garage, but she can hear the gravel crunching under its weight, and the electric gate drawing back and then piercing shut in the car’s wake.

The Lady goes upstairs and changes out of her cream robe and into grey leggings and a grey sports bra. Sinead knows the rest of her morning routine. Elliptical for an hour, followed by a green smoothie. Then she will sit on the sofa and play CandyCrush – she once left her tablet propped on the sofa facing the window. There is only one computer in the house, but it’s in the study and the Lady never uses it. She has her tablet.

She lets the Waitrose delivery in through the gates on Friday afternoons. And the maid comes Mondays at 10:00. Sometimes she’ll read a book – Sinead’s binoculars are not sharp enough to read the titles.

Sinead knows the Lady has a PhD in mediaeval literature. And used to teach at the University of Essex until three years ago. Now she is on sabbatical, returning tee-bee-dee. Conducting neither research or maternity leave. Snow White pacing in her glass coffin.

Sinead should call the Lady by her real name – Dr. Elizabeth nee Marjoribanks. But the Lady in White feels better. Makes it more objective in her reconnaissance, and gives a mythic power to her observation. Like debunking a ghost spotted by a local farmer. A ghoulish folk-story moulded and churned in the minds of the frightened villagers – an obscene blemish on their perfect town. And Sinead wants nothing more than to prove it wrong, methodically, scientifically. Pull the mask off the ghost and declare, ‘Ah-HA! It was the janitor all along! And here are the missing church alms.’

Δ

Sinead is not new to science.

At a bioengineering conference, she stood in row EE of the conference hall in front of a vinyl poster describing the impact of deep brain stimulation on phantom limb pain. As second author, she began to feel wholly anonymous in the rows upon rows of colourful posters. Only the young researchers seem to be standing next to their work, searching for eye contact from passersby, like hopeful puppies in a department store window.

Just the week before, her gladiatorial pursuit of a PhD grant bestowed by the Scottish Research Council had gone to another student with whom she shared a closet office. Her career prospects were seeming their bleakest.

Then a handsome man with walnut hair and panto glasses approached.

He frowned as he read the text behind her head, not looking at Sinead directly. Indicating with his cup of Starbucks and still avoiding her eye, he spoke: A little derivative of Jenkins et al, don’t you think?

‘Well, unlike Jenkins, we used aggregated data,’ she replied.

He pursed his lips and raised his eyebrows as if to say, Perhaps, perhaps.

He eyed the other bodies mingling around the rows of posters, and said offhandedly, So, tell me something I don’t know yet. It sounded rehearsed, clearly directed to every new person he encountered. She did not really want to engage in such an obvious goading, but she felt compelled. She did not know who this man was, but she did not want any conference gossip painting her as a poor sport, or unenthusiastic.

‘Well, I think this technology will be in everyone’s homes in 20 years.’

He exhaled sharply through his nose, half-laughing at a private joke. Sooner than that, he said.

He handed her a card – ‘Jack Delaney, Founder’ – and told her to stop by his start-up’s stall. By the end of the evening, he had offered her a job and she waved goodbye to her PhD pipedream.

He was fascinating, pensive, with a penetrating stare like a harrier. He did not suffer fools gladly. The slightest unintelligent or unoriginal opinion, he nipped at its heels, sometimes fearcely enough to draw blood. He was sarcastic, with a dark humour bordering on cruel. But his observations on chemistry, biomedicine, and neurosurgery were astonishing. He was a database, casually referencing literature like he was pulling light from the aether. Not just citing, but deconstructing, destroying, and reassembling the pieces into an empire of his choosing. He cackled like a young boy when something delighted him, and he stabbed his finger in the air to punctuate displeasure.

At dinner, after the conference, his colleagues started talking about their new project – the use of delta sub-4 frequencies to de-synchronise abnormal oscillations in brain neurons.

‘Interesting,’ said Sinead. ‘What for?’

The table laughed. They looked to their leader seated at the top of the table, waiting for the word of God. He took a sip of his beer and said, We’re going to cure mental illness.

Δ

Sinead shimmies down the tree. She takes her gas stove from out of her tent, and twists the dial to snap the blue flame into life. Nothing happens. She clicks it a few more times before concluding that the gas canister is empty. She had to order them online especially before she left.

No more hot meals. Her hot water bottle will remain empty at night. Which is not really a problem, considering it is May.

And she has learnt to ignore ‘wants’. The meringue-softness of a duvet, porcelain sinks, plastered walls. She has concluded that wanting comes from the stomach; needing from the head. And wanting is weakness. It says you are not self-sufficient, that there is a hole inside you that you cannot fix with a hot meal. It means that you may not survive. You are looking down from the tightrope – suddenly aware of your precarious existence. Un-wanting is self-preservation and acceptance.

