Cry Havoc and Let Slip the Dogs of War:

Man’s Best Friend on the WWII Battlefield

By Paul Garson

All photos & illustrations from the Author’s Collection

Capt. David Vogel, of the 102nd Engineers, trains in war games with dog Rex in a photo taken in 1935.

Capt. David Vogel, of the 102nd Engineers, trains in war games with dog Rex in a photo taken in 1935.

When Shakespeare had Marc Antony, after Caesar’s assassination, lament … Cry havoc and let slip the dogs of war… the phrase appearing in the Bard’s 1601 play Julius Caesar… he was not referring literally to dogs. Although huge canines were used in Roman warfare, the phrase was originally a signal used by English military commanders of the Middle Ages to signal their soldiers to begin the usual pillage and chaos accompanying engagements on the battlefields.

The Bark Heard Round the World

While the wolf became man’s companion 12,000 years ago, it would be 4,000 years before the historical record indicates they were first trained as wardogs, oddly enough in Stone Age Tibet. As far back as 800 B.C. illustrations of mastiff like dogs were trotting alongside King Tut’s chariot as seen in his tomb art. Apparently large fighting dogs were also popular with Kryos, then King of Persia who had then harnessed and sent to the frontlines of battle.

The effectiveness of the dog as weapon eventually took hold worldwide. Some 30,000 of the mastiff type dogs became a staple of Kublai Khan’s 13th century all-conquering army. In the following centuries, wardogs have appeared in times of conflict taking on a variety of roles from message carriers to sentries to first aid providers to living bombs and occasionally as supplemental rations.

Eventually brought into Europe, the Romans took hold of the concept breeding smaller dogs for herding and guard dogs, larger ones as weapons of war, the latter equipped with spiked collars and armor while some carried containers of open flame on their backs to create panic among the enemy’s warhorses. One of the first “hero dogs” recorded was named Sorter, the only survivor of 50 wardogs that were the first to meet a surprise attack by Athenian soldiers during the Corinthian War (395-87 B.C.). Sorter ran to the citadel arousing the sleeping garrison who threw back the attacking force. In appreciation the dog was awarded a silver collar with an inscription, “To Sorter, defender and savior of Corinth.”

Columbus brought 20 tracking dogs with him to the New World and the Spanish Conquistadors used attack dogs in their destruction of the Aztec empire. By 1500 dogs were serving as frontier guards, catching errant cattle in England and tracking runaway slaves in America where Benjamin Franklin in 1755 described the best way to use dogs “against the Indians.” By the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the French Army had organized complete camps to care for their canine soldiers. In the early 1900s when battling the French and Spanish in colonial Morocco, the Rif natives dressed dogs in their clothes to attract gunfire and thus reveal the enemy’s positions.

The very first recorded dog show took place in Belgium on May 28, 1847 near Brussels. Then in 1880 a Belgian breeder, Edmond Moecheron, became famous throughout Europe by giving sideshow-like demonstrations of his specially trained “police-dogs” which set the whole concept in motion. This breed of Belgian Shepherd, similar in appearance to the Rottweiler, came into official police use in 1899.

Wardog as Standardized Weapon

Moving forward to the first of the World Wars, the British embarked as it were on a head start program just prior to the outbreak of hostilities when they began organizing a War Dog Training Center under the leadership of a Lt. Col. E. H. Richardson. They however had taken the cue from the Red Cross which first promoted canines for ambulance duties on the Western Front. While England thought it a jolly good idea, its French allies found the idea unacceptable and quickly banned their ambulance attendant use shortly after the war began. In the autumn of 1914, Richardson, undaunted, then focused on equipping his charges for sentry and patrol duties. After finding the breed particularly adaptable to the requirements, Airedales were his main choice but the Catch-22 was that he had to requisition the dogs from their source in France. He managed to acquire a few four-footed French recruits that apparently learned English very quickly. The training went well and the British found support in their efforts when their Belgian allies were receptive to the idea, Richardson then supplying them with several of his graduates. Some also went to Britain’s WWI Russian allies who equipped the dogs with medical supplies and set them lose to find the wounded lost in the desolate landscape of Manchuria.

