The Embers

by Daniel Mueller

At potlucks you never failed to evoke the flesh and blood of the living Christ. Once all were seated at card tables in the church basement before plates heaped with Beth Ann Constable’s meatloaf, Ruth Goetzman’s chicken casserole, Helen Wolfe’s deviled ham puffs, Margo Humphrey’s German stew, and my then-wife Lorna’s short ribs, seared in batches on the stove and braised in the oven in tomato sauce seasoned with Tabasco, with arms outstretched and palms to the ceiling you asked the Lord to bless our food and reminded us that it was, in sacramental terms, no different from the morsels of bread and thimbles of grape juice distributed during communion. A skeptic at best, I said my “Amen” with the others and tried to ignore any pangs of conscience, but never forgetting that in Dante’s Inferno the lowest circle of Hell was reserved for hypocrites.

Dinners at your home, on the other hand, were served without a word of grace. You and Bev were close in age to Lorna and me, your daughters Holly and Jill close in age to our sons Leo and Vance, and in addition to the canoe trips down the Saint Croix River our families took together each autumn to admire the colors, every six weeks you would join us for supper at our house or we’d join you at yours. Still, as much as our families enjoyed each other’s company, I’d come to dread the moment when, our wives and children having retired to their respective domains, you would say, “May I have a word with you, Bruce?”

“Sure, Myron,” I’d say. Then we’d descend the stairs to one or the other of our partially modeled basements, to one or the other of our paneled offices, mine displaying in a locked mahogany gun rack the Browning 30-30 deer rifle and Remington 12 gauge pheasant gun that had followed me from childhood, though I’d lost all interest in hunting after the boys were born, yours displaying a framed diploma from Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington D. C. and many of the same photographs that decorated the walls of the church’s narthex, of you robed and beaming beside tiers of confirmands, teenagers in dresses or suits and ties with hair that seemed to grow in length and breadth with each successive class. In the lower right corner of each was a placard listing the name of our church, Good Samaritan Methodist, and the year of the confirmation. Three pastors had preceded you since the church’s inception in 1953, but since 1968, the year I completed my residency and first practiced obstetrics and gynecology professionally, you’d been our flock’s shepherd, and I knew no one to speak ill of you.

By turns self-deprecating and welcoming, in thick-lensed glasses that magnified your eyes to twice their natural size, you had the air of a counselor to whom much had been entrusted. I was grateful, as I’m sure you were, that most of our conversations were light. As we waited for Lorna and Bev to call us to dinner, we discussed whether the Vikings, your team, had a better chance of making the playoffs than the Packers, mine, some state and national politics but in strokes broad enough to leave the question of whether we agreed on fundamentals to the imagination, musky fishing, and church business, whether I thought replacing the carpeting in the aisles and nave a worthy investment of church capital, which I did not, or whether more money should be channeled into church youth programs, which I did. The only OB-GYN who was also a regular church member, I was the one you called upon to talk to each confirmation class about sex, not the mechanics of it, which by fifteen and sixteen all should have known, but the joy of it when shared with the right partner at the right time and, of course, the risks. Years before the outbreak of AIDS, I recited the litany of garden variety venereal diseases of which they needed to be aware and outlined the standard methods of birth control, from I.U.D.s to the pill and from condoms, diaphragms, and spermicidal jelly to sterilization by vasectomy or tubal ligation, and—while not the most exciting method known to humankind, I told them, certainly the most effective—abstinence.

If the termination of a pregnancy, also known as an abortion, was in the strict sense a method of birth control, I told them that I’d performed them only under the direst circumstances, when the mother’s life had been endangered by an ectopic pregnancy, for instance, or when diagnostic tests had detected in the fetus a fatal genetic disorder like trisomy 18 or a fatal disease like Tay Sachs, and would not perform them just because the mother, regardless of her age or station, didn’t wish to see her pregnancy through to term. This was a lie, of course. And you, who during each of my talks had sat with the kids in the living room of Yahweh House, a forest green bungalow bequeathed to the church by Delores Peacock upon her death at age 92, knew it. You knew it not because I’d confessed to you the guilt I’d felt at performing them, though I had. You knew it because both abortions—there had been two—I’d performed at your request on the teenaged daughters of prominent church members. In both cases, the parents of the pregnant girl had come to you for counseling, and while I wasn’t privy to your conversations, I’m sure you recited their options to them, including keeping the baby—it would be their grandchild after all—or putting it up for adoption. From our conversations, I gleaned that neither girl’s parents had been in favor of her seeing the pregnancy through to term. When I met with the girls themselves to discuss the procedure, neither, in truth, were they. Everyone involved, parents and patients both, agreed that to spare the girls the stigma and shame associated with their conditions their pregnancies should be terminated at the earliest opportunity, and not at an abortion clinic with Right-to-Lifers lying in wait to harangue and harass them but at a doctor’s office in an upscale OB-GYN clinic befitting their upbringings and class. And because of my reputation as a doctor and church member, you felt that I should be the one to do it.

