The Opposite of Suicide

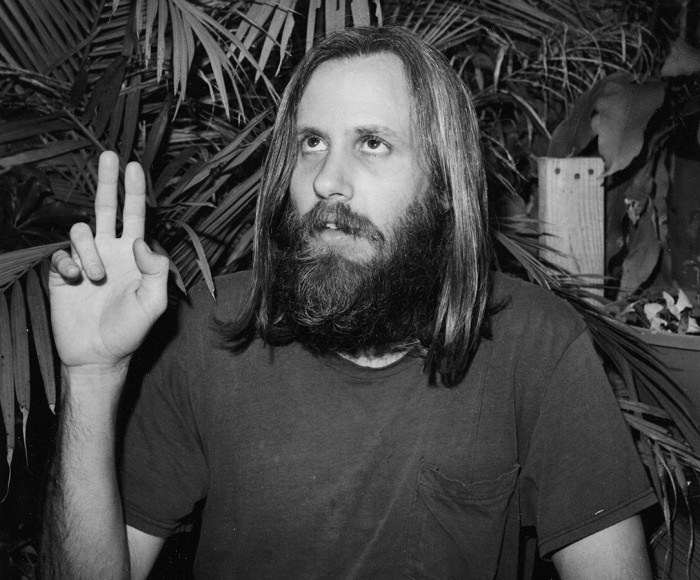

By Kyle Mustain

y first day as a substitute was six weeks after the second worst mass shooting by a single person in US history. This one took place in a school building, as many of them do anymore. There was a point during my second block, just after I had sent the students to work on their news-gathering quizzes in the computer lab—a secluded room off a small hidden hallway on the second floor of the building—when I asked myself, What would I do if there was a shooter?

y first day as a substitute was six weeks after the second worst mass shooting by a single person in US history. This one took place in a school building, as many of them do anymore. There was a point during my second block, just after I had sent the students to work on their news-gathering quizzes in the computer lab—a secluded room off a small hidden hallway on the second floor of the building—when I asked myself, What would I do if there was a shooter?

I looked around the room, which had not changed much at all since I had gone to school here fifteen years ago. There was still a tube television hanging in the corner, a relic from when Channel One donated TVs to all of our public schools in the early 90s. The computers are all connected to the Internet, something perhaps less than a dozen computers in the school could do when I went here.

In this computer lab and the traditional classroom adjoining it, there seemed no obvious way to protect ourselves. We’d have to come up with something clever, like barricading the desks against the door, which swung out, not in, but the desks could block the shooter or shooters from entering the room, I guess. We’d have to hide along the walls, out of visibility from the door. But if the shooter came in from the door on the computer lab side, we’d be sitting ducks.

Maybe we could devise a way to climb down to the courtyard. The cord from the air conditioner—would it hold? It doesn’t seem too far a drop. We would have to risk broken legs just to get down to the courtyard, where the doors are locked, but made of glass. We’d have to break through them, then run out the front entrance to safety.

But how would I know it was safe on the first floor? There could be several intruders in the building, some of whom could be stationed at the front door to prevent us from escaping. Or the front entrance could be booby trapped. I wouldn’t know anything in that situation. I wouldn’t know what to do besides wait and hope the shooters don’t come into our room.

What if they did? I ask myself if I would stand in front of a gun for these young people.

* * *

The problem was the scenario I was running through in my head was the one I’ve played out hundreds of times: two shooters, running through the hallways, tossing homemade bombs, firing sawed-off shotguns. I was eighteen when Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold went to their high school one Tuesday morning and proceeded to kill twelve of their classmates, one teacher, and injured twenty-four others.

The Columbine massacre was the first mass shooting of its kind. Not the first school shooting, by any means. Those happened quite frequently in the late nineties. But Harris and Klebold’s massacre was the first to play out over live TV. In real time. It happened on April 20th, which just so happens to be a pot-smoking holiday. Eric and Dylan’s attack on their high school and 4/20 was purely coincidental. So is the fact that Hitler’s birthday is April 20th. None of these things had anything to do with the other.

Harris was the brains behind the operation. He had been planning the massacre for eighteen months. It was supposed to happen on April 19th, the Monday after Prom. Eric and Dylan had to wait one extra day, though, for their friend to come through with one more box of bullets, and perhaps they also, understandably, had a case of cold feet. If the massacre had occurred on April 19th instead of April 20th, there would be no inclination of the media to speculate it had some cryptic link to Nazism or Weed.

Eric picked the date of April 19th, 1999 because it was the fourth anniversary of the largest domestic terrorist bombing in US history at the Alfred P Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City. The Columbine massacre was never meant to be a school shooting. Eric and Dylan were equipped with guns just in case they had to shoot people, but their intention had always been to blow up the building. They wanted to outdo the Oklahoma City bombing, which killed 168 people. They hoped the bombs inside Columbine would kill hundreds more.

* * *

After my first day as a sub I learned to relax. My teaching style, or “subbing” style, more accurately, is laid back. I moved back to my hometown during my last semester of grad school, and started doing this because the school district was hurting for subs. I never thought I would go into teaching, in fact I had terrible anxiety about it, but not seeing how else I was going to make a living, I registered. All that registering requires is a college degree, a $149 fee, and a background check. Criminal background check. They did not check my school records.

Just after that first day, I somehow came to be known as the “cool sub.” Probably because I’m young. Although I don’t consider 32 that young. It’s probably more because I act young. But I wonder if maybe it has something to do with my experience in high school.

I was outed when I was seventeen. I had only told a handful of friends and my immediate family about my sexuality, but after a few months, that little bubble of people could no longer contain such a large secret. My best friend told his other best friend, and then he told a group of guys who decided to use it to hurt me. They showed up to school early one day, approached several gossipy girls, and enlisted them to spread the word around school that my friend Chadand I were gay for each other. I knew about this ahead of time because they phoned me the night before to inform me “the whole school” was about to find out about me.

I don’t remember that day very clearly, as I’m sure no one under such duress would choose to hold on to such an experience. The only details I can recall are that by second period I started noticing people looking at me differently. By third period people who I usually said “Hey” to every day looked away from me. That much was to be expected, I guess. But what really took me by surprise was how the faculty reacted, which was exactly the same as the students—whispers and funny looks. From that day forward I was not taken seriously as a student anymore. That was how the remainder of my high school experience played out. This whole school turned its back on me.

I started skipping school. I got high all the time. I got in fights. I got suspended. I called a teacher a bitch to her face. I quit all my extracurricular activities.My grades didn’t just slump, they plummeted. After the first time I was arrested, the rest of my teachers were pretty much done with me. I became a pariah. My friends’ parents didn’t want them hanging out with me. I graduated early my senior year.

The thing is, I wasn’t alone. My class held the record for the most studentsto graduate at midterm from my high school. The school district responded the next year by changing the requirements for graduation, rendering it harder for students to graduate early, because it looked bad that so many of us wanted out of school. They did this instead of asking themselves why we fled.

My teenage years were a lot of seriously undue stress and bullshit. They really didn’t have to be. I was so disaffected by mine, I was on antidepressants from the age of 16 to 25. The other day I had to yell at a class to be quiet after the bell rang, and it dawned on me that ten years ago I would have been so numb from meds, raising my voice like that would have been a herculean effort for me. What I’m getting at is it took me years to become an adult. I spent the first half of my twenties getting over shit that happened to me in high school. It doesn’t have to be this way.

* * *

The next time I subbed at the high school was two days after one of the senior class members got in his car under the influence of drugs and alcohol at eight-thirty in the morning on a Sunday and drove his car kamikaze-style down one of the busiest streets in town. Witnesses said he had to have been going over a hundred miles per hour by the point he lost control, ran off the road into a vacant parking lot, hit an embankment, went airborne, rolled and was ejected from the vehicle. He was declared dead four hours later at a nearby hospital.

Everyone was calling it a suicide. It had to have been. But why so close to graduation?

