The Claiborne Refuge Workbook

by Clarissa Nemeth

What to Expect at Claiborne Refuge

God brought you to the refuge to save your life from alcohol and/or drugs, through a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. You are not here by chance, but by God’s plan. Jesus says, “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11:28).

Throughout your program at the Refuge, you will be pointed to Jesus Christ as the Bible describes and presents him. He alone can give you victory over substance abuse. “If therefore the Son shall make you free, you shall be free indeed” (John 8:36).

You will learn to pray, to share your burdens with Christ, and to experience the peace and comfort of his care for you. “Cast all your anxieties on Him, for He cares about you” (1 Peter 5:7).

You will learn of your need to trust and depend on Jesus Christ, not only for victory over abusive substances, but for literally everything in your life. “Abide in me, and I in you. As the branch cannot bear fruit of itself unless it abides in the vine, so neither can you, unless you abide in Me” (John 15:4).

THE PRINCIPLES OF LIVING

You admit your are powerless over your addiction, that your life has become unmanageable.

Q. Why is it so liberating to know that you are powerless over your addiction?

Your cousin went to prison a few years back for stealing the Hamblen County Sheriff’s car. He got liquored up and took it right out of the sheriff’s driveway on a joyride, then ran it into a ravine down by Ratliff Road. After his picture got in the paper your grandma said there was something wrong with the men in your family, some bad line in the blood that just kept passing down. You already knew that. Everybody in the county knew that.

Your grandfather once shot a man in the face just because he thought he was ugly. One uncle beat his wife so hard he gave her epilepsy. Last time you saw your daddy, he had warrants out in three different states. Your older brother got so high once he ran half-naked through a plate-glass window, trailing blood down the road and screaming about the end times. A cousin out in Jefferson County raped a little girl in Dandridge. He said he didn’t even know why he did it, just seemed like a good idea at the time.

You wanted to be different. You wanted to be better. Look how far that got you. You were – you are – just like the rest of them. You tried all you could, and it wasn’t enough.

Here they tell you over and over again that nothing you can do will fix your life. They tell you it’s time to surrender to God, that he wants you to come to him, that they are all praying you will let him embrace you. Why not let God try and fix you, if he wants to so much? After all – and they will remind you of this – you don’t have much left to lose, do you?

Paul explains the struggle between good and evil in Romans 7:13-24. Put that same struggle in terms of your addiction.

Paul says that he wants to do good, that he wishes for it, but that the evil within him longs for nothing but sin.

You know about that longing. Remember the first time you got drunk, the first time you got high, the first time you stole, the first time you snorted a line of Oxy. The sixth time. The fortieth time. The seventy-seventh time. No one made you do all of that. There was always a choice. How many times were you convinced that it would be better just to die? But that burning, clattering wanting coursed through you, and always you took the next swallow, the next pill, the next snort, the next drink. There was a little hollow voice inside of you mouthing no and it always got drowned out by that howling need for more, more now, again. It got to where that wanting grew into a creature all its own just carrying you along with it. Even now you feel the wanting. In your skin, your teeth, your very bones. The wanting wants everything; it will want until there is nothing left of you.

But if they split you open right now and that wanting poured out, there would still be a tiny sliver of you left in there, scrabbling for a little more purchase on this life you almost threw away.

Paul says it isn’t easy. You could tell him, no shit.

You make a conscious decision to turn your life over to the care of God; you open your heart and mind to the power which is Jesus Christ, your Lord and Savior.

Q. How do you have access to God’s power?

Remember what happened when you killed your first deer? Your uncle made you run your knife down the animal’s gut and look at what spilled out. He made take off your glove and reach down into that steaming pool of blood with your bare fingers. He made you wipe that hot blood in two broad streaks below your eyes. You’re a man now. You’ve been blooded. Trouble runs in your blood. Blood alcohol. Bloodshot eyes. Bloody footprints tracking on your wife’s carpet. Blood smeared on tissues, dripping out your nose in red droplets to stain the pillowcase, on your toothbrush from bleeding gums. Blood pounding in your ears. Blood on her face when you split her lip; blood on yours when she spat it back at you. Blood in your blue veins, beading when you pull out the needle. Got to get it in your bloodstream so it feels good.

