The Garden

by Leslie Boudreaux Tidwell

Thoris lay in his favorite tree and tried to remember his home as it had once been. He closed his eyes. Memories came and went as they pleased lately. On the days when thoughts could be summoned at will, Thoris tried to live slowly, letting each breath be its own morning, noon, and night.

There it was. Now he saw it. His forked tongue flickered on its own, already hunting for supper without him. But for now, his mind was still his mind, and the image of his old, perfect garden washed over him.

__

Everything in the garden–alive or not–had been special. It was how the Master worked. Thoris’ home tree was his favorite thing in the garden. In the morning, bark was green, soft, and new. At midday it was dark, rough, and brittle. Each night its dry branches leaned over and waited to be born again. It had lived hundreds of lives, each one a little different. Sometimes the leaves were greener, or more branches sprouted, or the fruit changed from small and red to fat and orange. Thoris memorized the detail of each life. It was the only thing in the garden that had to die, and he wanted to honor it.

At night, the Master spoke through the pores of every living thing. An instant before the sun disappeared, the garden would erupt with joyful humming. Every piece of creation served as an amplifier for his love. This love never translated to speech–at least not the tongue of the garden creatures. He remembered it as a dissonant, yet sweet song paired with the chattering of birds and the sigh of the woman when she felt sleepy. Sometimes the grass and leaves shivered, but he wasn’t sure if this meant the plants were being spoken through or were answering back.

After that chorus of heavenly noise, Thoris’ tree would die, and he would curl up to sleep, looking forward to its rebirth. He always chose the thickest branch as his resting place. It was the perfect spot to watch the sunrise. In the afternoon, after its leaves had come in fully, it provided plenty of shade for his afternoon nap. Somehow, the wood felt as soft as sheep’s wool.

It had felt that soft.

__

Snapping back to his current life, new corner of Thoris’ mind took hold. Eat. Hunt. Eat. He ignored the command to hunt–while he still could–and plucked a puny piece of fruit from a branch. He nibbled on it slowly, as mindfully as he could, and watched the sky. It was a clear day, but the sun felt hotter than usual. Mice and lizards below him crept through the grass. An urge seized him, and a chunk of fruit came rolling from his mouth. It painted his teeth like bloody flesh.

How effortless it would be with his speed and stealth to creep over and swallow them whole.

His eyes flashed from their normal yellow to black. He shook his head and took another bite of fruit. Drops of dew leapt off the skin as he tore out large pieces to chew. Not only did the fruit taste bitter this morning, but he could only bring the very edge of the surface to his mouth. Most of it would have to be thrown away for the ants, or else he could place it on the ground and roll it around with his nose to reach the middle parts. Thoris could no longer see his shriveling limbs. It would not be long. Within a week, his legs would be completely gone.

Not only would he lose his legs, but he would completely lose the power to communicate with man. That didn’t matter, though, for he had not seen the man in days. He gazed off in the distance, and there stood the mighty creature appointed by their Master as a guard for all eternity. It looked sort of like the man who had been born here; he had once been cloaked in that same light. Unlike the man, this guardian’s eyes were not welcoming; nor were they cruel. They seemed to be made of stone. No newcomers were allowed, and the garden’s old tenants were slowly retreating to the new, frightening world. It didn’t matter anymore where they lived now. The Master’s protection was gone.

Thoris could no longer stand the taste of the fruit. He rolled it off the branch with his nose and watched as one fly after another landed on it. His hunger gone, he waited for clarity to return to him. He tried again to remember the past, ignoring the raspy, cold thoughts that were creeping closer to the center of his being.

He thought about the day the announcement was made. It hissed out of the pores of every being like steam. Thoris remembered freezing in place as that heavenly noise came softly, sorrowfully, from him and every other creature and plant. The leaves of his tree rustled with the sound. The Master had spoken to them plainly. Thoris squeezed his eyes shut so tight that tears came out. Words were hard to remember. He focused on them. Cherished them. He begged them to come to his mind.

“We will try another way. You beasts may stay or go, but you will not hear me for a while.”

“Where are you going, Master?”

“Ask the serpent. The changes to come give me no pleasure, but something must be done. This offense must be remembered.”

“Serpent? Master, how have I offended?”

“It was not you, child. It was your neighbor.”

Thoris’ eyes flew open and flashed black again. His mouth opened in a twisted grin, and another word came to him. It felt similar to the word hunt. Kill. Kill. Kill him.

No. He shook himself so violently that he nearly fell from his branch. He steadied himself and spoke aloud. It hurt his throat.

“Olfrid. Cannot. Kill. Olfrid.”

The withering away of all serpents’ legs, the exile from their home, the fading away of music and thought… this was Olfrid’s doing. Those words, your neighbor, has blossomed into a vision from the Master. A final act of kindness. Thoris concentrated as hard as he could and asked for the vision again.

“If I see it again, perhaps it will stay with me when I am gone. Perhaps I won’t be completely lost.”

__

“The mornings come so quickly,” Olfrid grumbled as he crawled out of his hole. He hadn’t considered the inconvenience of an opening facing the east.

“The morning comes exactly when it must.” The answer came from the tree above him.

“Then why do I still feel sleepy, Thoris?”

“Because it’s time to eat. You’ll feel better after you’ve had breakfast. I was about

to go and pick fruit. Come with me.”

“I’ve eaten fruit with you so many times my teeth are stained red.”

“Such vanity, Olfrid,” Thoris teased. “Come on, the company will improve your mood.”

“If it’s all the same to you, neighbor, I’ll go for a little walk to wake up … get used to the light. Is it hotter than usual?” Thoris looked around and shook his head. Then he descended from his branch and crept away.

‘I suppose I could cover the entrance at night,’ Olfrid thought as he walked away, eyeing the ground for fallen leaves.

