That Heartbreaking Blues and Other Complications: An Interview with Philip Cioffari

by Bill Wolak & Philip Cioffari

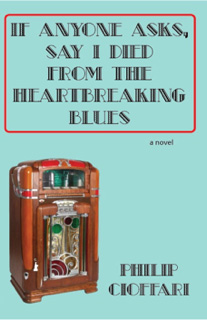

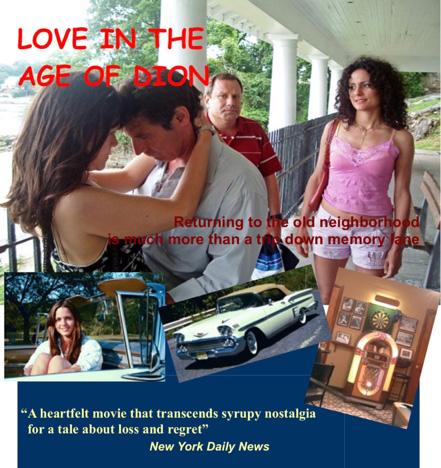

Philip Cioffari’s meticulously crafted stories and novels explode like street racing muscle cars burning rubber at the starting line in search of dangerous fun, holy nostalgia, impossible love, and the exchange of dreams across the back roads of America. Cioffari casts an attentive eye on whatever appears through the wind-shield, but mainly what resonates throughout his work is the uncanny, the off-beat, and the incongruous. He is the author of the novels: If Anyone Asks, Say I Died From the Heartbreaking Blues; The Bronx Kill; Dark Road, Dead End; Jesusville; Catholic Boys; and the short story collection, A History of Things Lost Or Broken, which won the Tartt Fiction Prize, and the D. H. Lawrence award for fiction. His short stories have been published widely in commercial and literary magazines and anthologies, including North American Review, Playboy, Michigan Quarterly Review, Northwest Review, Florida Fiction, and Southern Humanities Review. He is a playwright member of the Actors Studio in New York City. He has written and directed for Off and Off-Off Broadway. His Indie feature film, which he wrote and directed, Love in the Age of Dion, has won numerous awards, including Best Feature Film at the Long Island Int’l Film Expo, and Best Director at the NY Independent Film & Video Festival. He is a Professor of English, and director of the Performing and Literary Arts Honors Program, at William Paterson University.

Bill Wolak: Your latest novel is entitled If Anyone Asks, Say I Died From the Heartbreaking Blues. Tell me a little about the blues in the title and how it relates to the rest of the book.

Philip Cioffari: The “blues” in the title refers both to the tradition of blues music, which is to say the expression of sadness, sorrow, and longing rendered via music and voice into a beautifully crafted, aesthetically pleasing form; and also the personal blues all of us, in one way another, feel at various points in our lives. In my book, specifically, it is the blues of adolescence that accompanies the search for self, love, and the sense of belonging to a world we don’t yet understand. The actual title comes from an African-American folktale about two mythical figures, Betty and Dupree, and the love that pulls them apart.

BW: In this novel, music is evoked on just about every page, beginning with that enticing jukebox on the cover. Why did you highlight music throughout the text?

PC: Music, in this case the popular music of the 1950s and 60s, is an integral part of the characters’ lives. In a way, it is the soundtrack of their lives, spinning out from radios, jukeboxes, record players. And since my novel is basically a love story, music becomes inextricably involved with the search for love. This was the time that Rock n’ Roll (Rhythm n’ Blues) was new. For the first time, teenagers had a music that was exclusively their own. A music full of throbbing energy and passion, a parallel to the energy and longing bubbling up inside of them. Every song was a celebration. I hope that the use of music in the book helps capture some of that youthful passion and longing.

BW: The entire novel takes place in a single day. Is there a reason why you compressed the action into such a brief amount of time?

PC: I like to use a compressed time period for my novels. I find it raises the tension and urgency of the story. After all, in real life the clock is always ticking, time is running out—which, of course, adds urgency and poignancy to each moment we live. It intensifies the “drama” of our lives. So, too, in fiction: the dramatic element is heightened. I also like the idea of going deep moment by moment—that is, exploring each step of my characters’ journeys, including the silences, the moments when nothing seems to be happening, but something is happening, always. At the risk of sounding too esoteric, I like to convey the moments between moments. I like to pay attention to those small, almost unnoticeable feelings and half-thoughts. This is easier to do when the scope of the novel is shortened.

