The Adults

by Paisley Kauffmann

It began as it always began. A man was there in the morning calling Joe, buddy or pal. The man would pillage their refrigerator, watch their TV, and shit in their toilet. This man, like the others, was tall and probably considered attractive. He had striking blue eyes with long black eyelashes. This man, like many of the others, bore intricate tattoos detailing the significant detours of his life. This man had a daughter.

On Saturday, Joe woke up early to play video games before his mother would insist on turning the channel to a reality show. He kicked through the clothes on the floor until he found his favorite tee shirt left behind by the last boyfriend and pulled it over his head. Tiptoeing past the shut door of his mother’s bedroom into the small living room, he discovered a small figure covered in a flannel shirt sleeping on the couch. Motionless, he stared at the round cheeks and pink, puckered lips of the intruding, unknown child. With a stab of disappointment, he decided it was a girl. He had wanted a brother. The girl snapped open her lids revealing shimmering blue eyes laced with dark feathery lashes. Joe startled, stepped back, and tripped over a pair of size thirteen leather work boots. The little girl smiled but did not move. Joe held his finger to his lips signaling her to stay quiet. Mimicking him, she held her finger to her lips and then stuck her finger into her nose. Joe rolled his eyes.

He waded through empty cigarette cartons, unpaired shoes, and fast food wrappers to his video game. Jamming the power button in a half dozen times, he shook the black box until it resuscitated. He sat on the floor with his back against the couch and ignored her as she wrapped her fingers around his brown curls. The tickling sensation made him inattentive, and he got decimated by a zombie. He closed his eyes and let her light touch put him into a trance.

“Hey, buddy.” Devon’s voice quaked through the room. “How old are you?”

Joe dropped the controller. “I’m eleven-and-a-half.”

“You ever babysit before?”

“No.”

“Well, then now is a great time to start.” Devon swung the refrigerator door open causing the beer bottles to chime together. “I’ll give you five bucks for the day.”

“Twenty.”

“Twenty!” Devon stopped pilfering the refrigerator. “You just said you ain’t never babysat before and now you want to charge some professional rate.”

Joe remained silent.

“Ten.”

Joe resumed pounding on the red button of the controller blasting away at zombies with his laser beam. He always aimed the crosshairs at their heads because, if he hit them just right, the head exploded into satisfying vivid chunks of skull and brain.

“Jeez, kid. Fine. Fifteen.” Devon stood with his hands on his hips.

Joe nodded slightly without moving his gaze from the screen.

“Great,” Devon said, and stuck his head back into to the refrigerator.

Joe glanced over his shoulder at the girl, but she had cocooned herself under the shirt. Devon pulled out the pizza box, leftovers from dinner, and tossed it on the counter. He grabbed a slice of cold pizza, tore off a bite with his large stained teeth, and wandered back to the bedroom. Joe had planned on eating the pizza for breakfast himself, and he would have eaten it immediately if he had known there was going to be competition. The last man, with the cool tee shirts, never ate breakfast. The last man hardly ate anything, only drank. Joe focused on smashing zombie heads and ignored his growling stomach. Devon, barking obscenities, returned to the kitchen and folded the last two pieces of pizza together. He worked his feet inside his leather boots and held the pizza in his teeth while he tied the laces. Devon strode through the apartment searching, first, for a clean shirt and then his car keys.

“Where the fuck are my keys?” Devon said.

Joe’s mother, succumbing to Devon’s tirade, dragged herself from the bedroom into the living room and said, “Well, where’d you put them?”

“If I knew that, Amber, they wouldn’t be lost, would they now?”

“Joe, sweetie?” Amber asked, pressing her thumb and forefinger into the corners of her eyes. “Have you seen Devon’s keys?”

“No,” Joe said. He knew where they were, but he was disinclined to make Devon’s day any easier.

The two adults stomped around the apartment cursing blame at each other about the mess. They took turns banging around the kitchen and shuffling through the shirts and jackets flung on chairs.

“Get up,” Devon said to the red flannel shirt.

The flannel shirt remained still.

“Get. Up.” Devon snatched the shirt off the girl.

With her body curled into a knot, her face was tucked into her knees.

Devon swung the girl off the couch by her arm, and she landed on the matted carpet with a thump. He jabbed his hands between the cushions around Joe, who had no intention of moving.

“Devon. Calm down,” Amber said.

“What’d you just say to me?”

“Look,” she said, pointing at the sliding glass door. “There they are.”

“Where? Outside?” Devon stopped molesting the couch and stood.

“They’re on the ledge of the railing.”

Joe was disappointed in the rapid resolution of Devon’s frustration. Last night, Joe had watched Devon step outside and set his keys down while he lit his cigarette. After Devon flicked his butt from their third floor balcony, which was against Ridgeview Terrace’s policy and could incur a fine, he came inside—forgetting his keys. Joe considered giving them a little push, but Devon was new and his volatility was still unpredictable. After more hustle punctuated with a few sharp words, Devon stormed out slamming the door behind him. His mother flinched, sighed, and turned to Joe, but he ignored her and focused on killing zombies.

In the kitchen, Amber started the coffeemaker and crushed beer cans. The little girl picked up the red flannel and climbed back onto the couch. Waiting for the coffee to percolate, Amber shuffled into the living room and sat cockeyed on the ottoman with a missing wheel. “So, did you meet Mia?”

“Yep.”

“She’s Devon’s daughter, or one of them. He’s got four all together. Three from his ex-wife and this one here from his last girlfriend, who, like a total idiot, got arrested last night trying to buy dope from an undercover,” she said with perverse satisfaction.

“Sounds like you’re babysitting today,” she added.

“I guess.”

“Thanks, because I got to run some errands.”

Amber poured her coffee and sat on the balcony ledge to have her morning blast of caffeine and nicotine to get things moving.

Joe paused his game and turned to look at Mia. She smiled at him with a toothless grin. He snarled at her and she buried her face in the cushion.

Amber, with her platinum blond hair piled into a mess on the top of her head, shoved her cigarettes and phone in her purse. She applied a thick layer of pink lip gloss, and said, “I’ll be back in a few hours,” Amber scrutinized Mia like she was another stain on the carpet, “Keep her out of the bedrooms, she seems kind of dirty.”

