The Opposite of Suicide II

by Kyle Mustain

The essay is obviously the opposite of that awful object, ‘the article’…

—William Gass

Over the years I formed this dream about my writing. Not a hard goal, like wanting to have a book published by age thirty-five. Instead my dream was immaterial: I wanted simply to know the feeling of being approached by a stranger, to say, “I’m sorry, but I just wanted to take the chance to tell you, I love your work.” After I published “The Opposite of Suicide” in the December 2014 issue of The Writing Disorder, that dream finally came true, many times.

I spent three mostly sleepless months researching, writing, and editing the essay I am most proud of. Then I spent over a year trying to get it published. When it finally hit the Web, nothing much happened at first. Then, about a month later, some parties discovered the essay, and used it to have me fired from my job as a substitute teacher. After I was terminated from my position, the essay went micro-viral, which means it was passed around a lot, among a very specific set of people—namely people from Central Illinois; people who lived near or had originally come from my hometown of Galesburg, Illinois.

I had mixed emotions about this, as I was glad my work was finally being read, but I did not believe I deserved to be terminated for it. As it happened, my dream did finally come true. People, most of them students at Galesburg High School, approached me in public.

Only what they said to me was: “I loved your article.”

Let’s get some things straight. The school district that fired me was not the same one I wrote about in the first essay. The school district that fired me was a rural community outside of my hometown. I had taken a position as a long-term substitute teacher practically over night after a teacher gave her resignation. It is still unclear to me why she left, but I know some controversy surrounded it, and that her resignation was asked for by the school board.

Before I move on there are still more things to clear up. In the first essay I kept the name of my hometown a secret. All of the identities of persons not related to me were given new names. With the exception of the underage students, I did not have to do this. I did it to maintain people’s anonymity. It was my piece of writing, my work, my opinions, and I didn’t want to muddle things for anyone else. I went to great lengths to conceal the name of my hometown and the school district for the aforementioned reasons, but most importantly to the points I was trying to make in the original piece: I wanted the message to come across that this could be anywhere in Small—or Medium—town, USA.

A major point I would like to make is that practically none of the first essay was about Lombard Middle School. That is the school I lived closest to when I was substitute teaching. I worked there probably 90% of the time I was subbing. No one who works at Lombard should feel like anything in the first essay was directed at them. I adore everyone I worked with at that school, both in the classrooms and the office. Truly, I felt at home there and believe that is the best school in all of the district.

More things to address: After I was terminated from the rural school district, I did call the personnel coordinator for my hometown school district and asked if I could have my old job back. She inquired the head of human resources. Within a few hours she reinstated my registration as a substitute teacher for Community Unit School District 205. The coordinator scheduled me for a date three weeks off. The first thought that popped into my head was, I have three weeks to find a new job . . .

A few days later I called her again and quit, even without having a new job.

Last item to address: In case there are any students of District 205 who are still confused: No, I did not commit suicide. I am very much alive, well, and living in New York City.

Let’s begin.

Operation Save Silas

This is a letter I wrote to the editor of the Galesburg Register Mail in early 2014:

Over the weekend a group of concerned citizens met to discuss alternatives to tearing down Silas Willard. When the question was asked, why the School Board would want the community to invest in a new building designed to only last 20-30 years, I cracked a joke, “They’re probably looking ahead to the future because in 20-30 years hardly anyone will live here anymore.” The room erupted in laughter, which quickly hushed into awkward silence. On our current path that could very well be the city’s future.

I moved back to Galesburg in the fall of 2012 after a twelve year absence. It has been my pleasure to serve this community as a substitute teacher for District 205 over the past year. As we near the summer, I am faced with the decision of whether to stay here. I have friends all over the world begging me to come live in their cities. New York, Chicago, Portland, these places all entice me. But I’m constantly giving Galesburg the benefit of the doubt; the chance for her to redeem herself to me.

One young couple I befriended in grad school relocated to Bloomington, Indiana. Now, parts of that city are as redneck as you can get. But others are quite simply stunning. Take a drive around that city and you will see historic buildings and schoolhouses, all preserved and modernized. Not just around the university, but the whole city has this vibe like things are actually happening there. That community has committed itself to maintaining a standard of beauty that cultivates a pleasant, inviting environment.

It is my belief and the belief of many people in this community that Silas Willard and buildings like it create that kind of pleasant environment within Galesburg.

At this meeting I attended over the weekend, two young couples living in the Silas Willard neighborhood said that school building was a major attraction to settling their families in Galesburg. Both young couples expressed that if the building were to be torn down, they would begin plans to relocate.

What I’m getting at is destroying landmarks like Silas Willard gives outsiders the wrong impression. If anything, it shows that we don’t care enough about our history to try to preserve it. There are less and less things that make Galesburg unique. Why would anyone from outside want to move here when it continually tries to make itself look like everyplace else? For that matter, why should anyone stay?