The morning was damp and breezy. The grass sparkled and shook as he walked. It was almost too thick to move through. He spread the blades apart with his claws and lifted rocks with his pointed snout in search of leaves. The ground was perfectly clean–not even a speck of dirt out of place. He walked on, moving closer and closer to the end of the garden, to the place where trees got shorter and grass felt drier under his feet. Still no leaves.

Olfrid frowned. He had watched Thoris’ tree shed leaves in the late afternoon. Where did they go after they fell? Did they disappear into the ground? Were they carried away by the ants? Anyway, couldn’t he always climb a tree for leaves? But that doesn’t answer where the fallen ones go… He frowned and lowered his head to think.

The garden was home—a beautiful place. He enjoyed plentiful food, courteous neighbors, and a warm place to live. After a hard rain, he could count on the Master to open up the clouds and blanket him with warmth. The river provided him with cool water but also a place to admire himself. All creatures were proud of their looks, but Olfrid had a feeling that a little extra effort went into the serpents. Their scales were smooth and caught the sun’s light so nicely. He loved to look at himself in the water. His scales were large–much larger than Thoris’. They were a greenish brown with darker stripes wrapped around his body, with the occasional spot of white. His head looked noble, wide and pointed at the jaw narrowing to an upturned snout. His narrow eyes looked serious–the eyes of an intelligent creature. Many lazy afternoons were spent reflecting on these facts.

Olfrid also admired the beauty of his home and the grandeur of the evening song. It made him feel important. ‘Whoever made all of these things wants to speak with me,’ he would think. But the Master never waited to hear his words. As soon as the song was over, so was that feeling. That soft little squeeze near his heart and the buzzing of his mind returned to stillness. Peace. Absolute silence. Was it a satisfying silence? He could not say.

Olfrid’s body twitched again. New thoughts were making him feel uncomfortable, like the itch that came before shedding. But it wasn’t that familiar discomfort. When was the last time he had felt uncertain? Olfrid could not recall. When was the last time a question went beyond ‘where will I bathe today’ or ‘when will I have supper?’

Creatures for miles around might have heard Olfrid’s stomach rumbling, but he could no longer think of finding food. Instead, he spent a good part of the morning watching the treetops. He waited for the wind to pick up and make the branches whip wildly from side to side. Surely just one leaf would fall. Nothing. For some reason, this harmless leaf mystery had birthed questions that would never leave his mind as long as it was working.

‘Why have I never wondered before? About this or anything?’

He wanted to think about it more, to try and remember more about himself. Where had he begun? When had the garden begun? His heart squeezed. Then he felt another new discomfort. His stomach cramped painfully in a way he had never experienced.

‘Better to think about this later,’ he thought.

Berry bushes and fruit trees surrounded him, and a variety of tasty root vegetables were hidden underground. He only needed to scrape the earth gently, and one would appear. But none of these things sounded good to him at the moment. After half-heartedly prodding at the dirt, Olfrid decided to wander closer to the border. Maybe there would be something new to try there. He would put up with this growing discomfort and observe how it made him feel. The urgency was a little frightening but exciting at the same time.

‘I need to find food. Need?’

It was a word he’d never used. The Master used it when he lay down rules. They needed to share with one another. They needed to sleep at night and give the garden time to rest and revive. They needed to stay away from… he could not remember.

Stay away from what?

Olfrid met the stranger at the garden’s edge. He was sitting on a large rock just inches away from the grass, and a violet robe was draped over his gaunt form. Beyond the stranger lay an expanse of orange and brown earth with a few scrub bushes poking out of the ground. Though Olfrid felt a breeze on his skin, it did not reach the land beyond the garden. None of the sick plants moved, nor did the stranger’s long hair. It was like looking at the pictures that the man drew for his woman in the dirt.

The stranger’s head was in his hands, and his shoulders were bobbing up and down. Olfrid recognized this. The man had done this on the nights before his woman was created. The noise was never heard in the garden after that, but he remembered what the Master had named it.

“Why are you crying?” Olfrid asked.

The figure startled. Then, after a pause:

“I am crying because I have no home.”

“How terrible. Would you like to live in the garden?”

“That garden is not mine,” he said.

“But it could be yours as well. There are creatures like you here.”

“They are not like me,” muttered the stranger.

“But they are. They walk on thick legs. They have fur on top of their heads. They talk loudly and have long fingers,” Olfrid wiggled his own stubby fingers to demonstrate.

“Can they fly?”

“Why, I’ve never seen them fly.” Olfrid reared back on his hind feet, staring at the man with interest. “Can you fly?”

“I could once,” said the stranger, touching his shoulder tenderly.

“What happened?”

The man turned away from the serpent, refusing to speak. Two holes in his robe revealed the parallel scars on his back. Olfrid cringed at the shapes which did not seem to belong. The wounds gave off a foreign stench, and the edges were moist and sticky. At that moment, Olfrid realized the stone he had been sitting upon was also red. This substance looked like berry juice, but it smelled like something else. It smelled like Thoris’ tree at the end of the day, like the end of life.

“Those marks are not good,” Olfrid said, though he could not say why.

“No. I had wings there once. They were ripped from by body and torn to pieces.” The stranger returned to softly sobbing.

“Who did this to you?” he asked, taking a single step forward.

At this, the man snarled and stared greedily at the garden. “The Master of your home did this to me. The tyrant. He saw my power and ripped it from me.”

Olfrid stepped away from the man and his venomous words. He had heard from the Master that lies were a like a disease. The stranger in violet scoffed at this reaction and looked down upon the animal.

“So he’s fooled you as well.”

“Quiet!” said Olfrid. Don’t you know he can hear everything?”

“I do know. Doesn’t that frighten you? How can you abide someone rattling around in your brain?”

“I’ve done nothing wrong and have nothing to fear. But if he hears you lying—”

“He tolerates lies,” the stranger leaned closer, clenching the parched earth. “What he hates is the truth.”