“I’m not giving her a bath,” Joe said.

“I know, just keep her out here.”

Joe nodded.

Hungry, Joe paused his game and went into the kitchen. Mia slid off the couch and followed him. Joe opened the refrigerator and searched through the condiments and beer. He found a half package of bologna. He peeled a round slice from the stack, folded it into fourths, and stuck it in his mouth. Mia watched him cram a second slice in with the first. With both cheeks filled with processed pork, he chewed with his mouth open. Mia’s eyes followed his hand as he pulled a third moist piece from the package. He held it up and, like a hypnotist, swung the slice back and forth. Her eyes remained fixed to it. Joe let go, and it hit the floor with a smack. Lunging after it, Mia shoved the bologna in her mouth with both hands swallowing most of it without chewing. Disgusted and bewildered, Joe held out another piece. She froze, waiting for him to release it. He tossed the meat behind her and, again, she scrambled after it. Joe continued to toss Mia bologna until the package was gone. Opening and slamming cupboards, he searched for something else to feed her to continue this fascinating game but was interrupted by a knock at the door. Mia’s eyes grew wide and she covered her mouth. Behind the door, Joe found his buddy Brock with a black eye and a red scooter.

“What happened?” Joe asked.

“Mateo’s older brother found me in their garage.” Brock gasped for air. “I wasn’t going to take anything, but he punched me any ways.”

“Where’d you get the scooter?”

“From Mateo’s garage, but only after he punched me. I better bring it in before he sees me.”

Joe held the door, and Brock rolled the squeaky scooter into the apartment. There was a socioeconomic distinction created by apartment residents with garages and apartment residents without garages.

“Who’s that?” Brock asked.

Mia, covered in a golden powder, peeked out from the kitchen.

“Mia,” Joe said. “Her mom’s in jail.”

“What’s on her face?”

Joe shrugged and led them into the kitchen.

Mia held a box of yellow cake mix, ripped opened and half spilled on the floor.

“What are you doing?” Joe asked.

Mia raised her brows and sucked in her lips.

“Gross. She’s eating cake mix,” Joe said. “Should I take it away from her?”

“I don’t know. What’s the difference if you eat it that way or cooked?”

The boys watched Mia shove fistfuls of cake mix into her mouth and chew it into batter, nearly choking with each swallow. As Mia, surrounded by a halo of yellow powder, finished the last of the mix, the boys lost interest and turned their attention to the video game. Stuffed with bologna and cake batter, Mia wrapped herself in the red flannel and dozed on the couch.

Amber returned with a twenty-four pack of Bud Light. She struggled to slide the case over the threshold into the apartment.

“Hi, Amber,” Brock said, craning his neck in her direction.

“Boys?” Amber dropped her purse on the floor. “A little help?”

Brock tossed the controller and jumped up. Reluctantly, Joe paused their game and rose from the floor. Each boy took one side of the box and carried it into the kitchen. Brock let go of his side and the beer bottles concussed together.

“Careful, jeez. Hey, what is this powder everywhere?” Amber gestured to the yellow ring on the kitchen floor.

“Cake mix,” Joe said.

“Why is it all over the floor?”

“Ask her.” Joe jutted his chin towards Mia.

With cake batter encrusted around her mouth, Mia watched solemnly as Amber groaned and said, “I was going to make you a cake for your birthday.”

“Like over a year ago.”

“I just bought that.”

“No, you didn’t,” Joe said. “You were going to make it for my tenth birthday and I’m eleven and a half.”

Amber did not argue. She yanked open the sliding glass door, slammed it shut behind her, and lit a cigarette. Joe glanced at Mia, and she stared back without expression. He smiled at Mia, not to comfort her, but because he relished the irritation she caused his mother.

“Let’s go,” Joe said to Brock.

Mia followed the boys as they worked on getting the scooter through the doorway.

“She coming with us?” Brock asked Joe, heading down the hall with Mia jogging to stay on their heels.

“Yep.”

“Watch out for Mateo and his brothers,” Brock said. Peeking around the edge of the trailer, Joe watched flashing vehicles fill the parking lot.

“You can’t hide from them forever. You might as well give it back. It’s a piece of shit any ways.”

“It works fine. It’s just a little wobbly.”

In the elevator, Mia picked at the dried cake mix around her mouth.

“Does she talk?” Brock asked. “My little sister talks all the time. I mean, like, all the time, even when she’s alone in her room all by herself. Why doesn’t she have any teeth?”

“I don’t know. I think there’s something wrong with her.”

“Why is her mom in jail?”

“Drugs.”

“Mateo’s mom is in jail too.” Brock rolled the scooter back and forth. “I wonder if they’ll see each other.”

The elevator doors opened and Brock glanced around cautiously before dragging the scooter out. Brock held the front door of the building open and all three stepped out squinting under the bright sun.

Someone shouted, “Get ‘em.”

Joe and Brock broke out into a run. Mia put her hands over her mouth.

“Come on,” Joe yelled at her. Mia looked behind her at the three boys bolting across the parking lot, dodging around cars, towards them. She started to run. Although struggling against the scooter squeaking in tempo with his speed, Brock raced ahead and around the back of the apartment building. Joe cut around the corner, he found Brock lifting the scooter above his head to drop into the dumpster.

“Help me,” Brock said, over his shoulder.

Joe grabbed the handle bars and shoved, and the scooter disappeared over the edge.

Occupying the bottom of the growth chart for eleven-year-old boys at four-foot-one, Brock said, “Now me, push me over.”

Joe linked his fingers together and lobbed Brock into the dumpster. Mia, with bright and wild eyes, barreled towards him as fast as her short legs would take her.

“Come on,” Joe said. “Brock, help me get her over.”

Joe lifted Mia up to Brock and, ungracefully, the two of them fell into the metal box of garbage. Joe climbed the side and jumped in just as the three brothers cleared the corner. Crouched around trash bags and cardboard boxes, the three kids listened to Mateo and his brothers pound by in a flurry of gasping breaths.

“Maybe those idiots will keep running all the way to Iowa,” Brock said.