BW: You’ve been writing short stories, novels, and plays since the 1970s. Do you tend to base your fictional characters on people you have known or have heard about, or are they more what one might term imaginative constructions–composites of several people?

PC: I don’t have one person in mind as the basis for a character. They seem to evolve out of my imagination, and, yes, I suppose if I were to break them down they’d most often turn out to be composites of people I’ve known. I don’t usually do that, though. I prefer to experience them as imagined beings.

BW: One of your characters is described as “the unofficial investigator of the mysteries of the universe.” Is this what you set out to explore in your fiction, to examine aspects of the universe that remain mysterious?

PC: The mysteries within ourselves and within the world at large are a primary fascination of mine. I’m intrigued by the investigative process, the search for truth of one kind or another. The more elusive the truth the more compelling to me.

BW: In the short story “Turns” from A History of Things Lost Or Broken, the female dance instructor says, “. . . the turn transports us gracefully from one state of being to another.” Do you tend to concentrate on the sometimes banal and sometimes unexpected “turns” or choices characters make in your short stories?

PC: Moving from one state, one feeling or one condition to another is an imposition life places upon us. We’re continually in motion. We must learn to make those moves and the more gracefully we can make them, the better.

BW: As in your novel The Bronx Kill, the most typical Cioffarian landscape is set in the Bronx, in the neighborhoods where you grew up. Why do you think you return so often to the streets, the els, the backalleys, the projects, and the mud-flats of your youth when you write?

PC: I don’t really know. What I do know is those landscapes haunt my imagination. They’re alive for me in a burning way. I never seem to tire of them. In my latest novel, for example, the dance clubs of the Bronx in 1960 had particular qualities that reinforced the cultural norms, that in some ways predetermined the social interaction between boys and girls, the difficulties and awkwardness that kept them apart. I tried to capture those environments in order to provide a context for my characters’ actions.

BW: Parts of Catholic Boys take place in a a bomb shelter that resembles a Borgesian labyrinth. Is that bomb shelter sprawling underneath a vast apartment complex something you actually experienced as a child?

PC: There was one similar to it in the housing project where I lived. It was a fall-out shelter with long, barren hallways—what we, as kids, named “The Hundred Halls.” There were an endless number of carriage rooms and basement rooms that were dark and shadowy and mysterious. For the novel I embellished the design somewhat.

BW: On the other hand, both of your novels Jesusville and Dark Road, Dead End take place outside of New York. How did you go about researching the settings for these two novels? Or did the stories develop out of the settings?

PC: A strong sense of place is something I strive for in all my writing. In fact, I would go so far as to say it’s what gets my stories off the ground. I can’t really write without having a firm physical and emotional grasp of the setting. That’s why I always write about places I’ve been to, where I’ve had the opportunity to feel what it’s like being there: the quality of light, for instance, as it changes throughout the day; the colors; the sounds; what the air smells like when you inhale. I also believe that where something happens affects the way a character behaves. In fact, often it seems my stories develop from a sense of place. In the case of Jesusville, I came across an article about a defunct religious theme park somewhere in Connecticut. I was fascinated by the photos and the descriptions of Biblical scenes that had fallen prey to decomposition and neglect. About the same time, I came upon another article about a retreat for troubled priests hidden away in the New Mexico desert. Quite suddenly a landscape formed in my mind that contained both places. Soon after, the characters began to take shape, one by one. I had to find a reason why they would all end up there, and once they arrived, how they would be affected by the stark beauty and isolation. From my visits to New Mexico, I had come away with a distinct sense of its spiritual qualities, something I rarely experienced elsewhere. I wanted to find a way to infuse my story with that spirituality, hence my characters’ search for a rare hallucinogenic plant that would allow them to see God. Dark Road, Dead End grew out of my many visits to the southern tip of the Everglades. I found that area to be captivating. I liked the end-of-the-road feel of the place. The towns and settlements literally dead-ended against swamp. There was no escape. Once there, you had to find a way to survive, or die. Life was lived on the edge, a raw one at that. The physical world of marsh and water and forest intrudes upon every aspect of existence. I talked to whomever of the townsfolk who would talk to me. I wanted to hear about their lives, the way they saw the world, and because the history of that area had been so dominated by smuggling of one sort or another, it became a natural setting for my environmental concerns—in this case, the smuggling of illegal exotic animal species into the United States.