“The master only wants us to tell the truth,” Olfrid recited.

“We can only tell what we think is the truth. If the real truth is never given, we can claim innocence, even if what we say is a lie.”

Olfrid fell back on all four legs and lowered his head to the ground. He frowned. It was a strange feeling when words made sense in his mind but felt bad to hear. Stranger still, the words reminded him of his own worries. His stomach churned.

“Don’t be afraid, now. I have learned many secrets,” he crept closer now, inching toward the grass but never touching it. “I could tell you the truth about your Master—about many things.”

“You—You’re a bad creature! That’s why you’ve been punished!” And with that dismissal, he ran away as quickly as he could.

__

Thoris felt ashamed. He had stumbled upon this conversation during his morning walk. He could have stopped his neighbor. I didn’t know it was my responsibility, he said, knowing that the Master would hear but would not answer. He had gone home with a resolve to speak up if he saw the stranger again–to protect his friend Olfrid from the dangerous words of this intruder. But the pleasing sights and sounds of the garden had distracted him. That evening had been so lovely. He thought of that time while his memory still functioned.

__

A flock of white cranes made elegant shadows against the canvas of dusk. A black female serpent crossed his path–one with whom he had hoped to mate. She chose a smaller male with shiny yellow scales that rivaled the sun. They still smiled at one another and behaved cordially. There was no need for jealousy in this land filled with gifts. If he was meant to have offspring, the Master would also provide a companion for him. Perhaps the black serpent didn’t enjoy berries and the evening music as much as he. Perhaps the Master would mold a sweet and friendly creature from his own claw or one of his scales, much like the human’s mate.

Thoris loved the woman. Some days were veiled in vague feelings of contentment, but her birth was as clear to him as the first day he felt breath rushing into his lungs. He recalled her immediate affection and curiosity for everything around her. Her first question to the man was about his favorite place in the garden. The man obliged, taking her hand and walking her to a brook filled with silvery fish and swaying reeds. She scooped up her first mouthful of water and laughed her first laugh, unable to contain the fullness of those first moments. Then they walked together, reviewing the names of things. Unsatisfied with calling every serpent ‘serpent,’ and every deer ‘deer,’ the woman moved her mouth around to get accustomed to her language. Then she named them–she gave every creature a second name so they could be more like her and the man. Thoris cherished his name and the love he received from the woman.

There was so much to be grateful for and so much to do, Thoris thought as he climbed the dry, peeling wood of his dying tree. The leaves fell and curled themselves tighter and tighter until they were nothing. But he did not notice this. He was too busy reveling in the song and smacking down the last of his berries. Tomorrow would come just at the right moment, and he would go about his normal day. And there was something else that he would do. Something very important. What was it? Well, no matter. He would remember, precisely when he was meant to.

The following morning, Olfrid and his new companion were debating again. Thoris had forgotten his task and was far away, making the woman laugh with a song about beetles.

__

“Again you call me a bad creature,” the stranger rolled a stone between his thumb and forefinger, sounding very bored. “It is not bad to oppose slavery.”

Slavery. It wasn’t a word that anyone in the garden knew. The part of Olfrid that loved the Master begged him to run away, to find a branch in the cool shade and never think of the stranger again. But instead he allowed a trance to take him. Slavery. The word made his head ache a little. The sound left a foul incense around him. It sounded as wicked as a lie.

“What is that?”

“Slavery?” The stranger flicked the stone away and spread his arms wide.

“Slavery is this garden. Slavery is what keeps his voice in your head. I know, because I lived by his side. I have seen what you’ve never seen.”

“You’ve seen the Master?”

“I have. Even when I could not see him, I felt him. There was no rest. When I tried to drive his voice from my mind for one moment—when I tried to remove him from my heart just for an instant, he devoured my strength and cast me out. My old friends chased me from home. Some followed me, but they are even more mutilated and powerless than I.”

“And… their wings are gone, too?”

“No one here may have wings.”

Olfrid didn’t speak for a long time. “You think you’ve been wronged. You think you’ve been punished unfairly. You seem to be truthful. But this is more than I’ve ever had to think of in my life.”

“He’s seen to that.”

“But all he wants is to be near us. Why try and be apart from someone who loves you and provides for you?”

“To know which thoughts are mine!” When the stranger’s voice raised, it sounded like a crackling fire. The air felt warmer around him. “To have one moment’s peace! Don’t you ever wonder? Don’t you ever wish to know which decisions are truly yours?”

“I … don’t think of that.”

“Because he won’t let you.” For the first time, the stranger reached out for his companion. He gripped the serpent’s limb, and Olfrid thought he felt a searing pain upon his scales. When he pulled back, there were no scars, but the sensation remained.

“I can’t listen to you anymore. These are all lies. They’re lies!”

“Talk to the master tonight,” he called as the serpent made his escape. “Don’t depend on my words! Find out for yourself!”

Olfrid crept away, almost free. That night, he could not feel the Master singing through him. Instead, whispers of doubt circled him and kept him from sleeping. By morning, his mind was neither his nor the master’s. The garden’s little pleasures failed to satisfy him as they did when something small troubled his mind. These new worries were so much greater than anything else in the garden—so much greater than a splinter in his foot or a cloud of dirt in his drinking water. It felt like prickles in his chest. Olfrid shifted from side to side until there was nothing to do but sit, and that didn’t help either.

The stars and moon were all pointed at him, staring, asking him questions. What troubles you? Why are you afraid? Whom do you seek?

“Is it true?” he asked aloud.

The lights of the night sky gazed back, unmoved. Olfrid could not remember what the master’s song sounded like.

Every sunset ritual felt as distant as the birth of the world.

“I just want to hear you say it,” he pleaded many nights after. “Just once. Say he’s lying. I’ll believe you. I’ll believe whatever you tell me. Just once. Aloud.”