Urban Sprawl and Push-and-Pull

Think of this way: building outward and upward; building anew instead of reusing what’s already in place; corporate chains coming in, buying land cheaply instead of having to pay rent in preexisting structures, building their cookie-cutter stores instead of opening shop in unique, unused storefronts. After time, the cities who let this happen become littered with mini-malls (ironic play on “minimal,” ever notice that?). It isn’t long before these retail spaces, cheaper because of their lower overhead, take prevalence over the older buildings. Stores move out of the older buildings, leaving them uncared for so they end up becoming condemned.

Mini-malls and cookier-cutter franchise buildings look cheap because they are. They look sad and lacking in character because, well. And that is precisely the type of building going in as the new Silas Willard.

From a US Department of Agriculture Pamphlet:

. . . total rural population has declined slightly for several years, as slowing natural population growth fails to offset net migration away from rural areas; this is the first time rural population declined since data became available in 1950 that could detect such a trend. At the same time, long-term trends continue to concentrate the most highly educated members of the working-age population in urban areas where the personal economic returns to higher education are greater.

This paragraph is extremely important. What it basically says is rural population in the US is decreasing, and that those who come from rural communities, then earn higher educations are choosing not to return to their hometowns. Keep this in mind throughout this essay.

15% of the US lives in rural or “non-metro” areas. That means people who call rural America “The Real America” are way, way mistaken. And since the Great Recession people have been migrating away from rural areas. Galesburg, with a population of 32,195 is just big enough to be considered a city.

However, despite the lower earnings available in rural areas, some individuals and families do migrate from urban to rural areas at all levels of educational attainment, as quality-of-life factors, lower housing costs, personal ties, or other specific opportunities motivate them to move or move back to rural America.

After I returned to Galesburg, I made several friends who grew up in inner-city Chicago or St. Louis, who actually chose to move to Galesburg because of reasons listed above. They saw greater opportunity for themselves in a small city than in the big city. So, there is interest for people from the metropolises to move to communities like Galesburg. Why not take advantage of that?

According to this study, education has a lot to do with the success of an area. It’s a no-brainer that we should be investing heavily in improving education. But currently there are cuts on education which puts us at an impasse.

The largest factory in town, Admiral (which became Maytag in the 90s), left in 2003. Let me just say there are many ways to court a company to set up in a town, but it can’t all be based on smooth-talking. The people who built those companies and run them got where they are by being shrewd. And when they do their research and find something as simple as the school district continually making poor choices with its money, it’s an easy conclusion that they are going to have trouble drawing talented workers to live there, so they decide not to take the gamble.

It’s a vicious cycle we’re on: Nobody wants to move there because nobody who lives there even wants to be there. I read essays and articles all the time by other writers whose hometowns are going through the same thing. And yet these small towns keep making the same mistakes over and over. Something trite should go here, some Horatio Alger shit about making America great again, but I’m pretty sure that isn’t right, either. I’m sorry, but ‘Murica just isn’t working.

The fact that we even have such an idiotic term as ‘Murica is indicative of a split in the American identity. We fight over this. How can we be unified on anything if we can’t even agree on what we are anymore?

| Factors of Migration |

Push Factors |

Pull Factors |

| ECONOMIC |

Emigration away from area with few job opportunities |

Immigration to areas where jobs are more available; areas with more valuable natural resources, or new industries |

| CULTURAL |

Forced migration has occurred for these main reasons: slavery, political instability, and fear of persecution. |

People are attracted to democratic countries that encourage individual choice in education, career, and place of residence. After Communists gained control of Eastern Europe in the late 1940s, many people in that region were pulled toward the democracies in Western Europe and North America. |

This is adapted from a chart on the Lewis Historical Society website. [http://lewishistoricalsociety.com/wiki2011/tiki-read_article.php?articleId=28] It breaks down the main factors influencing what is known and the “push-and-pull factors” of migration.

If the trend of push-and-pull migration away from rural areas is not a primarily economic anomaly, then the problem these numbers aren’t telling us is why people choose to move away from Rural America. This is not an inconsequential number—We are talking tens of millions of people fleeing their hometowns because of ignorance, bigotry, and hypocrisy. If we were to record all of these untold stories, just imagine what kind of impact it could have—to finally hold a true mirror up to the real ‘Murica and show it how ugly it really is.

This phenomenon isn’t unique to Galesburg. It happens in places like Quincy, Pekin, Elmhurst. The list goes on of these fuck-up towns. They become self-homogenizing. Then they run themselves into the ground because of their lack of diversity.

