Grace Street

By Frederick Pollack

The most significant photo

of my childhood isn’t of me

but a man three stories down,

alone, galoshed, earflapped,

woolen (long before parkas

even for soldiers), bent against the wind

(there was always wind), responding

tactically to ice ahead. It could

be noon but is almost as dark

as the brick apartment buildings

in their long lifetime

of soot. An age and neighborhood

of small deals, nominal

top tax rate 94%, the B-36s

of the Strategic Air Command

protecting us. (I could sell you

reasonably the damp grey

dry-rotted windowsill above

the radiator, over which

I could almost see.) All I know

for sure about the walker

is that he’s dead. So I can

hope that his small deal

that day went through – that

the girl, lawyer, shop steward

accepted the line

he was rehearsing. And

coopt him for other purposes, as

he was already.

The Loom

What if art had been different? During the

rappel à l’ordre

of the 1920s, everyone shifts

to tapestries. (What manifests ordre

more than a tapestry?) Not just a few

luxury experiments – the norm:

more weavers, brought in from the provinces,

in Paris than lithographers

(someone always profits). Leger’s robots,

Braque’s tremulous (head-wound) yellow-greens,

fuzzy. A creeping if not creepy

nostalgia for pre-artillery

stone walls sets in; Maurras and his cane-

wielding monarchists approve;

Dada withers, Surrealism

never takes off. Everywhere

texture, pastels in the light

of calla-lily lamps, covert vertical

frottage. Bonnard’s twelve-meter offering

at the Hôtel de Ville. Even

the poor nail up their linsey-woolsey

reproductions of “Verdun.” Soon, portraits

of various Leaders assume

this presence all over Europe,

wall-posters vaguely déclassé. In an

Italian film (the “White Telephone” school

absorbs neorealism), a girl

of the people, being kept by

an aristocrat, pulls

a tapestry from his wall and

wraps herself in it,

lying on a patch of parquet; her dark

eyes flash as she cries,

“My whole family could sleep under this!” …

You can see her, can’t you.

One of the Names

I came voluntarily.

It was nicer than I’d hoped.

They were pleased I’d given up

without a fuss my tent beneath the overpass,

brought nothing but a clipping,

didn’t fight (like some I knew)

for every plastic bag. Accepted

delousing, tests, shots,

without screaming. And the jumpsuit.

Answered their questions, said I had no skills

(which gratified them after days and weeks

of shamans, lathe operators,

superannuated sex workers, agents

of or against the secret masters, ex-

executives, Jesus).

Didn’t ask for a drink.

There but for the grace of God,

I’d like to think they thought.

On the benches in the big room,

the shadows of four windowless towers

(more going up) crossed

my comrades, who, if they talked at all,

said one way or another

It won’t hurt. One yelled we’d be killed

immediately, or our spoiled bodies

flushed in a year or two

down some hole; he was dragged away. Few

speculated when we’d be awakened.

I thought of nothing else.

Didn’t imagine a fresh start,

cures, kindness. Only

the power keeping on and on,

concrete remaining whole, letting us out

finally on a former

sea floor. What I’d really like

is just eight minutes as the sun goes nova …

the sun will need me.

Thousand Aves Told

With the demise of monasticism, there is now no place where one can

professionally execrate the world.

After the Revolution, we take seriously

Cioran’s lament. With the joyous, self-congratulatory

élan that comes with the demise

of money, we build in forests and waste places

negative structures: not pseudo-ancient

or aggressively austere.

The chapels at their heart

lack altars, but the chairs are hard

and widely spaced, the quiet quieter.

With our usual warmth, we ensure

that those who wish to enter

have not attempted suicide too often,

or killed, and probably won’t. Offer

counseling, leave a number

they can call if they want. (In all this

we show a consideration

not extended to religion.)

Left alone, they tend to adopt

a partial code of silence, banning

the loudest and most defensive. Make their beds,

grow their food. Through

the windows in the common room

or, often, from narrow hallways

they stare at cherished birds and trees and

sometimes, on the horizon,

us building. Nights they see a face

they wounded, or their own. They consider

the dark beneath the earth. Whisper

curses shaped over years and carefully

inscrutable. Gods and things like gods

exude like sweat or winter breath; despite

the care they have for each other,

to some the place feels always hot or cold.

And they fight and break up fights, and eat in dimness.

Co-ed. Flirtation frowned upon.

But sometimes two wind up in the same cot.

With the understanding that, tomorrow,

they will leave without goodbyes,

fasten each other’s pack, descend

to the trailhead and the nearest town

with its windmills, brass band,

and equivocating, indispensable banners.

Personal Items

Eventually they return

my passport, jacket, tie,

phone, and hat. One declaims

haltingly their sorrow

for any inconvenience; I sign

a form saying I have no complaints.

Become almost tearful,

seeing again my stickered, scuffed,

beductaped leather suitcase.

It will look as suspect and as quaint as I

(I know – I’ve followed the world

on television) among

those twirling, weightless things

that people pull along

like aphids dragging pupae. These

unfurl, I’ve heard, into well-appointed

shelters for those homeless who can afford them.

Prepare hot meals on the run.

Equipped with stirrups, can be ridden

or (for all I know) flown.

Are in touch with the great mainframe

and commiserate with their owners

on the horrors of travel. My smartphone,

likewise, will seem no longer

smart. No more will I – must reinvent

my look as “aged but resolute.”

Nor, I must say, do the officials,

whose uniforms were redesigned

(and not to their advantage) during my stay.

They hesitate, handing back

my suitcase. Will they subject it

to yet more dogs, decryption, x-rays, profiling?

“Would you like to check … ” asks one

with unauthorized compassion.

I smile as if I scarcely care.

After so long, I know what’s in there.

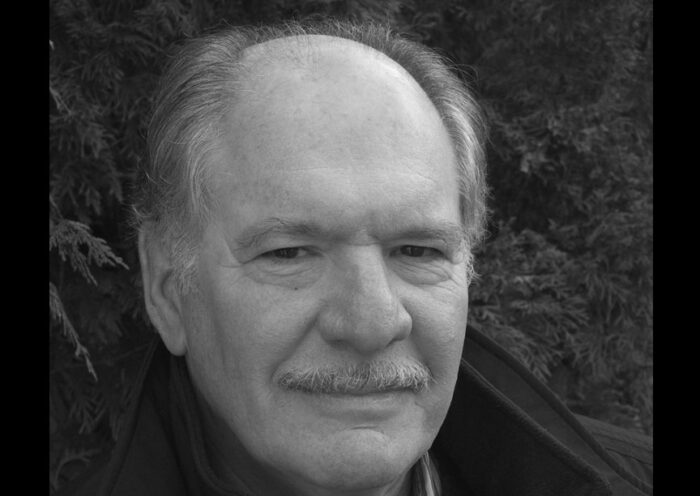

BIO

Frederick Pollack is the author of two book-length narrative poems: THE ADVENTURE and HAPPINESS, both from Story Line Press; the former to be reissued by Red Hen Press. Also two collections of shorter poems: A POVERTY OF WORDS, (Prolific Press, 2015) and LANDSCAPE WITH MUTANT (Smokestack Books, UK, 2018). Pollack has appeared in Salmagundi, Poetry Salzburg Review, The Fish Anthology (Ireland), Magma (UK), Bateau, Fulcrum, Chiron Review, Chicago Quarterly Review, etc. Online, poems have appeared in Big Bridge, Hamilton Stone Review, BlazeVox, The New Hampshire Review, Mudlark, Rat’s Ass Review, Faircloth Review, Triggerfish, etc.