“They’re a bunch of inbreeds,” Joe said.

“Kinda like this one here.” Brock raised his brows at Mia.

“No shit.”

“Sh.” Brock held up his hand. “I hear them coming back.”

Mia covered her mouth with both fists. The boys’ sneakers slapped against the asphalt around them.

“Hey,” one of the boys shouted. “Look in there.”

“Shit,” Brock said under his breath.

Mia pulled a pink lighter from the pocket of her denim shorts. With both thumbs on the striker wheel, she ignited the lighter. She held down the fuel lever with her thumb and finger and reached for a paper towel tube.

Joe and Brock watched Mia hold the cardboard over the flame. The dry paper flickered and a thin black line of smoke danced wildly, distorting Mia’s face. She waved her wrist back and forth antagonizing the fire.

Mateo and his brothers clambered up the side of the dumpster and yelled, “Gotcha, motherfuckers.”

Joe and Brock kept their eyes stitched to the little fire-starter. She tossed the burning paper tube into the center of the dumpster. All five boys held their breath as the fire leapt across the top of the rubbish.

“Shit,” Brock yelled, moving to escape the sudden heat.

Mateo’s oldest brother yanked Brock out by an arm and a leg.

“Come on,” the other brother screamed at Joe. “Get outta there.”

Joe grasped Mia’s arm. She allowed them to push and pull her limp body out of the dumpster. The flames grew exponentially, rapidly oxidizing the refuse. Joe threw himself over the lip.

Surrounding the dumpster with the blaze reflecting in their eyes, the six children forgot the red scooter feud. The roar of the fire and crackling of plastic, wood, and paper masked the wailing sirens.

“Run,” one of the boys yelled, breaking the through the moment of catatonia, and the kids scattered.

Joe ran away from the burning dumpster and the screaming fire trucks. Sprinting through a small line of trees into the neighboring trailer park, he zig-zagged between mobile homes jumping over yard gnomes and tipped tricycles. He concealed himself between two homes to catch his breath and swallowed against the burning in the back of his throat. As the beat of his heart slowed, his skin began to throb. He twisted his leg around to examine his calf, it was shiny and pink akin to a severe sunburn. Peeking around the edge of the trailer, flashing vehicles filled the parking lot. A commotion of urgent voices and the powerful spray of the water ringing and hissing against the metal dumpster replaced the rage of the fire.

“Mia?” He called out around the other end of the trailer. Weaving through the rows, he ducked behind a tree as a squad car cruised by. He spotted Mia down the hill, naked and pale, standing at the edge of what was generously referred to as the pond of Ridgeview Terrace. Over time, the parking lot run-off water, trapped by cardboard boxes and discarded furniture clogged sewer, created a permanent body of brown, stagnant water.

Joe held tight, rocking foot to foot, waiting for the cop to make a second pass around the lot. Mia bent her knees, swung her arms, and jumped off the edge of the grass into the dirty water.

“Shit.” He ran for it. He imagined pulling Mia’s gray, lifeless body from under the oily black surface and willed his legs to fly down the hill. Splashing into the water, he dropped to his knees and frantically reached around on the slimy bottom. His hands battered against cans and broken glass before he mercifully connected with a warm, soft extremity. He wrenched Mia through the obstinate, dark resistance. As her face broke the surface, her eyes were open wide and she smiled exposing her toothless gums. Her blond hair was plastered across her brow. She coughed streams of colloid water from her mouth and nostrils.

“Jesus,” he yelled at her. “Jesus!”

She flinched between coughs and gasps.

“Don’t do that,” he yelled, tightening his grip on her soft arm. “What the fuck is wrong with you?”

Clumsily, Joe rose to his feet keeping Mia’s head above the water. Holding her under her arms, he staggered towards the edge. He set her down in the grass, dropped down next to her with his elbows on his knees, and wiped the acrid water out of his eyes. She moved closer to him and began to shiver.

“Here.” He reached over and collected her jean shorts and tee shirt. “Put these back on.”

Mia did as she was told and, between intermittent coughs, she delicately manipulated her shirt until it was right-side-out. A curtain of clouds lifted and the sun exposed rainbow shades of bruising on her back and arms. Faded green bruises ringed with a shades of yellow contrasted against the fierce blue and purple bruises. On her head, dark-pigmented lumps shadowed through her wet hair.

Joe raked his fingers through his wet curls. “Why are you even here?”

Mia pulled a fistful of grass out from around her. She examined the smooth green blades before putting them in her mouth.

“Stop. Don’t eat grass. Come on.” Joe stood and lifted Mia into his arms. She was weightless and soft. Wrapping her legs around his waist, she rested her cheek on his shoulder. Joe climbed up the hill, scanned for squad cars, and crossed the parking lot towards the apartment building. The air was sour with the scent of burning refuse.

“Mom?” Joe said, entering the apartment.

There was no answer.

Joe pried Mia off of him and set her down on the kitchen floor. He poured Lucky Charms into a bowl and handed it to her. Lifting the bowl to her lips, she filled her mouth and spilled toasted oats and rainbow-colored marshmallows around her. She plucked cereal off the floor and pressed them through her rosebud lips adding them to her full cheeks. Joe hopped up on the counter, poured himself a bowl, leaned over to the sink and added water. He had long ago forgotten about milk.

The door opened and slammed shut, and Brock raced into the kitchen. His chin was scuffed red against his brown skin. “Can you believe that?” Brock said. “That fire was huge. The cops are everywhere and, lucky for me, they grabbed Mateo’s brother just as he was dragging me out from under a car by my foot.” He held up his scraped palms. “They think he started the fire since he’s already got a record. Is my chin bleeding? It hurts. Can I have some cereal?”

Joe pushed the box of Lucky Charms across the counter.

“Will you pour her some more?” Joe asked Brock. Mia’s eyes had been boring into him since she finished her last marshmallow.

Brock squatted next to where Mia sat on the floor and refilled her bowl. Mia set the bowl on the floor and sifted through the cereal with her fingers.