BW: How and when did you first conceive of Love in the Age of Dion, the work that propelled you from fiction to theater and finally to film?

PC: It began as a title for a short story: “Love in the Age of Dion.” A spin-off perhaps from the Garcia Marquez title, Love in the Time of Cholera, though I can’t be sure, of course. Ideas generate from so many sources. In any case, there it was: a title in search of a story. For several years it rattled around in my head, yielding nothing more. I was a professor at a state university in New Jersey, teaching creative writing, publishing stories in commercial and literary magazines. This was 1998. That fall, the story came to me: Frankie, a man whose second marriage has just fallen apart, returns after twenty years to his old neighborhood in the Bronx, in search of his first love, hoping to re-capture what he thinks of as the best days of his life. The neighborhood he knew has changed, but his old hangout, a working man’s bar where he drank his first beer, has survived: same bartender, same songs on the jukebox, memories for the taking. He spends the evening there with Eddie, his best buddy from the old days–who never left the neighborhood–and a woman who happens to be in the bar that particular evening.

BW: After you had the basic plot and a setting, what was happening in your writing at that particular time to change the trajectory of the piece?

PC: During this time I was studying playwriting at HB, an acting studio in Greenwich Village. I’d begun the class as an exercise, a way to develop my ear for dialogue. An editor at Doubleday had read a novel of mine and made the observation that I told the story mostly through narrative, using dialogue sparsely. Till then I’d never thought much about it. Narrative came naturally to me, so I’d indulged myself. But her comment made me realize I was insecure about writing dialogue; unconsciously, I’d been avoiding it.

BW: So studying playwriting became a strategy to hone the dialogues in your fiction?

PC: Yes, but I debated the issue a while. Why was dialogue so important? Jim Harrison, after all, had written Legends of the Fall without a single line of dialogue. On the other hand, so many best sellers relied heavily upon it, and one couldn’t deny it greatly enlivened the pace and feel of a scene, to say nothing of its use as a tool for revealing character. Writing plays seemed a likely way to get over my unease.

BW: Did you ever publish the short story “Love in the Age of Dion?”

PC: For some reason, I never sent the story out. Instead, over that winter break, I wrote it as a one-act play. Shortly thereafter, it was produced at the American Theatre of Actors in New York City and, though I was reasonably satisfied with the outcome, I thought it ended abruptly. My lead character, Frankie, storms out of the bar once he learns his old buddy has no intention of taking the trip down memory lane with him. I wondered what would happen if Frankie didn’t walk out, if he stayed to confront the past as Eddie remembered it, unglamorized, thick with pain.

BW: What was your connection to the American Theatre of Actors?

PC: With the American Theatre of Actors, I simply submitted three one-act plays. I had heard they were open to producing plays from new playwrights. They called and offered to do two of them–one of them was the one-act version of “Love in the Age of Dion.”

BW: How did you modify the original ending of the one-act version?

PC: By writing a second act. Basically, I made Frankie hang around and deal with the situation. That, in turn, led him to a place he would never have reached if he’d simply run off. The final result was a full-length version that had four characters, one setting. Ideal, from a producing point of view.

BW: Where was the original two-act version of the play first produced?

PC: It was first produced at the Belmont Italian American Playhouse, an equity theatre in the Bronx, where it played weekends—Thursday through Sunday—from October, 1999 until June, 2000, an almost nine-month run.

BW: Before they produced your play, did you have any involvement with the Belmont Italian American Playhouse?

PC: My only prior involvement with the Belmont Playhouse was that I’d been attending their plays for a number of years. I was impressed with the quality of their work–the actors were superior, as was the director Dante Albertie. For a small theatre they managed to get many favorable reviews from the NY Times, the NY Daily News, and the NY Post. I knew they would do a good job with my play and that I would be honored to be produced there.

BW: Why do you think the Belmont Italian American Playhouse was so enthusiastic about producing your play?

PC: In many ways it was a perfect play for them. It was set in that neighborhood, it made reference to Dion, the local hero, it had the urban flavor and sensibility that they liked. I thought, if they don’t like it, I’m in big trouble.

BW: After its run at the Belmont Italian American Playhouse, did you have any possibilities to move the play to an Off-Broadway theater?

