i, Clouded

by T.E. Winningham

Pardon for those who died despairing; hope for those who died unhoping;

good tidings for those who died stifled by unrelieved calamities.

On errands of life, these letters speed to death.

– Herman Melville

The Company put us way out in the frigging sticks, tripled-up in the cheapest ratty room nowhere near the campus, off the wrong expressway even, in these cornfields stretching must be hundreds of miles in every direction. Nick, Tracy, and me. Checking into the motel we could see it, the campus, standing up from the flat horizon the way state universities make bubbles out of the void like sealed ecosystems. Standing there with shirttails flapping in the wind, a nervous twitch started in my eyelid waiting for the GPS to find us, shock and horror settled in my stomach when it gave up. Walked across the gravel lot in the heat, from the motel to the dust caked gas station where the greasy-fingernailed attendant sold me an actual—never to be folded correctly back to its original shape—paper roadmap. In the room we sat around it at the table in Nick’s cigarette smoke and stale lamplight, marking in pencil. The route of county roads leading from our We Are Here dot to the We Need to Get Here Every Damned Morning dot traced the shape of a lost Tetris game. Then we turned off the lamp and lay listening to flies trapped between the window and screen, stripped down to underwear and sweating, thinking this is only April.

The library sat square in the center of campus, towering over the stone-columned museumesque buildings and surrounding lawns. Students on foot and bicycle made a kind of swirling vortex around it, a hurricane’s empty center. The first morning we introduced ourselves to the head reference librarian, a small woman with a thick Slovenian accent and papers prepared for us. Call numbers by floor, tutorials for the online card catalogue. Unexpected, really, as this was merely a formality but nevertheless she led us under the arched marble and stained glass of the lobby to an echo chamber of a vacant reading room and sat us down at the first of the long mahogany tables. “You will find the book stack very well ordered,” she said, passing out the stapled pages. “In spite of this area being originally closed to the students.”

“Closed?” Tracy asked.

“Yes. The students needed only to bring call numbers of the books they desired to the front desk. An attendant would then return with them. This changed quite some time ago, problems with the staff and with budgets, but we have worked diligently to reorder the entire stack to make it accessible to the students. Who are not often accustomed to library methods.

“Now,” she continued, and began reading deliberately from the handout. The numbers and decimals and cross-referenced charts were incomprehensible to me. Nick exhaled loudly as he flipped ahead through the pages.

“Ma’am, I’m sorry to interrupt,” Nick stood, “but we need to get started. Waivers we’ll sign, as our Company agreed, but the rest of this, it isn’t how we work.”

“But you will not know where to find the books you are looking for.”

He pointed to the bookstack entrance, a small doorway behind the librarian’s desk, smiling. “They’re in there. We just start at one end and work our way to the other, Company policy. Anyway, with searchable text we’re basically making catalogues obsolete.”

She gasped; we all stood.

“Thank you for your time, we’ll let you know if we need anything,” I said as we left her just standing there and walked into the stacks.

We were scanning twelve hours a day, driving back and forth on the dark two-lanes with drunk pickup drivers, suicidal raccoons, and teens standing on parked cars shooting rifles at God knows rustling in the fields. In the mornings, still dark, the same minus the kids on the abandoned cars. Mists hung low like a ceiling over the corn stalks to either side, long gray nightmare tunnels in the headlights, breath and coffee steaming over the windshield and Nick’s cigarette ash floating up from the backseat. And Tracy, asleep, head bouncing against the passenger window with the smearing noise of skin on wet glass. Three weeks and we were zombified.

In the motel Tracy got her own bed, tiny and swimming in her flowery pajamas, hornrimmed glasses pushed up as a headband holding red bangs from her face. The paintings hanging around us made me think of some Bob Ross assembly line sweatshop, rows of easels and brushes twitching furiously, making the trees happy or else. Past midnight and the TV options are softcore porn and an advertisement for this new acne-busting home laser system, and between the two it’s hard to tell which paid actors are more excited. Tracy clicks back and forth and decides on porn. Nick sleeps next to me, mumbling something about focused light and ray guns. “Bart,” Tracy rolls onto her side to face me. “We haven’t slept in a week. This has to change.” On her wrist is a tattoo of a band-aid and scissors, a kind of warning against permanent mistakes. Hers is the personality that disappears under sackcloth dresses, the Company simply forgets her, she’s quiet and acquiescent-seeming with authorities and they don’t understand irony. “Hey there, Nickers, wake up! We’re formulating a plan.”

Nick snorts or coughs or just something wet catches in his throat.

Tracy takes pen and pad of paper from the drawer with the Bible. Tearing sheets off the pad, she throws them in our direction and they swirl like snowflakes between the beds. “Y or N to the commute,” she says.

“What’s our alternative?”

“Either a Y or an N.” She mutes the moaning TV.

“I mean, if we don’t commute then what?”

“We’re checked in indefinitely,” Nick’s awake. “We stay here.”

Tracy writes on one of the sheets. “I’ll mark that as Abstained.”

“It’s not…” Nick sits up, “it’s clearly an N. Or, wait,” he looks to me.

“Oh good, settled then.”

“You mean Y, Nick,” I hand him a slip of paper. “As in: yes we commute.”

“Too late,” Tracy folds three sheets in her lap. “We’re in unanimous, resounding agreement.”

###

We moved into the library at the end of Finals Week when the building’s mostly a ghost town. The lights go off predictably at night and flicker back on in their little metal cages in the morning. Important administrative things are surely going on elsewhere, though I can’t imagine what they are. But the stacks are quiet. We’re contracted with the university to be here “until we’re done” scanning and the Company made it very clear they don’t care to hear from us until then. Assuming we haven’t all died and rotted first. We left the rental car parked next to a dumpster behind off-campus housing and set up camp in the Medieval French Poetry section, confident we won’t be discovered. Sleeping bags, two flashlights, lots of bottled water and energy bars, pizza delivery on speed dial along with obviously plenty to read. The twelve hour days continue, down on the bottom floor where we started, still, eventually working our way up. We’re already chilled in the unbelievable air conditioning fanning constantly from the vents, sitting alone in our aisles scanning page after page until the lights go out and feeling our way back to camp.

There was at one time a plan for this building, you can tell, but it’s long forgotten. The aisles stretch sometimes forever while others end abruptly against support columns, plastered with yellowed signs taped over each other with call numbers and arrows pointing left or right in the dead ends. The fire sprinkler plumbing and electrical conduits run exposed overhead, the casings for power outlets often hanging empty next to bundles of the multi-colored wires of a newer system. Reflective tape traces paths along the floor where it’s swept clean from the elevators to freshly painted shelves, everything near the stairwells is decaying and dirty. I can only imagine the asbestos waiting to ooze down over us from the cracked HVAC and hot water pipes.

This kind of isolation, of sensory deprivation, of course we’re all going a little insane getting used to it.