When I was working on a piece about Carl Sandburg, I wanted to explore this idea a little more closely. I wanted some facts and figures, nothing too overwhelming, but a good sampling. I called the record keeper at Galesburg High School, informing that person I was an alumnus working on a paper for grad school. I asked if I could just have the list of the student rankings from the class of ’99, thinking surely this person could pull that info up quickly. She said she would do it, but I think once she got the sense of what I wanted the information for, she never sent it to me.

Now, Dad would have been all “Freedom of Information Act” on her and submitted a formal request. But I let it go. Besides, all getting that data would have done is confirm for me my suspicion: The top performers in my class did not return to Galesburg after getting college and post-graduate degrees.

In short, every year towns like Galesburg are losing all of their intelligent people. This says many things, and this information could be hit from several different angles to extrapolate all the different factors for why people choose not to go back. But I think it’s safe to conclude that this is indicative of a place that does not value intelligence.

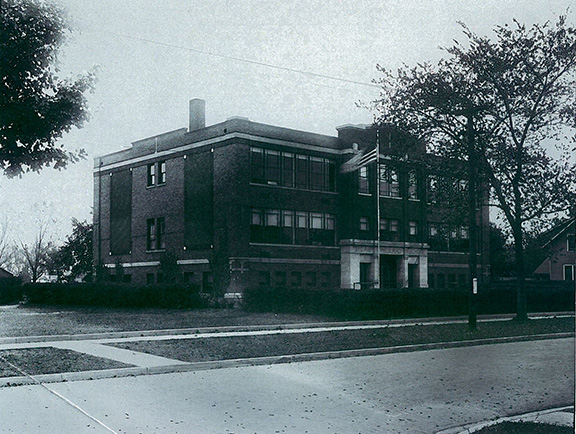

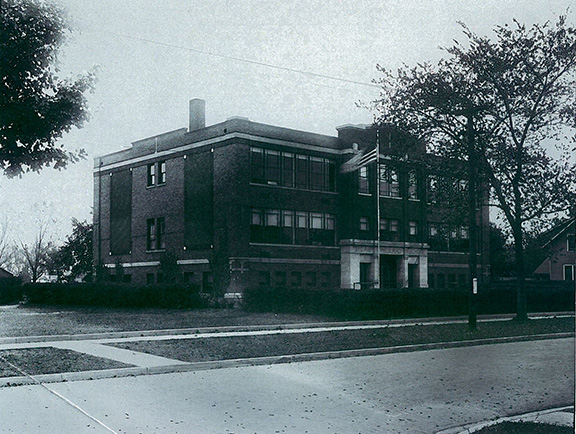

Notice the repeating forms of rectangular geometry, perfectly parallel, and perpendicular lines. Buildings like Silas Willard that were part of the Prairie School Movement were visual odes to the landscape; designed to look as if they were part of the prairie landscape themselves. Unique, it can be truly said there is nothing quite like them in the rest of the world, and there are precious few left.

School Board Face-Off

That letter to the editor of The Register Mail was never sent in. My father advised me not to. After he read it, he expressed his concern that sending that letter might endanger my job at District 205. The way he put it, “If the board members or any other high-ups read this and take it the wrong way, they could make your life very difficult—I wouldn’t put anything past these people.”

Well, I got nothing to lose anymore.

When the school board members strolled in for the special meeting over Silas Willard Schoolhouse, I was immediately struck by the grotesque image of fluorescent light bouncing off a row of pasty white skulls. Many of the board members and high-ups of the school district are facsimiles of the same archetype: pudgy bald white men way past their primes. I don’t have much of a place to speak, my grandfather was also a bald white man on the school board well past his prime. But that was also fifty fucking years ago.

Since the mid-1990s my father, Douglas Mustain, has been saving my childhood elementary school from being torn down. It repeatedly comes before the school board as if it is “a decision that has to be faced.” No, the building is perfectly sound, and would remain to be so for at least another forty years.

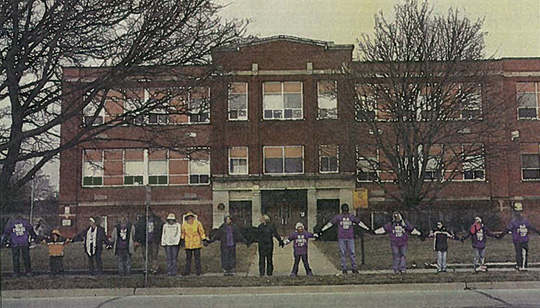

In 2006 he, my mother, and several other members of the community went to the school board with a well-researched argument he wrote titled PRESERVING SILAS WILLARD. The board limits public comments to three minutes at the podium. So, my father began reading from the document. When his three minutes were up, my mother, Sharon Mustain, stood up at the podium, stated her name, profession, address, then began reading where my father had left off. When my mother’s time was up, another member of Operation Save Silas stood up, gave her name, profession, address, then read from where my mother had left off. Members of the group followed in this fashion until the entire 8-page document was read aloud before the school board’s reluctant ears.

