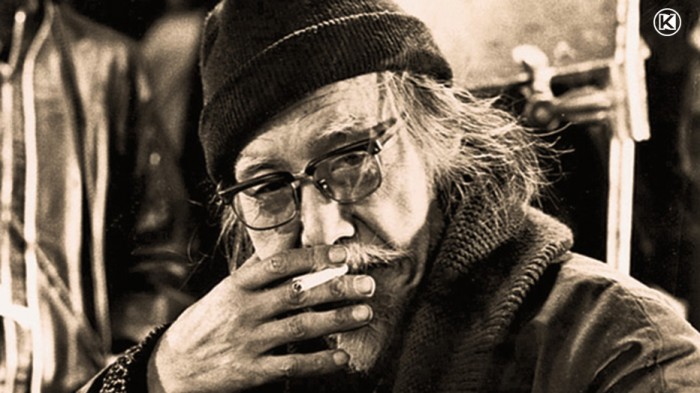

Still the Master – Seijun Suzuki Legendary Filmmaker

by Chris Casey

Tokyo Drifter, 1966

On May 24, 2014, Suzuki Seijun, one of my most favorite filmmakers turned 91. Under typical circumstances, I would have created a status post about Suzuki’s birthday for my Facebook page. However, since the passing of my father, I have found myself to be physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually busy with first one thing then twenty others. Therefore, I have to confess, I simply forgot about Suzuki-sensei’s 91st birthday.

Interestingly enough, though, yesterday was the first time in many, many moons I was actually able to sit down to watch some movies and guess what films I chose to watch? Two classics from none other than birthday boy, Suzuki Seijun, himself! Perhaps, subconsciously I remembered it was his birthday—but, then again, perhaps not. All I know is that there are a fistful of films I call my “comfort movies” (these are films that I can, and do, put on and enjoy anytime, anywhere—but, most especially when I am feeling out of sorts). And among my comfort movies are the Suzuki masterpieces I watched, yesterday: TOKYO NAGAREMONO (TOKYO DRIFTER) and KOROSHI NO RAKUIN (BRANDED TO KILL).

They just don’t make ’em like Suzuki Seijun anymore.

SUZUKI SEIJUN

Undeniably, the most well-known practitioner of Nikkatsu Action eiga (at least in the West) is maverick director Suzuki Seijun. His work for Nikkatsu Studios ranks as some of the most intriguing and visually stunning cinema ever produced, in any country or within any genre. Over the past ten years, an endless number of film journalists, critics, and fans, have written miles of well-deserved rabid reviews, and elegant essays regarding this colorful director’s life and his brilliant work. In most of these articles, Suzuki is likened to “outlaw” directors such as Samuel Fuller, Robert Aldrich, and Jean-Luc Godard. Although, he no doubt shares much with these celebrated auetuers, he is also very much unlike them. With a few exceptions, these other directors worked outside of restricting studio systems. Seijun, on the other hand, boldly made his own artistic statements within the confines of such systems, making him a completely unique, and paradoxical, rebel of conformity.