Nick reminds me of a woman in drag if she overdid the five o’clock shadow and greased a pompadour to its natural limits, he’s from the East coast and I’m telling myself he was going to crack under Company pressure anyway. He started talking about himself in the 3rd person but weirdly, as if relaying messages to all three of us from some fourth, boss-type person coincidentally named Nick. Like, Nick wants us to work American Literature, 1937-38 today. Or, Nick has an updated completion timetable for us. The orders come down without discernable pattern, and the random changes totally screw us up. Tracy usually shakes in place for a second before saying for example Who fucking promoted Nick? and running off down the aisles. She’s right, too, he’s not in charge—just a little older. I like playing along but this invisible Nick can be a humorless ass. I asked him once if we could take lunch outside for a change and all he said was No, no, Nick doesn’t think that’s a good idea, Bart. Then, In fact, Bart, Nick has cancelled lunch breaks.

Which is really too bad, because this job is boring. Imagine scanning book pages with a handheld gizmo for a living. It’s pretty much the same as holding an extremely docile cat in your lap and brushing it until well after your arm goes numb, then putting it back on the shelf and taking the next cat, then the next, over and over for thousands of hours. The detritus and wisdom, conquests and failures of the world shelved to the ceiling around us. Most of it. Or at least part of it, there’s no way for us to know: for time’s sake, Company policy forbids reading. But I feel the shelves looming so impossibly high, even as I thunk my head on a fire sprinkler standing up. I’ve scanned more pages than I can count, haven’t seen the sun in longer than I’ll admit, and I’m freezing. There are no windows here, no clocks. No floor marked G and I know the one marked 1 isn’t but forget which one is. We take elevators in both directions, stepping off it seems always into basements.

“It’s worth it,” Nick says, “for the future.” Marking the place in his book, he stands. “We think of libraries as social institutions, as a common good, but the building is just a warehouse. An antiquated system. Indexes, catalogues, all that’s gone now. Our warehouse is virtual. And with tags and searchable keywords it’s the end of systems.” He gets that Rally-the-Troops look. “We’re consolidating the network, and once we’re finished this never has to be repeated. This,” raising the book at us, “I could throw this anywhere because we’ll never need to find it again. It’s in the Cloud now. We’re getting rid of old ideas of organization because they’re holding us back like a dead weight, like hobbling a horse.”

“Very eloquent,” Tracy says, checking her email.

Nick looks at the phone in her hand. “By the way, Nick doesn’t want us using our mobile devices anymore. He feels they’re distracting us from our work and so, as of tomorrow, he’s cancelling our internet access. If you want to update your away message, now would be a good time.”

Tracy looks up at him, eyes almost murderous or dead. She opens her mouth to speak but closes it again, looks at me. She stands and walks off and we don’t see her for the rest of the day.

Sanity took a turn for the worse without the internet. There is not a thing left to do but scan, and the constant, endless enormity of it all is crushing. The web becomes a phantom limb, a displaced itch or a tapping on my shoulder for attention. It’s there, I feel it there, but our connection only goes one way now through the scanners: up, out, away into the Cloud.

So for something to break up the day I make lists of new Company slogans, things like Feed the Cloud and We’ll Read For You. I like the Cloud. As abstractions go it’s a good one. An ether-land all around us tethered to a few black boxes, no one knows where, with some demonic genies inside throwing switches and pulling levers, moving little 1s and 0s across magnetic disks buried anonymously in a desert. But it’s a hungry Cloud. It’ll fill the sky and not be filled, though we try—offering what we can, books, pictures and tags, names and where we are, mapping every moment so it can learn. Still it demands more, everything and all of it in three dimensions. And so on the title pages of books I write, very faintly in pencil, The Cloud thanks you for your devotion to its Mission.

Tracy barricaded herself behind a luggage fort and gets up in the middle of the night. I hear her unzip out of her sleeping bag and creep off down the aisles. At first I only followed to the stairwell, it’s so cramped in there with the low zigzagged flights of echoing metal steps she’d hear me instantly. But I grabbed the door as it slammed, before the latch caught, and stood listening and watching for the flashlight beam above and counting her steps rising up and around and up. I figured she’d gone to fifteen and the next night waited until long after she’d left camp, went up there and walked toward the dim light far off in a corner, the smell of mildew and cardboard in the air and the sound only a typewriter makes clacking through the dark. She’s at it for hours each night. Floors below, I lie awake listening for the hammering keys, and wonder what she could be trying to say. Maybe I imagine it, but all night I hear a river of taps washing down over me while Nick snores by my side. And I keep looking but can’t find the reams of typescript she must have.

Meanwhile invisible-Nick is driving our Nick to the brink. He’s scanning with a stopwatch in his free hand, going over the same page again and again.

“Nick, can I ask what you’re doing?”

“Nick wants us to start training to maximize efficiency,” Nick says. “The scanners read one inch per second, Bart, and if we time ourselves we can commit that pace to muscle memory. We’ll move as fast as we can, and no more error messages. Then once we’ve got that, we can address the problem of page flipping, which is inherently wasted motion.”

“You’re joking.”

“Where’s Tracy? Nick would rather inservice all three of us on the new procedures at the same time.”

“Sure, whatever Nick says. I’ll go find her.”

She may as well have vanished into the labyrinths of hell. Floor after floor is silent, empty. I check our camp, nothing. I check the dusted-over corner where the typewriter sits quietly, all of fifteen eerie and dim with most of the lights burned out. Boxes upon boxes stacked full of unshelved books and the unfiled remains of everything else, this will be torture when we get to it. It doesn’t look as if anyone’s been here for 50 years. Age and disuse, mold and crumbled plaster dust, and then a door closing and Nick is behind me. “This is why we’re here,” he says. “People build and they forget, leave everything behind to rot. What we’re doing, in the Cloud, there’s no past so no more forgetting. Everything is continuously updated, all this in front of us in the immediate present, always.”

I open the flap of a cardboard box, lift out a book. The dust jacket’s missing, the black cloth cover frayed, title worn to illegibility on the spine and the binding creaks as it opens. Is it really forgotten, the weight of it left here? Is it lost, I ask myself, as the acid paper dissolves? “Yeah, glad to do my part.”

“Bart, I’m afraid Nick doesn’t want us up this high yet. We have a schedule to stick to.”

“No, I know, I was just looking for her everywhere.”

“We’ll get to this soon enough. Let’s go.”

She doesn’t come back to camp at all that night and I’m worried. Nick mumbles in his sleep, an argument with iNick, like a man overcome by fever and shivering. We’re not losing control, he murmurs, we’re not skipping ahead. She’s here and we’re on task. I pull my sleeping bag up over me and zip as high as it will go, the clicks of hot water pipes and a ringing in my ears.