That was only my second time subbing at the high school, and it was for the same teacher. The first thing I did when I got in that morning was check to see if the young man who died had been in any of the classes I had subbed for. He hadn’t been, but the teacher had circled the photos of the students on the class roster who had been friends with him and left instructions that they had each taken the past couple days off school, that they were to be excused if they asked to go to the nurse, no questions asked. I noted to myself how they all kind of looked like him. Long hair, jaded. I mean jaded to the point it is humorous how unmistakable it is.

Who’s taking care of these kids?

* * *

Eric and Dylan went into the building with their guns only after the large bombs they’d planted in the cafeteria didn’t detonate. Ideally the explosions would have caused the commons area over the cafeteria to collapse, burying the inhabitants inside. The bombs were supposed to cause structural damage and start fires throughout the building, killing hundreds within minutes. Eric and Dylan were going to perch themselves outside with their guns, and pick people off one by one as they tried to reach safety outside of the burning building.

Reading about Eric and Dylan, I see a lot of similarities between them and some guys I grew up with, who beginning in middle school started becoming outcasts. By the time we were in high school these guys and other guys and girls like them came together and they all gradually got into punk rock, thrash metal, death metal, hardcore hip-hop, hardcore techno, industrial, etc. Although these sub-genres of rock have their rivalries, they share the core emotion, which is anger; deep-seated anger that seeks to expose the injustices and hypocrisies of the system within which we live. That kind of cynicism is something that comes about once a person has been thrust outside the status quo.

This group of guys I knew started wearing black leather jackets. They decided since they were social outcasts, then their clothes had to be in open defiance of what our classmates wore.

In retrospect I realize they were part of the popular clique in the beginning of middle school, but as time progressed and cliques began to solidify, these guys were phased out of the clique. They used to get invited to all the popular parties, sit with us at sporting events, but then something just happened. A turn came about in middle school when these guys were no longer invited to things, and it totally wasn’t by their own volition. It was the popular kids deciding to not ask them around anymore. I think it was because they were considered not as good-looking, and a little too awkward around members of the opposite sex. Their tastes in movies, music, and popular culture were not as “advanced.” They were still into comic books and toys when other guys were making the shift to popular music, gold necklaces, and cologne. These guys got left behind. That scorn manifested into rage.

They acted out violently, but it was subdued. They started drinking at a younger age than everybody else, and drank more often. They mostly hung around each other, didn’t have much interest in traditional courtship rituals such as “going steady,” “Homecoming,” and “date rape.” They were just punks. A typical Friday night for them would have been a shared bottle of cheap vodka and some petty vandalism. Telling the world to go fuck itself.

That’s how Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold and their group of friends were. That’s how they were treated by their peers, and that’s how they came to be that way. I see that all the time. I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad thing. People who go through that kind of ostracism from their peers, while they do suffer severe angst, it builds them into the people they will become. Many of these outsiders will use that pain to branch out from their peers. We need the radicals. We just need a better way of showing them they have a function in society. By we, I mean teachers. We must not make enemies of our outsider students.

* * *

At the beginning of the new school year, a teacher requested for me to be his substitute for a week while he went out of state for his daughter to have a lifesaving surgery. I had by this point gained a glowing reputation with both students and teachers alike. It meant a lot to me that he thought to ask me to take over for him during such a sensitive time for his family. It was a weeklong subbing job, and I decided I was going to really devote myself to being an almost-full-time teacher.

Before the morning bell on the second day of the job, a student came into my classroom and asked me if I found his shirt offensive. It was brown-orange—the color of a basketball—and said in black letters: BALL EVERY DAY. A Nike Swoosh hung at the end of the sentence like a punctuation mark.

I thought it over. Testicle every day? I asked him in a protective way, “Are people calling you gay?”

He answered, “No.” He clearly didn’t see how the shirt was offensive, either.

“Then I don’t see anything wrong with it,” I told him.

Then he told me it was a teacher, not a student who was offended by the shirt. She told him to turn it inside-out. He asked me if he had to. I told him as long as he was in my class he didn’t have to. Then I rolled up my sleeves and told him an anecdote about the same thing happening to me when I was his age. I had worn a shirt that said WHAT THE HELL YOU LOOKING AT? to school several times, without bothering anyone. Most teachers didn’t even notice it. Some even thought it was funny. But all it took was one teacher who disagreed with the word “hell” and I wasn’t allowed to wear it to school anymore.

“So just lay low for the rest of the day,” I told him, “Make sure that specific teacher doesn’t see you again.” We had a laugh about it. I felt like we had established a bond.

As the first warning bell was sounding, the door at the back of the classroom swung open. The teacher from the next room was standing in the storage area that connected our classrooms. She’s a middle-aged woman I had found very accommodating over the past two days of the job. We’d even palled around a little between classes. She waved me over.

When I got to the back of the room, she leaned over and whispered, “Your student Diego is wearing a shirt that has a double entendre on it.” She sounded like she felt smart for using the term double entendre, like we were using some kind of secret adult code.

“Yeah, I saw, it,” I answered, “BALL EVERY DAY?”

“Yes!” she inflected outrage through her whisper-voice, and looked at me like I was supposed to feel outraged too.

“I’m sorry, but I don’t see it,” I told her.

She assured me, “It’s a double entendre. You’ve got to make him turn it inside-out.”

I couldn’t help making an annoyed face, because this was truly annoying. I knew she was wrong. But I nodded and said, “Okay.” I sent the poor guy to his counselor because it’s my job. I don’t have the authority to go up against an actual teacher.

A minute later I was suffering through the “Moment of Silence” and “Pledge of Allegiance.” Anyone with eyes and ears can scan a classroom and tell who is into it and who is not. The girl with the blond ponytail and the shirt with 1 JOHN 4:14 looks severely into “The Moment of Silence,” belts out “The Pledge.” The boy with the dark circles under his eyes and the CALL OF DUTY: BLACK OPS hoodie puts his head down reluctantly during “The Moment,” yawns through “The Pledge.”

Sometimes I look down during “The Moment,” out of respect for whatever it is I’m supposed to be paying respect to. Other times I walk silently about the room, handing out papers. I’m not in any violation. “The Moment of Silence” is not mandatory. I usually do “The Pledge,” although I don’t know why. Partly to check if I still have it memorized after all these years, but also because I like to analyze how aesthetically unappealing of poem it is—Is it even a poem? “The Pledge,” in its staccato cadence has a braiwashy vibe to it I didn’t catch onto when I was younger. Forcing people to say it every day sounds like something out of a Hitler Youth manual. Even if we don’t have to say it, the words get into our brains like a bad pop song.

I don’t remember having to say “The Pledge” after the fourth or fifth grade. There seems to have been a resurgence of interest in it after the turn of the century. There was no such thing as a daily “Moment of Silence” when I was student, either. These poor young people. I had it so much better than them.

All these two rituals do is create two minutes of awkwardness for the two thousand people standing in the school, parsing us into our ideological groups before we even have a chance to begin what should be the impartial process of education. They only take about two minutes, but these are the two minutes that start off our day.

I scanned the shirts people were wearing: Duck Dynasty, Sons of Anarchy, Monster Energy Drink, DRIVEN TO WIN, AINT NOBODY GOT TIME FOR THAT, SWAG OVER EVERYTHING. One girl was wearing a memorial t-shirt for the student who committed suicide the previous spring. The shirt of the boy next to her said NO TURNING BACK. Another had a drawing of a dog with a musical note coming out of its behind. The musical note was upside-down.

I located The School District’s Dress Code hangingon the wall behind me. It is posted in every classroom. And it’s vague. I’m guessing intentionally so. What constitutes pajamas? There was a girl right in front of me wearing a teal hoodie and gray sweatpants, which are essentially what I wear to bed in the winter. Should I bust her for looking like a slob? Why would someone do such a thing to someone else? To exert my power over her? Be an asshole just because I can?