Blood on the cross. Christ bled, too. Just like you.

Q. How do you know that God will not just get tired of you and throw you out of His kingdom?

You don’t have too many good memories of times when you weren’t high or drunk, but one of them is the day your daughter was born. You got drunk to the gills that night, sure, but the moment she came into the world, you were there. You and your wife maybe never should have had a kid in the first place, but the two of you made that little person, and the first time you held her, you remembered thinking it was impossible that you’d had any part to play in creating something so tiny and perfect.

Of course, later you learned that tiny perfect creature could scream about as loud as her mother, could cry until you wanted to tear down the walls. She could shit more than a horse and puke all over the place and throw her food everywhere. When she got to be a toddler she started throwing tantrums, and once she gave you a black eye – you had to lie to the guys at the bar and tell them you got into a brawl out in Jeff City. Sometimes you’d imagine shaking her until she shut up; sometimes you wished she didn’t exist. But you never forgot that you made her. You’d never say you did a real good job as her father so far, but still – you never forgot that you made her.

Supposedly, God feels the same way about you. You have trouble imagining that. But you can’t ever imagine being as small and as new as your daughter on the day she was born, either. Another impossible thought – but true. Why not the other?

You admit to God and to yourself the exact nature of your wrongs and ask Him to enable you to turn from them.

Q. Why is God so insistent that you confess your particular sin particularly?

The first time you got arrested, they caught you stealing money from unlocked cars in the high school parking lot. The cop who found you brought you home to your grandma and she slapped you so hard your ears started ringing. You said your friends put you up to it.

She slapped you again and said, you lie like a pig in the mud.

No, you insisted. They made me do it. I didn’t even want to. I’m sorry.

You’re the sorriest goddamn fool I ever saw, she agreed, but you ain’t sorry for stealing. You tell me now what you’re sorry for. Go on. Tell me the truth.

Back and forth you went like that, slapping and cussing until you finally said, Fine! It was me. It was all me. And I’m just sorry I got caught.

There you are, she said. Don’t you lie to yourself about what you done or why you done it. You own what you’re sorry for. Only way to go about it.

She came to court with you later, made you shave and put on nice pants, stood beside you in front of the judge, and made you tell him all that. What you did and why you did it. The judge said at least you were honest.

That time, you got community service. That time.

Q. It is not enough to confess your sins…what else must you willfully do?

Your daddy knew what a rat he was, knew it better than anyone. He’d tell you all the time, when you were real little, how sorry he was. Sorry for hitting you, sorry for spending the grocery money, for smashing the window, for letting the electricity go out again. Your daddy was just about the sorriest man you ever knew.

See how far those sorries got you. Sorry didn’t make the bruises go away. Sorry didn’t fill your belly. Sorry didn’t clean up the glass in the carpet. Sorry didn’t pay the electric bill. You can’t heat up sorry on a hot plate. Can’t give sorry to the repo man. Can’t crawl under sorry to sleep at night.

The Lord didn’t say to the cheating woman, I’m real glad you’re so sorry, honey.

He said, Go, and sin no more.

You make direct amends to people you might have harmed except when to do so might injure them or others.

Q. So often in your life, you have betrayed the trust of loved ones. Is it possible to make amends?

If you made a list of everyone you ever hurt, you could fill pages and pages. If you could crawl on your hands and knees to everyone you’d ever hurt, you’d scrape your shins and palms to the bone and still have people left to crawl to.