The problem was, except in the instances cited in each of my sex talks, I had not performed an abortion on any of my own patients who had elected to have one but had referred them instead to the one partner of the eight of us at the clinic, Dr. Heath, who performed D and C’s discretely when he felt the situation required it and took, I think, some pride in the work, believing the Supreme Court ruling in Roe versus Wade toothless without physicians willing to handle the demand. In truth, Myron, my aversion to terminating a healthy pregnancy had nothing to do with the Supreme Court ruling—I believed then as now in a woman’s sovereignty over her own body—but rather in the part of the Declaration of Geneva that reads, “I will maintain the utmost respect for human life.”

All of this I explained to you, the first time in your office, the second time in mine, in the half-light from our desk lamps while we waited for our wives to call us to dinner, and both times you absorbed every word, your closely cropped head bowed toward your lap, your khaki trousers crossed at your knees, the grooves from your cheekbones to your chin carved, one never doubted, by the deep well of your compassion and desire to help those of your flock in need.

“Could you think of this, Bruce,” you said both times after I had finished, “as a form of tithing? Because that’s what it is. A tithe, an offering, a very generous gift.”

And both times that was how I viewed what I then agreed to do.

Between the first two abortions you asked me to perform and the third, six years elapsed. The church grew—our kids grew, too—and while I hadn’t washed the taste of the first two abortions from my mouth, I assumed you’d taken what I’d told you to heart and realized that despite my calling I wasn’t cut out for tithes of this magnitude. Another OB-GYN, Sunny Li, and her husband Niles, a radiologist, had moved to Minneapolis from Illinois and joined Good Sam in the meantime, and it occurred to me that perhaps you’d turned to her for assistance. Confirmation classes had more than doubled in size, such that the synod had assigned the church a youth minister to assist with the religious instruction, and the cultural endorsement of sex without consequence, ubiquitous in cinema, television, pop music, and advertising, hadn’t made being a teenager any easier.

Indeed, when Lorna handed me a copy of Hustler Magazine our younger son had squirreled away on the top shelf of his closet beneath a stack of Sports Illustrateds, I was as shocked as she by the explicit nature of the “artwork” inside—vaginas splayed open by fingernails manicured as if by airbrush, cameras positioned no further away from their subjects than I was from mine during pelvic exams, even the urethra, a speck, discernible to the untrained eye. Though I joked, “I had no idea Vance was remotely interested in his old man’s line of work,” and suggested returning the contraband to its hiding place, reluctant as I was to eradicate an outlet that, rechanneled, might lead to graver outcomes, I was saddened by the absence of subtlety, even if by today’s standards the photos might seem as antiquated and quaint as the pornographic cabinet cards my own father kept behind the bar as curiosities he pulled out for the amusement of patrons in the 40’s and 50’s.

Behind my parents’ tavern in Milwaukee, Wisconsin had stood the icehouse, and one of my jobs as a kid had been to chop ice for the wells from blocks nestled in the straw. While filling the wells from buckets one day, I told Lorna as I passed Vance’s magazine back to her, I first encountered the set of silver gelatin prints of female nudes—“naked ladies,” my friends and I called them—perched on divans as they smoked cigarettes at the ends of long holders or inserted hairpins into tresses before Baroque vanities. None of the women were entirely nude—each was draped in a bed sheet or strings of pearls—and yet once seen I couldn’t erase them from my mind, the shadowed loins, the thinly sheathed breasts and nipples, the powdered expressions of knowing nonchalance.

“So that’s why you became an OB-GYN,” Lorna said. “It all makes perfect sense. ”

It was a Saturday afternoon in the summer of 1980. The lawns were mown, front, back, and sides, the edges trimmed, and the boys had taken the Volvo, Leo in the driver’s seat, to Bush Lake to wash the grass stains from their ankles and forearms. I laughed, and Lorna did, too. Then she said, “Oh my God, Bruce, will you look at these?” and displayed a section of the magazine called “Beaver Hunt,” which featured snapshots that women from across the United States and Canada had had taken of themselves and mailed to the publisher, each with her legs parted as if by invisible stirrups, for the $150 that would be hers if her photo was run. Some sat on ratty sofas or chairs. Others rested on filthy shag. One I remember to this day lay sprawled across a child’s inflatable bathing pool, her tropical-colored bikini wadded on the grass beside her feet. At first I thought she was Katie Schnegel, an OR nurse with whom I was having an affair and, in truth, had slept that morning after rounds. Poor as the photo’s quality was, the crazy, gap-toothed, take-no-prisoners smile was Katie’s. So, too, were the brown pigtails. And yet upon closer inspection, a Jack-o-lantern’s grin of keloids at the base of the subject’s mound of Venus, presumably from a poorly incised Cesarean, differentiated her from Katie, who was childless.