The boy who had the BALL EVERY DAY shirt came back in with a shirt that had the high school mascot on it. It was creased like it just came out of a package. I gave him a sympathetic look. Oddly enough, just fifteen minutes before the incident, Diego and I had bumped into each other on the way to school. He had yelled out to me, “Hey, Mr. Mustain!” as he was crossing the street adjacent to me. We biked together for half a block. He asked what we were doing in class that day. “Just watching a movie,” I said, then apologized that I had to speed ahead because I was running late.

He seemed like a cool enough kid. I’m guessing his shirt meant he likes to play basketball every day because he enjoys it, even though he isn’t good enough to play on the school team. Plus he bikes to school. Hardly anyone does anymore. I’ve never seen more than ten bikes on the rack in front of the school. Ten people out of two thousand bike to school. Diego isn’t lazy.

I was pulling the TV cart away from the wall and putting the MythBusters DVD into the player when the vice principal showed up outside my door. I feigned a smile at her, and gave a, “What can I do for you, Ms. Fra—,” then corrected myself, “Mrs. Bennedetti.” I almost always call her by her maiden name, the name she went by when I was in school here.

She waved me over without making a sound. That’s a surefire way to clue everyone in on the fact that she has something to say to me that the students aren’t allowed to hear.

“I just received an e-mail from Mrs. Frega telling me that one of your students was wearing a T-shirt that has a double entendre on it.”

FUCK MY LIFE

“Uh-huh.”

“Did you make him turn it inside-out?”

“He asked to go to his guidance counselor. When he came back he was wearing a different t-shirt.”

“Okay, great! Thanks for helping out!” She always tells me, “Thanks for helping out!” whenever she sees me. It makes me feel like I don’t actually work here.

She came from the office, in the front of the school, to the science hall, which is in the back of the building, just to make sure I, the substitute, was following orders.

After Vice Principal Bennedetti left, I turned on the Mythbusters DVD, and headed to the back of the room with my coffee thermos and notebook. I started recording everything that had just transpired because I was fuming pissed. I put two things together from Mrs. Bennedetti’s visit to my classroom. Number one, Mrs. Frega must have e-mailed her with concern that I was not being compliant. Number two was that Mrs. Bennedetti might have come to dig up old grudges with me.

I sat in the back of the room so the students couldn’t see how tense I was. I was holding myself back from overturning the table, screaming, maybe even bursting into tears. Instead I sat and stewed and couldn’t help but stare at the back of a young girl’s bright orange t-shirt saying to me: WHAT KIND OF A PERSON ARE YOU?

* * *

Eric Harris was a psychopathic murderer with a god-complex. Dylan Klebold was a depressive who sometimes lashed out violently. Eric was a charismatic manipulator who told people exactly what they wanted to hear. Dylan wanted to be noticed. He wanted to fall in love, got his heart broken over and over again. Eric wanted to fuck girls. Eric hated everyone, probably even Dylan. Dylan planned to commit suicide. Eric wanted to annihilate mankind. Dylan had brown hair. Eric was blond. Dylan was good at a lot of things, among them writing stories. Eric was a genius.

I was a depressive. I laid in bed for hours at a time listening to sad songs on repeat. I was addicted to sadness. All I wanted was for someone to understand me. Every time I reached out to someone I thought maybe did, it ended in more disappointment. I realized I was gay by the age of twelve, but I tried to push it out of my thoughts. I felt guilty about it. Thought I could overcome it. I thought I was going to go to hell. Getting over that self-hatred is a process that takes several years. There is no doubt in my mind that has a long-term effect on a person’s psyche.

The night after the whole world found out I was gay I went up to my room, turned off the lights, unplugged my alarm clock and VCR to make the room the darkest it could get. I laid under the covers, crying in cold sweat. I wanted to kill myself. But that wasn’t really anything new. I had been having that fight with myself off and on since the age of twelve, and I’d gotten quite good at talking myself out of it. Although this time the pressure was more extreme, more public. I guess it would have made a statement if I killed myself, but that felt too much like what people would have expected from me. Like, oh god, the guys who outed me would have to live the rest of their lives with that terrible thing hanging over their heads. But who would be the real loser in that situation? Me! I still wanted to fucking live, damn it! That would have sucked for my family too, but really at that moment I was probably thinking my family could go fuck themselves, too. All that mattered was what was going on in my life, at that very moment, and how I was going to get out of it alive.

I probably spent at least an hour fantasizing about taking guns to school. My dad has several. I knew where he hid them and where he kept the bullets. That would have been really fucking easy. In fact, it would be so fucking easy to shoot up a school it’s a fucking joke. I laid there going over the fantasy in my head, playing it over and over in different scenarios. Which door should I go in? Which hallway would I see the most people I hated? Was I going to kill just Nate and Scott, or should I go all-out and try to take out as many people as I could? I would have to—just have to—take out the administrators. Otherwise what would be the point?

Every time I went over it, it got more and more complicated. There was no way it would have transpired as good as the way it worked in my dark little day dreams. I knew how that all worked out, the fantasizing of things. The two times I’d had sex were revolting, awkward affairs, nowhere near as good as the hundreds of suave, silky scenarios I’d been masturbating to for the better part of a decade. The two times I’d had sex were so bad I never thought back to them, pushed them far into the deep catacombs of my mind. I understood that fantasies are idealized realities. Perfection is a fantasy. That’s what makes fantasies so special over reality: we can perfect them, easily. Reality takes hard work if you want to realize your fantasies, or at least come close.

In bed that night I understood shooting up the school was going to take a lot of hard work and planning. I’d have to learn to use a gun, build bombs, rehearse, and get my body in shape and shit. I’d have to enlist some friends to help out, and all that seduction over to the dark side shit would have taken a lot of mental preparation. It was a long term solution for a short term problem.

As I was still lying in the pitch dark of my room, I forced myself to start thinking more positively. There had to be a better way out of this; a way to knock those bastards on their asses and dispel the rumor about me. It’s hard to explain sparks of inspiration, where they come from. I think lying there in bed and going through all the bloody scenarios, the really dark shit, was necessary for me to gradually climb up out of and find the positive solution.

As the plan started to come together in my mind, I sat up in bed, after what was probably two hours of sulking. I switched on the lights, plugged my appliances back in, and got to work.

* * *

Nearing the end of the first block it dawned on me what the boldest, most fitting course of action should be: I should ask Diego if I can buy the BALL EVERY DAY shirt from him.

Do I put it on right then? No, I better take it home and wash it. Wear it tomorrow? No, I have two more days on this subbing job. I need this whole paycheck. Friday. I’ll put it on just before first block begins. The students will love it. By second block they’ll spread it around. “Mr. Mustain is wearing a t-shirt that a teacher told a student he couldn’t wear!” How fast will the teachers start reporting me? Will the principal come during second or third block, or will I make it all the way to fourth? Will he pull me out of class and replace me with a faculty member or an administrator? Will they bring the police? Will I be led out of school in handcuffs?

I don’t put anything past them.

There will be an article in the newspaper. Reporters will call me for a statement. Will it go beyond the town? National news? Bill O’Reilly? Rachel Maddow?

Before anything like that happens, I’ll have to deal with the town. Immediate firing. That I can count on. But then there would be the public shunning. I’ll probably have to cancel my membership to the YMCA after all the scornful looks and fathomable vandalism to the things in my locker. I know those gestures won’t hurt me or bother me as much as the looks of sympathy I’d get from other people; people who agree with me, but don’t want to stand by me; not what I did.

I can’t do it. I need this job too badly.

I resign to push it down. Think of the money. Pick your battles. Forget about it and think about the lesson plans for the next two days. I’ll look for another job. Maybe this frustration is a sign it’s time to move on. Maybe I’m not cut out for this.

The back of that girl’s fucking shirt keeps asking me:

WHAT KIND OF A PERSON ARE YOU?

* * *

All three of us were journal writers. Eric called his “The Book of God.” Dylan titled each of his entries individually, and were structured like mine: name, date and title in the righthand margin, then title again, centered above the text. I titled mine, “Final Thoughts,” a morbid joke that they all would add up to one epic suicide note.