The next day I’m sure someone’s following me. The air feels heavier, colder, I hear doors open and close. My legs cramp, knees start popping every time I stand. I hear a sneaker squeak on the tile and follow what sound like moans for an hour down unfamiliar rows into corners where the lights have burned out. I find empty study spaces, metal cubicles piled with discarded books and imagine students here, weighted down with fatigue as if chained to these desks. Row after row of silent bodies, lips moving soundlessly, pencils scratching in notebooks and fingers dog-earing pages. I read the titles. At this desk an 18th century economics term paper, at this one a Renaissance history of unknown playwrights. I read notes in margins, imagine outlines on scratch paper, the damned straining to absorb all they can remember, and the ghoulish reference librarian passing between the rows with her strict hair and index cards. Handing down call numbers for more, ever more in a cruel parody of assistance. I imagine them, eyes red and malnourished, one by one collapsing onto the bound journals and ancient encyclopediae strewn before them, dead of boredom and insomnia and if Nick’s right the Cloud can save them.

###

Turning a corner I almost step on Tracy, curled cross-legged between the shelves among unpublished dissertations. She stops scanning, looks at me, she’s started wearing drastic eye makeup. I cough a sort of apology. “Are you lost?” she asks.

“Nick’s been looking for you. He thinks you’re AWOL.”

“I’m not absent; there is no leave. Besides, I’m working.”

“It looks like you’re reading.”

“This is fascinating,” she resumes brushing her scanner down the page.

I sit next to her, “Not the point. We’re already like a century behind, don’t you ever want to get out of here?”

“Do you?”

She loosens the drawstrings of the knapsack at her feet, pulls out a typescript page, lays it flat on top of the page she just scanned and begins brushing from the top.

“What. In. God’s. Name are you doing? That’s going into the same file.”

“It’s like an abacot. Look it up.”

I can only stare at her.

“I’m writing a memoir. Every so often I slip a page in.”

“And you just put the book back? There’s no way to find which ones you’ve ruined.”

“Exactly. No one checks.” She holds the typed page away from her body and lights it on fire, watching it curl and flame and smoke into ash. I launch into a coughing fit as orange and red lick across her face, shimmering spots in my eyes. “I’m adding to the Cloud,” she says.

When she returns to camp Nick’s out cold as he is a bit earlier every day. She drops the knapsack on my shin and leans down over me. “You should start reading before it’s too late. You already missed the beginning,” she kisses my cheek before crawling over her luggage and lying down.

###

Summer’s gone, Tracy’s memoir shrinks and grows from the beginning toward the end, whenever that might be, the last page curling up in flame. I hide with a flashlight in my sleeping bag like ten years old, trying to keep pace with it, the tap tap tap from above racing behind her voice reading the words aloud in my head. With the fall comes Work/Study undergraduates making rounds, wraithlike in black polo shirts, with such maddening regularity and I avoid them. It’s the intrusive eyes that bother me. The lights stay on longer now, and the workday stretches to fill the time but the stacks go on interminable as ever, inch of text after inch, line by line, recto and verso, leaf after leaf, book, then shelf, then aisle, floors, and then the abandoned boxes stored where no one’s seen them for decades in the dust and then books left open and kicked under tables with the marginalia of some doctoral student left in 1924 waiting for us to add to the Cloud forever.

Graduate students are a small but constant presence, as passively nagging as a termite problem. They’re a territorial lot but usually don’t mind if I sit with them, scanning whatever they’re not at that very moment reading, so long as I’m quiet. So godawfully quiet I don’t know how they live like this, sitting in their rows. Some with their own reading lamps plugged into outlets at the desk, fleece blankets over their laps, others getting up every so often to ask the next one to lower the volume of their headphones. It’s unreal the silence they bring onto the floor, they’re living sound dampeners sucking the life out of the air itself. Nick doesn’t have the same rapport with them, and if he’s nearby they move off lumbering in silent packs, grocery bags filled with books, and Nick yelling Wait, we need those!

Nick’s taping charts and pencil-drawn maps and timetables all around the camp, orders and revisions iNick hands down mercilessly. Nick scribbles the hanging papers to oblivion trying to account for where Tracy’s already been. Dark circles spread under his eyes, he’s losing weight and his jaw moves mechanically, grinding teeth in place of food he won’t eat. His delusion’s skewed a bit on him, he talks directly with iNick in the 2nd person now. He says things like This is a good strategy but we need more procedural freedom to accelerate our progress and We’ll meet whatever deadlines you set so long as ultimate responsibility lies with you but the 1st person pronouns don’t seem to have a referent anymore. He’s fanatical about efficiency and holds morning meetings in the washroom, just for me since Tracy’s away wherever. Today he claims to have solved the page-flipping problem. We’re standing against a wall, looking down an unending aisle, and he hands me a book from the shelf.

“You’re going to tear the pages out and lay them end to end. No more flipping. I’ll follow you and scan,” he says.

“I’d literally rather do almost anything else.”

“It’ll be much faster,” he steps toward me, “no more wasted motion.”

“Tearing is a wasted motion, just a different one. Not to mention one that destroys the book.”

“Nick feels the physical object itself is expendable once it’s safely in the Cloud.” He opens the book and starts, slowly and perfectly, tearing out pages. “Fine, I’ll tear. You scan.”

“I’ll be somewhere else. Doing something else.”

“That’s insane,” Tracy says when I tell her later.

“And you’re Miss Rational these days.” She’s grown pale and freckles stand out on her cheeks. We’re sitting among the boxes on fifteen, she’s unpacking and scanning the timecards of some forgotten payroll. “So what is an abacot, anyway?”

“Doesn’t exist.”

“Like something made up?” I hold up a timecard in the dim light: Julianne Peterson Feb. 14, 1957.

“No, the word doesn’t exist. Started as a mistranslation of French, which somebody copied and somebody else changed the spelling a little by mistake. Finally somebody else included it in their dictionary, meaning a crown-type hat worn by kings. Don’t know how they came up with that, then other dictionaries just copied that first one.”

“So you’re adding mistakes to the Cloud?”

She looks at me, glasses slipping on her nose, “I’m adding judgment.”

I arrange the timecards into little stacks and repack the box as she empties it. We sit without talking then until the last card is scanned, the file is uploaded, and the box is again full as though we were never here.

“Want to see something neat?” She stands, wiping at wrinkles in her dress.

I nod. She leads me by the hand running up the stairwell. I hit my head, stumble, and follow floor after floor with my hand in hers. I can’t breathe, pain in my eyebrow and fiberglass needles in my lungs. She stops, bends over with hands on knees. “It’s good for you,” she looks at me but her hair hangs all in the way. “C’mon,” she pulls at my hand again, walking now. I use the railing and make her stop three more times, coughing, as we wind our way into smaller and steeper circles. At the top is a landing, a door and a sign. BookStack Stair 2: No Roof Access. And the door shrieks as she opens it.

It’s a watchtower but with stained glass windows, thick and blue religious figures I’ve never known, the outside light barely coming in. We’re underwater swimming in it, vague shadows of another world darken the glass and I have no idea how high we are, or where. She places her hand against the glass where it looks like the setting sun and I hear the wind pick up just beyond her reach.

“It’s beautiful,” I say mostly to her.

“It is. But it’s not what I wanted to show you,” she points to the room’s large center column, to a door in the column I hadn’t noticed. Inside is a small office, dirty and cobwebbed without even a lamp. She shines the flashlight on the desk, on a rotary phone on the desk. “Nick has no idea this is here. It works.”