Lorna, ever curious, wanted to know at which of the photos I was looking, and I tapped it with my finger. By then she was sitting in the chair beside mine at our kitchen table, squinting at the citations beneath the photos.

“Don’t tell me you recognize B.K. from Vancouver, British Columbia,” she said.

“I thought she was a patient is all,” I said. “But she can’t be, not if she resides in British Columbia, right?”

“You know who she looks like?” Lorna said. “Katie Schnegel, the OR nurse you introduced me to at the hospital.”

A month before, when the Mercedes dealership had been out of loaners, Lorna had picked me up after surgery as I was saying goodbye to Katie.

“Honestly, the resemblance would never have occurred to me, honey,” I said.

“Are you kidding?” Lorna said, “It looks just like her,” and I agreed, not about to point out the telltale scar that followed B.K.’s swimsuit line or, having by then scrutinized the image more closely, the mole on her vulva and larger-than-average clitoral hood.

Instead I closed the magazine and said, “Escarpment,” an innocent enough word that not long before had fallen outside either of our children’s vocabularies and, because Lorna and I had both liked the sound of it, was code for: Let’s make love at the first available opportunity. When our kids were younger, they, too, had delighted in the word and neither of us had felt the least compunction to give it context, both of us blurting it apropos of nothing. But as Vance and Leo matured, we had to become more sophisticated in our usage, reminiscing about the escarpments we had seen on vacations—the Mogollan Rim in Arizona, for instance, or Devil’s Slide in California—or would, we imagined, on vacations to come—the Serra da Mantiqueira in Brazil, Baltic Klint in Sweden, or Côte d’Or in France.

“Can’t you be any more original than that?” Lorna said.

“Under pressure, sure,” I said, and we retired to our bedroom, but not before returning Vance’s magazine to his bedroom closet.

In contrast to our working class parents, we saw ourselves as enlightened, and after all the talks about sex we’d had with our sons, their private lives were their business, we agreed, not ours.

The third abortion I performed at your request was on Teri, the 15-year-old daughter and only child of Glen and Myrna, who belonged to our bridge group. All four couples were members of the church, and while before and after services the wives planned each month’s bridge party, once we squared off in the four cardinal directions with our decks of playing cards and bowls of chocolate espresso beans, conversation ended, so well matched and competitive were we. Though friendly with both Glen and Myrna, I knew little about them other than that he was a tax attorney with a high-powered law firm downtown and she, unlike the other wives, worked, in her case as a French literature professor at a small liberal arts college in Saint Paul. Neither parent accompanied Teri to her consultation, which I thought strange since without a consent form signed by one of them I could not legally perform the procedure.

When I repeated this to Teri, who sat in my office in a chair across the desk from me as a clinician observed our proceedings from a second chair beside the coat tree, Teri replied, “No worries there. They’re Vulcans.”

“From Star Trek, the television series?” I asked.

“No,” she replied, “from Vulcan, the planet.”

“I see,” I said.

It was August, and I wondered if she’d attended the sex talk I’d given to the confirmation class in February. I had no recollection of seeing her there or, for that matter, ever seeing her before, not even at Glen and Myrna’s the half dozen times our bridge group had convened there. She was a pudgy thing, not from her pregnancy, for she was barely six weeks into her first trimester, but from baby fat that had retained a vestigial hold on her cheeks, arms, and thighs, all flushed from the eleven miles she’d pedaled across town on a girl’s five-speed Huffy she’d left in the waiting room propped against a ficus. A Ziggy t-shirt enveloped her like a sack, and stenciled onto the violet fabric was the fleshy, affable, long-suffering comic strip character holding up a picket sign that read, “Ziggys of the World Unite!”

“So wouldn’t that make you a Vulcan, too?” I asked.

“Technically, yes,” she replied, “though unlike Mother and Father I was born on a spaceship, and Earth is the only planet I’ve ever known. They, on the other hand, remember our home planet vividly.”

“Have they shown you photos of it?” I asked.

“Not photos in the conventional sense,” she replied. “Vulcans outgrew what humans know as photography, having developed the capacity to share memories with one another telepathically, through a phenomenon known as a mind meld.”

“And you’ve melded minds with them?” I asked.