But the inability to boil water from the stream – that will be a problem. She will have to walk the seven miles to the petrol station with the small corner shop.

In this sleepy Surrey village, the roads cut through steep embankments with few shoulders or gutters. They are punctuated by wide driveways that declare the property names in large, rustic fonts – Badger Cottage, Oak Stables, Mosswood Farms, Bramble Lodge. The ‘cottages’ always seem to be the size of aeroplane hangers. These kinds of properties are never sold – only if the occupants are childless and needing to go into specialised care homes. Otherwise, they are inherited and exchanged between the hands of the same small group of upper middle class snobs. There was always the nouveau riche outlier – actors, hedge-fund managers. Tech billionaires.

Parts of these open fields make Sinead angry – all that space just sitting there when twice the population is stacked in high-rises half the square footage in the city. Despite the majestic breathlessness that stirs in her when she sees a horse cantering through a field, she can empathise with the current political movement to have them banned in Britain. Too much space for a creature that does nothing but offer vein entertainment for rich cunts to stroke and brush and race. Not that such a bill would ever pass through those very same rich cunts sitting in the House of Lords.

When Sinead arrives at the petrol station, she is feeling parched and her knees ache. She first checks her balance at the cash machine outside by pressing her thumb to the fingerprint reader. £56. Fuck.

After she has purchased enough canned vegetables and bags of peanuts to fit inside her backpack and two gallon water jugs, Sinead reluctantly walks into the public telephone booth next to the cashpoint, and presses her thumb against the screen to access her cloud contacts. She simultaneously hopes and dreads the end of the dial tone.

‘Hello?’

‘Hi Natalie. It’s Sinead.’

‘Oh my god, where are you?’

‘Listen, I’m going to be a while longer and -’

‘-I haven’t heard from you in three weeks. I’ve been going out of my mind.’

‘I know, I’m sorry. My solar battery died.’

‘When are you coming home? You can’t possibly still be camping. My mobile says you’re calling from Dorking… Why – why are you in Dorking?’

Sinead’s mouth is a hot, dry cave sloshing saliva around and around. Get to the point, she tells herself.

‘Natalie, I need you to give my two weeks’ notice. Please can you cancel the standing order with Mrs. Tobakias for my half of the rent so that I don’t get charged next week.’

‘Why are you in Dorking?’ Natalie repeats. ‘You’re not doing what I think you’re doing?’

Sinead squeezes her eyes shut. ‘Got to go. Love you, bye.’ She ends the call and sinks her head against the telephone screen. She opens one of the water gallons and slurps as much as she can manage by tilting the heavy container to her mouth. The cold water shocks the spot in her teeth that has been worrying her.

She walks the miles back to her camp. The road is narrow, twisting, rising and dipping over the gentle hills. Passing cars could almost clip her arms swinging the water jugs. She steps into the narrow gutter a few times or scrambles up a steep bank to let a large lumber-carrying truck past. The drivers raise a polite hand to her in thanks. It is generally a friendly place, just not one built for one on foot. Who is poor enough to walk here?

She does not take the same route back in case anyone begins to recognise her around the area. This time she cuts through the woodlands, damp from recent rain, and the mud sucks her boots into the gelatinous, yellow paste. Overhead a woodpecker raps against an oak. A pair of sparrows flutter out of view as she snaps her way through fallen twigs.

She saw a goldfinch several weeks ago when she was feeling disheartened and nearly ready to bundle up her camp. It was that night that she heard the Mercedes roar from its garage and screech down the country road. The house lights were left on. Sinead scrambled up her tree in the dark, barefooted, her feet pierced by bark.

The Lady was standing in the bedroom window looking out at the woodlands. From the steep angle, Sinead could not see the bed or the rest of the room, only the Lady from the waist upwards.

The Lady was crying. Despite the light behind her, her shoulders were shaking heavily. Her chin was practically to her sternum and her hands were locked at the back of her neck, forearms pressed tightly against her chest.

She withdrew for an instant and when she returned, she opened the bedroom window and hurled something out onto the lawn below. The window closed and the Lady disappeared out of sight again.

Sinead dismounted the tree, landing on her feet and then knees. The impact stung her joints, but she scrambled to the back gate, just behind the camera’s eye, which pointed sharply downwards to the gate’s entrance, as if obsessively glaring at an invisible doormat. She peered between the gap between the hinges of the door.

Whatever was launched into the garden, it swivelled in the air clockwise and landed on the ground like a frisbee. It was pigeon grey, with a soft blue light flashing to one side. Sinead shone the torch from her pocket across the lawn, just for a moment. The beam of light caught the object, now visible. Circular – no, donut shaped. But thin.