I want to say we just wrote about the same themes, that I didn’t go to the extreme Eric did, but the thing is I explored my dark side thoroughly. So did a lot of my friends. In fact I’m willing to bet most adolescent boys have secret projects. One student showed me YouTube videos of some BMX ramps he and his friends built. That reminded me of when my younger brother and his friends made improvised horror films and one summer even built a wrestling ring complete with ropes in our parents’ backyard. Some of my friends in high school found a bunch of dead squirrels and made a funny video of a hand puppet beating them up. They would show it at parties. Those are all ways we burned off some innate hunger for violence. Sure some of them were unsettling, but they were within the bounds of reason.

Eric was really into the German hardcore techno band KMFDM[1]. Eric and Dylan may have listened to Marilyn Manson, but his music had nowhere near the influence over them that the media made it out to be. That gives Marilyn Manson way too much credit. Come on. Eric and Dylan were too smart to buy into that.

I’ve been listening to the early KMFDM albums Eric and Dylan would have listened to. The lyrics seem very pointed. If I had to hazard a guess, the lyrics of their first album must be directed at a handful of specific individuals. The same as Eric or Dylan’s journals would have been. The same as most people’s journals are at that age. When a person writes a love poem, it is generally towards one person, right? We’ve all had unrequited love, right? So when one writes rage poems, they must be no different. They are probably very often towards a specific target. Can we call it unrequited rage? How about unfulfillable rage? Somebody you never got to kill or do some kind of terrible harm to, whether physical or psychological. I don’t see this as being indicative of psychopathic behavior. I think it’s venting. It’s channeling rage into creative energy. It’s sublimation. Isn’t this is why we create art;to feel like we have obtained things which are unobtainable?

Because I am a writer, I wrote. Because I am a depressive, I didn’t share my stories. But I wanted the world to end, thought everyone needed to die so I could start humanity over again, my way. I just never took it to the next level. I wanted to kill people, but I have never killed anyone. I never even got as far as plotting a murder. I grew out of it. It wore off. Somehow. But what I can’t help wondering about, sifting through all the information I can gather about Dylan and Eric, is what series of events could have possibly led to me deciding to make my fantasy a reality? What would have pushed me over to fully functioning homicidal artist?

* * *

In the hall the other day a young man walked by me, mimed like he was holding a shotgun, took aim at me through his sites, then threw his shoulders back from the imaginary gun’s blowback. His lips puckered, let out a “poof.” This is not even a student who I’ve had to discipline. This is one of the ones I get along with.

Some students joked about finding their Math teacher’s house and toilet papering it. He joked back, “If you do find my house, let me warn you, I do support the Second Amendment.” He more or less told a group of 14 year-olds that he would shoot them if they came on his property and threatened to ruin his Saturday.

The school secretary and Bennedetti were excited, describing the reconstruction of the high school in the next town over. These two were gawking out, jaws agape, eyes wide. I asked what the big deal was. The secretary answered, “All of the hallways are going to be curved.”

“Well that sounds pretty fancy,” I said, expecting this to be a discussion of the artistry of interior design.

The secretary added, “It’s so the shooters won’t have a straight shot at anyone.”

I looked puzzled.

“So when people are running from them, they will be going along the curve instead of straight. They’ll keep turning and it will be harder for the shooters to aim.”

Martin Luther King, Jr. Day wasted 5-10 minutes of every class in the entire school district. It came off as a shameless PR ploy by the School Board in the weeks following the George Zimmerman verdict to proclaim: “We’re not racists.” The school board is composed of middle-aged, upper middle-class white people.

We spend more time telling kids to stay away from drugs, alcohol, and smoking than we do teaching them how to identify the lower half of the periodic table of elements.

When teaching a shop class a student asked me in front of the entire class what kind of cigarettes I smoke. I made a snap judgement, decided that I admired his boldness, and gave him an answer. Then I asked him which brand he smoked, and everyone in the class announced which brands they liked. We discussed the qualities of all the different brands. I urged them if they had the extra money, to get American Spirits because they lacked the harmful additives other tobacco companies put into their cigarettes, but I understand how expensive they are. The rest of that block went smoothly. I won them over by not pretending to be something I’m not, something above them. They respected me for my candor.

I noticed a boy texting one day. He asked what my cellphone policy was. The school’s cellphone policy is gestapo-esque. Something like I’m supposed to seize it from him. Second offense is automatic suspension. Each teacher has her own policy, though. We had just taken a test and had literally nothing to do to fill up the rest of class time, so I really didn’t care. Why not let them play around? Why jump to the assumption they’re doing something sinister with them? I’ve seen just as many students reading the news on their phones or exploring Reddit as I have playing video games. I have never caught a student watching porn.

Then he said to me, “I’m actually texting my mom.” That seemed unexpected, but it was better than his buddy waiting outside with the artillery.

What was he texting his mom about? That morning on his drive to school he thought he saw his friend out of the corner of his eye, sitting in the shotgun seat next to him. He had been friends with the boy who killed himself last spring.

He had hesitated telling me, but for some reason decided I was someone he could tell this to. He had hair down to his neck, black baggy jeans with a chain wallet, and the emblem of some alien-themed band on his charcoal shirt. He told me he sees his friend all the time and it freaks him out. “What does it mean?” he asked me.

I told him, “Just the other day, I thought of something really funny that my good friend and I used to say. An inside joke we had, right? Well, I pulled my phone out of my pocket, and I was just about to text him when I realized I don’t even have him in my contacts. He committed suicide twelve years ago. He died before there even was such a thing as text messaging, and yet the other day I tried to send him a text. I guess what I’m saying, man, is it never really goes away.” I gave him the best possible answer I could give him, which was the one that was not fully thought out.

I haven’t talked to him since that day, but I see him in the halls every now and then. He usually looks pretty happy. A young person’s mood can switch on and off like a light bulb, though. I remember that. I have no way of knowing if what I said that day helped him. I just wait for moments like that to happen.

* * *

Brooks Brown was Dylan Klebold’s best friend until Eric Harris moved to Columbine in middle school. For a while they were a threesome, but Eric didn’t like Brooks, and a tug-of-war was waged over Dylan. Brooks remained on-again, off-again friends with the pair in the intervening years, but it was clear Eric had won Dylan.

After the massacre, Brooks was contacted by a young journalist named Rob Merritt, who felt empathetic to Brooks’ plight to get his story out about Eric and Dylan. Three years after the attack they published a book about Columbine from his point of view. It’s a fascinating dynamic these two have. Merritt is four or five years older than Brooks, Eric and Dylan, so he was not far removed from the experience of high school when the attack occurred. And he seems to have the same taste in popular culture and worldview as them (Insane Clown Posse is mentioned a lot).

Merritt’s teaming up with Brown doesn’t feel exploitive. Instead the book reads like a better-educated, better-connected older brother, just a few years more mature than the younger brother, coming in to lend a hand and help him tell his story in a structured, presentable manner. It’s biased as hell, but how could it not be? Brooks was indirectly involved in the massacre just from being good friends with Eric and Dylan. He was notoriously the only person Eric told to leave before they planted the bombs in the cafeteria. Eric spared him because he was a kindred soul.

If you want a clearer picture of what was going on with Eric and Dylan, then you cannot ignore what Brooks has to say:

“The problem was that the bullies were popular with the administration. Meanwhile, we were the ‘trouble kids’ because we didn’t seem to fit in with the grand order of things. Kids who played football were doing what you’re supposed to do in high school. Kids like us, who dressed a little differently and were into different things, made teachers nervous. They weren’t interested in reaching out to us. They wanted to keep us at arm’s length, and if they had the chance to take us down, they would.”

* * *

He describes a school where teachers got swept up in the jock-nerd-normal-freak-popular-unpopular-cool-uncool paradigm, and argues that while Eric and Dylan were responsible for their own atrocious actions, “Columbine [was] responsible for creating Eric and Dylan.”