Brock selected a bowl and spoon from the pile of dirty dishes in the sink. He shook cereal into the bowl, added water, and crammed three spoonfuls of cereal into his mouth. Spitting out cereal, he said, “I had to hide under that car for like an hour. The cops were all over the place. Did you see the size of that fire? We could have burned to death, like dead-dead. She’s crazy. She’s done that before, I betcha.”

Joe watched Mia organize her yellow stars, pink hearts, and purple horseshoes into discrete piles, and eat the blue moons.

“Why are you guys all wet?” Brock asked.

“She decided to go for a swim in the pond, but she can’t swim,” Joe said.

“Gross.”

“Pretty much.”

“Mateo dared me to take a sip of that water once. I said, hell no, but Jackson did it for a cigarette. He ended in the hospital because of it. Remember that? They took his appendix or something out.”

Amber opened the door and stomped into the kitchen. “Have you seen Devon?” She was crying.

“No,” Joe said.

“Hi, Amber,” Brock said, wiping his mouth and smiling at her with gaped teeth.

She glanced at Brock and Mia and turned her attention back to Joe. “He’s not at work. I just went by the construction site and the guys said some woman picked him up. Really, Devon? Really? He’s nowhere to be found and I’m stuck with her,” Amber said, pointing at Mia. “Seriously, this can’t be happening.”

“Did you try calling him?” Joe asked, tilting his bowl to gather the last few bites of cereal.

“Of course, I’ve tried calling him like a hundred times.” Amber wiped her cheek with her sleeve.

There was a change, like a tectonic shift, and Joe set his bowl in the sink. The scent of the fire was replaced by ripe smell of the clogged sink. He noticed his mother’s pink tracksuit stretching across her hips and her stomach pooching over the top of the elastic waistband. Rhinestones missing from both shoulder embellishments created PacMans from the peace signs. “Sorry, Mom,” Joe said absently, examining the newly chiseled lines across her forehead and etched around her eyes.

She stepped back seemingly conscious of his scrutiny.

Brock shook the last of the cereal into his bowl, and said, “Don’t worry, Amber, he’ll probably show up later. He’d be an idiot to leave someone as pretty as you.”

“Well, that cheating son-of-bitch better not show his face around here and she’s definitely not staying here,” Amber said, grabbing at her over-sized imitation purse and rifling around until she fished out her menthol cigarettes. She stuck one between her glossy lips and searched her purse. “Where’s my lighter?”

Brock choked on his Lucky Charms and Joe shot him a look. Amber rummaged through the drawers until she found matches. Standing on the balcony threshold with the door open, she lit a cigarette, and thought out loud, “We’ll drive her over to her mom’s house.”

“I thought her mom was in jail?” Brock said. “For drugs? Right, Joe?”

“She’s got a few other kids.” Amber flicked her cigarette ash over the edge. “Someone must be there looking after them.”

Amber led the mission to her Buick Sedan followed by Joe, Brock, and Mia. Amber still referred to the Buick as Grandma’s car because it was handed down to her after her grandmother died six years ago. Amber’s parents signed the title over to her believing her lack of transportation was holding her back, when they still had hope for her future, but now Joe reads the disappointment on their faces at every Christmas Eve dinner.

“Joe, will you sit in the back with her and keep her down?” Amber asked, unlocking the door with the key. “I’m not getting a ticket, because of her and that carseat law.”

Brock’s face lit up. “I’ll sit in front with you.”

Joe opened the door, but Mia made no move to get in the back seat .

“Come on,” Joe said, gesturing into the vehicle.

Mia remained still.

Amber turned around from the driver’s seat. “What now?”

“Nothing,” Joe said, and held out his hand to Mia.

Mia placed her hand in Joe’s palm and he guided her into the backseat. He climbed in next to her, and Mia scooted closer to him pressing her entire leg next to his thigh. He wanted to move away, but her warm skin exerted an irresistible gravitational pull. She seemed even smaller and more vulnerable in the expanse of the back seat. Amber, as always, drove while she texted and made calls.

“Call Rebecca,” Amber robotically demanded of her phone. “Mobile.”

Amber bitched to Rebecca about Devon’s lies and his miserable, creepy daughter. The conversation with Rebecca, including details of her intimacies with Devon, enthralled Brock. Brock listened and nodded along sympathetically as if Amber was having an exclusive conversation with only him. Mia strained her neck to look out the back window.

“Keep her down,” Amber said to Joe through the rearview mirror.

Joe amused Mia with illusions of removing his fingers at the knuckle and pulling a quarter he found on the floor out of her ear. Tricks he had acquired over the years from a variety of men instructed to entertain him.

Amber pulled the Buick in front of a tired two-story house with chipped yellow paint, and rebounded off the curb twice before she shifted the vehicle in park. Into her phone, she said, “I gotta go. I’m here.”

“Come on,” she said to Mia. “Out of the car.”

Mia squeezed against Joe.

Amber yanked open the back door. “Come on. Move it.”

Mia made no move to exit, and Amber said, “Joe, can you help me out here?”

Joe lifted Mia onto his lap and maneuvered out of the back seat. Mia wriggled herself around and clung onto him. “I’ll come with,” he said.

Amber and Joe, with Mia wrapped around him, walked up the weed-riddled sidewalk and cement steps. The ripped screen door was open about an inch.

Amber knocked on the wood frame and it banged against the jamb. “Hello?” she yelled into the house with urgency.

A child with a blond afro wearing purple corduroy coveralls appeared in the doorway. He or she carried a sippy cup upside down.

“Is your mama here?” Amber asked.

The blinking child did not move, but the cup steadily dripped onto the floor.

“Hello?” Amber tried again louder. “Anyone home?”

“Coming,” a voice returned. “Hold your horses, I’m coming.”

Mia pulled her face from Joe’s shoulder and turned towards the voice resonating from inside the house. A heavyset black woman with gray hair pulled into a tight bun came to the door. She squinted at Amber, and when she saw Mia, she held her hands up and said, “Oh no. That one is not mine. No way, uh uh.”

“But she—“

“Hi, sweetheart,” the woman addressed Mia before she continued her protests against Amber. “I said, no.”

“But she’s the sister, or at least half-sister, of that one,” Amber said, pointing down at the amber-eyed child smiling at Mia.