Olfrid returned to the edge of the garden after days of waiting. The stranger was not there. He stared at the desolation, gently moving one toe towards the wasteland beyond his home. He searched for green in the distance, but there was none. The serpent could not imagine surviving there. Moreover, he could not imagine an offense terrible enough for such a prison. He had nearly disappeared into the brush when a voice emerged from the dead world. There stood the stranger. His robes looked cleaner than before. His shoulders, straight and strong.

“Did he speak to you?”

Olfrid had many questions, but the sick feeling in his stomach told him to run.

“Leave me alone. Stay away.”

“I am away,” he said, sitting down on the same rock where Olfrid had found him. It was also cleaner, the blood washed away. “I thought I made it clear before that I won’t harm you. Now … Did. He. Speak. To. You?

“He … he didn’t,” Olfrid wanted to cry. “It was so strange.”

“And how did you feel?” He clasped his hands together and cocked his head. Listening.

“I felt … covered in mud. Buried.”

“And free,” the stranger clenched his fist, claiming a victory that Olfrid was not sure of.

“I feel sick.” The serpent lowered his head.

The stranger made a soothing, clicking sound with his tongue. Olfrid thought he’d heard an ape make this sound when its baby was chattering and fussing late at night. He drew back but could not turn away from this man who was not quite a man. The words the followed kept him in place.

“It’s odd at first,” he admitted, “but what you experienced was not a bad thing. You challenged him, and he surrendered.” The stranger lifted his arms towards the sky. “You … bested him.”

“He didn’t speak to me because he knows I was talking to you.” It was the first time Olfrid could truly admit his guilt. He stared at the grass–the grass that was still his if he wanted to walk upon it.

“Do not fear him, my little friend. Now that you know what I know, I’ve come to share another secret with you.”

“What can you tell me? I know what you are. You doubted him and so have I, and now he’s sent you to live in a world with no life.” Olfrid panicked, stricken with a new realization. ”It’s what he’s going to do to me. It’s why I can’t hear him!” He threw himself to the ground. If he begged, could he be forgiven?

“No life?” The stranger laughed for the first time. It wasn’t the quiet scoffing sound that Olfrid was used to. His voice was full of excitement. “My friend, you haven’t seen all the corners of my home. I’ve explored it myself.” He pointed out past the dusty hills. “Believe me, there is life. There is food. There is water. There is music sweeter than the Master’s. And best of all…”

Olfrid felt another pull. “What’s the best of all?”

“Everyone there has the Master’s eyes … the Master’s voice … the Master’s mind. Everyone is his own king.” The stranger’s lean arms and long fingers painted an idyllic picture in the air.

“How do I know you’re telling the truth?”

“Unlike the Master, I am happy to show you.” He was leaning towards Olfrid now, his voice small and secretive. “I only need you to help me first.”

Olfrid thought for a long time. He sniffed the air, looked back at the greenery, and waited for a breeze to hit his face. Any sign. In those moments, he gave the Master one more chance. If he is bad, tell me. I’ll believe you. When no answer came, he walked forward, lengthened his neck, and spoke:

“What do you want me to do for you?”

“I am afraid for the man and woman who live here. You can help free them. You

can go where I cannot,” he whispered.

“How can we free them?” Olfrid asked, matching the stranger’s voice.

“I remember when your home was created. The Master warned his children of a place they should never go. Do you know this place?”

“The tree,” Olfrid pointed at the garden, stretching his arm as far as it would go to suggest a long distance. “The one in the center of the garden.”

The Master often sang images of that tree into his creations’ heads. With it came woeful melodies and dark colors. Thoris had nearly chosen it as his home, but its trunk could not be climbed. Though its bark appeared coarse and covered in knots, to an animal it felt as slippery as the slime-covered stones in the water.

“That’s it. I’m sure he never told you why it was forbidden,” said the stranger.

“He only said it would harm us.”

“Why would he put something harmful in your home?” Another question to turn Olfrid’s stomach and make his feet feel restless.

“I never thought about it.” How many times had he said or thought those words recently?

“Think about it now,” the stranger pressed. “Think hard.” Now he was inches away from the serpent’s face. Without realizing, Olfrid had inched closer and closer to the garden’s boundaries. One claw had crossed that line and rested on the stone.

“I don’t know. I can’t. I just… I don’t feel well,” Olfrid said, his head swimming. Suddenly hot and thirsty, he gasped and drew back on his hind legs. The one traitorous claw backed away. The heat of the outside land left him feverish after barely one touch.

“Stay with me!” He reached out to Olfrid. The impatience in his voice might have betrayed the gentleness in his eyes of the serpent hadn’t felt so ill. “Stay strong. I have felt what you are feeling. It will pass.”

“My chest,” Olfrid gasped, a tear rolling down his scales. “Something is squeezing inside me.”

“Yes. It hurts,” the stranger purred, inching closer.

“Why does it hurt?” His legs bent and twisted from the pain. He curled up, his tail close to his snout. He closed his eyes tightly. Does the hurt come in through the eyes? The discomfort of hunger could not compare; it would have felt like a shallow splinter now. Tell me the truth and I’ll listen,” Olfrid begged. Tell me to run and I’ll run. I’ll never return to this place. The stranger watched the serpent’s eyes searching past the clouds, past the sky, past infinity.

“You’re dying,” said the stranger. His words were like a lullaby now.

“What is dying?” The word tasted like that other word. Slavery. Olfrid wanted to rub his tongue in the dirt after speaking it.

“Dying… is what’s inside of the fruit,” he said, stroking Olfrid’s back. The stranger’s hands looked smooth like the man’s but felt like the old bark of Thoris’ tree in the evening, and cold as the morning stream. “You were able to bring yourself to this moment without the magic of the fruit. Few can. Dying is good. It is the end of powerlessness. Your body and soul stops, and then you awaken a king. Like me.”