“Oh yes,” she said, “we do it all the time. It’s how I know that Vulcan is a desert planet, far lovelier than Earth, and why we can go without water for much longer than the average human, who hasn’t had to adapt to such austere living conditions.”

“You do know you’re pregnant?” I said.

“So I’m told,” she replied.

“And why you’re here?”

“I’m here,” she said, “as a preliminary step to aborting said pregnancy.”

“That’s right,” I said.

Behind her sat the clinician, high-lit Afro wagging. I didn’t like being there any more than she did, but as a physician I believed it important for patients to understand each step of a procedure they had elected, and as I described to Teri the technique known as vacuum aspiration, I wasn’t sure Terri did. She had, after all, claimed to have been birthed onboard a Vulcan spaceship, and during my brief presentation had not so much as blinked, much less registered through facial cues that she grasped what would be done to her. Her expression was blank, and I felt less in the presence of a teenager who had gotten herself into a bind from which her parents, pastor, and I hoped to free her than in that of a traumatized psyche so deeply buried as to be unknowable without force.

“Not every patient who opts to abort a pregnancy,” I said, “can predict how she’ll feel about it later,” and recommended three psychiatrists who specialized in treating post-partum depression in patients who had lost unborn babies.

I wrote their names and telephone numbers on a prescription pad, and as I pulled the sheet from it, Teri said, “Don’t worry about me.”

“Oh yes,” I said. “I forgot. You’re Vulcan. Like Spock on Star Trek, you don’t have emotions.”

She laughed, and even it sounded mimicked, like a myna bird’s imperfect replication of human speech. “That’s a common misconception.”

“What is?” I asked.

“That Vulcans have no emotions. We have emotions. We’re simply not slaves to them, having developed highly refined methods of controlling them.” She smiled at me as if with great compassion. “I understand that this is hard for you, Dr. Holcomb.”

“I don’t perform abortions,” I said, “except—”

“I know,” she said.

“How?”

“The confirmation class, remember?”

Unlike the two teenagers on whom I’d performed abortions in the past, girls whose bodies had matured early and who, from the vantage point of having gotten pregnant, spoke with authority about the pressures they’d experienced, the temptations to which they’d succumbed, and the gravity of the decisions they were making, Teri might as well have been discussing a tonsillectomy.

If I was able to hide my agitation, the clinician was not hers. “What I’d like to know,” she said, “is whether that baby you’re carrying is Vulcan or not.”

Teri turned to her. “Of course, it’s Vulcan. I’m Vulcan. I was born into a Vulcan household.”

“But how many Vulcans do you know, honey,” the clinician asked her, “outside of your immediate family?”

“None,” Teri replied.

“So it isn’t even half human?”

“Not even half.”

I brought the consultation to an end by reminding Teri that the State of Minnesota required a parent’s signature. Teri assured me that her father would fax the consent form to the clinic from his office and, low and behold, it was waiting for me in my mailbox, signed by the relevant party, when I returned from walking Teri back to the waiting room.

That afternoon I fired the clinician for insubordination. She hadn’t worked for us long, six weeks tops, and I no longer remember her name if, indeed, I ever knew it.

“Do what you have to,” she replied as she collected her things from the lab, “but that poor child was raped. By someone she knows all too well.”

“We don’t know that she was raped,” I replied, though I knew it the same as she.

What was more, Teri knew that we knew it, for both the clinician and I had seen the flutter of panic as it came to her, what she’d admitted.

A few weeks later I came home from work to find my family seated at the kitchen table staring at a wrinkled flyer. September had arrived and the boys were back in school, Leo in 12th grade, Vance in 10th, and while I’d enjoyed horsing around with them all summer, Lorna had confided to me that she was ready to have the house to herself again. Leo captained the cross-country team, Vance played tight end on the Junior Varsity football squad, and from 7:30 in the morning when I dropped the boys off at school until 5:30 in the evening when the friends of theirs who owned cars brought them home, Lorna’s weekdays were her own. Never one to complain, she was less high-strung once autumn came, and over the years I’d come to associate the reds and yellows of the elms, oaks, and maples, through which sunlight filtered in resplendent hues, with domestic tranquility if not bliss. Not only that, Leo had been accepted into the U.S Naval Academy in Annapolis as a midshipman, having—on his own recognizance —solicited a letter of nomination from then-U.S. Congressman Al Quie in the months before Quie was elected governor, and with the money I’d set aside for his college education I’d put a down payment on an A-frame cottage outside Hayward, Wisconsin, the self-proclaimed musky-fishing capital of the world.