Brown and Merritt spend a lot of time speculating about “The Basement Tapes.” The police confiscated videotapes with approximately three hours of footage of Eric and Dylan outfitting themselves, testing out their weapons, and leaving behind testimonials explaining why they were going to attack the school. The Basement Tapes—named because most of the footage was shot in their basements—have never been released to the public. Only select members of the press have seen them, and Brooks Brown’s mother and father, who were not invited to the screening, but barged their way in, threatening court action if they were not allowed to watch.

The Jefferson County sheriff’s department’s transcripts of The Basement Tapes can now be found online, but the entire footage still remains locked away. This is a description of part of the second Basement Tape from the Rocky Mountain News “War Is War,” December 13, 1999:

They explain over and over why they want to kill as many people as they can. Kids taunted them in elementary school, in middle school, in high school. Adults wouldn’t let them strike back, to fight their tormentors, the way such disputes once were settled in schoolyards. So they gritted their teeth. And their rage grew. “It’s humanity,” Klebold says, flipping an obscene gesture toward the camera. “Look at what you made,” he tells the world. “You’re fucking shit, you humans, and you deserve to die.” … They speak at length about all the people who wronged them. “You’ve given us shit for years,” Klebold says. “You’re fucking going to pay for all the shit. We don’t give a shit because we’re going to die doing it.”

* * *

Eric and Dylan planned to die in the attack.

This is Brooks’ description of the video, secondhand from his mother’s account of it:

Dylan asks Eric if he thinks the cops will listen to the entire video. Eric replies that he believes the cops will chop the video up into little pieces, “and the police will just show the public what they want it to look like.” They suggest delivering the videos to TV stations right before the attack. After all, they want people to know that they feel they have reasons.

“We are but aren’t psycho,” they say.

Dylan promises his parents that there was nothing they could have done to stop him. According to the Rocky Mountain News article “War Is War,” “You can’t understand what we feel,” he says. “You can’t understand, no matter how much you think you can.”

The Rocky Mountain News quoted Eric as offering praise for his parents. “My parents are the best fucking parents I have ever known,” he says. “My dad is great. I wish I was a fucking sociopath so I don’t have any remorse, but I do. This is going to tear them apart.They will never forget it.”

According to police reports, Eric expresses regret on another tape as well. He recorded one segment while driving alone in his car. “It’s a weird feeling, knowing you’re going to be dead in two and a half weeks,” he says to the camera. He talks about the co-workers he will miss, and says he wishes he could have revisited Michigan and “old friends.” The officer who viewed this tape wrote that, “at this point he becomes silent and appears to start crying, wiping a tear from the side of his face…[H]e reaches toward the camera and shuts it off.”

Their final tape is less than two minutes long. Eric, behind the camera, tells Dylan, “Say it now.”

“Hey, Mom. Gotta go,” Dylan says to the camera. “It’s about half an hour before our little judgment day. I just wanted to apologize to you guys for any crap this might instigate as far as [inaudible] or something. Just know that I’m going to a better place than here. I didn’t like life too much and I know I’ll be happier wherever the fuck I go. So I’m gone.”

* * *

They sound as if they had reached enlightenment. They believed they were dying for a just cause. I believe the reason the Basement Tapes have never been shown to the public is because Eric and Dylan show remorse for what they are about to do.

* * *

Are you married? Do you have a girlfriend? Do you have a boyfriend? Do you want a boyfriend?

That’s the string of questions I get, an algorithm they’ve designed to figure out what kind of a person I am. I know it isn’t designed specifically to discover if I’m gay, but that is one of the possible outcomes. I like to think Brad, a student teacher who is 10 years younger than me, has it easy because he’s engaged to a female. But then I realize their algorithm would just lead to dozens of annoying questions about his fiancé. So maybe I am better off.

Note to self: Come up with clever, condescending answer to the question, “Do you want a boyfriend?” I get extra points if the answer is condescending because if my answer makes the question seem silly, it will cause everyone to laugh, thus putting an end to the line of questioning. I get asked about my tattoo and earrings on a daily basis. It took me six months to come up with this: “Is that a tattoo?” “No, it’s an ink bracelet.”

It’s only a matter of time before someone wises up and asks, “Have you ever had a boyfriend?” I don’t know what I would answer if a student asked me that. Do I wait to cross that bridge when I come to it, or do I prepare an answer? Why am I putting off coming up with an answer? WHAT KIND OF A PERSON AM I?

A student asked me straight-up if the teacher I was subbing for smokes pot. I told him I didn’t know her that well. When I recounted this story to my mother, she said what she would have said was, “Even if I knew, I wouldn’t tell you.” I don’t like that answer—even though it did pop into my head—because it implies that I do know. I think if Ms. X does smoke pot, then there are very few colleagues who know about it, if any. A teacher busted with marijuana would be an automatic firing, likely a career-ender. Whereas in my case, being gay is no longer a crime, but the ice on the slope upon which I tread is both thin and slippery.

I read a recent story about a cross country coach in Colorado who came out of the closet to his school board. They told him he could keep his coaching job, on the condition he no longer go into the men’s locker room while the male team members were dressing. This coach was forced to change in a men’s room separate from the locker room until the assistant coach, who identified as straight, came to tell him all the male team members were fully clothed.

I don’t understand things like that. If I go to the YMCA they don’t have a separate locker room for gay men and women. I have had to teach gym classes, and it has been expected of me to watch over the men’s locker room. Every time I think to myself, If the people in charge knew about me, they wouldn’t want me doing this. At the same time I’m also thinking, I’m not a pervert.

Young people have changed, I suppose. Highlights, earrings, hipster attire. All of the things that elicited catcalls of faggot in my day, that only the brave dared adorn in the name of fashion and individuality, are now commonplace and perhaps even worse, crafted by moms. Sure the adolescents now have been brought up in the “information age” and therefore “interface” with the world more than they experience it. They’re exposed to more sexually graphic and violent media than any generation before them. If you just talk to them, though, you’ll find out they’re not that different than we were. I don’t think anyone looked at my class in the 90s and said, “Yep, they’re exactly like the students in the 80s, 70s, 60s. Not a single thing has changed.”

The generation I am teaching have been watching Glee for the past four years, were brought up on reruns of Will & Grace. It’s not uncommon for students to come out as early as middle school. Teachers have told me to “keep an eye out” for same-sex couples holding hands, that if I catch them kissing I’m supposed to enforce the same rules we have for everybody. These teachers roll their eyes about it, say these students are simply going through “phases;” trying to get attention and piss off their parents. It’s the equivalent of what was said about interracial couples when I was in high school, which is now much more common.

I just don’t know where my place is, as a substitute. I’m not going to run into classes and announce I’m gay. But what if something gay comes up, topically, during class? Can I talk to them about my experiences as a gay man? Can I point out gay subtext in books? Or when I know an author is gay? Or historical figures? No one has ever had this conversation with me.

Let me explain how my job works. If a teacher has called in sick during the evening or early morning, the school district’s personnel coordinator will call me between six and seven-AM and ask if I am available to sub that day. We also schedule ahead of time, if a teacher has requested time off. The more I answer my phone in the morning and show that I am reliable, the more the personnel director will continue calling me. The more I teach and have favorable comments made about me from students, teachers, teaching aides, and front office workers, whomever it is I work with, the more I get called for work. My job is dependent upon my performance.

I feel good about giving back to the community. I find it immensely rewarding to help educate young people. What frightens me is ever losing my job for censorship reasons. For misspeaking. For my sociopolitical and religious beliefs, and having those misconstrued as trying to spread “perversion.”

I have a gay friend who was a teaching aide in this district just ten years ago. Some students found his online dating profile. He had listed himself as “Interested In Men.” This profile did not say anything about looking for sexual encounters. There were no photos of him naked or even shirtless. Simply listing himself as looking for a relationship with another man was enough for the school to ask him for his resignation. I just don’t know if I could handle that. Or maybe coming to that is the inevitable conclusion for this job.

I’ve heard of two high school teachers telling their classes extremely homophobic things. One told her class that homosexuality is a perversion equal to bestiality. Another told her students that homosexuals go to hell. Teachers who know well enough that many of their past and present students are gay. Some of them screaming-gay.