“I’m looking after mine, and that one is not mine,” the woman said, nodding and winking at Mia. “I’m sorry, but I gots my hands full with the three boys here.”

“That one is not mine,” Amber said, thumbing at Brock’s brown face watching from the passenger seat of the Buick. “But I’m looking after him.”

“That’s your own business.”

“This one belongs here. This is her mama’s house,” Amber said, and tried to pull Mia off of Joe.

“Girl, if you put that child down, I will open this door and come outside, and you do not want me to open this door and come outside. This here is my house. Her mama is not coming back for a long while this time, and that little girl got her own daddy to look after her.”

Amber stopped yanking on Mia and turned back towards the formidable woman behind the screen. “Well, he’s gone off with somebody else. What am I supposed to do with her?”

“I don’t know, but she is not coming back into this house. I got three grandbabies of my own in here and I am too old to keep up with them as it is.”

Amber rubbed her forehead with the heels of her hands and groaned before marching back towards the car.

The woman smiled sympathetically at Joe and said, “I’m real sorry I can’t help ya’ll.”

Joe shrugged and said, “Have a good day.”

“You too, son.”

Joe followed his mother back to the Buick. From the corner of his eye, he saw Mia waving with her fingers at the woman and child in the house. Joe climbed in the back with Mia while Amber stood outside the car smoking, pacing, and yelling into her phone.

“So?” Brock asked.

“She’s not staying here anymore. I guess this is the wrong grandma,” Joe said.

“Aliyah’s grandma and grandpa don’t like me much either,” Brock offered, referring to his half-sister’s father’s parents. “They spoil her rotten. That’s why she’s such a brat.”

Amber threw her cigarette butt into the woman’s yard. She got into the car, and said, “I have an idea.” She held up her phone as the British-accented automated voice asked how it could help her, and, she answered, “Directions to the nearest daycare.”

The phone instructed her to take a few left turns and then a few right turns until they arrived in front a beige rambler with a homemade sign in the front yard incorrectly spelling out, Lisenced Daycare.

“What’s your plan?” Joe asked. “Just drop her off?”

“Exactly. Let them figure out what to do with her,” Amber said. “Come on.”

“Want me to do anything, Amber?” Brock asked.

“No.” Amber scrambled out of the car. “Stay here.”

Amber jogged up the front sidewalk. Joe followed with Mia wrapped around his neck.

Amber rang the doorbell, a dog barked, and she said, “Follow my lead.”

Only a few seconds passed before Amber rung the bell again.

“Jesus, mom.”

“What?”

The door opened and a woman, surrounded by six children of varying heights, wiping her hands on a dishtowel, asked, “Yeah?”

“Good afternoon,” Amber said over the agitated beagle. “I’m looking for a quality daycare for my daughter.”

“Oh, I can’t. I’m at the maximum right now.”

“The sign in your yard led me to believe that you are available to care for children.”

The woman’s gaze moved past Amber towards the sign as if she was surprised it was still there.

“So, can you take her?”

“I’m sorry,” the woman backed up and started to close the door.

“Wait,” Amber said. “Please, if you could just make an exception for today, I’ll pick her up in a few hours.” Amber started to cry. “It’s just that my mother’s in the hospital and they won’t let children under ten-years-old into the intensive care unit.”

The woman eyed Joe who turned away in humiliation over his mother’s histrionics.

“Listen, I’ve got a family to feed and can’t afford to lose my business. I don’t know what you’re up too, but if you don’t get off my property, I’ll call the police,” the woman said, and herded the children behind her before she closed the door and clicked the chain into place.

“What the fuck?” Amber yelled and kicked the door with her pink sequined flip-flop. “What kind of bullshit place are you operating here? Goddammit, I broke my toe.”

“Come on, mom,” Joe said, and walked back towards the Buick.

Amber, shedding genuine tears, limped across the yard towards the misspelled sign. Pulling the wooden sign from the ground, she curb stomped it into pieces.

“Brock, roll up the windows.” Joe said, climbing into the back seat with Mia. “I hate when she gets like this.”

“I can’t. The car isn’t on,” Brock said.

“Turn it on.”

“I can’t. I don’t have a driver’s license.”

“You don’t need a driver’s license to start the car to roll up the windows.”

“Yes, I think you do.”

“Forget it.”

“Here comes a cop,” Brock said, looking over Joe out the back window.

Joe stuck his head out the window and yelled, “Mom! Cops!”

Amber kicked the remains of the broken sign into the street and hobbled to the car. She jumped in the front seat, pumped the accelerator three times, and cranked the ignition. The old Buick revved to life. Slamming the transmission into drive, she sprayed gravel peeling away from the daycare.

“That was close,” she said, eying her rearview mirror and speedometer. “Keep her down.”

“She’s on the floor,” Joe said.

“Great, keep her there.”

The sun inched towards the horizon and graduated from yellow to orange. Brock lowered the visor to block the sun and inspected his raw chin in the mirror. Amber, winding and unwinding a loose strand of hair around her finger, drove in silence, before she gripped the wheel, pressed down on the accelerator, and said, “Let’s stop at the grocery store.”

They pulled into a parking lot of a large grocery store chain and walked in under the scrutiny of the fluorescent lights. The air conditioned store caused Joe’s skin to goose bump, irritating his burned calves. Amber yanked a cart free from the corral. The kids followed her as she limped up and down the aisles thoughtlessly added items. Mia picked up a four-pack of Jello cups and glanced at Amber for approval. Receiving no acknowledgment, she pressed the package to her chest before placing it back on the shelf. Brock slipped a Hershey’s Chocolate Bar into his waist band. They meandered down an aisle with a small section of dog and cat supplies. A basket filled with plush toys for dogs distracted Mia. Picking through the basket, she hugged a pink fuzzy pig to her chest. She grabbed a squeaky frog, chirped it repeatedly, and held it up for Joe to see. He nodded.

“Pick out your favorite one, honey,” Amber said.

Mia grinned a gummy smile at Amber. She stuck her arms deep into the basket and scooped dog toys onto the epoxy floor. Beginning a system of sorting, Mia assessed one toy at a time before setting it in a pile designated by color. Amber released the cart, stepped back, and whispered, “Okay, let’s go.”