“I don’t like it,” Olfrid squirmed at the stranger’s touch. He pulled away. “I don’t like it!”

“Take my hand. Now I will tell you. The Master thought for a long time about it—about whether his creatures should have his powers. It was fear that stopped him. If he shared his power, he would no longer be needed. Do you see? Do you see what your Master is now?” The stranger stretched out his hands towards the serpent.

“I don’t like this,” Olfrid repeated, breathing more heavily. “I don’t want this!”

Olfrid had known the stranger for only a few days. In the garden, that was enough time to love someone. This creature was more confusing. He seemed to know when Olfrid felt fearful or uncertain. Was that not like the Master? Didn’t he also know the minds of his creations? But what good was that knowledge if he ignored Olfrid’s pleas? Would the Master ever answer his children’s call? Would more of the Master’s children wake up wondering why they had never wondered before? Or would he be lonely in the garden forever, yawning through conversations of fruit and weather?

What happened next shocked the serpent, because it was so unlike his new companion. The stranger took Olfrid in his arms and cradled him. He suddenly felt as warm as the Master’s song. The roughness of his skin disappeared, or at least it no longer mattered. This was the answer Olfrid had craved. Every caress was an answer to his call for love, for attention, for acknowledgment. I am a living being. I have begun to wonder. Show me that you hear me. Show me that you understand. Answer me. In one motion, the dying creature’s doubt washed away.

“I am with you,” whispered the stranger. “Let the death come. It will soon be over. Then you and I will save the world from slavery.”

“Slavery.” The word made him die faster. “Death… will save me from slavery?”

Now a sweet taste filled his mouth.

“It is the only solution.” Gently spoken, simple answers. Olfrid accepted them hungrily. He relaxed his body and nestled in the soft robes of his master.

Olfrid felt a final spasm in his chest. It spread to his limbs, tail, and head. He felt something like spiders crawling around in his skull. A song rose up from his heart, a terrible song made of shattering and screeching. The noises scraped at his ears and eyelids. Flashes of coherence exploded amid the madness. Words. Lost. Death. Never. Betrayed. Soon, the noise and pain retreated like a wave, and Olfrid opened his newborn eyes.

The garden was as red as his new master’s back. He looked out to the lifeless world and saw a halo beyond the hills that had once been invisible. For a moment Olfrid was sure he could hear music. Different music. Vibrant, straightforward music with rhythm and words. He turned back to the redness and saw Thoris’ head poking out of a bush, but his neighbor looked different. There was a vibrating silver chain around his neck that had never been there–or that he had never noticed.

“What is that thing he wears, master?” Olfrid asked.

“What you see is a shackled beast,” the stranger hissed. Shall we free him as well?” The stranger’s voice sent Thoris running.

“This is slavery? This is what I did not see?”

“This is it, my friend,” he said, petting Olfrid’s head. “You finally see. You will free the man and woman, and then we will claim our kingdom. Go. Go into the garden while you still can.”

Olfrid hopped out of the stranger’s arms and into the tall grass. The ground felt hot, and a dusty wind pushed him in the direction of the dry world. Still, he was able to struggle against the unseen current. Thoris found him bounding out of the brush moments later and spoke to him frantically.

“Olfrid! Olfrid! What did he say? What did he do? What’s the matter with your eyes?”

“My eyes? My eyes and everything else are new. I have been reborn by dying.”

“Re–” Thoris did not know the word. There is only birth. How could anyone be born again? Like my tree?… best not to think about it. “You look the same except… there is something missing when I look at you. I can’t find… something.” Thoris struggled as Olfrid once had, and Olfrid felt pity. “Please. Tell me exactly what he told you.”

“I cannot explain to a beast who has never wondered,” said the newly awakened Olfrid.

The reborn serpent looked into the face of his old friend and saw a stupid animal. Thoris’ words were like the single-minded babble of a stream running towards the open water. The shackle around his old friend’s neck made him want to cry, but then pity turned into disgust. How could anyone be this blind? How had he ever lived like that? He pushed past the beast and ran towards the center of the garden.

__

The time had come. Something like a breeze was pushing all of the creatures out of the garden and into the barren world of punishment. Thoris marched along in rhythm with another serpent beside him, a female. They usually said good morning to one another, but today, he could not find that word. And anyway, her eyes were completely blackened. She is still a good female, he thought. I should find her whenever we settle. I will take her as my mate. Before he could move closer, another, larger serpent came from behind and nudged her forward. For a moment, his anger flared, and the word kill rose up in him.

“I am here. I’m still here. Forgive me,” Thoris said to the sky as he shook the thoughts away. “Forgive me.” He moved obediently with the current with his eyes on the ground. After days of uncertainty, the Master’s wishes were finally being set into motion. Birds flew toward the gray horizon. Trails of insects filed out onto the sand. The wails of the man and woman rang out as their bare feet touched the hot ground. Thoris could have fought the wind that pushed him away. It was more of a whisper than a shout, but he felt he should display obedience. Perhaps there was a chance for forgiveness. And if not… A thought came to him.

“Master, just one more night in my beloved tree. Please.”

The wind pressed on a moment longer, then it stopped, and then it changed direction.

He bowed his head and crept home, plucking a berry here and there. They were bitter and made him feel sick. He could not get to sleep until he vomited them up again.

Other creatures were with him in the night. A wolf paced beneath him as the sun rolled away. It hoped that he would fall from his branch. Thoris had never been hunted before, but somehow he recognized the look of a hunter immediately. I am like you, he wanted to say to the wolf. We hunt. We kill. The part of himself that was disappearing fought back. He listened for the music, for a voice, for the any pleasing residue that could sustain his mind. There was no music, only the rustling of sleepless living things.