Whenever I read over that document, I love that my dad kept hitting the point that if the district chose to renovate the schoolhouse instead of build anew, they would have money left over in case they wanted to make some cool additions, really pimp the place out. That year Operation Save Silas was able to postpone the demolition of the building, yet again.

But, the school board was not finished with Silas yet. In the fall of 2013, they voted to destroy and replace the building. My father was outraged because they made the vote brashly and with no opportunity for the public to voice their say in the matter. An earlier iteration of the board had determined the vote would go to referendum. But, when a new superintendent of finance and interim superintendent of schools came in, they changed it to a board decision, taking the public’s voice in the matter out of the equation.

So, in the spring of 2014, we and many disgruntled community members got together every Saturday to brainstorm ideas for how to bring the school board around to our way of seeing things. We got the board to agree to hear us in a special meeting set for April 7, 2014.

It had been a busy week. My father and other members of Operation Save Silas met with each board member individually, suggesting what could be done with the $11 million the district would save by simply renovating. The more they appealed to their senses of reason, Dad began to feel a few of the board members had turned their minds.

All we needed was someone to make a motion for a vote. A majority vote would save Silas once and for all.

When the public comments time was over, every single board member made a statement about the schoolhouse. One remarked that previous iterations of the school board, going all the way back to the 90s, were “faced with the decision” regarding whether to tear Silas down because of its numerous life safety issues and poor conditions (which was actually all due to deferred maintenance). As he saw it, “this can had been kicked down the road several times,” and now it was this board who would finally bury the hatchet in this ongoing problem that is Silas Willard Schoolhouse.

Others from the board lamented that they had already voted on this matter the previous fall. By holding this special meeting, they were in fact doing us a favor, and going against protocol. So, a couple board members stated that overturning their decision would “damage the board’s credibility.”

That seemed to be the angle the board decided was best to play—that to save face, they could not possibly go back on a decision they had already made. Those of us pleading with them were simply too late. We should have been there in October, even though the board slipped that earlier vote by us.

The board president spoke and actually commended us community members for our hard work and time invested in contacting the board members. This inspired rousing applause from my fellow Operation Save Silas members. I could not bear to put my hands together for this man. We’d met a few times while I had been subbing, although he never bothered introducing himself to me. I guess by his expensive-looking overcoat I was supposed to just assume he was somebody important. He has a goatee, I have a beard. There’s definitely a divide between the kinds of people who wear goatees and those of us who wear beards—I know a tool when I see one.

He played aloof when he asked the district attorney whether there needed to be a vote. They both put on this spectacle of befuddlement; the district attorney shuffled some papers as if he was at that moment looking up the bylaws. He said, “This has never happened before,” then explained to the room that since the decision had already been voted on the past fall, there would have to be a motion by a member of the board before they could vote on the matter again.

The board president raised his eyebrows like he was so surprised and concerned that to go back on their vote would be such a major undertaking, going against all that important procedure stuff that they held so dearly. But, as if it was a favor to us hard-working constituents, he said he supposed he could put it to the board to ask if any of them would like to make the motion to have a revote on Silas Willard. Eyes darted from board member to board member. They sat back in their seats, pushed themselves as far away from their microphones as possible. Their faces directed downward to the table.

Meeting adjourned.

We got fucking played.

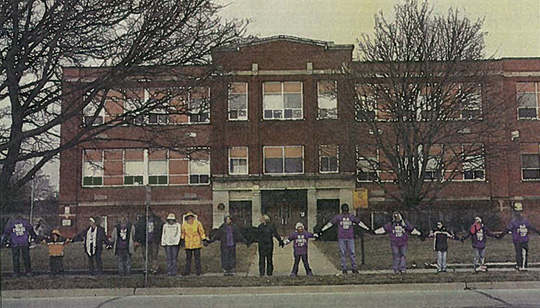

From the newspaper in 2006 when the community successfully saved Silas Willard from the school board’s wrecking ball. Gotta say, it’s pretty badass to see one’s parents in a human chain.

I Love My Hometown. Some of My Best Friends Are Buried There.

I didn’t actually hate growing up in Galesburg. I hated growing out of it. I hated that there was a gradual awakening that took place by my teen ages, that the person I was on the inside was at conflict with the person I was on the outside, which was the perception people had of me and the way I was expected to be. It’s hard to prove that, of course—what people’s expectations are of you, but there is unspoken mojo that goes on between people. It’s indirect. People say homophobic, racist, and otherwise bigoted things. Even though they may be directed at a third or more often fourth never-present party, it is a warning to everyone in immediate presence.

The underlying power of that message is that by striking out on your own and voicing your dissension with the popular opinion of those you are among, you run the risk of losing everything you have ever known. You will no longer belong. You will become isolated. And there’s great power in threatening someone with isolation.