The lakefront property, bordered on the north by the Chequamegon National Forest, included a dock and the previous owner’s Crestliner fishing boat, rigged with a 90-horse outboard and in-dash sonar fish-finder, and at night as I fell asleep I imagined the lunkers that would surface for my plugs, spoons, and crank-baits. The previous Sunday Lorna had cancelled our upcoming canoe trip down the Saint Croix River with your family in order to spend the weekend “beautifying” our new lake place, an effort to which I hoped to add a trophy that, from snout to tail, would span the length of the fireplace mantel. What made me giddier still was the distance it would put between you and me, for the get-away would mean missing a Sunday worship service for once.

Though the abortion had gone well enough, with Glen having taken off time from work to accompany his daughter to and from the clinic, afterward I felt as if I’d not only ended a human life but destroyed criminal evidence. Without DNA samples from Glen and the fetus, for which one would need a court order, there was no way to establish paternity, and from this alone I derived solace. For his part, Glen, distracted and fidgety, provided none, and I wondered what Teri had told him about her consultation. If he was guilty and knew that I knew it, I predicted he and Myrna would leave our congregation and bridge group, and though I didn’t know it on the evening that Lorna, Leo, and Vance sat me down at the kitchen table to show me the notice Vance had removed from a telephone pole three doors down from our house, they already had.

The flyer had been crudely made, the lettering cut from newspaper headlines and pasted onto a page that had then been photocopied.

dR. BrUCe HoLcoMb, m.D.

YOUr NeiGhBorhOod AboRtioNISt

StOP iN foR yOUR freE ConFIDeNtIal cOnSultATioN

NO jOB toO sMAll oR ToO bIg!!!

At the bottom of the flyer were the addresses of my home and office as well as the telephone numbers where I could be reached. In the middle was an illustration, taken from an anatomy textbook, showing a baby, its eyes closed in slumber, nestled in the womb.

“Dear Lord,” I said.

“They’re up all over town, Dad,” Vance said. “So far Leo and I have ripped down more than fifty.”

“The first one I saw was five miles from here,” Leo added, “on a run. We need to report this to the police.”

“We will. We will,” I said, enveloped by something resembling shock. I say ‘resembling’ because I was as calm and cognizant of what was happening around me as I was in surgery, when all eyes but the patient’s were trained upon my gloved hands as they cauterized, excised, and sutured within a narrow opening. Yet I was also removed, as if observing myself from a distance, the way I, too, in surgery watched my hands, as if they, and not I, were responsible for the operation’s success or failure.

“It’s slander,” Vance exclaimed. “You don’t perform abortions.”

“You’re right, I don’t,” I said. “Not usually.” It was gratifying that Vance, too, had been attentive during my sex talk.

“What do you mean, ‘not usually’?” he asked.

“I’ve performed three,” I said, “in twelve years of practicing medicine.”

I said it not to redeem myself, for in truth I felt about what I’d done as he seemed to, his cheeks as flushed with outrage as they were when refs overlooked an opposing team’s penalties, but rather to hear what God would hear if He in his infinite compassion existed, which I doubted.

“You shouldn’t have performed even one,” Vance said. “That’s what you said.”

“That is what I said.”

“Then you lied to us,” he replied. “Why did you lie?”

I had no answer for him. In time, Leo said, “Give Dad a break, Vance. I’m sure he had his reasons.”

“Go fuck yourself, Leo,” Vance said.

“Hey!” I scolded him. “That’s no way to talk to your brother.”

“No, Vance, you go fuck yourself,” Leo said and slugged him in the arm.

When the boys were younger I would wash their mouths out for using less vulgar verbiage, but they were too old for that now, and I felt as if I, at the root of their disagreement, were powerless to rectify it. Lorna’s head was bowed. I did not discuss medicine with her and assumed she was as disturbed as Vance was by my confession. Raised in the Methodist tradition, she had never not gone to church and, before we were married, insisted our children be raised Methodist too. Upon first settling in Edina, she found Good Sam in the phone book, and from then on I mouthed the prayers and hymns, took communion, and wrote checks to the church that, I assumed, were as large as any in the offering plates. If the community’s affluence was reflected in the deep pockets of the congregation, many of my patients were church members, and in my more cynical moments I thought of the amount I gave to the church as my advertising budget.