When the wolf gave up and prowled away, there came the serpent and a female. They had also decided to sleep in the garden. His female. He had not taken her as a mate, but she knew. She knew that she was his. She knew and he knew, and she is using him to anger you. Show her you are strong enough for this new life.

Thoris woke up with the lifeless body of his rival under his foot. A red river cut its path in the dirt. His female had fled. He licked his lips and felt a quick pain. Slowly and carefully, he ran his tongue around the inside of his mouth and felt something small and sharp. He poked around with his finger, felt a sting, and then curled up his little body.

I cannot stop this? Your desire is for me to kill? Master, I’ll venture to any corner of the world if you’ll save me from these desires. Master, can you hear me?

The mist thickened. He couldn’t breathe without coughing. While words were still with him, he thought of all the ways he could make amends. When an idea came to him, it immediately dissolved into nonsense.

In the morning, Thoris couldn’t wait to open his eyes and watch his tree come to life. He stared at the shriveled leaves and black bark. The sun kept rising, a handful of leftover birds chirped, but the tree would not awaken. In fact, as the sun climbed, the branches bowed even lower. Leaves turned to dust when touched by the wind. The wind. Thoris could not recognize the word, but he could feel it on his back, pointing him towards his new home. His new home filled with hunters, blood, and no words.

Olfrid and Thoris crossed paths many times after the garden’s end, though they didn’t always know. Most days, they reared back and struck at one another with their dripping fangs filled with a death less potent than the stranger’s. On rare days, Thoris could remember flashes of the old times, and he wished he could not. On these mornings, he could only remember his and Olfrid’s last meeting as thinking, speaking creatures:

__

“Where is your friend now?” Thoris asked as he stumbled toward his neighbor.

He was still adjusting to his new body. Olfrid said nothing. “Where are your songs as sweet as the Master’s? Where are your all-seeing eyes?” he demanded.

Thoris trembled at the dead, black marbles inside the slowly emptying head of his old friend. Olfrid slinked away, fixated on something else. He coiled up and watched a nearby mouse who sat bobbing upon a stone, as if thinking of a song. “Olfrid, don’t—” But before he could finish the plea, Olfrid had stricken and swallowed it. Then, with a flicker of his fiery tongue, he slithered away.

BIO

Leslie Boudreaux Tidwell is a native of Lafayette, LA and lives there with her husband, Jake. When she is not teaching third graders or performing in one of her improv troupes, Leslie spends her private time writing and submitting short stories. In the 2019 NYC Midnight Short Story Challenge, she was awarded Honorable Mention for her crime caper, “Jane the Brain.” In her classroom, Leslie prioritizes writing instruction and aims to mold a new generation of authors who are excited to share their work with the world.

Leslie Boudreaux Tidwell is a native of Lafayette, LA and lives there with her husband, Jake. When she is not teaching third graders or performing in one of her improv troupes, Leslie spends her private time writing and submitting short stories. In the 2019 NYC Midnight Short Story Challenge, she was awarded Honorable Mention for her crime caper, “Jane the Brain.” In her classroom, Leslie prioritizes writing instruction and aims to mold a new generation of authors who are excited to share their work with the world.

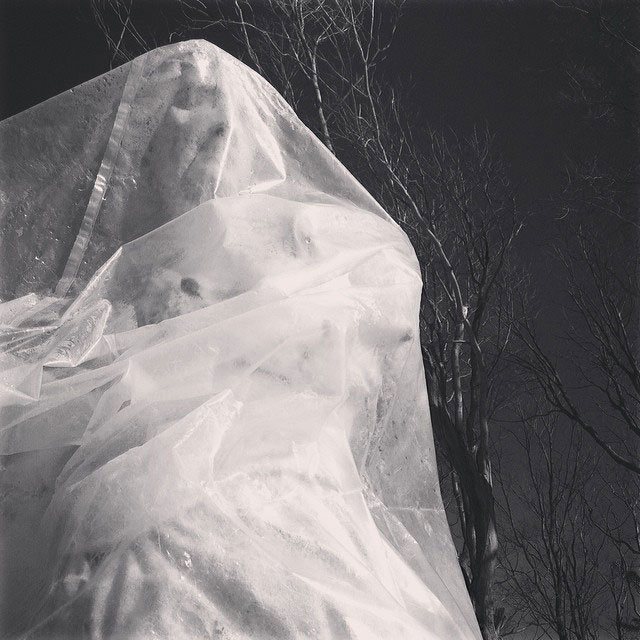

Living in Maine is like living in two places. I spend my days walking circles in the forest, down side streets, and through pocket gardens. In summertime, days pass slowly and the crystal green ocean glistens with falling waves. Deciduous forests cloak winding carriage trails to the Atlantic. In the winter there is only silence. Seaside towns that are so empty even light footsteps echo down their streets. Stone walls that once marked property lines crumble along the forest floor. Nature reclaims the ruins of ancestral homes and resort hotels. By night, dark salt water crashes against seaside cliffs while foghorns moan in the harbor. Three of the four seasons are spent in total isolation. Memories of being submerged in the amber glow of August fall away. Cicadas sing as the days grow shorter, until one morning a fog rolls in to hover above the marshland. I cross the great Piscataqua River by foot. From the bridge I watch its powerful current. Tankers pass along the waterfront with salt, freight, and scrap metal.

Living in Maine is like living in two places. I spend my days walking circles in the forest, down side streets, and through pocket gardens. In summertime, days pass slowly and the crystal green ocean glistens with falling waves. Deciduous forests cloak winding carriage trails to the Atlantic. In the winter there is only silence. Seaside towns that are so empty even light footsteps echo down their streets. Stone walls that once marked property lines crumble along the forest floor. Nature reclaims the ruins of ancestral homes and resort hotels. By night, dark salt water crashes against seaside cliffs while foghorns moan in the harbor. Three of the four seasons are spent in total isolation. Memories of being submerged in the amber glow of August fall away. Cicadas sing as the days grow shorter, until one morning a fog rolls in to hover above the marshland. I cross the great Piscataqua River by foot. From the bridge I watch its powerful current. Tankers pass along the waterfront with salt, freight, and scrap metal.