This is a stupid fucking way of going about life.

I don’t hate Galesburg, but I don’t love it, either. I both love and hate it. There are places I love going there. There’s not a lot, but it has its charm. I hate most of it. But I do enjoy that the people who live there and I have common background. There are stories we can share, things we can all laugh about. I just hate how people seem to have cut themselves off; the way the rest of the world is advancing, but they aren’t.

So what do you do when you move back to your hometown that you feel ambivalent towards? As I found out in the first couple months after arriving, work was clearly not an option. There just weren’t any jobs in the area. My move to Galesburg was meant to be a short layover to get reacquainted with family and old friends. My dad needed some help at his law firm scanning about thirty-five years’ worth of paper files into PDFs. Problem was, he couldn’t afford to pay me very much. So, I started subbing to make some extra money. Then that turned into a full-time job.

It was a delight to get to spend more time with my family. With the exception of my younger sister, my parents have an empty house these days. I had just spent four years in North Carolina attending school and figuring out what kind of writer I wanted to be, albeit a mostly unsuccessful one. When I moved back I was certainly jaded from my experience in grad school and had developed a cantankerous attitude toward anyone who didn’t agree with my worldview. I arrogantly snapped at people with little or no provocation—I was not a pleasant person to be around.

Subbing helped me mellow out. As I was having success at it, I would recount my experiences to my mother and father at dinner, and I could see Dad reach for Mom’s hand under the table and squeeze her with excitement that I was getting on so well at being an educator.

See, my family has a long history with education. My father’s father, Reginald Mustain, was on the school board for fourteen years, many of which he served as president. My sisters Kristi and Kari both have degrees in Education and have had numerous teaching and coaching jobs since college. My younger brother Kirk has a provisional teaching certificate so he can teach full-time graphic design and computer science to middle and high school classes, and he has taught at the college level. On my mother’s side, her older brother Stephen Tegarden had a thirty-five-year career serving as principal and superintendent of schools all over the country.

One might say educating is in our blood. Even members of the family who do not teach are very invested in volunteering for the schools and sitting on boards.

So, when my father was squeezing my mother’s hand at dinner all those nights, it had to have been with the hope that I had finally found my calling. Teaching, after all, was something I could do and still continue to write in my free time—as a hobby.

Little did he know I was working on something. Little did he know how enraged I was becoming at the state of public education; that I felt compelled to write about it. I was running home all those nights after dinner to research all I could about the Columbine Massacre and put down my own tormented experiences.

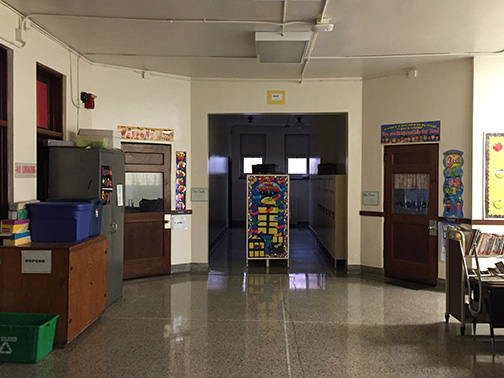

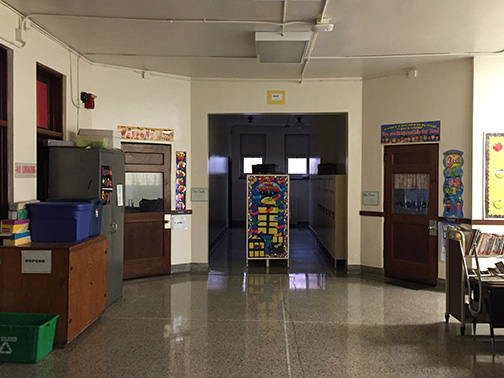

Marble floors and this unique locker nook between two large classrooms is just one of the many sights we all saw as kids that we probably took for granted, but looking back, provided us the most original schooling experience in the district.

Code-Switching

My favorite passages from “The Opposite of Suicide”:

We spend more time telling kids to stay away from drugs, alcohol, and smoking than we do teaching them how to identify the lower half of the periodic table of elements.

I realized I was gay by the age of twelve, but I tried to push it out of my thoughts. I felt guilty about it. Thought I could overcome it. I thought I was going to go to hell. Getting over that self-hatred is a process that takes several years. There is no doubt in my mind that has a long-term effect on a person’s psyche.

That last line is a notion I got from none other than N*Sync member Lance Bass. Bass came out publicly in 2006 after spending about a decade singing, dancing, and acting before the whole world. To keep something a secret not just from friends and family, but the entire world would be a hell of an undertaking. What’s especially messed up about it is we all knew Lance was gay from the beginning. So, why did he have to keep it a secret in the first place? Regardless, he did, and I heard him say once on his radio show that he is certain that being in the closet fucks up a person’s brain. So, I decided to drop that little chestnut in my essay.