“Mom?” Joe said, holding his palms out helplessly.

“Come on,” Amber said. “These stores have protocols to deal with missing kids.”

Joe choked for air.

Amber took Brock’s hand, walked away from Mia, and looked back over her shoulder at Joe and said, “Come on.”

“Mom? You’re going to dump her here? Alone?” Joe asked, his voice cracking into a higher octave.

Amber turned away and pulled Brock along with her.

Despite his protests, his feet obediently followed his mother down the aisle. Trailing behind her, he scowled at his mother’s frizzy bleached hair and the way she walked on the insides of her cracked heels. He flinched with each slap of her glittery flip flops.

Joe walked out of the grocery store without Mia. For the rest of Joe’s life, he was haunted by the voice of the silent little girl.

BIO

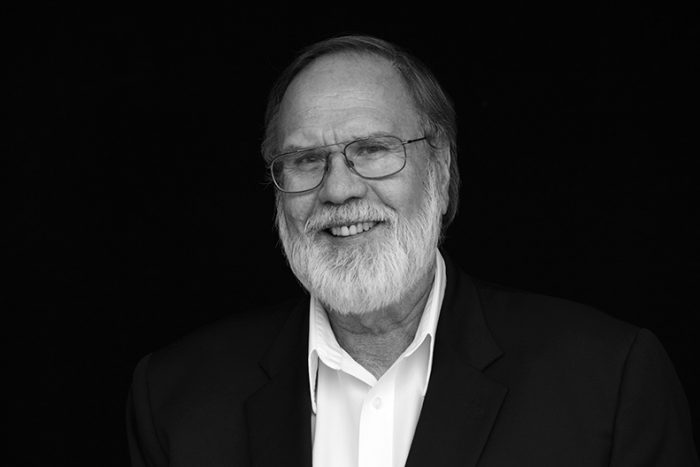

Paisley Kauffmann lives and writes in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Life provides her with millions of bits and pieces to stitch together into stories. Her short stories have been published in The Talking Stick and The Birds We Piled Loosely. She writes with one of two pugs in her lap and receives gracious feedback from her husband. The Loft Literary Center, the Minnesota writing community, and her writing group support and fuel her motivation.

Paisley Kauffmann lives and writes in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Life provides her with millions of bits and pieces to stitch together into stories. Her short stories have been published in The Talking Stick and The Birds We Piled Loosely. She writes with one of two pugs in her lap and receives gracious feedback from her husband. The Loft Literary Center, the Minnesota writing community, and her writing group support and fuel her motivation.

Martin Keaveney has been widely published in Ireland, the UK and the US. Fiction, Poetry and Flash may be found at Crannog (IRL), The Crazy Oik (UK) and Burning Word (US) among many others. He has a B.A. and M.A. in English and is currently a PhD. candidate at NUIG.

Martin Keaveney has been widely published in Ireland, the UK and the US. Fiction, Poetry and Flash may be found at Crannog (IRL), The Crazy Oik (UK) and Burning Word (US) among many others. He has a B.A. and M.A. in English and is currently a PhD. candidate at NUIG.

M. F. McAuliffe is co-author of the poetry collection Fighting Monsters (Melbourne, 1998), & the limited-edition artist’s book Golems Waiting Redux (Portland, 2011). Her novella, Seattle, was published in 2015; her collection, The Crucifixes and Other Friday Poems, will be published this fall.

M. F. McAuliffe is co-author of the poetry collection Fighting Monsters (Melbourne, 1998), & the limited-edition artist’s book Golems Waiting Redux (Portland, 2011). Her novella, Seattle, was published in 2015; her collection, The Crucifixes and Other Friday Poems, will be published this fall.

Christina Bavone is a teacher and writer of fiction and poetry. She currently teaches writing at National Louis University. She holds a Bachelors in writing from Columbia College and a Masters in teaching from National Louis University. She is currently pursuing a Masters in English at University of Illinois at Chicago as a part of their Program for Writers. She has published poems in online lit mag Ophelia Street and international publication Every Second Sunday. In addition to teaching and writing, Christina is mother to a boisterous 4-year-old.

Christina Bavone is a teacher and writer of fiction and poetry. She currently teaches writing at National Louis University. She holds a Bachelors in writing from Columbia College and a Masters in teaching from National Louis University. She is currently pursuing a Masters in English at University of Illinois at Chicago as a part of their Program for Writers. She has published poems in online lit mag Ophelia Street and international publication Every Second Sunday. In addition to teaching and writing, Christina is mother to a boisterous 4-year-old.

Stephanie Renae Johnson is the Editor-in-Chief of The Passed Note, a lit mag for young adult readers by adult writers. She is also a recent graduate of Lenoir-Rhyne University’s Master of Arts in Writing program and has just finished her first book of poetry. Her work has been published by Parenthetical and Penny, among others. She was a finalist for the 2016 Claire Keyes poetry award, judged by the award winning poet Ross Gay. She lives in Asheville, North Carolina, with her fiancé and their seven bookshelves.

Stephanie Renae Johnson is the Editor-in-Chief of The Passed Note, a lit mag for young adult readers by adult writers. She is also a recent graduate of Lenoir-Rhyne University’s Master of Arts in Writing program and has just finished her first book of poetry. Her work has been published by Parenthetical and Penny, among others. She was a finalist for the 2016 Claire Keyes poetry award, judged by the award winning poet Ross Gay. She lives in Asheville, North Carolina, with her fiancé and their seven bookshelves.