PC: At that point, several producers took interest, with plans to move it to Off-Broadway the next year, but 9/11 intervened and, in the wake of that disaster, the plans were scrapped. However, I was fortunate enough to have an enthusiastic and devoted cast who helped me stage a backer’s audition at the Chelsea Playhouse in Manhattan. Again, there was interest. Drea De Matteo did a staged reading of it before she was lured off to L.A. to star in the sequel to the TV series, “Friends.” Ed Asner liked it enough to offer to do a staged reading of it–as the bartender–the next time he was in New York. There were murmurings again from producers, and again nothing came of it.

BW: Is this about the time that you made the transition into directing?

PC: The play lay fallow for several years. During that time I’d been gaining experience as a director. I’d been taking classes in directing and, as luck would have it, a position as director opened at my university; I began directing in our black box theatre. I favored contemporary comedies, especially the work of Christopher Durang, whose plays were so different in tone and mood from the kind of plays I was writing. From directing students, I went to directing Off-Off Broadway where I was both writing and directing. There’s a school of thought in theatre circles that says playwrights should not direct their own work, but I longed to do both. I didn’t want to be angry at someone else for “ruining” my work, or for misunderstanding my intentions. If the production turned out badly, I wanted no one to blame but myself.

BW: At that point in your career, you had been writing and publishing fiction for a long time. What prompted you to begin the daunting task of transforming the play into a film?

PC: At this time my fiction was at a standstill. I wouldn’t call it writer’s block so much as writer’s plateau; I couldn’t reach higher ground. It was the fall of 2004 by then, and as the end of the year approached, I grew quite despondent. New Year’s Eve I was hiking with my friend Bill, a TV producer, when he suggested I make a movie. “You’ve got the script,” he said. “You’ve got some great actors, and I can hook you up with a Director of Photography.” As a bonus, he offered to serve as producer. He’d made this same suggestion several times over the years, but I’d always found the prospect overwhelming. I didn’t think I could pull it off. There was so much I didn’t know. I’d never been to film school, never made a short, never even been on a shoot. It seemed too much of an effort, too great a chance for failure.

BW: So what intrigued you that New Year’s afternoon about Bill’s proposal?

PC: Maybe it was the cold, grey bleakness of the day, or the prospect of the long winter months ahead without any writing ideas on the horizon. Or maybe it was simply the rut I was in. Time to try something new. The next day I began writing the screenplay. In addition to the four characters in the play, I added Carmel, a friend of the sole female character. She was mentioned in the play but never appeared. For the film version I knew I needed some comic relief, as well as someone who could offer an objective view of the conflicts between the main characters. Carmel was the answer. I also had to “open up” the play. I wanted to get the characters out of the bar so I added outdoor scenes: on the street, in a playground, at the beach. In the play the events of the past are simply narrated, but in the film they could be dramatized fully and more effectively as flashbacks. And I forced myself to rely more heavily on visual images to replace some of the dialogue.

BW: One of your most courageous acts in the making of the film has to be that you invested your own savings in the project. Could you explain how you managed to finance the film?

PC: I knew the only way I was going to have complete control over the creative content was if I financed it myself. So I exhausted my savings account. Which isn’t as bad as it sounds. We kept expenses to a minimum. Most people worked for nothing or for deferred compensation–so if the movie gets distribution, I’ll owe them. Those who were paid worked for reduced wages because they liked or had some interest in the script, or needed experience.

BW: What was the first, crucial step that got this project off the ground?

PC: In the months before the shoot, there was a never-ending list of things that had to be done. The first of them was scouting locations. In early February I began looking for a bar. Finding one, one that looked “right,” was crucial, since two-thirds of the script was set there. Without one, there could be no movie. The script is set in the Bronx, so I began there. Always a fan of authenticity, a Bronx bar for a Bronx movie seemed to me the right way to go. But this would be no easy task. Because the story is set in two time periods—1966 and 1992—I needed a place that hadn’t changed much over time. I also wanted one with character, with a lot of dark wood, old-fashioned mirrors, ceiling fans, an old jukebox, maybe even sawdust on the floors. And I needed one with a dance floor, and one large enough to accommodate my cast and crew—about twenty people—and all our equipment. Over a period of four months I must have looked at more than a hundred bars. I began at the Bronx/Yonkers line and worked my way down upper Broadway. I went to City Island, Arthur Avenue, Pelham Bay, Morris Park. Most of the bars I looked at had at least one disqualifying attribute: it was too small, or lacked character, or had been modernized. With those I liked, money was the problem. Given my budget, no one was willing to close down for the two weeks I needed. They’d been spoiled by shows like “Law & Order” which came in for a day or two and paid thousands of dollars. A few places offered to let me shoot during their off-hours, between 4 and 8 a.m., an impossible situation for my actors, who had day jobs.