Donna Vitucci’s stories, poems, and creative non-fiction have been published in print and online since 1990. Her novels IN EUPHORIA, SALT OF PATRIOTS and AT BOBBY TRIVETTE’S GRAVE are 5-star-reviewed. Her most recent novel, ALL SOULS, along with the others, is available through Magic Masterminds Press. A Midwestern girl, she has relocated to the North Carolina piedmont, where she enjoys gardening, reading, walking and yoga.

Donna Vitucci’s stories, poems, and creative non-fiction have been published in print and online since 1990. Her novels IN EUPHORIA, SALT OF PATRIOTS and AT BOBBY TRIVETTE’S GRAVE are 5-star-reviewed. Her most recent novel, ALL SOULS, along with the others, is available through Magic Masterminds Press. A Midwestern girl, she has relocated to the North Carolina piedmont, where she enjoys gardening, reading, walking and yoga.

Paul D. Mooney is an NYC born writer with pieces published in American Writers Review, The Big Jewel, three minute plastic, Task & Purpose, and more. You can see more of his work on his website,

Paul D. Mooney is an NYC born writer with pieces published in American Writers Review, The Big Jewel, three minute plastic, Task & Purpose, and more. You can see more of his work on his website,

DILANTHA GUNAWARDANA is a molecular biologist by training, yet identifies himself, as a wordsmith, papadum thief, “Best Laksa” seeker, poet of accident and fluke, hoop-addict, a late bloomer on all fronts, ex-quiz-druggy and humor-artist, who is still learning the craft of poetry. Dilantha lives in a chimerical universe of science and poems. His poems have been accepted for publication /published in Kingdoms in the Wild, Heart Wood Literary Magazine, Canary Literary Magazine, Boston Accent Lit, Forage, Kitaab, Creatrix, Eastlit, American Journal of Poetry, Zingara Poetry Review, The Wagon and Ravens Perch, among others. Dilantha has two collections of poetry, Kite Dreams (2016) and Driftwood (2017), published by Sarasavi Publishers, and is working on his third poetry collection and a book of haiku poems. Dilantha was awarded the prize for “The emerging writer of the year – 2016” in the Godage National Literary Awards, Sri Lanka, while being shortlisted for the poetry prize, in the same awards ceremony.

DILANTHA GUNAWARDANA is a molecular biologist by training, yet identifies himself, as a wordsmith, papadum thief, “Best Laksa” seeker, poet of accident and fluke, hoop-addict, a late bloomer on all fronts, ex-quiz-druggy and humor-artist, who is still learning the craft of poetry. Dilantha lives in a chimerical universe of science and poems. His poems have been accepted for publication /published in Kingdoms in the Wild, Heart Wood Literary Magazine, Canary Literary Magazine, Boston Accent Lit, Forage, Kitaab, Creatrix, Eastlit, American Journal of Poetry, Zingara Poetry Review, The Wagon and Ravens Perch, among others. Dilantha has two collections of poetry, Kite Dreams (2016) and Driftwood (2017), published by Sarasavi Publishers, and is working on his third poetry collection and a book of haiku poems. Dilantha was awarded the prize for “The emerging writer of the year – 2016” in the Godage National Literary Awards, Sri Lanka, while being shortlisted for the poetry prize, in the same awards ceremony.

Miriam Edelson is a social activist, writer and mother living in Toronto, Canada. Her literary non-fiction, personal essays and commentaries have appeared in The Globe and Mail, Toronto Star and CBC Radio. Her first book, “My Journey with Jake: A Memoir of Parenting and Disability” was published in April 2000. “Battle Cries: Justice for Kids with Special Needs appeared in late 2005”. She has completed a doctorate at University of Toronto focused upon Mental Health in the Workplace and is currently at work on a collection of essays.

Miriam Edelson is a social activist, writer and mother living in Toronto, Canada. Her literary non-fiction, personal essays and commentaries have appeared in The Globe and Mail, Toronto Star and CBC Radio. Her first book, “My Journey with Jake: A Memoir of Parenting and Disability” was published in April 2000. “Battle Cries: Justice for Kids with Special Needs appeared in late 2005”. She has completed a doctorate at University of Toronto focused upon Mental Health in the Workplace and is currently at work on a collection of essays.

STEVEN RATINER has published three poetry chapbooks and his work has appeared in scores of journals in America and abroad including Parnassus, Agni, Hanging Loose, Poet Lore, Salamander, QRLS (Singapore) and Poetry Australia. He’s featured in the new anthology Except for Love – New England Poets Inspired by Donald Hall. The poems appearing in The Writing Disorder are part of a new full-length manuscript entitled The S in Sex. He’s also written poetry criticism for The Christian Science Monitor, The San Francisco Chronicle, and The Washington Post. Giving Their Word – Conversations with Contemporary Poets was re-issued in a paperback edition (University of Massachusetts Press) and features interviews with many of poetry’s most important figures.

STEVEN RATINER has published three poetry chapbooks and his work has appeared in scores of journals in America and abroad including Parnassus, Agni, Hanging Loose, Poet Lore, Salamander, QRLS (Singapore) and Poetry Australia. He’s featured in the new anthology Except for Love – New England Poets Inspired by Donald Hall. The poems appearing in The Writing Disorder are part of a new full-length manuscript entitled The S in Sex. He’s also written poetry criticism for The Christian Science Monitor, The San Francisco Chronicle, and The Washington Post. Giving Their Word – Conversations with Contemporary Poets was re-issued in a paperback edition (University of Massachusetts Press) and features interviews with many of poetry’s most important figures.