She recognised it. A Somnus XE7. Retail price, £399.

Why did she fling it, for it to be ruined by dew? A light on the ground floor turned on, and Sinead hastily switched off her torch. The Lady appeared in the living room and unlocked the French doors. An alarm whistled and she punched her fingers against the unseen side of the wall, presumably to disarm it, because the noise abruptly stopped.

She glided across the lawn in her white robe, clutching it closed to her breast. Sinead could hear her breathing, sharp and shrill. The Lady located the device and sighed – perhaps with relief? – and her breathing slowed.

She wiped the Somnus with her sleeve and carried it into the house, resting on her palms like a dead bird. As she turned to close the French doors, the living room light caught her face, and Sinead saw her furrowed, anxious brow. Her shoulders were bent, heavy. This was a resigned woman. This was a defeated woman. Returning to her aviary.

I know you, thought Sinead. I won’t leave you.

Δ

The public footpath snakes between two empty fields and then ends at the junction of a public road. Temptation gets the better of her, and she walks leftwards, down the road past a wide, electric gate hugged between two enormous rectangular pillars. Hound Hall declares a shining plaque. As if that was not austentatious enough, two stone bloodhounds sit poised to attention on each pillar of the gate. Her nose crinkles seeing them again. So subtle.

The stone guardians came with the property when it was purchased three years ago. It’s just surprising they remained – could anyone actually like them?

Sinead is unable to take her eyes off the house’s brutal asymmetry and feature floor-ceiling windows. Two shoeboxes of concrete and glass stacked precariously. The bust of another hound guarded the chrome knocker on the front door. The idea that anyone would need to knock after gaining entry through the draconian security gates seemed odd.

But this sleepy Surrey village was full of contradictions. Loud signs declaring ‘Beware of the Doberman’ while a plump Yorkie yips along the fence. Front gates only a metre high containing elaborate security keypads. Electric doorbells pointing away from the open shed offering £1 for a dozen eggs – honour system. They were optimistic, but paranoid. Good fences make good neighbours. Longing for the comradery of their father’s generation but also fearful of the present, as the Daily Mail tells them to be.

A voice interrupts Sinead’s thoughts. ‘Would you like some mint?’

She stops in her tracks. On the other side of the barred fence is the Lady, on her knees in front of a tidy flower bed running the inside periphery of the front fence. She wears yellow gardening gloves and a wide sun-hat. She holds a pair of pruners and wipes her brow with her sleeve.

‘Sorry?’ says Sinead, surprised.

‘It’s turning into a bit of a hedge and I feel sad hacking it back and letting it go to waste. Would you like some? You could make some tea.’

Sinead looks at her earnest face, and the beads of perspiration forming near her eyes. She has never seen the Lady this close. It is unnerving, like examining an impressionist painting familiar only from postcards. She has never imagined how the Lady’s eyes were coloured. Now she can see they are brown, with a touch of green by the irises.

‘Thank you,’ says Sinead. ‘That would be very nice.’

Observer effect, she thinks, disturbance of an observed system by the act of observation.

The Lady passes a bushy stem through the barred fence to Sinead. ‘Here, take some more,’ she adds, passing more, one by one. They both laugh politely at this slow activity. The slats brush against the mint, releasing the fresh oils into the air. Sinead’s mouth waters, thinking about chewing the leaves. She had been without toothpaste for at least six weeks. It could explain the toothache.

‘Do you live around here?’ asks the Lady.

‘I’m renting,’ Sinead says, having practised this explanation in her head many times. ‘A shepherd’s hut in one of the North fields.’

‘Oh, how marvellous. For how long?’

‘A few weeks. I’m working on a novel.’

‘Goodness. Well, I hope the village is inspiring for you.’

‘It is. How long have you lived here?’ Sinead already knew the answer.

‘Three years. Or thereabouts.’

‘With a partner? Husband?’

‘My husband. He works in the city but he – we – always wanted to live in the countryside.’

‘Is your husband nice?’

The Lady begins to smile and laugh, but then notices the intensity on Sinead’s face, the ferociousness in her eyes. The Lady does not know why, but it is in discord with the innocence of the question. Her smile lowers in.

‘Yes,’ the Lady says. And then the smile suddenly flickers on again like the revved engine of a hotwired car. ‘I should get out of the sun now. It was nice meeting you.’

‘You too,’ says Sinead, and watches the Lady take her basket of gardening tools inside the house.

Sinead picks up her water jugs again and walks back to the road. Once she reaches the end of the fence, she drops one jug to the ground and strikes her face once, twice, three times with an open palm. Stupid stupid stupid. She frightened the lady with her rough questioning.

