An Analysis

By Robert Boucheron

As a baby, the patient had golden curls, a skin complexion of white and rose, and chubby limbs, all of which prompted strangers to say, “What a little angel!” By way of proof, he brought an album to the psychotherapeutic suite. Photographs showed a cherubic little boy in a romper. Under one picture was written “His new shoes. Adorable!” Another showed a pair of gossamer wings affixed to his back as a costume. For confidentiality, and because the analysis depends in part on the nickname, I will call the patient “Angel.”

At the time we met, Angel was in his twenties, sensibly groomed, wearing street clothes. His manner was earnest, ready to confide. His body was well-developed in bone structure and muscle mass. His facial features were regular. He said he ate a balanced diet and exercised three times a week at a gymnasium. Now and then he posed as a photographic model in advertisements for clothing and consumer products.

“You’ve probably seen me in a newspaper insert for a department store sale,” he said. “I have the right combination of chiseled masculinity and bland vacancy,” he said. “On the street people stare without knowing why. A moment later they forget about me.”

In a large city, hundreds of people pass in the course of a day. It is impossible to remember one seen for an instant on the street, or for the duration of a ride on public transit. And freelance gigs are common. Was the patient unduly sensitive? Did he expect too much from a casual encounter?

In possession of a superb body, a good address, and many creature comforts, Angel said he suffered from a lack of purpose, a sense of cluelessness. This mental state was so strong, he said, “I struggle to get up in the morning, drift through the day on automatic pilot, and go to bed with a feeling I accomplished nothing.” Angel was employed full-time, I should point out, in the business office of a well-known manufacturer of medical supplies and products for the care of infants.

From the age of fifteen, Angel experienced an inner compulsion, a need to tell others what was on his mind. “I had this urge to express myself. It was like I had an important message, only I didn’t know what the message was, or who it was for.”

In the way of adolescent boys, he was silent and sullen, afraid to blab. When not shooting baskets or throwing a football, he began to write poems, scraps of dialogue, and short stories. He dared not show these pieces of writing to anyone. Even the mention of them caused his face to burn red from embarrassment.

“They were awful, exactly what you would expect, imitations of what I read in English class and what I heard on television. I threw them away.”

Angel did well in high school. He attended college, where he studied the liberal arts, and graduated at a favorable time to enter the labor market. Life proceeded smoothly. Within the metropolitan area, he found a job and an apartment, made friends, and as noted, picked up modeling assignments.

Unmarried, Angel had dated women since his teens. Lately he had been seeing a young woman I will call “Mary.” From his description, Mary was amiable and unremarkable, much like him. He showed me her photo on his pocket phone: an attractive brunette with nothing on her mind.

Mary and Angel met for dinner once a week, watched movies together, and engaged in bedroom frolics. The neurosis, then, had nothing to do with repressed or deviant sexuality, the subject of so many cases. Meanwhile, in the placid pond of Angel’s life, the urge to write seethed below the surface.

“Now and then, I grabbed a notebook and started to scribble. I never knew what was going to come out, only that I had to put words on paper. It was an itch I had to scratch. I heard voices in my head, like characters in a play. Plot lines, conflicts, descriptions of places. Moods and sudden turns. This might sound crazy, but writing stuff down was my way of coping.”

“Nothing sounds crazy,” I said. “Feel free to say whatever comes to mind. Ramble and rant, blather and blurt. An analyst listens and takes it all in. Did you know, by the way, that ‘angel’ means ‘messenger’ in Greek?”

“No. So what?”

“In the interest of putting our time to its best use, allow me to ask a question. Do you still feel compelled to write?”

“Yes. Now I type on a laptop.”

“Do you favor poetry or prose?”

“Mostly I stick to stories.”

“Creative writing is a harmless hobby. Where is the problem?”

“After all these years, I still don’t know what my message is. What am I trying to say? And who needs to read it?”

“Has Mary read your work?”

“No. She isn’t into contemporary fiction.”

“Have you talked to her about writing?”

“A little.”

“And what is her response?”

“She says, ‘I’m here for you.’”

“Does she encourage you?”

“She says, ‘If that’s what you really want to do, maybe I can help.’”

“Do you love her?”

This challenge elicited a degree of squirming, and at last an affirmative.

The onset of symptoms at puberty implied that Angel’s “message” was simply the need to find a receptive partner, or in biological terms, to seek a mate. The frustration he experienced in writing stories indicated a misdirection of psychic energy. The analysis suggested a course of action.

“Write a love letter to Mary,” I said, “not a literary exercise, but a sincere declaration.”

Angel did so. Mary’s response was encouraging. It led him to propose marriage. Without hesitation, she accepted. The next day, Angel reported this to me by text and attached a photo of the two, all smiles.

“You know that mysterious urge to write?” the message said. “It went away.”

A follow-up session was unnecessary.

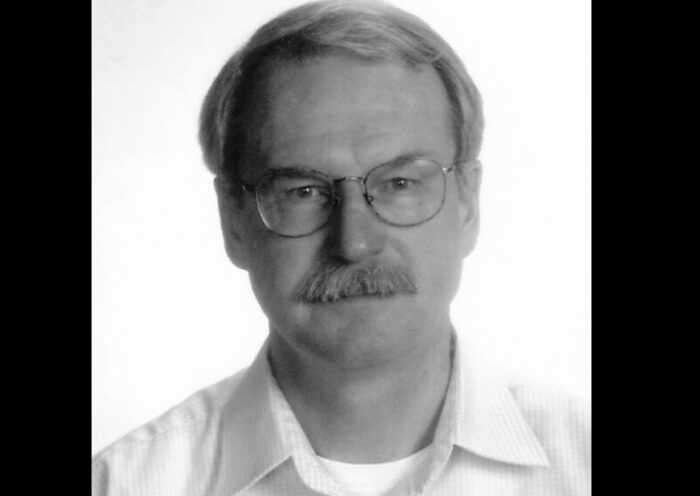

BIO

Robert Boucheron is an architect in Charlottesville, Virginia. His short stories and essays appear in Bellingham Review, Christian Science Monitor, Fiction International, Louisville Review, New Haven Review, and Saturday Evening Post. He is the editor of Rivanna Review. His blog is at robertboucheron.com