BW: How did you end up selecting the bar?

PC: Time was running out. I wanted to begin shooting in early June, and it was already May. At that point I had only one possibility. The Shannon. A dive bar under the El in Pelham Bay. The owner, a short-tempered 84 year old Irishman, was willing to close down for ten days so he could attend an Irish music festival in the Catskills. The price, $4,500, was something I was willing to pay, but the place had problems. For one thing it was small, tiny, and for another thing, we’d have to deal with the noise of the #6 train rumbling by every ten minutes or so. But worst of all, every inch of wall space and every shelf behind the bar was filled with Irish memorabilia—leprechauns, photos of the River Shannon, four-leaf clovers, you name it. My story was set in an Italian neighborhood. Which meant we’d have to spend at least a day dismantling the place and substituting Italian-American artifacts, and at least another day restoring the original décor, hoping the curmudgeonly owner wouldn’t notice upon his return. So with less than two weeks before our shoot date, I intensified my search. I looked in Brooklyn, Jersey, even Manhattan, which I knew would be prohibitive cost-wise—all to no avail. In a last-ditch effort I went back to the Bronx, to a section near Mosholu Parkway where I hadn’t yet looked. I checked every bar along Bainbridge Avenue and was about to give up. There was one bar left, Gorman’s, on the corner of 204th and Webster. I was so discouraged by that time I was resigning myself to dealing with the leprechauns. But I pushed myself on. The place was, if not perfect, the best I’d seen. Old mirrors with dark wood trim and blue, fluted lights, an old-fashioned black and white tiled floor, ceiling fans. A throwback to an earlier time, a genuine relic. And luck was on my side. The bar was closed for the summer, he informed me. He kept it open September to May for the exclusive use of Fordham University students. Within minutes we reached an agreement. Three thousand dollars for three weeks of shooting. He was happy for the unanticipated income; I had a place to shoot my movie. And not a moment too soon—a scant ten days before we were to begin shooting.

BW: What was the next step after you had nailed down the bar?

PC: During the four months of my pub quest I was doing a hundred other things as well, not the least of which was putting together my cast and crew. My guiding principle was to find the most natural, ordinary-people types—the guy or girl you’d find sitting next to you at an outer borough bar. As with writing, I believe authenticity is the ultimate goal. For my two male leads, I decided to use the actors who starred in the play—Jerry Ferris and Tod Engle. Though not well known, they were excellent at their craft, and they played well together. For my female lead I went to Christina Romanello, an actress I’d seen in a play a few years back. One of my habits was to keep on file the headshots and resumes of actors I’d seen perform, and whose talent I admired. For the role of Carol, the long-lost first love, who would appear only in flashback, I wanted a certain look. I couldn’t describe that look, but knew I would know it when I saw it. I placed an ad in Backstage, the newspaper for aspiring actors, and received more than four hundred responses. Sorting through the head shots of these women, one more beautiful than the next, I came upon the photo of Marta Milans. I knew immediately she was the one I was looking for. Her audition bore that out. She was so moving in the portrayal of a woman with a broken heart, able to bring herself to tears in such a deeply felt and believable way, that she left those of us watching her speechless. For the supporting female role, my comic relief addition, I placed an ad on Mandy. com, an Indie filmmaker’s website. The woman I finally chose, Bridget Trama, unsure of the role at first, eventually came to exceed my expectations with her performance. And last but not least I found my bartender through a referral. Jack Ryland was the most experienced of my actors, a veteran of Broadway. Though hesitant at first—he wasn’t keen on making the trip from Manhattan to the Bronx—he finally signed on. And again, not a moment too soon: three days before we began shooting.

BW: What was your rehearsal schedule like?

PC: We had time only for five or six rehearsals. We worked on rendering the material in a truthful way, and we did some basic blocking—most of which had to be re-done when we were on set.

BW: Where did you find the rest of the film’s crew?