To the best of my knowledge, I only had one gay teacher. This individual stayed in the closet for his/her entire career. It wasn’t until the last two or three years before retirement that he/she finally opened up his/her private life to some of the faculty. Up until that point, I had always been led to believe it was an open secret. We all knew it, both students and faculty. It was just never directly addressed, unless we were making fun of him for being a fudge-packer who liked getting his fudge packed by other fudge-packers.

I get standoffish with my male students. Let’s say one takes a liking to me, wants to get to know more about me, during periods of downtime in class will stand next to my desk and want to chitchat with me. I become evasive. I’ll suddenly have other things which require my attention. I’ll act like I’m not interested in talking to him. This is because I don’t want anything to be misconstrued, even retroactively. Say like two weeks or two months or two years from now, the student finds out that I am gay and he could start to reform his memories of our chats and hear words that were not said, inflections that were not inflected.

I guess I’m afraid of the rumors starting again. How good are people’s memories, anyway? Not many of the teachers here were teaching when I was in school. Nobody has said anything to me about it. What happened to me fifteen years ago.

* * *

The rumor Nate and Scott spread around the school was that my friend Chad and I were gay for each other. If I was going to retaliate, I had to include Chad in my plan because they slurred his name, too. Thing was, while I was actually gay, Chad wasn’t. We had been seen flirting, sure, so that was a reasonable conclusion for Nate and Scott to jump to, but Chad and I both knew it just wasn’t his thing. But, still, the rumor included him, and therefore any retaliation had to include him.

The easy way to go about fighting back would have been to spread an equally nasty rumor about Nate and Scott. Not only did I not have any dirt on them, I felt spreading more rumors would only exacerbate their animosity toward me.

What I really needed was a way to dispel the rumors about Chad and me that would also call Nate and Scott out on their shady tactic of attacking us with gossip. I wanted to call bullshit not just on the rumor, but on gossip in the grander sense. They could say anything they wanted to about me. People talk, but it’s everyone’s choice of whether to listen to gossip. The only way to know a person is to talk and interact with him.

I called Chad and pitched him my idea. We had to throw this back in their faces. Yeah, it would blow over in time, but if we were going to do something about it, now was the time. We had to strike. I wanted to do something that would get the whole school to pay attention. I wanted to make a statement.

I went out and bought two white T-shirts, and a big black marker.

The thing that surprised me was, everybody got it. People were running up to me in the hallways, asking to see the shirt, telling me to turn around and show the back. High fives, hugs. If we’d had digital cameras back then, people would have been taking photos with me. I was the most talked-about person in school for two consecutive days: one that branded me a pariah; the next I was a brave, clever, funny kid with a positive message to give the world. I walked the halls with my head held high. I smiled so much that day I could have died.

A few teachers stopped and asked to see my shirt. Most shook their heads and rolled their eyes at me. Some said they thought it was great, high-fived me. A couple of them stood together, deliberating what they should do about it, but I kept winning. The only teacher I thought I had to worry about was Mrs. Loomis, my Trigonometry teacher. We had been butting heads all year. She called me to the front of her class and asked to see the shirt. Of course I took the opportunity to show it off to the room, and gave my little speech. In large letters, covering the entire front it said: I’M STRAIGHT . . . and on the back it said . . . CHAD ISN’T.

Mrs. Loomis asked, “Does this ‘Chad’ person know about this?” I assured her he did, and in fact he was wearing a shirt that said: I’M STRAIGHT. . . . . . KYLE ISN’T. I told her we were demonstrating against rumors. She looked annoyed, but couldn’t find anything offensive about the shirt, so she left me alone.

If I had written on the shirt, “I’m not gay…Chad is,” the word “gay” might have been too shocking. I had learned from my experience sophomore year with the teacher telling me to turn my shirt inside-out because it had the word “hell” on it. There would likely be a faculty member who found the word “gay” to be dirty, so I flipped the phrase. Also, Chad and I wearing shirts that said the same thing about each other had a canceling effect. We were both in on the joke, not attacking each other.

* * *

Author Dave Cullen spent ten years writing Columbine, the most comprehensive account of the before, during, and after of the massacre. The book follows the stories of Dr. Fuselier, an FBI investigator whose son attended Columbine High School, and went on to put together a massive report on Harris and Klebold; Dave Sanders, the one teacher killed in the attack, who saved countless people that day; the brave principal Frank DeAngelis, who has remained at the school and retired in the spring of 2014; some of the injured students; and of course the killers themselves. But there is a conspicuous lack of teacher’s impressions of Eric and Dylan. Many moved after the massacre and understandably wanted to put it behind them.

Brooks Brown’s role in the story is underplayed by Cullen. This may be because he didn’t want to cover too much of what was already in Brown’s memoir, but there is unmistakable tension between Cullen and Brown underlying the text. He makes Brooks out to be a tattletale. When Dylan was unsure whether he wanted to go through with the bombing, he leaked information to Brooks because he knew he and his interfering mother would go to the police. Nothing ever came of their many attempts to get the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department to investigate Eric. After the massacre a search warrant for Eric Harris’s house was discovered, made out in full, but was never taken to a judge to be signed. Cullen mentions this, but doesn’t pay much respect to the Browns as the only people in the community who identified Eric as an unstable person, ready to blow any moment. Instead Cullen makes Brooks Brown out to be a media whore, overplaying the “bullying” factor in the killers’ motives.

Fuselier was fascinated with Eric’s journals. They were used as the primary documents to diagnose Eric as a psychopath. Cullen doesn’t question this diagnosis in his book. It is the popular conclusion the psychological community has signed off on. This is preposterous to begin with because how can you diagnose a person with such an extreme personality disorder without having met him? I have not been able to find anything suggesting Dr. Fuselier did any outside research. Did it ever occur to him to listen to KMFDM, and to analyze their song lyrics?

To get you to the point I’m trying to make, let me illuminate for you one more similarity between Dylan and myself: We were both big fans of the industrial band Nine Inch Nails. Dylan especially liked The Downward Spiral, which is bandleader Trent Reznor’s concept album about a protagonist contemplating, then ultimately committing suicide.

If you read my private writings from when I was a teen through my early twenties, I seemed to have adapted the style of Reznor: bleak, melodramatic, self-obsessed, yearning to find a connection to the outside world, while keeping it at arm’s length. That’s how Dylan felt. Of course the music did not cause us to feel that way. He and I were drawn to Nine Inch Nails because we already felt that way. Music helps us explore emotions that we are already experiencing.

If you were to read Eric’s journals and KMFDM’s lyrics side by side, you would find a lot of similarities. Yes, these were Eric’s original thoughts, but he was copying the aesthetic of KMFDM. His journals take on similar structure and themes, the same as Dylan and I were copying Trent Reznor’s.

A person of average intelligence will memorize a song, may write out the lyrics verbatim, the way they were given to him. A person of above average intelligence will emulate the style of song lyrics and structures to write their own.

I am in no way endorsing the theory that violent music is responsible for Eric and Dylan’s actions. If it hadn’t been KMFDM and Nine Inch Nails, they could have just as easily been reading Dante’s Inferno, Faust, or could have found violence within the music of Beethoven or Wagner. To attack art would be to attack a mirror. What I’m trying to say is Dr. Fuselier came up short for not having caught onto the fact that Eric’s rantings were invoking a style of lyricism. Eric was writing poetry. He was creating art.

Was Eric truly a psychopath? Why do I have such a hard time labeling him that? It’s because the more I look into it, the less I believe there even is such a thing as psychopathy. A recent article in Scientific American caught my attention. It’s about a new school of thought about the Belief in Pure Evil (BPE), and how it affects a person’s ethics:

According to this research, one of the central features of BPE is evil’s perceived immutability. Evil people are born evil – they cannot change. Two judgments follow from this perspective: 1) evil people cannot be rehabilitated, and 2) the eradication of evil requires only the eradication of all the evil people. Following this logic, the researchers tested the hypothesis that there would be a relationship between BPE and the desire to aggress towards and punish wrong-doers.