The Belgian military had previous experience with dogs of war, having employed a special indigenous breed, the now extinct Matin–Belge, apparently a very sturdy Mastiff variation that often pulled heavy machine guns and ammunition carts.

Meanwhile the English were looking for more uses for their dogs, so Lt. Col. Richardson provided two Airedales, aptly named Wolf and Prince, to his comrades at the Royal Artillery, 56th Brigade, 11th Division and received glowing reports as to their performance which accelerated further efforts to develop more dogs as messengers in the field.

A training school was subsequently established in France, the main kennels located in Etaples initially under the direction of a Maj. Waly, then by 1917 the operation came under the control of the Royal Signal Corp. Each human handler was acquainted with three dog trainees and vice-versa. As the British were particularly fond of their dogs and provided for those in need, many were found available from various Dog Homes in Bristol, Liverpool, Birmingham, and Manchester. Due to an ever increasing demand, strays from all over the UK were rounded up by the local constabulary, then as the need continued to mount, additional “volunteers” were requested from the general public. The appeal was well-answered by those felt they were unable to adequately feed their pets as a result of war rationing. Soon it was raining “dogs and dogs.”

The German Shepherd aka Alsatian aka Wolfdog was first developed in 1899 by Capt. Max von Stephanitz who through careful breeding produced an ideal service dog under the motto “utility and intelligence.” Their jaws exerted 238 psi of pressure, second only to the Rottweiler. Eventually introduced into the military by the Prussians, the Reichswehr had 6000 dogs trained for battlefront duty during WWI.

Germany also trained their dogs to carry and deliver medical supplies and sometimes a bit of schnapps. At times they wore the symbol of the German Red Cross (Rotes Kreuz), a collar identifying them as a “comfort dog” or Sanitätshunde in the service of the German military. While they were trained to ignore corpses, the dogs were trained to retrieve from the wounded soldier his Bringsel, a decorative cord that was an element of the Prussian uniform. After bringing the cord to a medic, the dog would lead his human team mates to the wounded soldier. As the injured were treated, the dog would provide comfort therefore the name “comfort dogs.”

Back in America, with its isolationist policy looking askance at entering a European war, its canine contribution amounted to some 400 sled dogs provided for use by the French military, the war raging on three years prior to U.S. involvement. However, one French dog, a Highland Terrier, adopted by an American infantryman saved many WWI doughboys, his acute hearing warning of artillery attacks as well as his success in delivering critical messages under fire. Named Rags, and besides surviving many wounds, he was also the first dog to parachute when his owner found it necessary to bail out of an observation balloon. Perhaps the most decorated and most famous WWI canine was a bulldog named Stubby whose intelligence and bravery saved many American soldiers to the point he was presented to three Presidents-Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge.

By war’s end in 1918, some 30,000 dogs had served with the Allies and Central Powers and had brought aid to the fallen, acted as couriers, first-aiders, guards and early warning sentinels. Over 3,000 were KIA.

Angels Disguised as Devil Dogs: America’s Elite Canines

“At Ease” – New Recruits at WWII U.S. Army Training Center

Several breeds are represented including a Great Dane, German Shepherd, Doberman, Airedale, Collie, Labrador and good American mutts. While not seen in this photo, one of the first wardogs was the poodle. One such four-legged French hero was named Moustache who though wounded rescued the French flag at the famous battle at Austerlitz on December 2, 1805.

* * *

Playing K-9 Catch-up

While the U.S. the military had neglected wardog training during the first war, they began to catch up prior to the following war, in part due to the campaigning efforts of a dog breeder named Arlene Erlanger who, anticipating the need, formed a group called Dogs for Defense. Celebrities of the day added their vocal support of the program including movie stars Rudy Valle and Mary Pickford who in fact gave their personal dogs in the hopes of inspiring the American public to follow suit. Eventually the U.S. military, who named their war dog project the K-9 Program, began experimenting with some 30 breeds before focusing mostly on German Shepherds and Dobermans, the selectees then trained for sentry, patrol, messenger, tracking, and mine-detection duties. Some dogs even joined U.S. paratroopers and British SAS parachuting with them into enemy territory.