PC: During the rehearsal process, Victor and I were also busy putting together a crew. He was able to bring in hard-working and dedicated film students to fill the roles of gaffer, grip, and script supervisor. Again, I used Mandy.com to find a Sound person, an Assistant Director, and an Art Director. I trusted my instincts—did they have experience? Could I work with them? Count on them? Would they accept the wage I could offer? My brother-in-law doubled as line producer and production manager, and my sister volunteered to make sure we had enough to eat and drink on set.

BW: How long did it take to shoot the film?

PC: We shot the movie in seventeen days in June. I was free for the summer, but most of the cast had day jobs, so we filmed nights and weekends. The first ten days we spent in the bar, beginning about 6 p.m. The first few hours were consumed with setting the lights and getting the actors made up; shooting began about nine o’clock. Each day I re-wrote the scenes for that night’s shoot, mostly cutting dialogue. I had to keep reminding myself of the sparse language of film.

BW: Were there any unexpected problems during the filming?

PC: For each night of the shoot, Murphy’s Law applied: what can go wrong, will go wrong. For one thing, we hadn’t counted on the loudness of the buses that bullied their way down the avenue every fifteen minutes or so, or the salsa music that blasted from the open windows across the street. Nor did we anticipate the thumping noises that emanated from the apartment above the bar—the superintendent’s children having their innocent fun running or jumping or bouncing balls or beating their dolls to death against the floorboards. So many sounds we pay little attention to in ordinary life, but when you’re filming and need absolute quiet the smallest sounds assume the proportions of an explosion. Naturally, I pleaded with the super to control his children. As for the buses and salsa, we simply had to work around them.

BW: Your nights of filming in the bar sound exasperating. How did the outdoor scenes go?

PC: The outdoor shoots were more enjoyable, though I’d been dreading having to deal with so many more forces out of our control. After so many nights in the bar, it was a relief to get out into the bright sunshine. And the problems we encountered were largely of my own making. The Mayor’s Office of Film Development never returned my calls, and I was too busy to chase after them. Hence, no permits. When we shot in the subway, we kept changing trains every ten minutes, whenever we suspected the conductor was on to us. This was three days before the London subway bombings, after which security became so tight on NYC transit lines we would surely have been arrested, our camera confiscated, and we would have been subject to heavy fines.

BW: So all the outdoor shoots went well?

PC: No, we weren’t as fortunate on our playground shoot. We began early Sunday morning, thinking we could get in and out before anyone noticed. There was only one five-minute scene we needed to shoot. Things went well for most of the morning. We had maybe twenty or thirty seconds of script to shoot when the Parks Department showed up in the person of a brawny, no-nonsense woman who told us to pack up immediately and clear out, or else be subject to arrest. We packed up immediately and cleared out. But we had to finish the scene. While the cast cooled off in our rented air-conditioned van, Victor and I drove frantically around the Bronx in search of another playground that would match the one we were forced to leave. We found one some twenty blocks south, in a poor neighborhood where dealers were plying their trade and junkies were shooting up near the swings. Within minutes we’d attracted a crowd of several hundred who lined up along the fence to watch. The part of the scene we were shooting involved a fight between a white man and a black man. The tension building in the crowd was palpable; a few of the actors were getting nervous, but I insisted we stick it out. We finished the scene and moved on. Our last day of shooting—and our biggest challenge—took place at the beach. It was a scorching hot day and we had several emotionally intense scenes to film. When we had scouted the location, the place was quiet, ideal for filming, but not so on the day of the shoot. The beach, it turned out, was on a direct flight path to La Guardia airport a few miles across Long Island Sound. Jets came roaring over us every sixty seconds. We had to constantly stop the actors—sometimes in mid-sentence—and hold until the plane passed over, then begin shooting again. What amazes me to this day is how flawless the actors were, able to stop and start without losing focus, without dropping a line, without losing the emotion of the moment.

BW: How would you compare the process of writing fiction to the process of filmmaking?

PC: There’s a tremendous difference in the way you fix mistakes. Movie problems are also much more varied. If you make a mistake in fiction, if you don’t like the way a sentence turns out, you simply erase it and do it again. If you make a mistake filming, it costs a considerable amount of time–hence, money–to re-shoot, so you’re continually under pressure to get it right as quickly as possible. In fiction, your sole concern is with words and making them serve your creative imagination. In film, your creative impulses are held hostage by so many annoying and frustrating technical and practical concerns. Case in point: many scenes in the script were set at night. Well, night lighting was too prohibitive in cost and time, so those scenes had to be converted to daytime. In fiction, you want rain, you put in rain. In low-budget Indie film making, forget about it. Who had time to wait for a rainy day, or the equipment to get it lit properly? And always, every minute of every shoot, the curse of Murphy’s Law is hanging over your head. Yet I consider it one of my personal triumphs that I learned to make whatever adjustments were necessary, that I learned to convert obstacles into advantages, that we always found a way.