I step through the flashlight beam into the room, into a clean swept space on the floor where now I know she’s been sleeping and she follows.

“Is there anyone you need to call?” she asks.

I turn to her, the light rising between us, “No.”

“No one?”

“No.”

She switches off the light, the blue filters deeper in from the outer room, and the saints in the windows stand watch until they, too, go dark.

I wake to whispering, on the ice cold floor, from the best sleep I can remember but cramped all the same. A soft click and rustling and then that shrieking door sends me nearly out of my skin. Her steps fade down the stairwell to nothing, leaving me again to sleep.

###

On three, where I left Nick, there’s nowhere really to step, pages line every aisle, blanket every tile square and still the shelves don’t show a dent. I’m afraid to leave the doorway; it reeks of cigarette smoke here. A sweeping noise moves through the shelves, a whirlwind, then waves of paper in the distance. The undergrads. In the midst of swirling pages, black polos standing out in the white like doomed arctic explorers. They’re pushing brooms, shaking out plastic bags, stuffing them full and the reference librarian’s yelling now so loud, so fast it sounds like German. It’s time, I think, to be somewhere else. But she steps into this same aisle, direct line of sight and here I am backing into the stairwell and letting go of the door. It swings shut with the force of a gunshot and through the little window crisscrossed with wire mesh she’s walking this way, all rage and hate. I run.

The rest of the day I hear her everywhere behind me, and in my poisoned imagination the teenaged furies have grown wings, rushing through the stacks after me with their broom handles poised overhead as flaming swords, their eyes scarlet in the glow and the smoke. I run from every noise, every squeak on the floor and metal click in the pipes above. By lights out I’m utterly lost, under a cubicle desk in a corner, hungry and confused in the freezing air. I lie on my side, arms wrapped around knees, and dream of Tracy when I sleep. She’s bathed in the shades of blue and enfolded in white cloth, her hair turns purple in the light, kneeling and whispering softly over me here on the floor like prayers.

The lights flicker in the morning and burn, I crawl from under the desk and look for the stairs. In the bathroom near camp feet are visible there in one of the stalls, between the bottom of the door and tiny checkered tiles. I turn on the sink and take off my shirt, put my head under the tap and, straightening up again, call out toward the feet, “Nick?”

“Bart?” he answers, hiding from I assume himself and smoking, the cigarette plume’s smothering as it reaches me, I bury my face in a paper towel and hack. I don’t like the look of what remains there when I’m done. That goes right into the trash, I splash my face with water and look into the mirror. “I’m in a nightmare,” sounds like something I’d say, “they’re relentless. Everywhere at once.” But it’s Nick speaking, and then banging on the flimsy walls around him. “They didn’t understand, none of them did. And that woman…” I walk toward him while he describes his discovery and eventual escape, the elevators called for and sent away as decoys, the stairwells and utility closets. His cigarette hisses in the water below him. He tells of the furies and fascist librarian, the long night balancing on the toilet rim and an irrational fear of the sound it would make flushing, that they’d hear him.

“It’s not irrational. They’re really after us, Nick.”

“I know. But Nick tells me he’s negotiating a truce, with a significant payment involved. We just need to lay low.” He draws his feet up and they disappear above the bottom of the stall door.

Camp is well outside the usual undergrad patrols and offers some measure of safety, of what at least feels like safety. Nick’s almost completely encased us in walls of hanging paper at this point. I look around and through Tracy’s luggage fort, hoping to find her memoir, something to lose myself in for a while, but instead find layers of complex lingerie folded and sorted by color and pattern. The purpose of certain buckles, snaps, and webs of strappy elastic are beyond me. I close everything and sit on my sleeping bag, facing away from it all but her disappearances feel sinister now. I think I need to watch her movements more closely at night, and during the day.

Around midterms and finals the stacks fill with actual people around us, but they’re lost and empty in the eyes and we don’t worry. They’re so out of place here they mostly ask us for help even as we wrestle books from them. It’s horrible though, chasing students around this way, their greedy hands trying to take and take from us. Who could know what they’re after? Or when those books would return or how to find them then. I just want them to stay at home, wait comfortably on couches and understuffed beanbag chairs until we’re finished. They’ll never have to come here then, derelict as they are, with the wide eyes and little maps sketched on the damned index cards, the strings of meaningless letters and decimals. Mouths moving dumbly, fingers tracing along the spines for some stitched block of paper, they don’t even know what’s inside, if they need it at all. Wandering, backtracking, they curse the skies for books misshelved or missing altogether. They recall books from each other and fight over limited resources. Just stay home and wait. The Cloud will find what you’re looking for and it will already know what’s inside.

They don’t wait but do stop coming back after exams are done and then it’s very quiet as the snow deepens along the bottom corners of the watchtower windows. Shadowed flurries swim past the angels there and the wind whistles against the blue glass while I sit waiting for Tracy, who vanished in person if not spirit. She still delivers her memoir every day, I find it waiting tucked inside my sleeping bag at night. It started smelling of perfume and, honestly, needing an editor. It’s hurried, as though she’s rushing now toward some end only she can see. I read for clues, some sign of where she is, what she can be thinking, but the story hasn’t caught up with us yet. We’re still stuck in college with her sister and some vague love interest in a water polo player. She buries me in descriptions of falling leaves on the main quad’s rolling lawns, of the blinding sunshine warming nothing and mittens around steaming coffee cups, of hooded sweatshirts and the heavy backpacks on everyone’s shoulders. She writes of the stone buildings and marble columns and crisscrossed paths between them, halls with amphitheater rows of wood tables and too many chalkboards. These long winded lectures she transcribed, it seems, but probably made up with semesters’ worth of notes she can’t possibly remember, all laid out in paragraph after quoted paragraph for reasons only she can know. Telling me of the suit jackets and leather briefcases, the sound of chalk on the cloudy green boards and bourbon bottles pulled from desk drawers in office hours. I read on, racing along the doomed pages, wishing, begging these leaves before they’re consigned to the fire, to get to the point please.

The last several weeks Nick’s been in the bathroom already when I wake, in closed-door meetings with iNick. He hasn’t had time to bother with the nuisance of actually scanning, preferring talk of Taylorized efficiency measurements and motivational strategies, of team-building exercises. He says an increased managerial presence is necessary to keep us all on the same page, and he doesn’t seem to notice the pun, or the irony. By noon he’s visibly shaken, collapsing in nervous exhaustion. And with Tracy MIA I’m left to myself, mostly, making almost no progress. I catch myself sitting frozen, staring intently at nothing, with disconnected sentences stuck in my head like songs, a feeling of remembered dreams. I think of the books now as either empty or solid, like prop books on movie sets for all I could tell you what’s in them. Just endless print and a creeping déjà vu, and I feel like that character in a story I’ve nearly forgotten, too poor to buy the books he wanted so the fool took only the titles and wrote the rest himself.