The fence ends, and the woodland begins again. A narrow stream trickles out of the roots, twisting into a gutter and disappearing into a culvert pipe under the road. She steps onto the bank of the stream, and follows the void of trees until she reaches the end of Hound House. Then, it is a sharp ninety degrees through a thicket of young saplings and trees until she reaches her campsite at the back of the house.

The jugs were heavy and the stream battered her with every step. She should eat, but she does not feel like she deserves it.

Δ

Twenty hour shifts. Sixity days until the funding from their private donor ran out. They had promised results by quarter-one, and now they had crept into quarter-three. They had moved into cheaper accommodation in the basement of a former paper warehouse. Enough space to rig a sterile lab and operate their £300,000 MRI machine sparingly. No windows or natural light.

The storage cupboard was converted into a shift-room with three rows of bunk-beds. Jack woke the sleeping bodies by turning on the lights and clapping his hands loudly. Come on, you pussies. If I’m awake, you’re awake.

Sinead was the only woman in the R&D team, and it showed. By the end of six weeks she smelt just as pungent as the others, and she stopped blanching when she walked past the blow-up sex doll by the watercooler, with a rotating A4-printed face of various celebrities and politicians. When Davidson pretended to hump one of the subjects in the MRI machine, spanking the air above the sedated body, she did not laugh with the other boys in the control room. But she also said nothing.

The lack of sleep and poor, freeze-dried noodle diet had caused her to gain a stone, which she hid under baggy band t-shirts and sweatpants, which seemed to be the dress-code anyway.

And driving her unwavering momentum was the desire to impress Jack. One evening – or perhaps it was so late that it was early – they were hunched over a Mac together, rerunning the analysis code for the umpteenth time, and Sinead finally spotted an errant parenthesis in row 74 of the R code. Jack put his arm around her shoulder and squeezed her against his chest. She was conscious of not having showered in two days, but she knew that he was admiring her mind, not her body, which was a greater intimacy.

I knew you were brilliant.

And Sinead beamed.

Before she could dismiss it with the trained modesty instilled in all young women, he kissed her fully on the lips. The bunks were all occupied, so they got into his car in the parking lot and fumbled under the glow of the streetlight like a couple of teenagers.

Δ

She moved her bags into his office. They shared the single mattress on his floor, tucked between the file cabinets and his desk. No bottom sheet, only a thin duvet and Jack’s chest to keep her warm. The entire floor kept at a chilly 14ºC in order to offset the heat of the servers which lined the hallway.

At first it feels cosy, working next to Jack, their laptops back to back. Sharing gastronomically questionable take-out from the greasy spoon across the road. He demanded perfection with an urgency that felt like a dizzying rush. Pygmalion effect, he reminded his staff. High expectations lead to improved performance. And all the while feeling like her status in the team had been elevated to queen regent.

The fluorescent lights were always on, and the lack of windows made it impossible to determine day from night. One long night in a casino, with her career sitting on the pass line of the craps table.

Then, a potential investor got cold feet. A marathon of an ethical review application failed. A successful reduction in symptoms for a volunteer with treatment-resistant depression – their accountant, Henry – but an inability to replicate it with five more volunteers.

Jack bristled when Sinead placed her arms around him. When she closed her laptop and lay down on the mattress to close her eyes, Jack would exhale sharply. By all means, get your beauty sleep. I’ll just be over here trying to save the company. She would rouse herself and make them more instant coffee with hot water straight from the tap.

Days blurred together. Punctuated only by minor milestones of progress. The rest of the team began to resent her for perks they imagined her getting. They distanced themselves from her, she and Jack becoming isolated in an echo chamber. He made paranoid assertions about the team, and wielded them against her as well when she did not agree.

When she slept – for the few precious hours when Jack was off presenting to investors or haggling for new equipment – it was a putrid, dark sleep. She felt like a seagull doused in oil, unable to move or breathe. Rousing herself was becoming more difficult as she went for longer and longer stretches without.

Sometimes, she would be woken from this cavernous sleep to the feeling of Jack’s mouth on her neck, his hands pawing at her sweatshirt. Unsure if it was morning or night. You can’t get enough of it, can you, he would grunt. His body began to repulse her, and he noticed. This made him bolder, wanting to force his way into her like a mole sensing a coming frost. His kisses became sloppier, his fingernails catching on the folds of her skin. He pounded into her with a desperation bordering on a scream.

Δ

The world has a breath. The swell of grass in the breeze. The hush before rain, inhaling, and the spurt of life in the exhale. This is how we learn to count: in and out.