BW: How would you describe the kind of pressure you were under while you were shooting?

PC: For those seventeen days I lived in a zombie haze. Part of that was physical exhaustion. I wasn’t sleeping much, nor sleeping well. I had no appetite. After our night shoots which wrapped up between one and two a.m., I would drive the cast into Manhattan, making my last drop-off at close to four in the morning. Then I drove back to my apartment in Jersey. When I fell asleep, my dreams were anxiety-ridden—about camera angles and dialogue changes, and lighting and sound problems for which I could find no solution. And part of that zombie haze came from mental and emotional overload. Too many details, large and small, to remember, but all of them necessary—from making certain the actors were staying truthful on camera to wondering if the dinner would arrive on time; and though my small crew was the most devoted and helpful a director could hope for, I was the one, finally, responsible for getting the movie made, for making sure it was the best movie we were capable of. I don’t want this to sound like a complaint. I wanted to be in control, that’s why I wanted to both write and direct. And the control freak part of my personality reveled in this.

BW: Do you have any regrets about what happened during the shooting of the film?

PC: I can’t say I had as much fun on the set as I might have liked; I was too busy for that, but I have to say when we finished shooting on that last day, the sense of peace and accomplishment was like nothing I’d ever experienced.

BW: Of course, shooting the film is only half the battle. What was your experience of mixing the film like?

PC: The technical process of taking what we’d shot and turning it into a movie began soon after we finished shooting. A film is made on the cutting room floor, the cliché goes. I remember what Jack Haigis, my editor, said the night I dropped off the twenty-two hours of videotape we’d shot. ‘The first thing we have to do is see if we even have a movie here.” What he meant, of course, was whether the collection of individual scenes was sufficient to make a complete and integrated piece, with a beginning, middle and end.

BW: How did you find your film editor?

PC: Jack was one of the more than two hundred and fifty editors who responded to my ad on Mandy: Indie filmmaker seeks experienced editor. Low pay. Sorting through the resumes, I recognized his name immediately. He’d edited two of my favorite urban dramas: Straight Out of Brooklyn, and Graves End. When I sent him the script and he agreed to take me on, I was overjoyed. By day he worked at a full-fledged editing studio in Manhattan, and by night he worked out of his apartment in Westchester. Each morning I’d go through the raw footage, select my preferred takes, and bring them to him in the evening. We worked this way for several months. I got to see the film take shape in bits and pieces until finally one night he declared, “We have a movie,” and we went out for pizza and beer to celebrate.

BW: What remained after you had mixed a rough cut of the film?

PC: Jack added the music.

BW: Was the film ready for viewing at this point?

PC: Yes, so I arranged to screen it at my university before a small audience of colleagues and students. What had appeared to be minor imperfections on a TV-sized monitor loomed large and egregious on the big screen. There were radical, jarring discrepancies in lighting and color from scene to scene. Some scenes were under-lit, some over-lit. The light in the bar was too bright, more appropriate for a luncheonette than what was supposed to be a gritty beer and shot night spot. In short, it looked awful. I was thoroughly embarrassed, overwhelmingly depressed. It seemed that eight months of effort had ended in failure.

BW: What did you do?

PC: I brought it back to my editor. “Not to worry,” Jack said. “That’s what post-production labs are for.”Several months and several thousand dollars later the film finally looked presentable. The lab was able to make the lighting and color look natural and consistent. They were even able to add shadow to the bar scenes to give them a moodier and more appropriate feel. At last I had a ninety-minute version of the film that I could watch without cringing, a version which didn’t distract from the skillful work of the actors and the story I wanted to tell.

BW: What is your goal for the film now?

PC: The ultimate goal of this process is, of course, to find distribution, preferably theatrical or TV distribution first, then distribution in the home DVD market. The route to this, if you’re not well-connected in the film industry, is via film festivals. The process is roughly akin to publishing in literary magazines before a big house decides to take you on.

BW: Have you entered it in any film festivals?