Leslie Boudreaux Tidwell is a native of Lafayette, LA and lives there with her husband, Jake. When she is not teaching third graders or performing in one of her improv troupes, Leslie spends her private time writing and submitting short stories. In the 2019 NYC Midnight Short Story Challenge, she was awarded Honorable Mention for her crime caper, “Jane the Brain.” In her classroom, Leslie prioritizes writing instruction and aims to mold a new generation of authors who are excited to share their work with the world.

Leslie Boudreaux Tidwell is a native of Lafayette, LA and lives there with her husband, Jake. When she is not teaching third graders or performing in one of her improv troupes, Leslie spends her private time writing and submitting short stories. In the 2019 NYC Midnight Short Story Challenge, she was awarded Honorable Mention for her crime caper, “Jane the Brain.” In her classroom, Leslie prioritizes writing instruction and aims to mold a new generation of authors who are excited to share their work with the world.

Jerry Tyler is a “Contemporary Classic Writer.” His background ranges from LA Noir to Interpersonal Growth Counseling and is reflected in his style of writing. He is an in demand educator and facilitator for creative writing at Studio 526 as well as a world published contributing columnist in various genres.

Jerry Tyler is a “Contemporary Classic Writer.” His background ranges from LA Noir to Interpersonal Growth Counseling and is reflected in his style of writing. He is an in demand educator and facilitator for creative writing at Studio 526 as well as a world published contributing columnist in various genres.

Mark Tulin is a former family therapist who lives in Santa Barbara, California. He has a poetry chapbook, Magical Yogis, published by Prolific Press (2017), and he has an upcoming book of short stories entitled, The Asthmatic Kid and Other Stories. His stories and poetry have appeared in Fiction on the Web, smokebox, Friday Flash Fiction, Amethyst Magazine, Leaves of Ink, Vita Brevis, among others. His website is Crow On The Wire <

Mark Tulin is a former family therapist who lives in Santa Barbara, California. He has a poetry chapbook, Magical Yogis, published by Prolific Press (2017), and he has an upcoming book of short stories entitled, The Asthmatic Kid and Other Stories. His stories and poetry have appeared in Fiction on the Web, smokebox, Friday Flash Fiction, Amethyst Magazine, Leaves of Ink, Vita Brevis, among others. His website is Crow On The Wire <

George Cassidy Payne is a poet from Rochester, New York (U.S.). His work has been included in such publications as the Hazmat Review, Allegro Poetry Journal, MORIA Poetry Journal, Chronogram Magazine, Ampersand Literary Review, Pulsar, The Angle at St. John Fisher College and several others. George’s blogs, essays and letters have appeared in Rolling Stone, The Atlantic, USA Today, the Toronto Star, The Havana Times, Nonviolence Magazine, The Wall Street Journal, the South China Morning Post, The Buffalo News, Rochester City Newspaper and more.

George Cassidy Payne is a poet from Rochester, New York (U.S.). His work has been included in such publications as the Hazmat Review, Allegro Poetry Journal, MORIA Poetry Journal, Chronogram Magazine, Ampersand Literary Review, Pulsar, The Angle at St. John Fisher College and several others. George’s blogs, essays and letters have appeared in Rolling Stone, The Atlantic, USA Today, the Toronto Star, The Havana Times, Nonviolence Magazine, The Wall Street Journal, the South China Morning Post, The Buffalo News, Rochester City Newspaper and more.

Mateusz found out very early on that there’s a boundless amount of ideas floating just above his head at any given moment. The tricky part was always to pluck one at the right time and gift it with a form it truly deserved. Mateusz works in creative fields as a designer out of Central Europe, and revisits the writing outlet whenever he gets restless.

Mateusz found out very early on that there’s a boundless amount of ideas floating just above his head at any given moment. The tricky part was always to pluck one at the right time and gift it with a form it truly deserved. Mateusz works in creative fields as a designer out of Central Europe, and revisits the writing outlet whenever he gets restless.

Catherine Moscatt is a 22 year old counseling and humanities student who enjoys working at the local library. She plays volleyball, listens to loud music and drinks a lot of lattes. She is passionate about mental health awareness and helping those who suffer from mental illness.

Catherine Moscatt is a 22 year old counseling and humanities student who enjoys working at the local library. She plays volleyball, listens to loud music and drinks a lot of lattes. She is passionate about mental health awareness and helping those who suffer from mental illness.

Casey Killingsworth has been published in The American Journal of Poetry (forthcoming), Common Ground, COG, Two Thirds North, and other journals. He has a book of poems, A Handbook for Water (Cranberry Press, 1995), and a book on the poetry of Langston Hughes, The Black and Blue Collar Blues (VDM, 2008). He graduated from Reed College.

Casey Killingsworth has been published in The American Journal of Poetry (forthcoming), Common Ground, COG, Two Thirds North, and other journals. He has a book of poems, A Handbook for Water (Cranberry Press, 1995), and a book on the poetry of Langston Hughes, The Black and Blue Collar Blues (VDM, 2008). He graduated from Reed College.

Cecilia Kennedy earned a doctorate in Spanish literature and taught English and Spanish for 20 years in Ohio before moving to the Greater Seattle area with her husband, teenage son, and cat. In 2017, she began writing fiction for the first time. Since then, about sixteen of her short stories have appeared in eleven different literary journals/magazines online and in print. She also has a blog called “Fixin’ Leaks and Leeks,” where she chronicles her humorous attempts at cooking and home repair. (

Cecilia Kennedy earned a doctorate in Spanish literature and taught English and Spanish for 20 years in Ohio before moving to the Greater Seattle area with her husband, teenage son, and cat. In 2017, she began writing fiction for the first time. Since then, about sixteen of her short stories have appeared in eleven different literary journals/magazines online and in print. She also has a blog called “Fixin’ Leaks and Leeks,” where she chronicles her humorous attempts at cooking and home repair. (