Lorna looked up and said, “Let’s go to The Embers,” a dimly lit Twin Cities franchise that offered booth seating in a burnt umber décor and a crosshatched New York strip, baked potato, and wedge salad for under seven dollars, and there was one not five minutes away, just off the freeway next to a Howard Johnson’s. Lorna hadn’t started dinner, so we four piled into the Volvo as we did on other family outings, and in this soon-to-be defunct local institution had our last supper. Lorna ate mutely, and in time, I feared, I’d hear what she thought about what I’d done, but upon our return, after we’d played back all the answering machine messages from anonymous callers informing us that I was going to Hell, after the boys had retired to their bedrooms to finish their homework amidst all the phone ringing, Lorna and I lay in bed wondering if the ringing would ever stop, for by then the answering machine had reached its storage capacity and we’d resolved not to answer the phone again. Between rings, Lorna turned to me and told me that she knew Katie Schnegel and I were having an affair, that she’d observed me kissing Katie on the lips outside her apartment that afternoon and swanted a divorce.

“Why, Bruce?” she said. “Why?”

I could’ve fought to save our marriage. I could’ve told Lorna that Katie and I had broken up earlier that day, which we had, that the kiss we’d exchanged had been that of lovers acknowledging irreconcilable differences, which it had, and that the affair had been a one-time deal, which it hadn’t, but I didn’t.

The phone rang again, and I said, “Because when I’m in bed with her I feel like God.”

“Then I guess ‘God’ doesn’t live here anymore,” she replied.

I retired from medicine a year later, my heart no longer in it. Since then, I’ve lived a more or less ascetic life on Ghost Lake in the A-frame I bought in the weeks before Lorna and I divorced, and from April through October I fish for muskies. There are big ones in the lake, some thirty yards beyond the railing of my redwood deck and framed by balsam, birch, spruce, and hemlock that form a natural arbor through which, with binoculars, I can see who’s fishing the south slough. I’ve hauled in plenty over the years, though none as large as the one I’ve observed on still evenings lurking a few feet beneath my plug as I’ve jerked it across the surface to affect the appearance of prey. All the muskies I’ve caught up here I’ve returned to the water—the meat is palatable but packed with tiny, translucent bones and, once lodged in the throat, are difficult to extract—and I worry that the trophy fish I can see off the side of the boat, a six-foot-long, missile-shaped shadow I would mount above my fireplace if I could, remembers my landing it before, that something about my particular style of spin-casting reminds it of traumas past.

Lorna thinks I have too much time on my hands. At least that’s what she tells me when we talk on the phone every month or so. She may be right. Always we have a lot to talk about, our sons, whose accomplishments never cease to amaze us, and our mutual friends, most of whom we met through Good Sam. Though we rarely speak of our shared past, it’s never more immediate than after one of her phone calls. Then the man I am at seventy-five must reconcile himself to the man he was at forty-four, when our marriage ended and I left the church and OB-GYN clinic for good. Probably I wasn’t meant for matrimony. But until one has tried it, how does one know? I tried it, loved it, and would’ve continued loving it if only I could’ve slept with any and all OR nurses who wished to sleep with me, be they fat, thin, wide-hipped, slender-hipped, white, black, brown, or tangerine, my only stipulation being a sense of humor to compensate for my lack of one. Before Katie Schnegel there had been many, each funny in her way, and after her none.

What happens in a surgical theater stays there, and yet, for me, no sex was ever as scintillating or as satisfying as that with the nurse who had been in it with me, who’d handed me the very instrument the moment required, the particular scalpel, clamp, forceps, tenaculum, or retractor without my even having to name it, as if for the duration of the vaginal hysterectomy or the removal of the ovarian cyst she and I had read each other’s minds. That’s how it had been with Katie and me until she blurted out at the end of a successful, if taxing, myomectomy, as I was sewing the patient up after removing more than a dozen fibroids, “I want to have your baby, Bruce.” The anesthesiologist, a burley, bearded, bear of a man, laughed through his mask, as did I as I thanked her, for her tone had been that of one delivering a punchy compliment, glibly admiring of the feat I had performed. I didn’t think about it again until later that day when, lying spent beside me, she said, “I wasn’t kidding earlier.”

“About what?”

“Your baby.” She turned onto her side on the bed so that her pigtails stuck out at angles like those of an Arrow-Thru-The-Head, a popular novelty at the time. “I’m going to have it, Bruce.”

I asked Katie if she was pregnant, and she told me, “A month.” She’d stopped taking the pill three months before, and for the three days she’d known the test results, she’d been too frightened to tell me.

“I’m not asking you to marry me. I’ll raise the child myself. You won’t be responsible to it in any way, Bruce. I just really, really want a baby. Your baby. And, I guess, your blessing.”

Katie had gone rogue, and yet I felt oddly at peace, just as I did in the church sanctuary surrounded by stained glass and before me on the altar the cross rising into the airy heights of the chancel as if from a garden in full bloom. Before making love, I’d told her about the abortion I’d performed earlier in the week.

“The girl, fifteen,” I said, “had likely been raped by her father, a man I play bridge with, and frankly, I don’t know which to feel worse about, the taking of a human life or the destruction of criminal evidence.”