PC: I chose not to submit to the top-tier festivals like Sundance and Tribeca, which receive three to four thousand entries per year and where one is competing against movies with big stars and multi-million dollar budgets. I opted for the smaller festivals, the truly independent festivals which receive a mere one to two thousand entries, most without big name actors. I was fortunate that in the first festival I entered, the Long Island International Film Expo, my film won the Best Feature Film award. What a thrill to sit in a dark theatre and watch an audience of strangers react to your work. Love in the Age of Dion went onto win a Best Actor award and a nomination for Best Director at the Hoboken International Film Festival, a nomination for Best Film at the Staten Island Film Festival, a Best Director Award from the NY Independent Film & Video Festival, and was an official selection at the Rhode Island International Film Festival, and the New Filmmakers New York series at Anthology Film Archives.

BW: One of your early experiences in the film industry was as a movie reviewer for Penthouse Magazine. How did you come by that job and what did it involve?

PC: Penthouse had bought several of my short stories and basically liked my writing. They knew of my interest in movies and asked if I’d like to review films for them. Of course, I accepted. Being a movie reviewer seemed like a dream job. In reality, I became quickly disenchanted. For one thing, going to the movies became a job and an obligation rather than something freely chosen for pleasure. I had to see whatever was out at the time, usually two or three movies a week, many of them mainstream Hollywood movies which held no interest for me. My tastes ran to more obscure independent or European movies that often were not well known enough for the magazine to want to print a review. But I will say I liked being able to attend advance screenings which were held in plush screening rooms in Manhattan. They made sure we reviewers had popcorn and soda, whatever we needed to help us enjoy the experience.

BW: Over the years, which filmmakers would you say have exerted the most influence on you?

PC: I’ve always been drawn to the gritty, urban realism 50s dramas like Paddy Chayefsky’s “Marty” or the Hecht-Lancaster productions of “The Bachelor Party,” “Sweet Smell of Success,” and “A Hatful of Rain.” I loved the American New Wave films of the 60s and 70s, especially Bob Rafaelson’s movies, “Five Easy Pieces,” and “King of Marvin Gardens.” And, of course, I’m a great admirer of the Italian and French New Wave, especially the work of Da Sica, Visconti, Antonioni, Fellini, and Truffaut, to name a few.

BW: Do you have a favorite film?

PC: Hard to pick a single film, but certainly in the top tier I’d put “The Deer Hunter,” “The Bicycle Thief,” and the aforementioned 50s film, “The Bachelor Party.”

BW: Over the years, you have maintained a regimented writing discipline. Could you describe your daily writing routine?

PC: I write usually 3-6 hours in the morning, seven days a week.

BW: Which short story writers, novelists, playwrights, and poets do you think have had the greatest influence on your writing?

PC: Certainly Graham Greene, Tennessee Williams, William Faulkner, Paddy Chayefsky, Carson McCullers and Flannery O’Connor. And newer writers like Kem Nunn and Newton Thornburg and David Rabe.

BW: Who were your most inspiring teachers?

PC: Certainly Anatole Broyard (fiction) and Claude Underwood (Acting) at the New School. M. L. Rosenthal (Poetry) at NYU, and William Packard (Playwriting) at HB Studio.

Philip Cioffari’s Website:

www.philipcioffari.com

Works by Philip Cioffari available on Amazon.com:

If Anyone Asks, Say I Died From the Heartbreaking Blues

The Bronx Kill

Dark Road, Dead End

Jesusville

Catholic Boys

A History of Things Lost Or Broken

Bill Wolak is a poet, collage artist, and photographer who lives in New Jersey and has just published his eighteenth book of poetry entitled All the Wind’s Unfinished Kisses with Ekstasis Editions. He has published interviews with the following poets, writers, and artists: Anita Nair (India), John Digby (United Kingdom), Dileep Jhaveri (India), Gueorgui Konstantinov (Bulgaria), Naoshi Koriyama (Japan), Sultan Catto (United States), Ilmar Lehtpere (Estonia), Jeton Kelmendi (Kosovo), Yesim Agaoglu (Turkey), Mahmood Karimi Hakak (United States), Srinivas Reddy (United States), Chryssa Nikolakis (Greece), Philip Cioffari (United States), Yongshin Cho (Korea), Manolis (Emmanuel Aligizakis) (Canada), Jami Proctor Xu (United States), Stanley H. Barkan (United States), Annelisa Addolorato (Italy), and William Heyen (United States).