Sidenote: I have never met a closet-case who wasn’t deeply emotionally disturbed. My out gay brothers and sisters will back me on this.

I recently watched The Way He Looks, a Portuguese film about two teen boys, one of whom is blind. The movie mostly follows the blind one, and the tension of the story is trying to discover if the new boy in town is gay. The movie had a happy ending, which gave me a weird feeling. I felt a little letdown that the new boy turned out to return the main characters’ affection. What a copout!

I’m accustomed to gay movies ending in the following ways: He’s willing to “experiment” a little, but he won’t take the plunge of acknowledging his love in public. Or they die in a suicide pact. Or they turn into terrible drunks and never achieve happiness. That’s how gay movies are supposed to end. Because that would have reflected my experience as a gay young adult.

As I was having this reaction, I stopped myself, and thought, What the fuck is wrong with me? Why was I bitter about these two boys finding love with one another? It’s because the environment I grew up in programmed me to expect the worst.

Where I live and work now, where I get my coffee, and the trains I ride with several million people every day, I don’t have to look over my shoulder anymore when I am looking at the profiles of other dudes on my iPhone. Funny how I felt more oppressed in a small city of 30,000 people, most of whom I knew very well, than I do in a city of 8 million strangers.

My voice has gotten lighter since I moved. Now, I wouldn’t say higher. My voice naturally has a deep register. But there’s just a little bit more of a softness to it. I’ve written about this phenomenon before. In particular, at the Pizza Hut I worked at in Iowa City, a fair amount of my coworkers were lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgendered. I noticed that all of the gay males who worked there, we all had this reflex to drop our voices an octave whenever we answered the phones. We had all learned this survival mechanism to, in uncertain company, put up these shields: change our mannerisms, how we talked, what we said, how we dressed. In linguistics this is known as “code-switching,” and everyone does it to some extent. But for many gay men, we are acutely aware of what about ourselves sets off homophobic reactions from other people.

So, when I worked at Pizza Hut I noticed that even over the phone, talking to faceless strangers, we were not willing to chance a homophobic interaction. I wonder who it was my coworkers pictured on the other side of the line. Their dads? One of their dads’s bigoted friends? Their preachers? What was going to happen? Someone calls their parents and says, “I called Pizza Hut the other night and Benji answered. You might want to have a talk with that boy.”

Who surprised me the most was Alonzo. He moved out of his parents’ house when he was 15, and ever since had lived primarily with other gay people who took him in. His life was full of the gay community; what the gay community has classically been for orphans like him. Alonzo was the most outrageously gay person I knew, and yet even he lowered his voice like the rest of us chumps whenever he answered the phone. That’s how deep it runs.

If you just take a behavior like that as a microcosm, then consider how many other things there are stacked up on top of that, how many ways people like me have to go about our daily lives because we are terrified, then you start to get a picture of how hard it truly is to be gay, and that it’s mostly because of how other people react to the way we naturally are.

Many people think there was a homophobic motivation behind my firing and that my illegal drug use from 16 years ago was scapegoating. I agree. Many people think I should sue. I disagree. Because I actually think the whole ordeal is fucking hilarious.

But honestly, I have to stop and think about this: While I was substitute teaching, pretty much every gay person I talked to about my job, asked: “How does being a teacher work out with being gay?” Which is pretty fucked up.

We’re engrained as a culture now to think that certain people are not eligible to be teachers. That’s how pervasive the fascism in public education is. And to boot, my gay brethren are keenly aware of where we are and are not wanted. For years I have noticed how many of my gay friends work in the fields of nursing and special education, especially in less populated parts of the country. Because trying to have a career doing anything else would be too hard a battle to forge, so many of us have settled for jobs within these industries that the ruling majority has deemed it acceptable for us to work in.

But I’ve noticed since moving to New York City I just don’t have that fear anymore. Living here I don’t have to watch what I say, how I sound, or how I look. I no longer have that closet surrounding me.

Life is so much better when you simply let people be themselves.

A major characteristic of the Prairie School architecture was creating open spaces within the structures. Things like this marble staircase and tall windows were just as iconic as the outside facade of the buildings.

Victims of Deferred Maintenance

My father worked on four referendums to save extracurricular sports and activities from being canceled by the school district. We won two of them. After he won the final referendum, he and his collaborators established the Galesburg Public Schools Foundation, a nonprofit organization with the sole purpose of raising funds for District 205 to acquire things it needed, but were not within its budget. Their first and most major achievement was building an auxiliary gym and pool for Galesburg High School.

That took six years of my parents, brothers, sisters, myself, and somewhere between fifty and one hundred committed citizens to see through to fruition.

After we turned the keys over to the district, everything was peachy, right?

My father answers, “Well, no . . .”