“Perhaps this is something you should take up with your pastor,” she replied.

“He was the one who convinced me to do it.”

“Maybe you should convert to Lutheranism,” she suggested.

“But Reverend Noonan is a good man,” I said. “He was only protecting his flock, doing what he thought best.”

Now, after lovemaking, Katie sat up in bed and said, “Perhaps you could think of this as returning stolen goods, a life we’re bringing into the world to replace the one you took.”

I wasn’t about to tell her about the other two abortions I’d performed for fear she’d want three kids from me instead of just the one. “Have you spoken to your doctor about options?” I asked.

“What options?” she replied.

“You know,” I said. Though I didn’t perform abortions, many doctors did, a D and C as effective and safe for early miscarriages as early unwanted pregnancies.

“You’re kidding, right?” she said. “You have got to be fucking out of your mind.”

“I have to go,” I said.

“You can’t leave,” she said.

As usual our clothes were scattered across her bedroom floor. I pulled a dress sock over my calf. “If you go through with this,” I said, “our relationship is over.”

“It’s already over. You’re married. I know. How convenient for you.”

By the time I was back in my suit, she was waiting for me by the door in an open robe, clothed from sternum to knees except for a strip down the middle of her the width of her neck. She followed me outside onto the walkway that looked onto the parking lot and street.

“You can’t be out here like that,” I said. “What if someone sees you?”

“I’m letting you off the hook. The least you can do is kiss me one last time,” she said, and as I did, I closed her robe and cinched it tight.

September is the best month up here, ask anyone. Muskies, fattening up for dormancy, are less discerning than at other times of the season and when striking a surface lure explode from the lake fanning their tails. Their returns to the water are just as spectacular, cannonball splashes that resound to the mottled shorelines. The air lumbers, encumbered by the smoke of burning leaves, except when the Packers are playing, and everyone holes up in front of their TVs. When Rogers connects with Nelson in the end zone or Lacy runs the ball up the middle for a touchdown, the chambers of shotguns and rifles empty into the sky, my own among them, and the reports echo across the lake.

Though you and I went our separate ways long ago, Myron, Lorna and Bev are still in touch, and it’s through Lorna that I know anything about you and of what your life consists, that you retired from the ministry more than a dozen years ago and moved with Bev to a condo in Saint Augustine, Florida. Good for you! Every July when you and she return to the Twin Cities for a week of catching up with old friends, Bev shows Lorna a stack of photos of you and her posing with your daughters, sons-in-law, and four grandchildren before landmarks in the oldest continuously occupied European-established settlement in the continental U.S.—the tourist district and its Spanish colonial boutiques and bistros, the beaches, harbor, fort, and lighthouse—and asks her to guess which one you’ve chosen for your Christmas card. Lorna always guesses wrong, basing her selection on the artistry of the composition—the scenery, light, and contrast of colors—rather than on the number of grandkids smiling, Bev’s sole criterion.

Every year, Lorna tells me, you and Bev try to persuade her and Lincoln to buy a little place down there, a condo like yours with an ocean view or, at least, a view of a cypress-lined fairway, the idea being that if only she lived in a popular tourist destination, our boys, their wives, the six kids they have between them, and I, who unlike Lorna did not remarry, would want to gather for reunions once or twice a year like your family does. But what neither you nor Bev can seem to grasp is that no one in my family, except perhaps the son or daughter I’ve never met, enjoys spending time together as a family, despite how we appeared prior to my termination of Teri’s pregnancy, and the onslaught of Right-to-Lifers it brought to the doorstep of my residence and workplace, forcing me out of the house and into an apartment more quickly than either Lorna or I anticipated, even after we’d shared with Leo and Vance our decision to separate.

Imagine waking before dawn to a man or woman—it doesn’t matter which—telling you through a megaphone that God loathes the sight of you, that to Him you are an abomination, that a seat between John Wayne Gacy and Josef Mengele has been reserved for you at Satan’s table. The sky lightens on a peaceful assembly of between five and twenty planted at the end of your driveway, at your property line, waving signs calling you Doctor Death and poster-sized laser prints of fetuses. More protestors await you at work, among them a minister in a clerical collar quoting scripture from a soapbox. As you pull open the door of plate glass, he points a finger at you, bellows, “Your hands are full of blood!” You wonder why you should be targeted rather than your partner, Dr. Heath, who has quietly terminated dozens of healthy pregnancies at the same clinic where you have terminated exactly three. But you know why. Though you can’t prove Teri is behind the flyers that reappear as quickly as they’re torn down, you know she is the culprit, that she is making you pay not for the human life you took but for the secret you made her spill.