###

Tracy reappeared after the lights didn’t come on. Either she took pity on us left with only the one flashlight or she’d been somewhere around here all along. Or she was scared, too. Imagine the sun didn’t rise one morning. We felt nothing, no great tremors, no explosion, no trumpets announcing the end of days. At first I thought a Work/Study teen overslept hungover in a strange bed without an alarm clock, woke up lost and sick and fled straight home in shame. But no, the dark lasted long enough we couldn’t explain it away. We were here, sitting on our sleeping bags in the abyss, and no one was coming.

“I, for one, am glad we can just sleep in,” Tracy’s voice from the other side of her luggage.

“You don’t get it,” Nick says. “It was finals last week, this is winter. They don’t have winter classes!”

Tracy shines her flashlight in his face.

“It’s probably a month break,” he continues, “turn that light off. We’re going to be so far behind.”

“Behind what?” is all I can think to ask.

You can only sleep for so long, sadly. Nick hums fugues to himself, setting some kind of mood and Tracy burns through her flashlight battery revising the memoir until the black is all but complete, the mass of these unseen, mute voices collected around us. They haunt me and terrorize Nick, I hear him taking down books and fingering through them as though they were Braille, whispering to himself and inhaling cigarettes, the burning paper and lingering acid trails of glowing red as he gestures toward nothing.

“Bart,” Tracy calls, “I’m bored as shit. Talk to me.”

I feel my way toward and over the walls of her luggage, catching a foot and twisting down to the floor on my back. “There’s no way this is going to last a month,” I say.

“Does it matter?” she reaches for me, hands I think looking for my shoulder, a sense of occupied space.

“I don’t want to sit here like this forever,” I move toward her.

“Then let’s get out of the dark.” She takes me by the arm and stands, leading me shuffling and blind past Nick’s hallucinations up to the watchtower. Every window glows like a lightbox; it must be the middle of the day.

“I’m leaving soon,” she says, sitting down. “I’m done with scanning, I can’t take it anymore.”

“I thought you liked it here. I see you reading all the time. Seems like the perfect job for you.”

“God no, it’s compulsive. If there’s text on a page I have to read it. Can you imagine? Think about all those pages of 8 pt. footnotes, the bibliographies, the indexes.” She leans against the window, breath condensing there under her nose.

“Yikes. I had no idea,” I put a hand on her lower back, “what are you going to do?”

She turns, slides down against the wall to sit. “My sister and I are starting a business. Video editing.”

“Aren’t there already enough people doing that?”

“Not like us. We’re only going to do home movies, tourist’s vacations, that kind of thing.”

“Like kids’ birthday parties and stuff? Nobody watches that crap.”

“Because there’s too much tape to sift through. They already lived it once, who has time to watch the whole thing again? You’d need to live twice as long,” she tucks a lock of bangs behind an ear, brushes an eyelash off a blue cheek. “So that’s why we’re going to go through it and cut out all the boring bits. Voila, the best memories of Florence or nephew’s baptism or whatever. And we’re selling little video cameras that’ll attach to like a hat or coat or something, so people can stop staring into tiny screens their whole trip. You know, if they go to Florence they may as well enjoy it while they’re there.”

“Genius. How are you going to screw this up?”

“Haven’t decided yet, probably something to do with the scraps we cut out.” She wraps her arms around her knees and rests her chin there. “You could come with.”

“I don’t know. I’ll think about it.” And we watch the windows dim and brighten toward blue and fade again four more times before checking again on Nick.

###

The lights were anticlimactically on and we heard him in the washroom, revising revisions of iNick’s schedule. No way for him to know how short lived his plans would be as the librarian’s undergrad minions stepped off the elevator en masse, a lynch mob armed with buckets of soapy water and mops, paper towels and these horrid spray cleaners. We hid like rats, bleach fumes overpowering us on every level, muffling coughs and moving camp every night to stay ahead of them, driven upwards on a rising tide of foaming disinfectant. Days spent in closets, climbing stairs and doubling back, curling under desks until finally we were able to move down past them in the night. We slept then in the chemical smell and worked the next day as they continued upwards, Nick cursing after them.

With Tracy determined to leave, nothing would convince her to just scan a plain old book like a normal person. I followed her around for the company, to spend time with her before insane Nick was the only one left with me here.

“You know you’re not doing what you think you are,” she tells me.

“And what do I think I’m doing?”

“You and Crazy aren’t making some wonderful, liberated world. The opposite, actually. People will look back at this as the moment everything went wrong.”

“But it’s not going wrong. It’s just taking time. When we’re done the Cloud will be there for everyone—whatever they want, whenever they want it, and free.”

“And all stored on Company servers. This,” she holds up her scanner, “is just the first step.”

“A benevolent king benefitting the people.”

“Right,” she pushes her glasses up the bridge of her nose.

She’s scanning floor tiles now, the signs pointing to call numbers, the bookends and dust covered shelves, scanning desktops and sleeping graduate students, brushing her scanner across the spines of books lined row after row, waving it like a wand through the air, scanning empty light.

I asked what she thought would happen to her memoir; she said it’s almost done. Written and mostly in the Cloud and almost destroyed. I think we have two different ideas of what done means. Scattering bits of herself on the wind where they’ll never be found.

I’m about halfway through Holy Alliance: The Unified Force of Church and State Governments in 14th Century Spain and its Effects on the Peasant Population but still thinking about the memoir, my hand freezes. “It’s not that no one will know where to look, but no one will know that they should look.”

“You think maybe that might be part of the point?”

“I mean, someone might stumble across the right search terms and see part of it…” my scanner is giving me all kinds of error messages.

“Somebody will find a page of it while they’re reading.”

“Nobody is going to scroll through a whole book anymore.”

“See? That’s what I’ve been telling you. So my book is like a reward, a little mystery for those who do. If you don’t read the whole book you might miss out on a clue.”

“You’ve got a lot of eggs in that basket there.”

She looks around at the shelves, waves her arm from left to right. “And if they don’t, so what? Same fate as some of the best minds in history.”

My scanner beeps erratically; I turn it off and shut the book. Tracy lays out flat on her back and stretches, “It’s comfortable here.”

###

In the dream I was submerged in fire, but a movie’s fire, like photographs of the sun, blinding orange explosions and the smoke venting mysteriously somewhere. Instead of being consumed in flame and ash the books glowed white hot and melted into thick lava pools on the floor, rising around me. Nick dissolved into a black heart of coal, iNick the fuel, and Tracy’s eyes reflected the flame, her skin shone brightly through the smoke as I rolled and crawled on my belly toward her. Face to the floor, sputtering and burning in the weirdly melted pages. The noise was like a river, a whoosh, a sliding fluid and a crackle. She was a shining skeleton, her teeth exposed smiling, she turned away toward the elevator. iNick stood, stiff and crumbling, charred and barely hanging together, turning his head after her. Raising an arm, fire dancing along the length of it, pointing after her. I was being washed back on a current, swimming for the elevator against it, drowning. Worry in Tracy’s eyes for the first time. The doors opened and she stepped inside. The watchtower’s angels tore the clothes from their bodies and wept, the bookshelves around me disintegrating. Tracy’s face burned to that skull’s helpless grin, waving goodbye as the doors closed, the elevator car rose through the tunnel behind the burning walls. And iNick, unmovable, laughing now as he swung the charcoal arm around to point at me.