* * *

Researchers have found support for this hypothesis across several papers containing multiple studies, and employing diverse methodologies. BPE predicts such effects as: harsher punishments for crimes (e.g. murder, assault, theft), stronger reported support for the death penalty, and decreased support for criminal rehabilitation. Follow-up studies corroborate these findings, showing that BPE also predicts the degree to which participants perceive the world to be dangerous and vile, the perceived need for preemptive military aggression to solve conflicts, and reported support for torture.

* * *

Psychopathy is defined as a personality disorder which includes antisocial behavior, diminished capacity for empathy or remorse, little control over behavior, and superiority complex. They say psychopaths (which is interchangeable with “sociopath”), while lacking the human emotions of sorrow, sadness, empathy, learn at an early age how to imitate these in order to live alongside fellow human beings. Doesn’t that describe everyone?

Eric was not a psychopath until after he had already killed thirteen people and himself. Before that he was just a boy. With a strict father he loathed but respected. A mother he loved tenderly, but also found annoying. He hated the world. Hated everyone except for people who agreed with his worldview. There weren’t any, really. He probably didn’t even like Dylan that much, but knew from the start he could manipulate him. In a way Dylan was his first pipe bomb. Did Eric believe in God? I know he did. He thought he was godlike and that only he and God truly understood the world.

Eric wanted anarchy. He wanted us all to start killing each other, to arm ourselves to the teeth, to suspect our neighbors of trespasses against us, to prepare for war within our own borders, against each other. That message was received, loud and clear. Well done, Eric.

Empathy is a learned behavior. Some people may be harder to teach than others, but that doesn’t mean we should throw up our hands and say it’s pointless to try. That’s the current philosophy of our education system. We target those who are good at subjects and those who are bad, and set our focus on them, leaving the ones in the middle alone. We don’t put forth the intensity or the manpower it would require to teach everyone equally. A system that should be a stronghold of egalitarianism has been rendered a socially Darwinistic and paranoid-survivalistic state.

We need to quit being afraid of each other, to show our children how to be fearless. Instead of fortifying our schools to keep people out, we need to start letting more people in.

* * *

After that day Nate and Scott buried their grudge against me. I heard through the grapevine that Nate decided if I was willing to go that far, then it wasn’t worth his time to mess with me anymore. Things settled down after that. People sifted through the rumors, though, and eventually came around to the truth. Nate, Scott, and the friends I’d come out to assured people I really was gay, but they had been mistaken about Chad. The rumors about Chad going away were also aided by the fact he was going around telling people I was the gay one and he didn’t know how he got roped into the rumor. He even got some of the girls he had slept with to “vouch” for him.

Eventually I realized that on the day of the t-shirts, I hadn’t seen Chad at all since I gave him a ride to school and we put the shirts on in my van. He had taken different routes to his classes to avoid me. Later I got it out of him that, “It was too cold to wear just a t-shirt that day.” He had covered it up with a sweatshirt. He still “technically” wore it. Like that meant anything.

Things did not get better. People quit inviting me to parties. The mutual friends I had with Nate and Scott had to decide who they were going to hang out with. It wasn’t so much a question of loyalty as it was whether they wanted to hang out with the cool guys, or the gay guy who took things a little too far.

The rumor happened about three weeks after I had come out to my family. When Scott called me to warn me “the whole school” was about to find out I was gay, I told my parents about it. We discussed possibly dropping out and getting a GED, maybe going to live with my uncle and enrolling in school there. I decided I would brave it out. I didn’t want to “run away from my problems.” But now when I think back, returning to that school day after day did something to me.

The next fall I went back to school a broken person. I quit all of my activities. Classes were a joke to me. In November I was arrested for possession of alcohol and five counts of drug paraphernalia.

The next morning I went to swimming class early and told my teacher, Mr. Tobias about my arrest. I wanted him to hear it from me before he read about it in the paper. He was the only teacher I had left whom I felt like I got any respect from. He gave me a short, impromptu speech about how this was going to be a “dark mark” on my life and I would have to work hard to restore people’s faith in me.

The next day, after it was in the paper, I saw my sophomore year biology teacher, Mr. Levin in the library. He yelled, “Get over here!,” put me in a headlock, said, “You’re going to shut up and you’re going to listen to me. You fucked up. You know that, don’t you? Nod your head if you understand. Now you’re going to quit fucking up, right?”

Those two were the only teachers who said anything to me about it at all. It was hard to live up to either of their advice in the short term. I made a swift decision to graduate early.

My swan song to high school was my final report card. It read: ABCDF. I orchestrated that. I knew exactly how much effort to put into each class to get the grade that I wanted. It was a joke I’m sure at the time only I found funny. A joke on how arbitrary grades are. A joke on my younger self for my goal to get straight-A’s all through high school. My goal to be valedictorian, to earn a National Honors Scholarship. Goals that had at one point all been well within my reach.

It got worse. After I graduated I got arrested again. Alcohol again, but this time I also had marijuana in my possession, not just paraphernalia. I lost my job as a lifeguard. My employers had overlooked the first arrest because I went to Teen Court, did community service, and proved I was clean by passing a drug test.

At the end of my first semester of college I flunked all of my classes, dropped down to two classes my second semester, and just barely passed those. I was so jaded by my high school experience that I lost all work ethic and still held onto hostility toward educational institutions, even while I was attending a completely different, much more accepting one. This behavior continued well into my twenties, as I slowly built myself back into a semblance of the student I used to be, albeit a deeply scarred one.

I know I’m being maudlin about my experience, but keep in mind I’m telling it to you the way I have told it to myself over and over again. I want to take full responsibility for my fucking everything up, but I know it wasn’t completely my fault. The school failed me. My parents noticed all of this as I was quite oblivious to where the school was not doing its job. The year after I graduated my father even wrote a letter to the school board, urging them to scrap their oppressive Secondary Code of Conduct:

[Kyle] went from being tied for first in his class at the end of his freshman year to 94th ….the administrative support for students at the front office does not exist except for scheduling and discipline. What appears to be so obvious a need and so simple to implement keeps on going unattended year after year! All that happens is progress in making new rules to discourage kids or get them to drop out or graduate early.

My daughter has recently started working for teen court. In the short time she has been there she has noticed a pattern of kids in trouble with the law. A frequent beginning is a kid getting into trouble at school. An example is too many tardies resulting in ISSP[2] and sometimes the punishment has been 3 ISSPs. During ISSP many teachers do not cooperate in giving homework or make-up work. The result has been in many cases the student going from B – A student to D – F. Once that happens, the student is discouraged and the risk of dropping out increases. After Kyle was arrested, my review of the facts of the arrest led me to the conclusion that he could have easily prevailed in criminal court because of many factors based upon his constitutional rights and the statutes. Basically, the arrest should not have occurred. We chose not to fight the charges. Nonetheless, Kyle, a kid who needs help and encouragement, was suspended for 30 days from all activities. When receiving his sentence from the school district, I asked what suggestions the district representative had for helping Kyle get back on track. The school representative’s response was “Kyle is trying to find himself.” No suggestions were offered i.e. that is your problem not ours.

* * *

I’m not trying to say school officials had to cater to my every need. But what my dad and I are trying to understand is what good is coming from what they are doing?

I didn’t need to be medicated. I know that much. I needed someone to take an interest in me. I needed a support system to check up on me, to let me express what I was going through.

A couple years ago I got together with my freshman year English teacher. We spent three hours one afternoon, talking over coffee. I told her early in the conversation that I was gay, and that I am very concerned about the nation’s recent spike in teenage suicide. Then I brought up the weekly journals she assigned, that were an open source for all of her students to write about things that were on their minds. My parents saved all of their children’s important schoolwork, and I had recently gone through all of mine. I read through all the journals I had written for Miss Schneider, even transcribed them to my computer.