Right away there was a humidity problem. The facility had a built-in state-of-the-art dehumidifying system, but the maintenance worker the district hired didn’t know how to run it. Several of the people who had overseen the construction urged the district to pay for a maintenance person to be trained how to run the dehumidifying system and be kept on staff.

A few years after the gym and pool were built, the district had to make cutbacks again. One of those cutbacks was they let go the one employee who knew how to run the dehumidifying system. They didn’t hire anyone to replace him, nor did they pay to have someone else trained. Now there’s rust on the beams and mold throughout the building. It’s going to cost at least $900,000 to fix the damage, which is three-quarters what the community raised to build it. The facility is only twenty years old.

“I know if they hired people who knew how to operate the system, they wouldn’t have a problem,” my father says, adding, “That’s just the way they do things.”

At some point after the gym and pool were finished, my father fell out of high opinion with the school board. I’ve heard it said a number of times this was because of jealousy—the powers that be felt insulted that my father’s organization could do things the district was incapable of doing itself. In regards to all the work, their reaction was “Thanks, but no thanks.” And, in retrospect, their naming the pool after him was a backhanded compliment. Dad can’t swim a front crawl to save his life. None of his children have ever participated in swimming as a sport. I, however, decided that because I would be the first person in my family to go through GHS after it was built, I signed up for swimming classes and swam in Douglas D. Mustain Pool nearly every day of the three-and-a-half-years I attended high school.

So, when it comes to ideological arguments about why the district should preserve Silas Willard, the board has no interest in hearing my father out. In fact, they may be adamant to tear it down because it’s him who’s fighting against it. To add insult to injury, the gym he raised $1.2 million to build for them is being sent down the same path of neglectful management as the Silas Willard Schoolhouse.

My dad can get a building built but does not have the power to save one from being torn down.

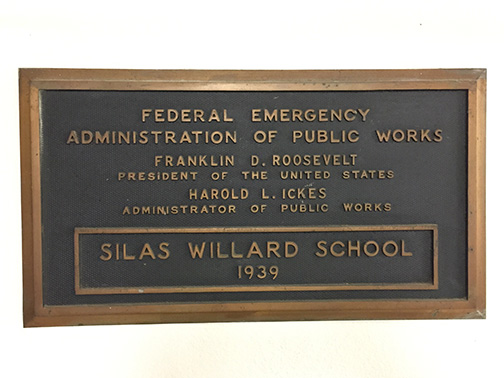

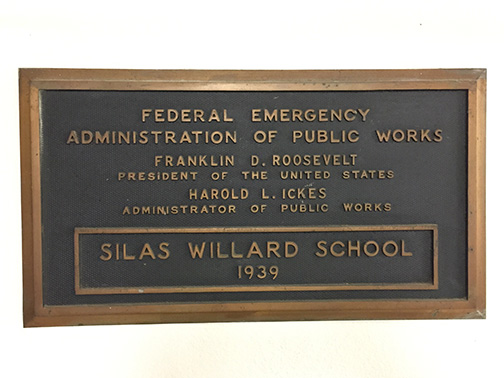

Originally built in 1912, Silas Willard Schoolhouse was added onto nearly thirty years later, giving it new life. This was commissioned by the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works, headed by Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the Great Depression; perhaps the single most socialist thing an American President as ever undertaken, but, hey, people needed work! Some might say we need something similar to be done for our crumbling infrastructure and public buildings these days.

The “No” People

I’ve always found it deeply ironic that Carl Sandburg grew up in Galesburg. Not only was he one of the most famous writers of the twentieth century, he was equally known for his activism. Before he even became famous as a poet, he toured the country lecturing on Walt Whitman and socialism, tying the two together because he found Whitman’s writings to be inline with the tenets of socialism.

The Galesburg Sandburg grew up in was not much different than the one I grew up in. It was a deeply conservative community, even a hundred years ago. His father, August, was a blacksmith for the CB&Q Railroad. Illiterate, August was a staunch Republican. Carl knew from a very young age that he himself was a leftist. He and his father fought over the fact that August continually voted against his best wishes—August worked very long hours for very little pay. Carl could never get through to him that if you were working class and voted Republican, you were voting for the very same people who were exploiting you.

By today’s standards, while the people who vote Republican are not illiterate—but certainly there are still those among us who have never learned to read or write—but many people are brought up in our schools as non-literary. People who were not taught how to read properly, people who are poor at recognizing nuance, to grasp subtlety and lyricism. People who read everything at face-value and cannot recognize when they are being fucked with.

We should actually be quite alarmed by how many people referred to “The Opposite of Suicide” as an article. That in itself shows there are so many people these days who are literate only in the most rudimentary sense. I mean, even the man who fired me referred to it as an article, and he was superintendent of an affluent school district.