I woke, I hope understandably terrified, to a flashlight bulb staring down on my face. Nick snoring off in a corner in the dark and Tracy says, “It’s time to go.” She leads me to the ninth floor and sits me down at a desk, she sits across from me and turns off the light. We sit watching the shapes of one another dissolve into spots of color swimming in the black. It’s maybe 20 minutes before the lights click and flicker on and she’s still exactly there at the table across from me, confirming the statue-image of her I had in my mind this whole time. She stands as my eyes adjust, takes Monotheism and Empire from a nearby shelf and returns, opening it on the table in front of me.

“I’m leaving,” she says.

“I know.”

“No. I mean now. I just want you to do one last thing for me before I go.” She pulls my scanner out of her knapsack and sets it next to my hand.

“Why do you have that?”

“For this.” She places both hands down on the open book, palms up and perfect fingers outstretched. “Scan,” she says.

“Why me?”

“I can’t do it myself, silly. I need your help.”

Her hands, my scanner, her memoir floating in the ether. “I mean, your fingerprints. They’ll be in my scanner. They’ll come to me for everything that you’ve done.”

“They never check.”

“But if they do.”

“Then I want you to know this isn’t everything. It feels like it right now, because you’re inside it, but all you have to do is step outside.”

I take hold of her by each wrist, one at a time, and scan.

“See, that wasn’t so bad. The first step is always the hardest.” She leaves for the elevator then, looks back over her shoulder until the doors open. Inside, she hits a button it looks like somewhere in the middle but it’s hard to tell and she blows a kiss in my direction. She’s gone, I’m coughing again and hard, and since I’m here already I might as well get to work. The scanner blinks, ready for the next file, and I flip back through the pages on the table in front of me to start from the beginning.

BIO

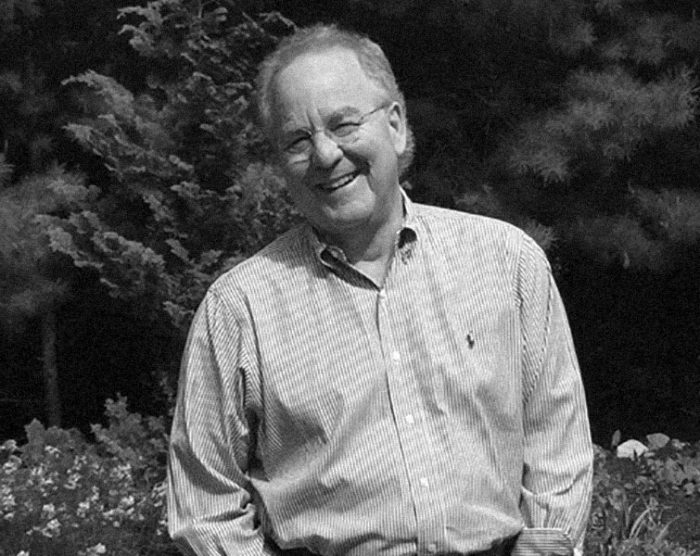

T.E. Winningham holds a PhD in Literature from the University of Southern California and a BA from the University of Iowa. His work has appeared in Fourth Genre, Anamesa, and the Overtime Chapbook series, among other journals. He currently lives in Los Angeles.

T.E. Winningham holds a PhD in Literature from the University of Southern California and a BA from the University of Iowa. His work has appeared in Fourth Genre, Anamesa, and the Overtime Chapbook series, among other journals. He currently lives in Los Angeles.

Born and raised in Sioux Lookout, Ontario, John Tavares is the son of Portuguese immigrants from Sao Miguel, Azores. His formal education includes a two-year GAS diploma from Humber College with concentration in psychology, a three-year journalism diploma from Centennial College, a Specialized Honors BA in English from York University. He’s worked as a research assistant for the Sioux Lookout Public Library and the Northwestern Ontario regional recycle association with the public works department. He also worked with the disabled for the Sioux Lookout Association for Community Living. Meanwhile, his short fiction has been published in a wide variety of “little magazines” and literary magazines, online and in print, in the United States and Canada. Following journalism studies, he had articles, photography, and features published in East York Observer, East York Times, Beaches Town Crier, East Toronto Advocate, Our Toronto – as well as community and trade newspapers such as York University’s Excalibur and Hospital News, where he interned as an editorial assistant. John recently wrote a novel.

Born and raised in Sioux Lookout, Ontario, John Tavares is the son of Portuguese immigrants from Sao Miguel, Azores. His formal education includes a two-year GAS diploma from Humber College with concentration in psychology, a three-year journalism diploma from Centennial College, a Specialized Honors BA in English from York University. He’s worked as a research assistant for the Sioux Lookout Public Library and the Northwestern Ontario regional recycle association with the public works department. He also worked with the disabled for the Sioux Lookout Association for Community Living. Meanwhile, his short fiction has been published in a wide variety of “little magazines” and literary magazines, online and in print, in the United States and Canada. Following journalism studies, he had articles, photography, and features published in East York Observer, East York Times, Beaches Town Crier, East Toronto Advocate, Our Toronto – as well as community and trade newspapers such as York University’s Excalibur and Hospital News, where he interned as an editorial assistant. John recently wrote a novel.

T.E. Winningham holds a PhD in Literature from the University of Southern California and a BA from the University of Iowa. His work has appeared in Fourth Genre, Anamesa, and the Overtime Chapbook series, among other journals. He currently lives in Los Angeles.

T.E. Winningham holds a PhD in Literature from the University of Southern California and a BA from the University of Iowa. His work has appeared in Fourth Genre, Anamesa, and the Overtime Chapbook series, among other journals. He currently lives in Los Angeles.

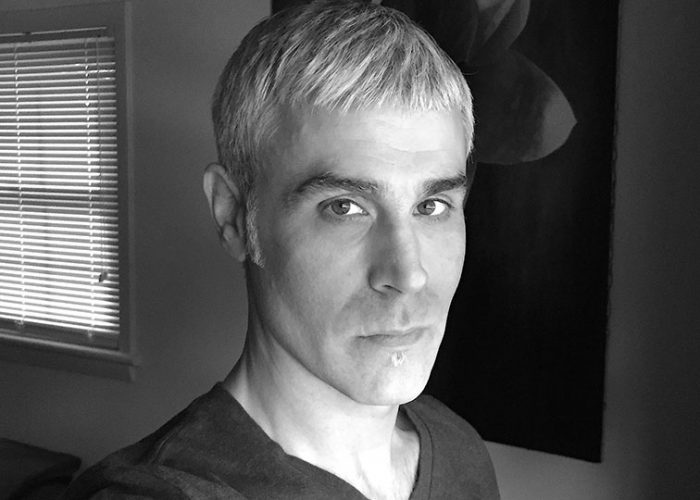

Brad Rose was born and raised in Los Angeles, and lives in Boston. He is the author of Pink X-Ray, Big Table Publishing, 2015 (www.pinkx-ray.com). Twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize in fiction, Brad’s poetry and fiction have appeared in The Los Angeles Times, Folio, decomP, The Baltimore Review, The Midwest Quarterly, Lunch Ticket, San Pedro River Review, Off the Coast, Heavy Feather Review, Posit, Third Wednesday, Boston Literary Magazine, Right Hand Pointing, The Molotov Cocktail, and other publications. Brad is the author of three electronic chapbooks, all from Right Hand Pointing: Democracy of Secrets,

