Plums For Months by Zaji Cox

A Book Review by Deb DeBates

I watch as Micah walks through the gray doors of his high school and crosses the parking lot. He is smiling, and in his usual slow gait, crosses the street in front of a long row of school buses. It’s a frigid winter day. I quickly unlock the passenger door so he can enter without hesitation.

“Hey kiddo.” I take his backpack, help him remove his puffy black parka.

“Hi mom.” He looks at me, then stares at my phone. I know he wants to watch movie clips on YouTube. It’s his way of unwinding on the thirty-minute drive home.

But he knows the drill.

“Tell me about your day.”

He mutters something about gym or performing arts, his two favorite classes, then falls silent.

“What was the kindest thing you did for someone today?” I’ve had luck with this one before.

“Mom, no more questions!” I sigh and hand him my phone. Perhaps he’ll tell me more on another day.

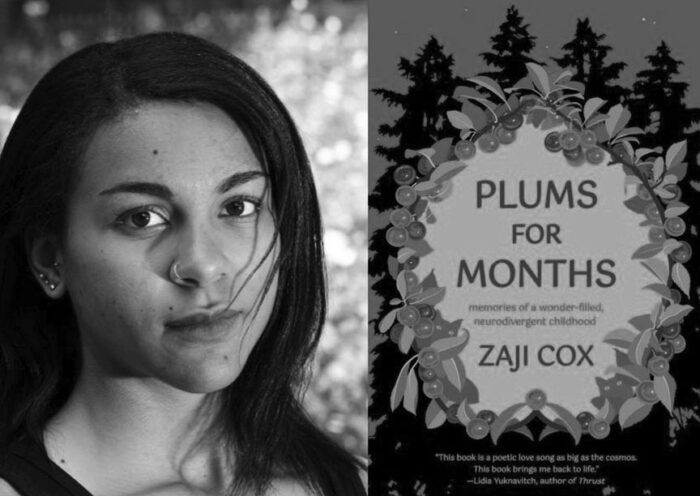

This familiar scene in my life reminds me of the book, Plums for Months, by Zaji Cox, a beautifully written collection of short essays in which Cox shares snapshots of her life growing up on the outskirts of Portland, Oregon. The author is keenly aware of her surroundings, her feelings, and emotions, describing it all in wonderful sensory and visual detail. I found her memoir to be intelligent, heartwarming, and often bittersweet.

My son is as Cox describes herself to be—neurodivergent. Micah is on the autism spectrum, and although Cox does not use that diagnosis in her writing, she does divulge about her struggles with non-verbal cues and social interaction, skills most individuals with autism have difficulty with as well. It is the foremost reason I loved this book so much—she articulates so well what it’s like to process the world around her differently and to face such challenges.

In one essay entitled, “The Intricacies of Social Interaction,” Cox explains this struggle and how she uses the tool of observation hoping to learn social skills that come so naturally to others. She draws the reader into a restaurant scene where she is with her sister and a few of her sister’s friends:

…between bites I’m observing and taking mental notes like usual: the lilt of their voices in casual speak; the rise of an eyebrow when making a joke; the blank look during a moment of sarcasm; how they sit, how they stand, how they gesture.

Reading this story brought me back to my son being mainstreamed into classes and extracurricular activities with those who are neurotypical so that he has the chance to learn, as Cox does, through watchfulness and interaction. Micah’s interest in performing arts has led to his participation in school plays and summer theater programs during which he’s absorbed a variety of social cues from his neurotypical peers. I can’t be certain that he is intentional in his observation as Cox is, but it is possible to learn social skills through osmosis—absorbing behaviors while participating in a group. The improv and sketch comedy classes Micah is taking this summer have given him the opportunity to learn how to think on his feet and jump into a scene like the other kids do. Being included with neurotypical peers gives him the chance to watch, to learn, and then try. He is improving in interjecting lines that are original and appropriate instead of phrases said by favorite Marvel characters like Spiderman or Black Panther or perhaps Scar from The Lion King, a movie he has watched dozens of times.

In this essay and others, Cox illuminates how being around neurotypical peers can help one learn to live in this world more effectively. It’s how most of us learn social skills, and why it’s vitally important for a child or teenager with autism to have ample time in community with others both on and off the spectrum. When my son was much younger, I enrolled him in a mostly neurotypical gymnastics camp. Jumping on the blue spongy floor trampolines, climbing rock walls, and being able to play games and run around amidst these peers also gave him the opportunity to learn turn taking, sharing, and how to encourage others.

Cox writes about living with her mother and sister in her grandfather’s time-worn 100-year-old house. Her close relationship with both her sister and her mother is reflected in much of her writing as is her fascination and connection with nature — especially the feral cats that often visit them on this property. Her essays about the cats were thoroughly delightful and, for me, so relatable because of Micah’s similar connection with animals, his being dogs (although he would love for me to give him a cat or two). Like Cox’s fascination with the wild felines that loiter on their property, Micah has always been enthralled with a larger variety of feral cat–the mountain lions at our local zoo. He could spend hours watching them prowl around in their not-nearly-large-enough cage.

Cox also shares about her domestic cat, Jerry, who is a warm companion. “I soon find in Jerry a listener,” she writes, “He is there when I can’t communicate right with the human world to which I supposedly belong.” I love that she has touched on the importance of animals in her life; I see this same relationship with Micah and our black lab mix who is always there for him to sit and snuggle with after long days at school, who helps him decompress and be comforted after being in a largely neurotypical world.

This book is so well written, and not surprisingly, as Cox is an avid reader, writer, and lover of books as she demonstrates in her essay, “The Scholastic Book Fair.” In this brief, yet beautiful and bittersweet piece, she takes the reader with her to her school’s book fair where she peruses the shelves knowing she has money for just one or two. She watches as her peers, able to have all they desire, load their arms with merchandise. She imagines her bedroom filled with towers of books separated into genres and categorized by ones read, not yet read, and those worthy of being read again. She soothes herself by inventing a way she can have as many as she wants: “I will simply pay for them with need.”

There are so many other topics Cox covers–gymnastics and dance, dealings with boys, friends, frustrations (and triumphs) with her hair, and shopping at Goodwill. Her essays are a sensory feast bursting with vividness, so much so that I felt I had been in her mind seeing her view of the world. Plums for Months is a book for all ages and for all walks of life. Through Cox’s essays, we learn so much about being human, about wanting to fit in, to achieve, and to feel the warmth, friendship, and love of others.

Oh, how I wish I could plumb the depths of my son’s inner world as Cox has done with hers. For now, I remain inspired by Plums for Months to see beyond the outer layer not only of those who fall outside the neurotypical category, but of everyone I meet—to look more deeply, with more patience, with more love.

BIO

Deb DeBates is a writer and parent of a son with autism and type 1 diabetes. Her experience inspired her to start a blog, micahandme.com, to help raise awareness about all aspects of raising a child with these diagnoses and to encourage others who are on a similar journey. She lives in Southeastern North Dakota with her husband and two children.