Reading them as an adult, it was clear to me that what I was looking at were the guarded confessions of a gay teen. Although I did not come out directly to Miss Schneider in them, I was trying to clear a path to that process. You can see me working through these questions on the page. My intense feelings for one boy in particular were the subject of many of these journals. There were entire entries about my frustration with friends who made gay jokes about me at overnights, more so than the any of the other guys in our group. They caught onto it very early. Earlier than I did.

I told all of this to Miss Schneider, in a long, multipart question I had forming for her, because I was sure she must have had some dilemma of her own, about where her place was in this matter, knowing she could lose her job if she suggested to a fifteen year old that he might be gay. Did she think about trying to simply foster me in some way, to guide me so I would figure it out for myself, all the while suggesting her classroom was a safe place for me?

Her answer disquieted me. She never had a clue. She said she doesn’t look at people “that way.” I didn’t have the spirit left to ask her what she meant by “that way.”

* * *

I look at what Eric and Dylan did and what I did on a spectrum. On one end of the spectrum is the very worst possible thing a person can do: mass homicide; killing innocent people. Next to that would be suicide. I’m somewhere over on the other side of the spectrum. Coming out probably would have been then best possible thing I could have done, but I didn’t quite do that. I made a statement, but it was the wrong statement. I addressed it. Kept going to school. Survived. Didn’t kill anybody. Although I wanted to.

I did the thing that was right for me in that moment. I don’t know if at the age of 17 I was capable of coming totally out. I did go to high school with people who were out. Some of them had been out since grade school. They told their families. They all had time to prepare for the stormy future. Those early ones, the proud ones, they were the ones whose property got vandalized. Who got the harassing phone calls. Who went out to the parking lot every day hoping their cars weren’t vandalized again. Who couldn’t go up to the front of the classroom without hearing someone pretend to cough and say the word “dyke” or “faggot.” Who people quit making eye contact with in middle school. Who felt unsafe every day of their lives.

I also have friends who came out later than I did, who waited until college like my parents would have liked for me to have done. I also have friends my age—early thirties—who are still not out. And yes, I have known people who were out to only a few people, and decided to kill themselves instead of trying to live their lives out in the open.

The morning of Columbine was the day after my grandmother’s funeral. My family had buried both of my father’s parents in less than one week from each other. They died one after the other, within days. Bang Bang. My grandfather was my best friend. We became close over the past seven or eight years since his wife started losing her mind and was in and out of nursing homes. He died without knowing I was gay.

I had come out to my parents and older siblings a little over a year before his death, just weeks before I was outed at school. My parents instructed me to not tell my grandfather and to wait for my younger siblings to get a little bit older before I told them. In fact, my parents asked exactly how many people I had told, suggested maybe that was enough, and to refrain from telling anybody else. They were pissed this embarrassing secret had gone outside the family. To them, my belief that I was gay was something that should go through a test phase with the family first, because what if I didn’t feel the same way in five, ten years? Because then I would wish I could go back and unsay the things I had said.

How little straight people understand about what the closet is like and why we feel the need to come out. For years I debated whether my grandfather died without “knowing the real me.” I hear so many gay men say being gay is “the least interesting thing about them.” I cringe at the cliche of it, even though I agree. There are days I don’t even want it brought up in conversation, but we all know those people who always have to make it part of every conversation they have with us. No, it is not the most interesting thing about me, but I will say this: It is essential information about me. Anyone in my life who does not know it, up until the moment I tell them, our relationship has been predicated on a lie.

I feel like I am lying to my students every day. They could learn from knowing the true me. I feel like I am hiding myself from my colleagues, who could also learn from knowing the true me. Perhaps they won’t even mind that much. I haven’t given them the chance to have that discourse with me.

* * *

My mother looked at me like she didn’t know who I was anymore. My words exactly to her were: “Don’t be surprised if this happens more often.” I said that the morning she told me there were kids shooting people at their high school. The day we now refer to as “Columbine.”

She and my father were mortified. “What do you mean?” she asked, like I knew something she didn’t. Like us teenagers were using the Internet to organize this sort of thing.

“I just mean kids are really pissed off nowadays, Mom. There’s a lot of hatred in the air at high schools. You can sense it. It doesn’t surprise me that a teenager would take a gun into his high school and shoot up the place. In fact, I’m surprised it doesn’t happen more often.”

I followed that up with, “I’m going to TJ’s.” The Columbine massacre happened on April 20th—the holiday of pot smokers. Graduated early from high school, I was living in my parents’ attic, a sexless gay eighteen year-old who had just broken up with the girl I had been dating to try to assimilate to hetero-normativity, and I had just put two of my grandparents in the ground. I was going to get high as fuck that day.

My friends and I bought a lot of weed and had a longterm plan in place for that day, but it got interrupted for the first few hours because we were watching live footage on CNN of this atrocity. We were back-and-forth watching it, trying to pull ourselves up out of it and have a good time, but at the same time acknowledging how terrifying it was and how we hoped people would survive, although we were mature enough to realize there were going to be casualties. I remember the whiteboard up against the window: 1 BLEEDING TO DEATH.

We also understood that it could have been happening to us, that one of our fellow students, somebody maybe we never even would have suspected, some kid who you never even knew his first name, could pull something like this. And that’s who we suspected these kids were.

As we watched the footage I said something even more macabre to my best friend, Mark. In complete confidence I solemnly said to him how I really felt about the massacre taking place before us on live television.

The more I sat there watching it unfold on TV, I thought back to that night, lying in my bed in my pitch dark room. How badly I wanted to do what those kids were now doing at their school. And the more I thought about it that day in 1999, I had to let it out to somebody. I leaned over to Mark, told him in total confidence, and just out of a place that I needed to let this thing out, I said, “You know those two kids in there, shooting up their school? They’ve got to be having the most fun they’ve ever had in their lives.”

* * *

The first attack on a school in the US was in 1927. There were none between then and 1966. Between 1966 and 1999 there were 46. That is 1.39 a year.

Since April 20th, 1999 there have been 75 attacks on schools. 5.35 a year. Meaning one every 68 days. That’s one every two months since Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. That’s 3.85 times the frequency they occurred before April 20th, 1999. Attacks on schools have quadrupled in frequency since Eric and Dylan.

Overheard during the Columbine massacre: “This is what we always wanted to do. This is awesome!” “Who wants to be killed next?” “Peekaboo!”

They were laughing a lot, joking back and forth to each other from across the halls as they tossed bombs and blasted their firearms. They questioned victims, laughed sadistically at whatever they answered—everything was a joke to them by that point. There were no correct answers to save your life. Some they shot, some they left alone. Everything was random—because they still wanted to blow up the school. They picked people off for fun as they made their way to the cafeteria, where they tried to detonate the bombs manually. This failed, so they retreated to the library, where each shot himself in the head. On the count of three.

Dylan’s shirt said WRATH. Eric’s said NATURAL SELECTION.

They split a pair of black gloves. Klebold wore one on his left hand. Harris wore one on his right. No one can explain why they did this.

* * *

Will and some of his friends and I are standing at that strange nexus between the doorway and the hall, that little space of freedom students are always inching towards at the end of a period, and it’s up to me to draw my own version of the arbitrary line they are not supposed to cross. I’ve subbed for Will four times by my count. He’s the kind of student who tries to push the boundaries in the student-teacher relationship—he was the one who asked me if the teacher I was subbing for smoked pot. Will is tall, blond, cute in an Anthony Michael Hall way, and I think he knows it. He’s smart, but hip, and his shirts are always conspicuously slogan-free.

Will asks me what my tattoo represents. I give him an honest answer: it’s an infinity symbol wrapped around my wrist. He presses, “But what does it mean to you?”

I launch into how it represents my belief in an infinite number of parallel universes. I explain: “It used to be science fiction, but now it’s a widely-accepted theory. And they even say that when parallel universes come into contact with each other, a new Big Bang occurs and a new universe is created. So Big Bangs are happening all the time all around us, but we just haven’t figured out how to detect them yet.”