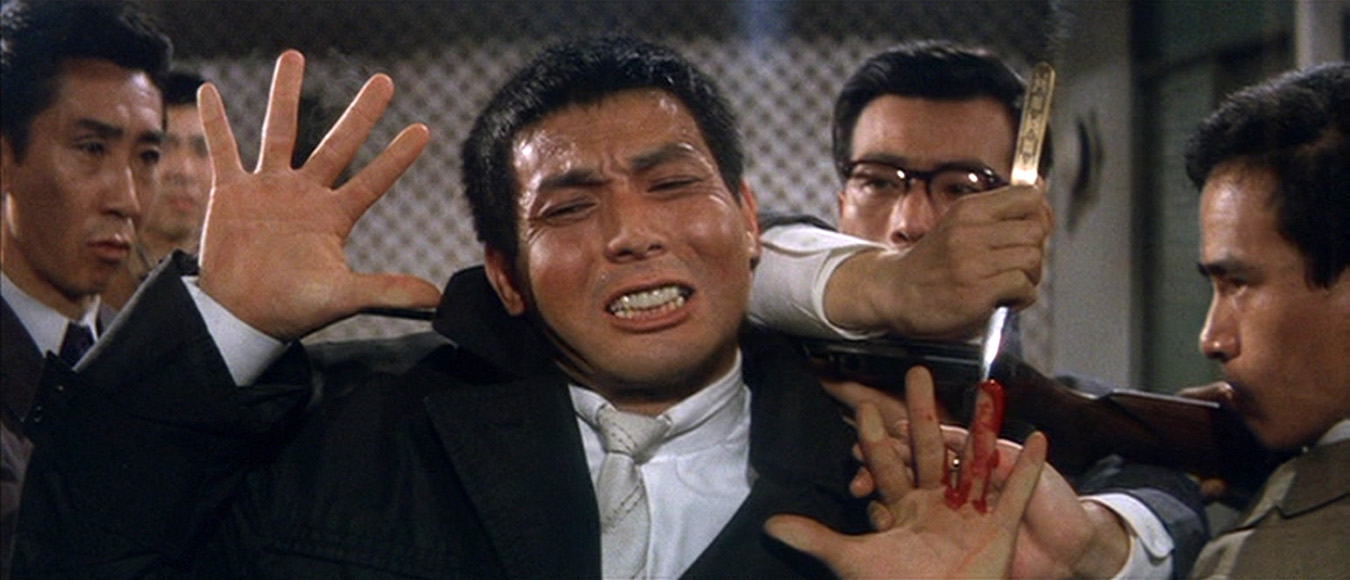

Branded to Kill, 1967

Typically, Suzuki Seijun films are hyperbolic, intense, overtly melodramatic, flamboyant, and frequently just barely within the lines of controlled chaos. However, at the same time, they are subtle, sensual, and highly artistic in execution (though Suzuki, himself, would firmly deny it!). The medium to which Suzuki’s work is most closely related would be the traditional Kabuki style of theatre. Suzuki-sensei’s surrealistic use of color to denote various emotional aspects of the scene, his utilization of sound, his stage-like framing, and the acting style of the performers, often reflect Kabuki–as tempered through an anarchic, cinematic eye.

Suzuki’s works have been frequently referred to as radical (in both the good and bad sense of the word!); and radical they most definitely are. Yet the wild, rebellious nature inherent in his films could be interpreted as a logical extension, or reflection, of the world in which Suzuki grew up.

Born Suzuki Seitaro in May of 1923, Suzuki (and thus his film work) is a product of the tumultuous Taisho period. This period of Japanese history (including the years between 1912 and 1926) was a volatile time of cultural upheavals and political revolutions. These were chaotic–yet, picturesque—days of newly imported, translated, and assimilated, philosophies, literature, and entertainment forms (including silent films) mixing with traditional Japanese ways and viewpoints. This cultural wildness seems to have left an indelible mark on Suzuki’s psyche.

After completing a course at Tokyo Trade School, in 1941, Suzuki attempted to enter the College of the Ministry of Agriculture; but, he failed the entrance exam because he was weak in physics and chemistry. For a brief time he did basically nothing (with the exception of watching numerous films), until he somehow managed to end up in a college at Hirosaki. However, his days as a student were soon cut short.

Suzuki was drafted into service during World War II in 1943. While serving as a Private, second class, he was shipwrecked twice. Sometime after these experiences he was promoted to the rank of Second Lieutenant with the Meterological Corps in the South Pacific.

In 1946, after the War, Suzuki returned to Japan and his studies at Hirosaki. He finished his courses there and attempted to enter the prestigious Tokyo University; but, he failed to win a place there. Trying a new direction altogether, the young film buff, Suzuki, decided to heed the advice of a friend, and enrolled in the Film Department of Kamakura Academy.

In 1948 Suzuki was accepted as a salaried employee at the Shochiku Film Company’s Ofuna Studio. While with Shochiku, he worked mainly as an assistant director. He worked a great deal and learned a lot; however, he was not making very good money. After six years, he decided to transfer to Nikkatsu purely for–he claims–financial reasons.

Youth of the Beast, 1963

At Nikkatsu, Suzuki again worked chiefly as an assistant, though better paid, to many of the studio’s best directors. After proving himself to be a very efficient second unit man, and a very capable scriptwriter, he was finally given the chance to direct features of his own. Still using his real name, Suzuki Seitaro, he began his illustrious career as a full-fledged director in 1956 with a minor-league pop music film. Suzuki quickly became a skilled master of studio-dictated, production line features; however, with each new film assignment he seemed to try a little harder to entertain the audience in a new way and make tired ideas seem fresh.

With the 1958 crime film, “Ankokugai no Bijo” (“Beauty of the Underworld”), Suzuki Seitaro became (and would remain) Suzuki Seijun. Yet, the “Seijun Style” would not truly come to exist until 1963 and the release of three perfect examples of Sensei’s art, “Tantei Jimusho 2-3: Kutabare Akutodomo” (“Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards!”), “Yaju no Seishun” (“Youth of the Beast”), and “Kanto Mushuku” (“Kanto Wanderer”).

From 1963-1967, Suzuki Seijun created some of the most amazing pieces of cinema ever screened. Always trying to top himself in an effort to “keep the audience from getting bored,” each successive project seemed to push a little closer in exceeding the limitations of genre, budget, and expectations.