All such dogs were held in high regard for their loyalty, intelligence and courage under fire, often laying down their lives for their humans. They were especially valued in the Pacific Theatre where the Marines faced stealthy assault by skilled Japanese infiltrators. The canine warriors often slept in the foxholes with their handlers. The dogs exercised exceptional hearing, up to 35,000 hertz per second as compared to a human’s maximum of 20,000 as well as the ability to close-off their inner ear and micro-focus on a particular sound. Acute audio skills were complemented by a sense of smell some 100 times more acute than a human and capable of following a scent several days after originally made and as far away as 250 yards. As a result, these war dogs served as “early warning systems” often sounding the life-saving alarm while their intense loyalty and fearsome aggressiveness often threw them into direct hand to paw combat.

Training Takes a Twist

A more than strange story comes out of the effort to train war dogs for Pacific duties, i.e. battling the Japanese. A plan was hatched to teach dogs to identify Japanese people. Some 25 Japanese-American soldiers were asked to volunteer for a secret mission. They found themselves off the coast of Mississippi on Cat Island which apparently had the climate of the Pacific islands plus plenty of alligators. According to veterans who took part, they spent four hours a day training the dogs, the rest fishing, playing guitars and drinking plenty of beer since the island’s water was sulfurous.

Training consisted of feeding the dogs meat and firing a gun at the same time for several months. Then a period when the Japanese –Americans were ordered to whip the dogs until they bled which resulted in the dogs being very eager to bite them anytime they saw them. It wasn’t popular with the dogs or the soldiers. As it turns out the plan didn’t pan out, the dogs didn’t differentiate between races, and most dogs were too civilianized to take well to the training. When a demonstration for the brass didn’t go well, the military pulled the plug on the program in July 1944 but not before 400 dogs went through the Cat Island experiment. A more traditional war dog training program was then initiated.

Leathernecks with Collars

During WWII, there were also rigorous programs organized at the Marine Corps War Dog Training School at Camp Lejuene, NC. As a result, several Dog Platoons were formed then sent with their handlers to take part in many of the amphibious landings on Japanese island strongholds including Guam, Bougainville, Guadalcanal, Iwo Jimo, the Philippines and Okinawa. On Guam alone, the dogs took part in over 550 scouting patrols during which 40% saw encounters with the enemy detected by the canines. Many of the dogs and their handlers seeing action in the Pacific campaign paid the ultimate price but in the process saved hundreds of American lives as well as contributed to the destruction and capture of hundreds of the enemy. Many of the Pacific islands had their own wardog cemeteries. On Guam alone, one such burial place held 25 K-9 soldiers.

The dogs, trained to withstand the sound of gunfire and explosions, were also taught to remain silent when they detected danger so as not to alert the enemy. A technique was developed that saw the handler, when sleeping at night in a foxhole, would lie with one hand, palm up, against the throat of his dog. Although trained not to bark or even growl when detecting an enemy soldier creeping toward the foxhole in the cover of darkness, the dog’s throat would emit a vibration that would be felt by his handler and thus awaken him in time to thwart the attack. Obviously both dog and man were very much in tune with each other, deep bonds that often saw sacrifice from both. In one instance, a Marine K-9 familiar with the effects of grenades, saw one land nearby a group of leathernecks, grabbed it its jaws and ran clear of the men, but not in time to drop the grenade.

Pool Training

Special training installations could be used both for water and fire simulations. Here a dog is being gently introduced to a water training site used by the 508th Parachute Infantry, 82nd Airborne. Notations on the back of photo identify the dog as “King” and the soldier as “Pittman” while the installation is located in Frankfurt, Germany, the time frame a few months after war’s end.