Shay Siegel is from Long Island, New York. She received a B.A. in English from Tulane University in New Orleans where she was a member of the Women’s Tennis Team. She recently completed an MFA in Fiction at Sarah Lawrence College. Her writing has appeared in The Montreal Review, Burning Word, Mouse Tales Press, The Cat’s Meow for Writers and Readers, The Rusty Nail Literary Magazine, Belleville Park Pages, Black Heart Magazine and Extract(s). Her website is

Shay Siegel is from Long Island, New York. She received a B.A. in English from Tulane University in New Orleans where she was a member of the Women’s Tennis Team. She recently completed an MFA in Fiction at Sarah Lawrence College. Her writing has appeared in The Montreal Review, Burning Word, Mouse Tales Press, The Cat’s Meow for Writers and Readers, The Rusty Nail Literary Magazine, Belleville Park Pages, Black Heart Magazine and Extract(s). Her website is

My illustrations are primarily rendered in pen and ink on paper. I am inspired by strong, trailblazing, bad-ass women who push boundaries, forge their own paths, and define for themselves what it means to achieve success. I am also inspired by the take-no-shit attitude of the ’90s and transformative self-expression made possible through art, poetry and music.

My illustrations are primarily rendered in pen and ink on paper. I am inspired by strong, trailblazing, bad-ass women who push boundaries, forge their own paths, and define for themselves what it means to achieve success. I am also inspired by the take-no-shit attitude of the ’90s and transformative self-expression made possible through art, poetry and music.

Janet Buck is a seven-time Pushcart Nominee and the author of four full-length collections of poetry. More than 4,000 of her poems & pieces of prose are in print and on the internet. Janet’s recent work has appeared in The Birmingham Arts Journal, Antiphon, Offcourse, PoetryBay, Vine Leaves, Poetrysuperhighway, Misfit Magazine, Lavender Wolves, and River Babble. Her latest print collection of verse, Dirty Laundry, is currently available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble & other outlets. Visit the ordering link at her new web page:

Janet Buck is a seven-time Pushcart Nominee and the author of four full-length collections of poetry. More than 4,000 of her poems & pieces of prose are in print and on the internet. Janet’s recent work has appeared in The Birmingham Arts Journal, Antiphon, Offcourse, PoetryBay, Vine Leaves, Poetrysuperhighway, Misfit Magazine, Lavender Wolves, and River Babble. Her latest print collection of verse, Dirty Laundry, is currently available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble & other outlets. Visit the ordering link at her new web page:

A Pushcart nominee, Lana Bella is the author of two chapbooks, Under My Dark (Crisis Chronicles Press, 2016) and Adagio (forthcoming from Finishing Line Press). She has had her poetry and fiction featured in over 200 journals including Columbia Journal, Poetry Salzburg Review, and Third Wednesday, among others. She resides in the U.S. and the coastal town of Nha Trang, Vietnam, where she is a mom to two far-too-clever frolicsome imps.

A Pushcart nominee, Lana Bella is the author of two chapbooks, Under My Dark (Crisis Chronicles Press, 2016) and Adagio (forthcoming from Finishing Line Press). She has had her poetry and fiction featured in over 200 journals including Columbia Journal, Poetry Salzburg Review, and Third Wednesday, among others. She resides in the U.S. and the coastal town of Nha Trang, Vietnam, where she is a mom to two far-too-clever frolicsome imps.

Robert Boucheron is an architect in Charlottesville, Virginia. His short stories, essays and book reviews appear in Bangalore Review, Digital Americana, Fiction International, New Haven Review, North Dakota Quarterly, Poydras Review, Short Fiction, The Tishman Review.

Robert Boucheron is an architect in Charlottesville, Virginia. His short stories, essays and book reviews appear in Bangalore Review, Digital Americana, Fiction International, New Haven Review, North Dakota Quarterly, Poydras Review, Short Fiction, The Tishman Review.

Ashley Inguanta is a small-press author, photographer, and yoga teacher who has dedicated her life to helping others heal by developing healthy coping mechanisms. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing from The University of Central Florida in 2011, and she earned her 200 hour RYT certificate from YOGAMAYA New York in 2014. She is the author of The Way Home (Dancing Girl Press, 2013 / re-published with The Writing Disorder on Kindle), For the Woman Alone (Ampersand Books 2014), and Bomb, which is forthcoming with Ampersand Books this fall. As a mental health advocate and queer rights advocate, she’s volunteered with organizations and facilities like Equality Florida and Lakeside Alternative, and currently she teaches healing, restorative writing and yoga classes at several locations in Central Florida.

Ashley Inguanta is a small-press author, photographer, and yoga teacher who has dedicated her life to helping others heal by developing healthy coping mechanisms. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing from The University of Central Florida in 2011, and she earned her 200 hour RYT certificate from YOGAMAYA New York in 2014. She is the author of The Way Home (Dancing Girl Press, 2013 / re-published with The Writing Disorder on Kindle), For the Woman Alone (Ampersand Books 2014), and Bomb, which is forthcoming with Ampersand Books this fall. As a mental health advocate and queer rights advocate, she’s volunteered with organizations and facilities like Equality Florida and Lakeside Alternative, and currently she teaches healing, restorative writing and yoga classes at several locations in Central Florida.

Tom W. Miller lives an ordinary life yet finds insight and entertainment from his everyday experiences. He has published a previous story in Red Fez and lives in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley with his family.

Tom W. Miller lives an ordinary life yet finds insight and entertainment from his everyday experiences. He has published a previous story in Red Fez and lives in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley with his family.

Ruby Cowling is a British writer currently living in London. Her work has won awards that include, The White Review Short Story Prize and the London Short Story Prize, and has been shortlisted in contests from Glimmer Train, Short Fiction, and Aesthetica, among others. Recent anthology credits include I Am Because You Are (a Freight Books collection of work inspired by the theory of General Relativity); Flamingo Land and Other Stories, from Flight Press; and Unreal City: Constructing the Capital, a book of fiction and non-fiction about London, from Cours de Poétique.

Ruby Cowling is a British writer currently living in London. Her work has won awards that include, The White Review Short Story Prize and the London Short Story Prize, and has been shortlisted in contests from Glimmer Train, Short Fiction, and Aesthetica, among others. Recent anthology credits include I Am Because You Are (a Freight Books collection of work inspired by the theory of General Relativity); Flamingo Land and Other Stories, from Flight Press; and Unreal City: Constructing the Capital, a book of fiction and non-fiction about London, from Cours de Poétique.