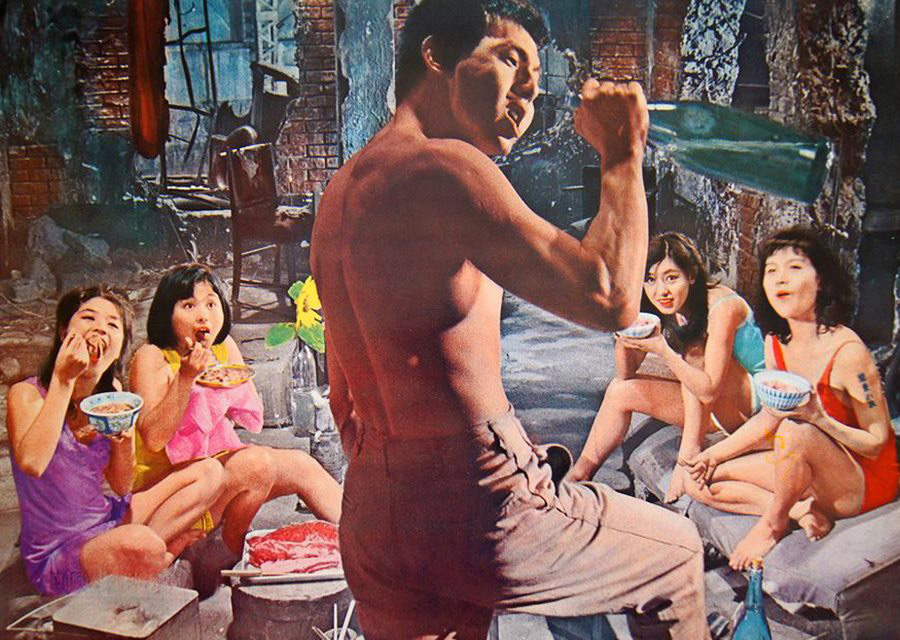

Gate of Flesh, 1964

In 1967, Nikkatsu was having some major money problems. Kyusaku Hori, the company president at the time, decided (for who knows what reasons) to make Suzuki the scapegoat for the entire company’s financial woes and fired him for making “incomprehensible” movies that made no money. Kyusaku particularly hated “Koroshi no Rakuin” (“Branded to Kill”), a film that is now regarded as Suzuki’s masterpiece worldwide.

Ignoring all protests from fellow Nikkatsu workers, friends, and student groups, Hori stuck to his decision to dismiss Seijun. Feeling rightfully cheated, Suzuki took an unprecedented step and sued Nikkatsu for wrongful dismissal, a case which the director won three and a half years later. Though he won in the courts, Suzuki was effectively blacklisted by all of the major studios for nearly ten years.

Filling these lean years by directing a few commercials and publishing books of essays, Suzuki constantly sought ways to continue his filmmaking career. In 1980 he joined with independent producer Genjiro Arato and released a new film, “Zigeunerweisen“. The film was a great success with critics, and did well financially despite the fact that it was not allowed to be distributed through normal circuits. In fact, Suzuki and Genjiro distributed the film themselves, exhibiting it via a specially built mobile theatre!

Since that time, Suzuki has directed two more independent works, “Kagero-za” (“mirage Theatre”) and “Yumeji“, as well as one film, “Capone oi ni Naku” (“Capone’s Flood of Tears”), for his former employers, Shochiku. His Nikkatsu films began getting noticed in the West sometime in the mid to late 1980’s with festivals, from Italy to Canada, successfully screening many of his classics. In the ’90s, with the advent of more niche-oriented home video (DVD) and the World Wide Web, Suzuki’s cult of admirers has continued to expand (and deservedly so).

Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards!, 1963

Recommended Suzuki Films:

BRANDED TO KILL (Koroshi no Rakuin, 1967)

YOUTH OF THE BEAST (Yaju no Seishun, 1963)

TOKYO DRIFTER (Tokyo Nagaremono, 1966)

KANTO WANDERER (Kanto Mushuku, 1963)

STORY OF A PROSTITUTE (Shunpuden, 1965)

GATE OF FLESH (Nikutai no Mon, 1964)

UNDERWORLD BEAUTY (Ankokugai no Bijo, 1958)

TATTOOED LIFE (Irezumi Ichidai, 1965)

DETECTIVE BUREAU 2-3: GO TO HELL, BASTARDS! (Tantei Jimusho 2-3: Kutabare Akuto-domo, 1963)

THE FLOWER AND THE ANGRY WAVES (Hana to Doto, 1964)

All titles, with the exception of THE FLOWER AND ANGRY WAVES, have had U.S. DVD releases.

BIO

Chris Casey is a musician, writer, film buff, occasional actor, and nagaremono currently residing in Stillwater, Oklahoma, USA. Chris digs: Japanese action cinema of the 1950’s and 1960’s, Spy flicks and TV shows of the 1960’s, Westerns (Spaghetti and American); Film Noir; Hard-Boiled Pulp Fiction; Mods, R&B; Soul, Beat Music, Jazz, Ska, Reggae, Punk, Instrumental Surf Rock, Dashiell Hammett, Carroll John Daly, Raymond Chandler, Mishima Yukio, and much more.

Chris Casey is a musician, writer, film buff, occasional actor, and nagaremono currently residing in Stillwater, Oklahoma, USA. Chris digs: Japanese action cinema of the 1950’s and 1960’s, Spy flicks and TV shows of the 1960’s, Westerns (Spaghetti and American); Film Noir; Hard-Boiled Pulp Fiction; Mods, R&B; Soul, Beat Music, Jazz, Ska, Reggae, Punk, Instrumental Surf Rock, Dashiell Hammett, Carroll John Daly, Raymond Chandler, Mishima Yukio, and much more.