The darkness creeps over her tent. It seeps in her bones – the cold, the futility. The day has circled back to eat itself. She must be fierce, she must warm herself with her resolve, even as she hugs her knees to her chest and coughs with the damp crawling down her throat.

She is the fearful watcher, the unwinking. sentinel. Often she awakes, sitting upright, not remembering what impulse had hinged her body so forcefully. She wakes holding her foam earplugs, despite having wedged them in her ears an hour ago – what was she trying to hear? Or was it in a dream?

After midnight, awake and trembling with cold, she emerges from her tent. The ivy rustles underfoot. The house is dark, with black eyes. Staring at the house feels insidious – like gazing at the black water at the bottom of a well, tipping yourself forward and daring gravity not to seize you and smash your face into that cold, foetid water.

She imagines his clammy hands around her body, clutching her frame like ivy smothering a house. Trying to soften her angles and the tension of her bones. She was moist when he wanted her to be, and soft when he wanted her to be. She was naked – but more than naked. Peeled. Skinned.

She remembering how she buried deeper within herself to escape. Pulling her elbows in towards her body, squeezing her legs together. His flaccid wetness against the back of her thigh. It might as well have been a hook, having pulled something deep and solemn out of her, and left to shrivel under the cold, fluorescent lights.

Don’t sleep, she had thought. Don’t leave your body. You must keep watch.

And a part of her does want to leave, to sink into a warm, velvet pool away from the body that failed her. But sleep is surrender. Not just to yourself, or to the dark waves of your unconscious that can cast any number of terrifying shadows, but you also must surrender to whatever surrounds your hollow body. The air, the sheets, and whomever you lay beside. You are absent, you abandon your meat suit. Every night.

The body and the mind are an unhappy marriage. How can the body forgive the mind every morning? The mind says: I’m sorry, I left you with Him. I had to go, I had to leave – because I could. You would have done the same.

‘And what did she do?’ you are asking yourself. ‘When does she put her hands up and leave?’ But the truth is that she hated herself for being repulsed, unable to take the intensity that he flung at her. Most women are raised to never disappoint – a worse sin than being stupid or lazy or cruel. She was no different. And she was frightened of making him angry or sad. She feared his intensity could backfire, like a loaded shotgun and destroy them both.

One night sitting in their car, he unfastened the glove compartment and showed her the loaded Glock he kept ‘for protection.’ Her first thought was not ‘I am a strong, independent woman who deserves better.’ It was, ‘I don’t want to die. Say whatever it takes to keep that thing out of his hands.’

The world consists of facts, she tells herself, rubbing her arms for warmth. We are stuck between the cosmos and the atoms. With enough time, all effects can be measured. All truths are revealed. She must observe and quantify.

She can feel the invisible weight that she must drag behind her everyday. If she can prove it real, then she can prove the pain to be real.

The prospect of disproving her hypothesis is frightening. Did she have the wrong subject? Could her variable not have a measurable effect on her subject? Illusory correlation: perceiving a relationship between variables even when no such relationship exists. Cum hoc ergo propter hoc. After all, three hundred scientific papers were published about N-Rays which amounted to be nothing but a fictional phenomenon created by experimenter bias. And astronomers once believed a planet Vulcan orbited next to the Sun, drawing Mercury into its bizarre dance.

This research is cauterisation, an exorcism, she tells herself. A course of antibiotics stronger than radium. Strip the marrow – suck it dry. She read that the body replaces all its cells in seven to ten years, but this seems like a lie. What of the parts of him she swallowed? Did they become part of her muscles and bones? She shudders and wants to tear her veins apart, unspool them like yarn.

Sinead knows the Lady. She was the Lady. She knows where she goes when she sleeps, and she knows what remains, defenceless and silent.

Δ

Her fingers are numb, they feel as stiff as chopsticks. Her mouth throbs. She takes out her torch and shines it between her gum and lower lip. The reflection of her Swiss army knife reveals a black cross on the surface of her left premolar. She wonders if she could scrape the decay out herself. Risky, if it has penetrated the root. She swirls more water around her mouth and swallows.

In the morning, the pain is worse. The gum is puffy. Her neck lymph nodes are swollen like robin’s eggs. She can barely swallow. She does not want to have to return to the shops two days in a row. But she needs paracetamol. Maybe some Bonjela will tide her over. Help her get back up in the tree.

She changes her shirt and ties a bandana around her hair to look as different as possible. She adds a pair of sunglasses to the ensemble. Hopefully someone different will be operating the shop this morning. She exits her patch of woodland and takes a shortcut across a sheep field, shortening the journey by two miles.