Jennifer Elizabeth Johnson has a BA in sociology, studied creative writing at Austin Community College. She currently lives in Newark, New Jersey. She’s lived in five countries and is a cinephile who believes that dubbing movies in another language is a grave crime against art. She wishes Bernie Sanders was her father.

Jennifer Elizabeth Johnson has a BA in sociology, studied creative writing at Austin Community College. She currently lives in Newark, New Jersey. She’s lived in five countries and is a cinephile who believes that dubbing movies in another language is a grave crime against art. She wishes Bernie Sanders was her father.

Janet Hope Damaske is a stay-at-home mother with interests in writing, reading, editing and psychology. After earning her BA in psychology with a minor in creative writing at Hamilton College, she worked for several years at a rehabilitation center for people with mental illness, providing job training and running a writer’s group for creative therapy. She later moved onto a career in medical publishing, where she continues to work part-time. Janet currently volunteers with several non-profit organizations in her hometown of Winchester MA, where she lives with her husband and two children. She writes a blog, which can be found at

Janet Hope Damaske is a stay-at-home mother with interests in writing, reading, editing and psychology. After earning her BA in psychology with a minor in creative writing at Hamilton College, she worked for several years at a rehabilitation center for people with mental illness, providing job training and running a writer’s group for creative therapy. She later moved onto a career in medical publishing, where she continues to work part-time. Janet currently volunteers with several non-profit organizations in her hometown of Winchester MA, where she lives with her husband and two children. She writes a blog, which can be found at

D.G. Geis lives in Houston, Texas. He has an undergraduate degree in English Literature from the University of Houston and a graduate degree in Philosophy from California State University. His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Fjords, Memoryhouse, 491 Magazine, Lost Coast, Blue Bonnet Review, The Broadkill Review, A Quiet Courage, SoftBlow International Poetry Journal, Blinders, Burningword Literary Journal, Poetry Scotland (Open Mouse), Crosswinds, Scarlet Leaf, Zingara, Sweet Tree, Atrocity Exhibition, Driftwood Press, Tamsen, Rat’s Ass, Bad Acid, Crack the Spine, Collapsar, Grub Street, Slippery Elm, Ricochet, The Write Place at the Write Time, Steam Ticket, Razor, Origami, Matador, Cheat River, Euphemism, Two Cities, The Hartskill Review, Sugar House, Literary Orphans, Dash, Zabaan, Clare, Panoplyzine, Boston Accent, Silkworm, Drylandlit, Permafrost, Gingerbread House, and The Machinery. He will be featured in a forthcoming Tupelo Press anthology of 9 New Poets and is winner of Blue Bonnet Review’s Fall 2015 Poetry Contest. He is also a finalist for both The New Alchemy and Fish Prizes (Ireland).

D.G. Geis lives in Houston, Texas. He has an undergraduate degree in English Literature from the University of Houston and a graduate degree in Philosophy from California State University. His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Fjords, Memoryhouse, 491 Magazine, Lost Coast, Blue Bonnet Review, The Broadkill Review, A Quiet Courage, SoftBlow International Poetry Journal, Blinders, Burningword Literary Journal, Poetry Scotland (Open Mouse), Crosswinds, Scarlet Leaf, Zingara, Sweet Tree, Atrocity Exhibition, Driftwood Press, Tamsen, Rat’s Ass, Bad Acid, Crack the Spine, Collapsar, Grub Street, Slippery Elm, Ricochet, The Write Place at the Write Time, Steam Ticket, Razor, Origami, Matador, Cheat River, Euphemism, Two Cities, The Hartskill Review, Sugar House, Literary Orphans, Dash, Zabaan, Clare, Panoplyzine, Boston Accent, Silkworm, Drylandlit, Permafrost, Gingerbread House, and The Machinery. He will be featured in a forthcoming Tupelo Press anthology of 9 New Poets and is winner of Blue Bonnet Review’s Fall 2015 Poetry Contest. He is also a finalist for both The New Alchemy and Fish Prizes (Ireland).

Paisley Kauffmann lives and writes in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Life provides her with millions of bits and pieces to stitch together into stories. Her short stories have been published in The Talking Stick and The Birds We Piled Loosely. She writes with one of two pugs in her lap and receives gracious feedback from her husband. The Loft Literary Center, the Minnesota writing community, and her writing group support and fuel her motivation.

Paisley Kauffmann lives and writes in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Life provides her with millions of bits and pieces to stitch together into stories. Her short stories have been published in The Talking Stick and The Birds We Piled Loosely. She writes with one of two pugs in her lap and receives gracious feedback from her husband. The Loft Literary Center, the Minnesota writing community, and her writing group support and fuel her motivation.

Claire Tollefsrud is an undergraduate student working on a double major in Psychology and Creative Writing. Storytelling has always been a passion of hers. She also enjoys Tae Kwon Do, singing, and going on small, everyday adventures.

Claire Tollefsrud is an undergraduate student working on a double major in Psychology and Creative Writing. Storytelling has always been a passion of hers. She also enjoys Tae Kwon Do, singing, and going on small, everyday adventures.

Bethany W. Pope is an award-winning writer. She received her PhD from Aberystwyth University’s Creative Writing program, and her MA from the University of Wales Trinity St David. She has published several collections of poetry: A Radiance (Cultured Llama, 2012) Crown of Thorns,(Oneiros Books, 2013), The Gospel of Flies (Writing Knights Press 2014), and Undisturbed Circles(Lapwing, 2014). Her collection The Rag and Boneyard, shall be published soon by Indigo Dreams and her chapbook Among The White Roots Will be released by Three Drops Press next autumn. Her first novel, Masque, shall be published by Seren in 2016.

Bethany W. Pope is an award-winning writer. She received her PhD from Aberystwyth University’s Creative Writing program, and her MA from the University of Wales Trinity St David. She has published several collections of poetry: A Radiance (Cultured Llama, 2012) Crown of Thorns,(Oneiros Books, 2013), The Gospel of Flies (Writing Knights Press 2014), and Undisturbed Circles(Lapwing, 2014). Her collection The Rag and Boneyard, shall be published soon by Indigo Dreams and her chapbook Among The White Roots Will be released by Three Drops Press next autumn. Her first novel, Masque, shall be published by Seren in 2016.