Brad Rose was born and raised in Los Angeles, and lives in Boston. He is the author of Pink X-Ray, Big Table Publishing, 2015 (www.pinkx-ray.com). Twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize in fiction, Brad’s poetry and fiction have appeared in The Los Angeles Times, Folio, decomP, The Baltimore Review, The Midwest Quarterly, Lunch Ticket, San Pedro River Review, Off the Coast, Heavy Feather Review, Posit, Third Wednesday, Boston Literary Magazine, Right Hand Pointing, The Molotov Cocktail, and other publications. Brad is the author of three electronic chapbooks, all from Right Hand Pointing: Democracy of Secrets,

Mitchell Krockmalnik Grabois has had over a thousand of his poems and fictions appear in literary magazines in the U.S. and abroad. He has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, The Best of the Net, and Queen’s Ferry Press’s Best Small Fictions for work published in 2011 through 2015. His novel, Two-Headed Dog, based on his work as a clinical psychologist in a state hospital, is available for

Mitchell Krockmalnik Grabois has had over a thousand of his poems and fictions appear in literary magazines in the U.S. and abroad. He has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, The Best of the Net, and Queen’s Ferry Press’s Best Small Fictions for work published in 2011 through 2015. His novel, Two-Headed Dog, based on his work as a clinical psychologist in a state hospital, is available for

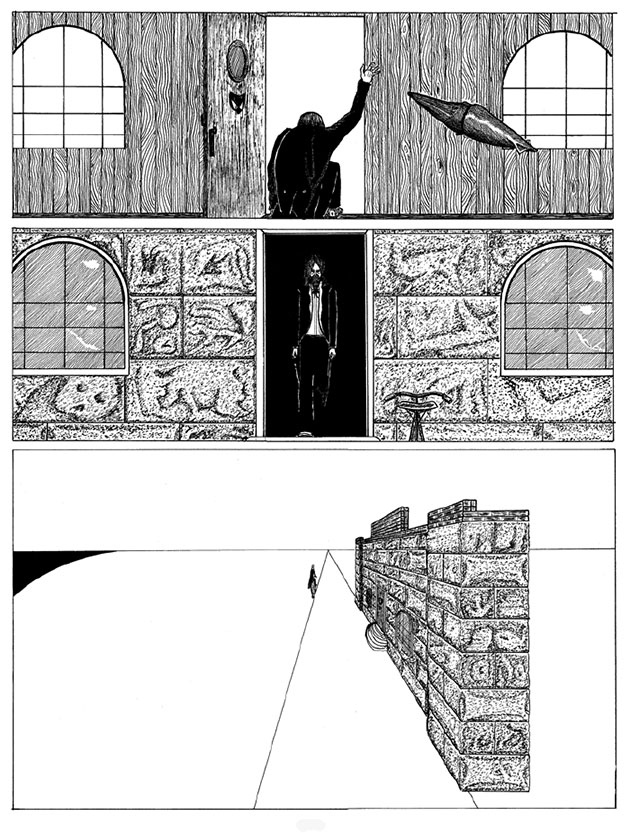

Brad Gottschalk is an exile from the realm of live theater. Currently he is a cartoonist living in Madison, Wisconsin. His art and comics have appeared in Raven Chronicles, Nerve Cowboy, and Berkeley Fiction Review. Read more of his work at

Brad Gottschalk is an exile from the realm of live theater. Currently he is a cartoonist living in Madison, Wisconsin. His art and comics have appeared in Raven Chronicles, Nerve Cowboy, and Berkeley Fiction Review. Read more of his work at

Oliver Timken Perrin is a native of the American South. His poems have appeared in Bohemian Ink, Scapegoat Review, and the Negative Capability Press anthology Stone River Sky. Perrin also co-wrote the independent feature film Crude which received the 2003 IFP Los Angeles Film Festival Target Filmmaker Award for Best Narrative Feature and a Special Jury Prize at the Seattle International Film Festival.

Oliver Timken Perrin is a native of the American South. His poems have appeared in Bohemian Ink, Scapegoat Review, and the Negative Capability Press anthology Stone River Sky. Perrin also co-wrote the independent feature film Crude which received the 2003 IFP Los Angeles Film Festival Target Filmmaker Award for Best Narrative Feature and a Special Jury Prize at the Seattle International Film Festival.

Jill Jepson is the author of

Jill Jepson is the author of

Stephanie Dickinson, an Iowa native, lives in New York City. Her work appears in Hotel Amerika, Mudfish, Weber Studies, Fjords, Water-Stone Review, Gargoyle, Rhino, Stone Canoe, Westerly, and New Stories from the South, among others. Her novel Half Girl and novella Lust Series are published by Spuyten Duyvil, as is her recent novel Love Highway, based on the 2006 Jennifer Moore murder. Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg, was released in 2013 by New Michigan Press. Her work has received multiple distinguished story citations in the Pushcart Anthology, Best American Short Stories, and Best American Mysteries.

Stephanie Dickinson, an Iowa native, lives in New York City. Her work appears in Hotel Amerika, Mudfish, Weber Studies, Fjords, Water-Stone Review, Gargoyle, Rhino, Stone Canoe, Westerly, and New Stories from the South, among others. Her novel Half Girl and novella Lust Series are published by Spuyten Duyvil, as is her recent novel Love Highway, based on the 2006 Jennifer Moore murder. Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg, was released in 2013 by New Michigan Press. Her work has received multiple distinguished story citations in the Pushcart Anthology, Best American Short Stories, and Best American Mysteries.

Janice E. Rodríguez inhabits two realities—the rolling hills and broad valleys of her native eastern Pennsylvania, and the high, arid plains of her adopted land of Castilla-León in Spain. She currently teaches Spanish at Albright College in Reading, Pennsylvania. When she’s not teaching, writing, or gardening, she’s in the kitchen working her way through a stack of cookbooks. She can be found online at

Janice E. Rodríguez inhabits two realities—the rolling hills and broad valleys of her native eastern Pennsylvania, and the high, arid plains of her adopted land of Castilla-León in Spain. She currently teaches Spanish at Albright College in Reading, Pennsylvania. When she’s not teaching, writing, or gardening, she’s in the kitchen working her way through a stack of cookbooks. She can be found online at

Abigail George is the author of ‘Africa Where Art Thou’ (2011), ‘Feeding the Beasts’ (2012), ‘All About My Mother’ (2012), ‘Winter in Johannesburg’ (2013), ‘Brother Wolf and Sister Wren’ (2015), and the forthcoming ‘Sleeping Under Kitchen Tables in the Northern Areas’ (2016). Her poetry has been widely published from Nigeria to Finland, and New Delhi, India to Istanbul, Turkey. Her fiction was nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She briefly studied film and television production at the Newtown Film and Television School opposite the Market Theater in Johannesburg. She is the recipient of writing grants from the National Arts Council (Johannesburg), the Centre for the Book (Cape Town), and ECPACC (Eastern Cape Provincial Arts and Culture Council) (East London). She writes for Modern Diplomacy, blogs with Goodreads, and contributed to a symposium for a year on Ovi Magazine: Finland’s English Online Magazine.