When she turns the corner in the village, there is a police car parked outside the petrol station, a policeman leaning on the bonnet. She lowers her head and decides to walk past discreetly. Then, the door opens, and Natalie steps out.

‘That’s her,’ she says, flapping her hand to get the policeman’s attention. Natalie lunges towards Sinead and embraces her. ‘Thank God, you’re okay.’

The policeman approaches and Natalie lets go. ‘Sinead Simon?’ he says, ‘We’re here to check on you. Your friend was very worried about you.’ He approaches with his palms facing her, like she is a bridleless horse about to bolt. His partner emerges from the shop and flanks her. She feels constricted, trapped.

‘Do you want to have a seat?’ says the first policeman. ‘And we can have a chat?’

‘Not really,’ says Sinead.

‘We just want to check if you’re okay.’

‘I’m fine, really.’

‘Where are you staying?’ asks the second officer.

‘Glamping,’ she says. The policemen exchange glances.

‘Your friend is concerned you’re not taking your medication.’

Sinead laughs, unsure why. Raw embarrassment perhaps. ‘I only took those to help me sleep,’ she says, frustrated by the need to reveal personal information.

‘They’re antipsychotics,’ Natalie stage-whispers to her.

‘Also prescribed for sleep disorders,’ declares Sinead, now realising she has raised her voice. She threads her fingers though either side of her hair. This isn’t happening. If only she could let her body float away with her mind like the basket of a hot air balloon.

‘Your friend is worried you might be a danger to yourself or – perhaps it would be best if you came with us to a hospital and we could get you checked out.’

‘What are you doing in the area?’ asks the second officer. Clearly the bad cop.

‘Hiking,’ she says.

‘You wouldn’t happen to be visiting a Mr. Delaney, would you? Or staying nearby?’

Sinead glares at Natalie. She never should have told her.

It had just come tumbling out of Sinead’s mouth when Natalie had found her trying to toast and butter a Wheetabix at four in the morning – having been awake for three days and stoned for two of them.

‘Is that the guy?’ Natalie had asked, pointing to the open copy of Fortune magazine on their kitchen table. The face above the headline, What’s next for Mr. Sandman? had been burnt into a black circle with a Bic lighter, the scorch penetrating into the table.

Sinead had nodded, her shoulders wedged high under her ears. She stood in the middle of their broom-closet kitchen, clutching the counter like a drowning woman clinging to a buoy.

Natalie gently closed the magazine and carried it to the recycling box as if it contained a live spider.

‘Good riddance,’ Natalie had said. But Sinead had read it too many times by now. The words created a scalding stew in her mind, slopping around and around. As Natalie tried to put her to bed, she could still feel them.

Wunderkind Jack Delaney will return to the UK after four years in silicon valley. On the eve of his company going public, with a £5 billion valuation, ‘Mr. Sandman’ has opened a new head office in East London’s Tech City.

‘It’s a far cry from our humble broom–closet in Shoreditch,’ laughed Delaney, referencing the start-up which discovered he and his team discovered the revolutionary method for administering delta-waves in order to guarantee sleep within 3 to 5 minutes. What Elon Musk recently described as ‘The biggest disruption to the tech market since the iPhone.’

‘I wouldn’t go so far as saying “discovered.” It was a happy accident,’ explained the Oxford alumnus. ‘We realised that when we administered delta-waves to participants as part of our mental health study, they were falling asleep – and staying asleep – until we turned off the wave machine.’

Last month’s study in the Lancet revealed that with the Somnus™, the quality of life of shift-workers has risen dramatically.

‘In a 24-7 world, we should be able to control exactly when we need to sleep,’ said Delaney. ‘Doctors, pilots, bus drivers, coal miners … now able to get the rest they deserve and wake up refreshed whenever they are needed. No more insomnia. And no more health problems associated with circadian rhythm disruption.’

The Somnus™ will be released a new, 200 gram lighter XE edition, available in a choice of colours, by Christmas.

When asked whether he uses the Somnus himself, he said, smiling, ‘No, but my wife can’t get enough of it.’

Natalie knew that Sinead was lying when she said she was going on a research trip – for what kind of research does a Boots Pharmacy send its junior pharmacy technician? It hurt to lie. Natalie had been a good flatmate, kind and quiet. Probably the longest relationship Sinead had ever had.

But right now, standing a metre away from two armed policemen, Sinead is a canister about to blow. She is the sharpness in the eye of a cottontail.

She nods slowly, and pretends to take off her backpack from her shoulder. Then she flings it in the direction of the policeman – assuming the surprise would give her a few seconds – and she bolts down the road.