If I tried to set up an appointment with you to discuss my situation—and I did, to no avail—I no longer hold you responsible for the ruination of my career and family. Lately I learned from Lorna of your imminent decline, your memory lapses, which, Bev tells her, are growing longer and more frequent, and of Bev’s worries about having to commit you to an assisted living facility, which she believes will kill you. Probably the time to ask for an apology has passed—you’re eighty, your life’s work complete—but if I did, would you say, “I’m sorry, Bruce,” or would you ask me why I chose to perform the abortions? Why, in particular, I performed the third one when I knew from performing the first two that it would violate my moral code?

“Because, Myron,” I would tell you, “I placed your moral code above my own, believing a Methodist pastor closer to God.”

“But you told me yourself,” I can hear you saying, “that you don’t believe in God, Bruce.”

And you’re right, Myron, I don’t, which leaves me again with the unsettling feeling that I performed all three because I liked you, because I valued your friendship and didn’t want to lose it, and in particular didn’t want you running to Sunny Li, the new OB-GYN in town, a church member, and a woman to boot, to ask her to do what I couldn’t.

But what am I to make of your utter dismissal of me at the time I needed you most? Despite the old chestnut about doctors having god complexes, I am no god and cannot bring myself to forget. You will have the luxury of forgetting soon enough, a silver lining in your situation. Or perhaps you don’t dwell on such matters. Why would you? For all our perceived closeness, I didn’t know you beyond what I projected onto you, a dynamic most doctors know all too well.

Of course, all of this happened long ago, those marvelous dinners our families shared, when our kids jumped on our trampoline until they tired, then lay on it staring at clouds or, if we were visiting you, played croquet until sundown when off they’d dash with Mason jars in search of fireflies that illuminated the ancient willow beside the creek that edged your lot. Across town from each other, you in old Edina, we in new, our homes were close enough to outdoor skating rinks that our kids could walk to them from November to March and return for supper so exhausted and ravenous that after coffee, when it was time for our families to part, we’d find all four passed out in front of the TV, not even “The Wonderful World of Disney” able to keep them awake.

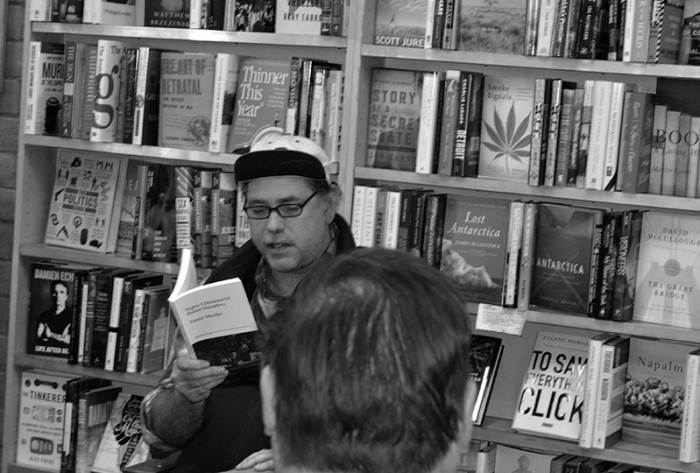

BIO

Daniel Mueller is the author of two collections of short stories, How Animals Mate (Overlook Press 1999), which won the Sewanee Fiction Prize, and Nights I Dreamed of Hubert Humphrey (Outpost 19 Books 2013). His work has appeared in numerous magazines and journals, including The Iowa Review, The Missouri Review, Story Quarterly, The Cincinnati Review, Prairie Schooner, CutBank, Joyland, Surreal South, Another Chicago Magazine, The Mississippi Review, Story, The Crescent Review, and Playboy. He is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Massachusetts Cultural Council, Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Henfield Foundation, University of Virginia, and Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He directs the creative writing program at University of New Mexico and serves on the creative writing faculty of the Low-Residency MFA Program at Queens University of Charlotte.

Daniel Mueller is the author of two collections of short stories, How Animals Mate (Overlook Press 1999), which won the Sewanee Fiction Prize, and Nights I Dreamed of Hubert Humphrey (Outpost 19 Books 2013). His work has appeared in numerous magazines and journals, including The Iowa Review, The Missouri Review, Story Quarterly, The Cincinnati Review, Prairie Schooner, CutBank, Joyland, Surreal South, Another Chicago Magazine, The Mississippi Review, Story, The Crescent Review, and Playboy. He is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Massachusetts Cultural Council, Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Henfield Foundation, University of Virginia, and Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He directs the creative writing program at University of New Mexico and serves on the creative writing faculty of the Low-Residency MFA Program at Queens University of Charlotte.