The photo and caption appeared in the August 1944 issue of the American Legion Magazine. The sleek, almost elegant yet fear-inspiring Doberman-Pinscher was prized by American troops for their skills and bravery, especially in the Pacific battlefield and where, as a result of their short fur, the animals weren’t as affected by the heat and humidity as other dogs. Originally the Marines inherited many German Shepherds from the Army, but later gained many Doberman’s thanks to the efforts of the Doberman Pinscher Club of America. Some estimates indicate 75% of the dogs in Pacific service were Dobermans.

Successful Landing – February 1943

In a Signal Corp photo snapped somewhere in England, a dog named “Salvo” is shown planting his feet on the ground to resist the pull of his open parachute while waiting to be released from his harness by his U.S. Arm Air Corps fellow soldiers.

Salvo appears to have some Jack Russell in him while the two aircraft in the background appear to be an American ‘spotter’ and a British open cockpit trainer, each bearing the emblems of the U.S. Army Air Corps and British Royal Airforce.

Semper Fi – South Pacific – August 1943

A Marine “devil dog” named Andy joins his two legged comrades, PFC Robert E. Lansley of Syracuse, NY and Lt. Clyde A. Henderson of Brecksville, OH. The trio was photographed somewhere on Bougainville, the island the scene of savage fighting during the campaign that lasted from November1, 1943 until August 21, 1945 as U.S., New Zealand and Australian troops battled the deeply entrenched Japanese holding the island.

The term “devil dog” was actually the name given to U.S. Marines by their WWI German enemy, while G.I.s and Marines considered their canine comrades “angels.” In this case Andy and his handlers were “on point” during a patrol on the look-out for snipers and ambushes. Andy would trot ahead and “indicate” if danger lurked nearby. At one point Andy indicated something was not right with two banyan trees flanking both sides of a trail. The Marines then noticed the trees had been camouflaged as machinegun nests and destroyed them before they could unleash their lethal cross-fire.

Many dogs serving in the Pacific developed illness and contracted diseases caused by the climate as well as insects. Often the dogs had to survive on a diet of C-rations and many with thick coats suffered from temperatures reaching well over 100 degrees. Heartworms and kidney diseases were common afflictions not to mention shrapnel and gunshot wounds for which they were cared for by medics alongside their human comrades.

Hail Caesar – Two Bullets Couldn’t Stop Him

While he may not have received a Purple Heart, a Marine-trained K-9 Corps Shepherd named “Caesar” earned the gratitude of the leatherneck with whom he served for saving his life and taking two bullets in the process. During the battle on Bougainville, Caesar, a member of the 1st Marine Dog Platoon, was on patrol with his two handlers Prvt. Rufus Mayo of Montgomery, AL and Prvt. John Kleeman of Philadelphia, PA, both members of M Company, 3rd Raider Battalion. In the dense jungle their walkie-talkies became useless so Caesar filled the gap as the main source of communications from the soldiers’ position at a strategic roadblock and the command post in the rear. Caesar made nine round trips under fire and later prevented a Japanese infiltrator from dropping a grenade into the marine’s foxhole, but in turn was shot twice. He recovered and lived on, but with a bullet lodged near his heart.

Meanwhile on the European Front, American K-9 soldiers were performing above and beyond the call of duty as sentry dogs, ammo carriers, messengers, mine detectors, search and rescue, even in combat roles and parachuting with Airborne troops. A Shepherd/Husky/Collie mix named Chips landed on Sicily with Patton’s Seventh Army during the operation ironically called Operation Husky. Detecting a camouflaged pillbox, the dog raced forward diving into the bunker and routed the Italian machinegun team forcing four to surrender. Chips was awarded a Purple Heart and the Distinguished Service Star, the first and only dog in the history of the United States to do so. His act of bravery under fire spurred further recruitment and use of wardogs. However when he nipped Gen. Eisenhower’s hand, he was relegated back to sentry duty, but eventually was “pardoned” and took part in the D-Day invasion.