She knows these back gardens better than them. She darts right over a low fence and snakes through an orchard, and over another fence. She veres left and meets a public footpath that turns sharply and intersects a farm road. She whips off her bandana, and throws it leftwards up the path in an act of misdirection, and then sprints in the opposite direction. She hops a cherry laurel hedge – one of the houses advertising a dog despite not having one – and lies flat with her belly against the lawn. She waits several minutes, listening for the sound of running footsteps.

Δ

Your voice is too pitchy in the mornings. The coffee is too cold – make it again. You’re sabotaging me. You don’t believe in me. Corporate espionage. What is that car outside doing? Write down the licence plate – I shouldn’t have to ask. You are empty. You were nothing before you had our goals – look how far you’ve come. I’m proud of you. You challenge me. It’s okay to disagree with you. Are you being intentionally dense? Are you trying to get a rise out of me? I just want to fucking relax. Kiss me. Like you mean it. You’re so hot. Turn around. Come on. You can’t get enough of it.

Δ

Sinead and the Lady. Two data points – that’s a line. Plus time – that makes a vector. She never liked vectors at school. They made her queasy with their untidiness. She preferred natural logs, which felt like launching a kite on a string and then pulling back to the ground. Doing and undoing your work, safely on a string. The laws gave you a path to follow and they held you safe.

The lawn grass tickles her face. She watches the slug trail on a dandelion glint in the sunlight. In the distance, she hears the sound of pounding feet approach, along with the static and consonantless word-garbage from a shoulder radio. Then the noise trails away into nothingness.

Slugs are just wriggles of muscle, she thinks. Perhaps she’s delirious from her sprint on an empty stomach, which is now pressed uncomfortably against the ground.

But from this angle, everything seems connected to grandmother Earth. Some creatures are capable of peeling off her skin for a moment, but always return to the bosom of her gravity. The hare leaps, the mayfly zips, the fox pounces. Natural arcs of creation, destruction, and recreation. Man is the only creature to struggle against this natural concept, and resistance breeds despair. He grieves. He thrashes violently, wanting to seize control of his natural parabula. I am bigger and mightier, he says, attempting to cast off the net. And none are more hubristic than scientists. Beating their fists in the dark.

She lifts herself off the lawn and climbs over the garden fence. Back onto the residential road, she zig-zags down the path, onto the public footpath snaking between two fields.

She runs to the front of Hound House and pounds the buzzer with her fist.

‘Yes?’ says a female voice.

‘This is the writer from up the hill – could I talk with you for a second?’

‘Oh, um, what about?’

‘Better in person,’ she pants. ‘It’s about your husband.’

The crinkle of the autocom soothes into a dead horizon. ‘Just a second.’

The longest wait of Sinead’s life. A car passes and she turns to hide her face against the gate, breathing heavily. She is compromising the experiment. She’s sticking a finger on the scale. But she cannot imagine leaving this valley without knowing.

The Lady emerges from the front door. She looks flummoxed when she sees Sinead, who is still panting hard, her nose and cheeks flushed. The Lady keeps a wary distance from the gate, her arms holding another cream cardigan closed.

‘What’s this about?’ she says.

Sinead swallows. ‘I knew your husband,’ heaving the words from her body like stones. ‘He was cruel. He was a monster.’

The Lady looks bewildered, as if Sinead has just slapped her.

‘I need to know whether you’re safe,’ says Sinead.

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Are you safe? With him?’

A car engine builds to a crescendo behind her and screeches as it cuts the corner of the road and comes to a stop on the driveway. It honks twice, rudely, attention-seeking. Sinead flattens her back against the fence as the horn ornament comes into view.

From the black Mercedes emerges a tall man, chestnut hair, a pale beard trimmed to sharp perfection along his cheekbones. He’s wearing a navy suit and paisley shirt with no tie, just a baby-blue pocket square. He is shorter than Sinead remembers.

Darling, He says to the Lady, leaving the car door open and the car purring. He reaches into his breast pocket and pulls out a mobile phone. Get away from the gate.

‘What is going on,’ says the Lady, frightened.

There was a message from Surrey Police waiting for me at the office. They wanted to do a wellness check and something about a former lab assistant stalking our house. So I came right back.

Sinead wants to curl inside herself like a snail. She presses her back against the bars. A terrible anachronism stands before her. Beneath the crows-feet and greying eyebrows she can see the outline of the young man she used to know.

‘Stay away from me,’ is all she can manage.

‘Do you know her?’ the Lady asks her husband.

No. He raised his phone to his ear. I’m calling the police.

‘Tell her about the mattress in your office. About the hotel room in San Francisco,’ says Sinead. ‘And the Ambien you gave me for jet lag.’

She’s crazy.