Abigail George is the author of ‘Africa Where Art Thou’ (2011), ‘Feeding the Beasts’ (2012), ‘All About My Mother’ (2012), ‘Winter in Johannesburg’ (2013), ‘Brother Wolf and Sister Wren’ (2015), and the forthcoming ‘Sleeping Under Kitchen Tables in the Northern Areas’ (2016). Her poetry has been widely published from Nigeria to Finland, and New Delhi, India to Istanbul, Turkey. Her fiction was nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She briefly studied film and television production at the Newtown Film and Television School opposite the Market Theater in Johannesburg. She is the recipient of writing grants from the National Arts Council (Johannesburg), the Centre for the Book (Cape Town), and ECPACC (Eastern Cape Provincial Arts and Culture Council) (East London). She writes for Modern Diplomacy, blogs with Goodreads, and contributed to a symposium for a year on Ovi Magazine: Finland’s English Online Magazine.

Raised in a French fishing village, P.M. Neist acquired her storytelling skills from a colorful cast of spirited relatives. After moving to the United States, Neist switched to writing in English. Soon after, she started drawing. She is the author and illustrator of Barely Behaving Daughters, an illustrated alphabet of girls who like to do as they please.

Raised in a French fishing village, P.M. Neist acquired her storytelling skills from a colorful cast of spirited relatives. After moving to the United States, Neist switched to writing in English. Soon after, she started drawing. She is the author and illustrator of Barely Behaving Daughters, an illustrated alphabet of girls who like to do as they please.

Taylor García’s short fiction has appeared in Chagrin River Review, Driftwood Press, Fifth Wednesday Journal, Hawaii Pacific Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and Caveat Lector. He also writes the weekly column Father Time at the

Taylor García’s short fiction has appeared in Chagrin River Review, Driftwood Press, Fifth Wednesday Journal, Hawaii Pacific Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and Caveat Lector. He also writes the weekly column Father Time at the

Harumi Hironaka is a Japanese/Peruvian self-taught painter and illustrator, living in São Paulo, Brasil.

Harumi Hironaka is a Japanese/Peruvian self-taught painter and illustrator, living in São Paulo, Brasil.

adam l. is currently a freshman at Yale-NUS College, Singapore. he is drawn to the limitation of words, and how even in this limitedness, meaning and emotion can be conveyed effectively. he believes that all poetry is confessional, for all poetry came from within us; and the best ones are vulnerable and raw. at times when words seem utterly insufficient, he turns to physical movement in dance and theatre. if interested in interacting or collaborating, he can be reached at theartistadam@gmail.com.

adam l. is currently a freshman at Yale-NUS College, Singapore. he is drawn to the limitation of words, and how even in this limitedness, meaning and emotion can be conveyed effectively. he believes that all poetry is confessional, for all poetry came from within us; and the best ones are vulnerable and raw. at times when words seem utterly insufficient, he turns to physical movement in dance and theatre. if interested in interacting or collaborating, he can be reached at theartistadam@gmail.com.

Matt McGowan has a bachelor’s degree in history and a master’s degree in journalism, both from the University of Missouri. He was a newspaper reporter, and for many years now he has worked as a science and research writer at the University of Arkansas. His stories have appeared in Valley Voices: A Literary Review, Deep South Magazine, Pennsylvania Literary Journal, Open Road Review and others. He lives with his wife and children in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Matt McGowan has a bachelor’s degree in history and a master’s degree in journalism, both from the University of Missouri. He was a newspaper reporter, and for many years now he has worked as a science and research writer at the University of Arkansas. His stories have appeared in Valley Voices: A Literary Review, Deep South Magazine, Pennsylvania Literary Journal, Open Road Review and others. He lives with his wife and children in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Michael Penny was born in Australia, but moved to Canada as a teenager. He now lives on Bowen Island and works as a consultant on regulating professions. He has published five books of poetry, most recently, Outside, Inside from McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Michael Penny was born in Australia, but moved to Canada as a teenager. He now lives on Bowen Island and works as a consultant on regulating professions. He has published five books of poetry, most recently, Outside, Inside from McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Larry Fronk grew up in the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains in Upstate New York, and now resides on the east side of Cincinnati, Ohio. Larry recently retired after a 36 year career of public service working in local government in the areas of urban planning, community development and local government management. Upon entering Act II of his life Larry decided to pursue his passion for writing and enrolled in a creative writing class at the University of Cincinnati, Clermont College. This is Larry’s first published work.

Larry Fronk grew up in the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains in Upstate New York, and now resides on the east side of Cincinnati, Ohio. Larry recently retired after a 36 year career of public service working in local government in the areas of urban planning, community development and local government management. Upon entering Act II of his life Larry decided to pursue his passion for writing and enrolled in a creative writing class at the University of Cincinnati, Clermont College. This is Larry’s first published work.

Belinda Subraman has been writing poetry since the 6th grade and publishing since college. She had a ten year run editing and publishing Gypsy Literary Magazine. Six of those ten years were from Germany where she was a Bohemian outcast among officer wives. She edited books by Vergin’ Press, among them: Henry Miller and My Big Sur Days by Judson Crews. While in Germany she also published the Sanctuary Tape Series which was a mastered compilation of audio poetry and original music from around the world. If you interview her about her publishing days you will discover that she threw out a whole Charles Bukowski manuscript because he told her to just trash what she didn’t like. THEN she found out he was Famous. She might have kept the manuscript but still would not have published it. (It wasn’t his best work). Bukowski, Burroughs and a few other literary figures did make it into some of the first Gypsy issues, however.

Belinda Subraman has been writing poetry since the 6th grade and publishing since college. She had a ten year run editing and publishing Gypsy Literary Magazine. Six of those ten years were from Germany where she was a Bohemian outcast among officer wives. She edited books by Vergin’ Press, among them: Henry Miller and My Big Sur Days by Judson Crews. While in Germany she also published the Sanctuary Tape Series which was a mastered compilation of audio poetry and original music from around the world. If you interview her about her publishing days you will discover that she threw out a whole Charles Bukowski manuscript because he told her to just trash what she didn’t like. THEN she found out he was Famous. She might have kept the manuscript but still would not have published it. (It wasn’t his best work). Bukowski, Burroughs and a few other literary figures did make it into some of the first Gypsy issues, however.