This is a short biography of Carl Sandburg in a textbook. One of the main things textbooks keep hitting in 6–12 literature is an author’s word choice. In the field of Rhetoric, the way an author phrases things is how she conveys her ideas, but it can also be the way she covers-up or omits certain ideas, certain facts that she and the people holding the purse strings don’t want the reader to know, that are better left unsaid.

Now, given that this bio is so, so short, I would not expect the writer to go too in depth, but let’s take a look at it:

Carl Sandburg (1878–1967) was a Pulitzer

Prize-winning American poet, historian, and

novelist. Born in Galesburg, Illinois, to

Swedish immigrant parents, Sandburg

decided at age six that he would be a writer.

Although, he had to quit school after eighth

grade to go to work to help support his

family, Sandburg continued to write. As he

pursued writing, Sandburg worked in a variety

of trades from factory worker to

newspaperman. He also became a well-known

musician and political activist. The

variety of Sandburg’s experiences informed

his writing, and Sandburg eventually gained

recognition as an iconic American writer.

This is all true. Sandburg did drop out of school when he was only thirteen. But this short bio, given to young, susceptible minds, makes it sound like he did it because his family was poor and he had to support them. That is only part of why. The main reason was most people didn’t go to high school back then. Back then young people had the legal right to choose not to attend high school. It cost more money to go to high school.

I wouldn’t expect a 50-word biography to go into this, nor would I expect the person who wrote it to know this information, unless they had done extensive research on Sandburg, but the family did pay for his older sister to attend high school. She passed her schoolbooks down to him and he used them to teach himself. That was a way for the family to cut corners: they sent the older one to high school, but Carl was equally educated, maybe even more so because he was learning at his own pace, within his own parameters. This may even speak to why he became so knowledgeable, so talented, and such a radical leftist. Because he was self-taught, there was no one pulling strings on young Sandburg. He did have mentors in the community, but he sought them out on his own.

The line “political activist” sidesteps the fact that he was an activist for socialism. Of course the bio is not going to mention that because textbooks intentionally avoid any language that could be construed as having polemic. Although if you read enough textbooks, you’ll see that they are intrinsically conservative. Actually, whenever the content from a selection is obviously left-wing, like the Civil Rights Movement, or Immigration, they tiptoe their way through these topics. I think it can safely be said most novelists, poets, and playwrights throughout history have leaned to the left—at least the good ones. But a textbook won’t call out a writer’s political beliefs, even if they are embedded in just about every single word he ever laid on a page, because the textbook is a product, and at the end of the day, that product has to be marketable to school districts who are known for being conservative.

The distillation of rhetoric is how misinformation spreads and breeds non-literary minds—Like students seeing a black and white photo of me on Facebook next to the word “Suicide” and assuming the worst, without having the inclination to read on.

Carl Sandburg left Galesburg at the age of nineteen. He knew it was time to leave when he became suicidal. Yes, young, mythic Carl Sandburg contemplated throwing himself in front of a train—which also happens to be how an absurd number of people die in Galesburg. Mostly because it’s a very effective way to do it, and as Sandburg thought himself, people might mistake it for an accident.

Sandburg instead reminded himself there was a great big world out there, so he decided to go see it. He left. And never came back, really. He saw Chicago. He rode the rails all over the country. He became enamored with getting to know strangers, wherever he could find them. This intensified his belief in socialism and the common good of the American People—not the ‘Murican People.

He ended up in Wisconsin, where at the time the Socialist Democratic Party was making major breakthroughs. Socialists from around the country were migrating there. The world was paying attention to the very groovy stuff that was going on in Wisconsin. Carl wanted to be part of it. And so he became a big part of it.

Galesburg’s favorite son, Carl Sandburg, who produced some of the most widely-read poetry of the twentieth century, who won the Pulitzer Prize three times, who left the world with everlasting gifts of his testaments to the common good of the masses and the evils of the rich, once upon a time wanted to commit suicide—Then he changed his mind and went and did the opposite.

Silas Willard Schoolhouse is set for demolition next summer. It would appear many of the people who would have fought for its standing have moved away.

#savesilas

BIO

Kyle Mustain received his BA from the University of Iowa, and MFA from University of North Carolina Wilmington. His work has appeared in St. Sebastian Review, Medium, and the Writing Disorder. He balls every day.

Kyle Mustain received his BA from the University of Iowa, and MFA from University of North Carolina Wilmington. His work has appeared in St. Sebastian Review, Medium, and the Writing Disorder. He balls every day.

Kyle Mustain received his BA from the University of Iowa, and MFA from University of North Carolina Wilmington. His work has appeared in St. Sebastian Review, Medium, and the Writing Disorder. He balls every day.

Kyle Mustain received his BA from the University of Iowa, and MFA from University of North Carolina Wilmington. His work has appeared in St. Sebastian Review, Medium, and the Writing Disorder. He balls every day.