He grasps her arm and flings her in a sharp arch away from the gate. She stumbles to the driveway on her knee and then hip. She is infantilized sitting on the crazy-paving, her arm aloft in his tightening grasp. She looks up at the underside of his chin and the softness of a belly spilling over his belt. She sees the echo of a body she used to know – like a soldier staring at his own severed limb, watching the fingers twitch.

‘Listen to me – listen to me,’ Sinead says, twisting her body to grasp the bars of the fence. ‘Elizabeth – Dr. Elizabeth Marjoribanks-Delaney. I know you. If you need help – if you need to get out – when you need to get out, I’ll be here. I’ll be here for you. You’re not alone.’

Sinead’s eyes are watering, begging Elizabeth to see the sincerity. Recognise her reflection.

Then Elizabeth looks towards her husband. ‘How long until the police?’

The light in Sinead flickers out. The planet Vulcan shadows her face. You can observe phenomena, watch a brain shrivel – it’s another thing to try and intervene. That takes years of clinical trials. And this trial has failed.

Prospect theory: a loss is perceived to be more significant than the equivalent gain.

Sinead walks her hands up the gate bars until she is standing, Jack’s hand is still on the arm of her jacket, leashing her. He is speaking the address into the phone in his palm. She thrusts her elbow into his chest, unstabling him for an instant, and then sprints down the driveway as soon as his grasp releases her sleeve.

She runs until her lungs sour with the metallic taste of blood. She runs until her gasping breath smothers the sound of her weeping.

Δ

Natalie parks the Prius in the driveway leading to a field of black-nosed sheep.

‘Just here?’ confirms Natalie.

Sinead nods, removing her forehead from the passenger window. ‘Thank you for doing this.’

‘I don’t like helping you violate an injunction.’

‘We won’t have to get that close,’ says Sinead. ‘Ten minutes, I promise.’

Natalie does not protest, considering the value of the items left at the campsite and the back-rent that Sinead owes. She takes two Ikea bags from underneath her seat and shakes them out. It’s been two weeks since Sinead left Hound House and walked aimlessly into evening, eventually following the signage to Gatwick. She spent the last dregs of her savings on a night in a hostel. And in the morning, she called Natalie, who quickly borrowed her brother’s Uber vehicle.

They cut across the field, and turn left into a thicket of ferns, Sinead leading the way. When they reach the familiar pocket of woodland, Sinead catches sight of her green tent. She tries not to eye the wall behind it, imagining it to have a piercing quality to her eyes like the sun.

The wind or a curious animal has managed to unzip the tent, letting rain flood the base. Together they begin to pack the remains of her campsite. Her gas-stove, binoculars, good wellies, cutlery, and pans. No sense leaving them to rot and litter what countryside we have left.

After Sinead has dismantled the tent and tucked the frame parts into the Ikea bag, she stands and wipes her hands on her jeans. She allows herself to properly look at the fence. Slowly, she approaches.

Natalie is rolling the sleeping bag into a soggy roulade. ‘That’s not twenty feet,’ she warns.

‘Give me a second.’

Sinead creeps to the gate. There is something thrusting from the gap between the door and the fence. Something green upsetting the smoothness of the wall.

There, resting on the hinges of the gate, is a bouquet of mint stems.

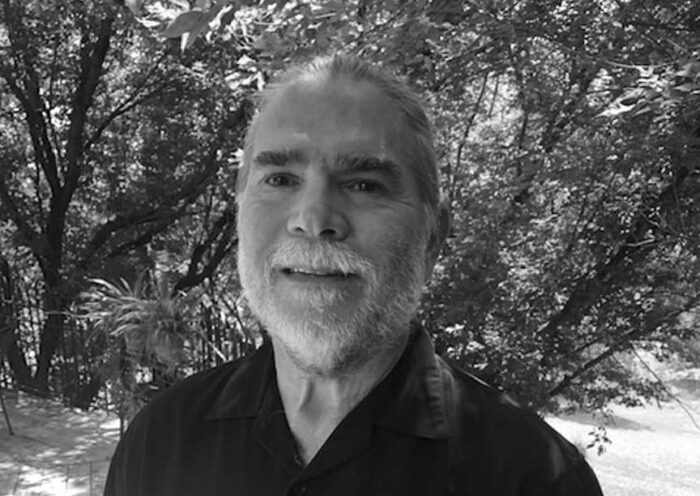

BIO

CL Glanzing is an international nomad, currently living in London. By day, she works in healthcare research, trying to use those ridiculous letters after her name (MA, MSc, PhD). By night, she does heritage crafts and runs an LGBTQ+ bookclub. Her story “Fishbone” was recently included in Issue 51 of Luna Station Quarterly.