The story even turned up as part of a comic book that gave the backstory about Chips, the dog volunteered by Gail and Nancy Wren from Pleasantville, NY. The story describes him as a “mutt” and both he and his handler, the latter named Rowell, as being clumsy and a lot of trouble according to their sergeant. One of the panels even shows Chips nipping Eisenhower, followed by Chip and his handler in a landing craft under fire during the landings on Sicily and also his routing of the machinegun nest.

Corporal Butch on Home Front Patrol – Spy Catcher – 1944

The Westinghouse press release photo dated August 10, 1944, appeared with the following caption:

“Good work, pard,” says Sgt. Denkel J. White to canine Corp. Butch after the war-plant police dog had discovered a strange man rowing a boat in the Delaware River near the Westinghouse Merchant Marine plant at Lester, Pa. “even if he didn’t turn out to be a saboteur.” Corp. Butch helps guard the waterfront and the plant where turbines to drive America’s merchant marine fleet are made. The police say Corp. Butch, part Shepherd, part Chow, is “nearly human” in intelligence. Each night he picks one of them to accompany on the beat. He won’t fraternize with anybody who doesn’t wear a uniform. He has his own floor fan, identification and police badges, and hospitalization fund (5 cents a week from each policeman.)

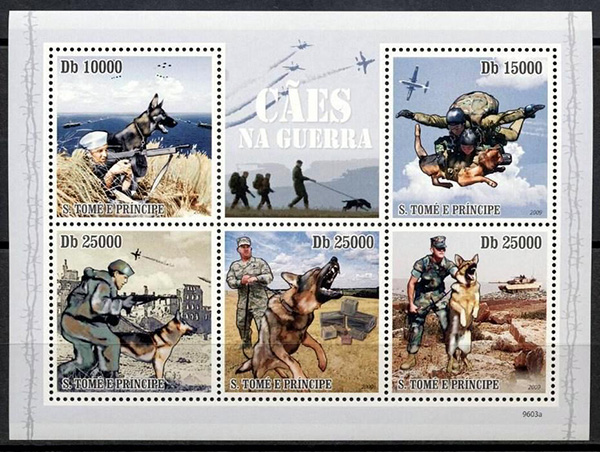

Caes Na Guerra – War Dogs – 2009 S Postal Issue by Sao Tome e Principe

The postage honoring wardogs was printed by the Democratic Republic of Sao Tome and Principe, two volcanic islands straddling the equator located off the central eastern coast of Africa and comprising the continent’s smallest country (964 sq. miles), but they are big on stamps, a source of international revenue.

The Fate of Man’s Best Foxhole Friend

Prior to 2000 and new legislation allowing “discharged” wardogs to be adopted by civilians, service dogs were “euthanized” aka killed. An estimated 10,000 dogs were trained for WWII service. Of the 559 dogs still in the field at the end of WWII, 540 were “repatriated” to civilian lives. However of the estimated 4900 Vietnam wardog veterans still overseas, only some 200 made it back to the states. Thanks to new legislation, today most wardogs return to good stateside homes with applications for adoption far exceeding the number of dogs available.

BIO

Paul Garson lives and writes in Los Angeles, his articles regularly appearing in a variety of national and international periodicals. A graduate of the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars and USC Media Program, he has taught university composition and writing courses and served as staff Editor at several motorsport consumer magazines as well as penned two produced screenplays. Many of his features include his own photography, while his current book publications relate to his “photo-archeological” efforts relating to the history of WWII in Europe, through rare original photos collected from more than 20 countries. Links to the books can be found on Amazon.com. More info at www.paulgarsonproductions.com or via paulgarson@aol.com

Paul Garson lives and writes in Los Angeles, his articles regularly appearing in a variety of national and international periodicals. A graduate of the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars and USC Media Program, he has taught university composition and writing courses and served as staff Editor at several motorsport consumer magazines as well as penned two produced screenplays. Many of his features include his own photography, while his current book publications relate to his “photo-archeological” efforts relating to the history of WWII in Europe, through rare original photos collected from more than 20 countries. Links to the books can be found on Amazon.com. More info at www.paulgarsonproductions.com or via paulgarson@aol.com