It should be getting easier now, as the days pass, as the fog lifts from your brain, to remember in excruciating detail every wrong. You remember your daughter’s face, for instance, on the day you came home high and ran over her dog in the driveway. A small note on your ledger of debts, but not one that you will ever forget. You will know every way you failed, every way you hurt, every way you disappointed. Tally them; tattoo them on your skin; carry them in your mouth like bitter candies.

You remember your wife, soft and tart the way she was in high school, her face unlined, her laugh like a tinkling bell. She could drink you under the table back when you first met her; that, of course, was some years before you started living on the table. You remember the way her nose felt when you slammed your fist into it, how easily it gave to your strength, the pop of the breaking bone. It didn’t even leave a bruise on your knuckle, but what it did to her —

Sometimes it will feel as if everything and everyone you ever touched fell apart. No one who knows you trusts you. No one who knows you believes you love them more than a ziplock baggie of Oxy or a bottle of Early Times. It’s easy to believe that God can forgive you; that’s his job, it’s what he promised to do. He wrote a whole book on the subject. But your grandma, your wife, your daughter – they never made any such promise.

You cannot make them forgive you. You cannot make them trust you. You can’t make them love you. All you can do is put on your dress pants, your nice shirt, your shined shoes, and wait for them each Sunday afternoon. Hope they will come. Hope they will see you there, just once, waiting. Trying. Putting them first, for once.

The rest – it’s up to them.

Q. The carrying of grudges and bitterness takes you away from the blessings of God. Can you be free from such mind control?

If you made a list of everyone who ever hurt you, you’d fill pages and pages. You know about grudges. You know about settling scores.

You can’t quite remember how old you were when your grandma told you your mama’s relations in Harrogate didn’t want anything to do with you after she died. It was after your daddy left, which they held up as proof that you came from trash. You told your grandma you didn’t care, that you didn’t want anything to do with them, either. But the first time you did crank in high school, you drove out to the cemetery in Harrogate with the idea of taking a baseball bat to your mama’s headstone. You swung that thing till your arms ached, bashing it against the granite again and again. When you were done the bat was all dinged up but that headstone didn’t look too different. You settled for smashing the little vases of flowers her relations put up beside it. A few weeks later you drove by again and saw those vases had been replaced. It was like you hadn’t even been there. All that anger, searing you, burning up inside, came to nothing.

If you expect God to forgive you, if you hope that others will forgive you, you have to forgive in turn. Sometimes your anger feels like the mountains you see from your window: massive, solid, insurmountable. But mountains can be climbed. Step by step. They say the view up top is something to see indeed.

You seek through the power of prayer and meditation a conscious contact with God, praying only for knowledge of His will for you and the power to carry that out.

Q. Does God actually hear prayer?

When you were in the Claiborne County Correctional Facility, just a skip down the street from where you are now, you were coming off the Oxy and were sure you were going to die. They put you in a cell with a guy they called Brother Keith. Brother Keith talked to God all the time. You were curled up in a ball, shivering and trying not to shit yourself, gnawing on that nasty prison blanket just to keep from moaning, and there’s Brother Keith, praying. Peering out the tiny slit of a window that looked out onto the parking lot and saying, Another beautiful day, Lord, thank you very much. Eating breakfast and saying, Lord, you know how much I love when they have them hot biscuits, thank you very much. Tidying up his bunk and saying, Lord, if it’s your will I sure could use some healing on these old knees of mine.

Finally you screamed at Brother Keith to just shut up, shut the hell up for five fucking minutes. God didn’t give two shits about his knees, God wasn’t in this place, God wasn’t anywhere, and if he was he would surely have killed you by now like you’d been asking him to.

Brother Keith let you holler at him for a while, then came over and knelt down next to you, even though you must have smelled like roadkill. Brother Keith put his cool hands on your sweaty forehead and said, Lord, I pray here for my brother who is in pain. I pray that you will comfort him. I pray that you will give him just a few moments of peace.

Maybe it was the prayer; maybe the touch of his hands; maybe it was hearing, for the first time, someone pray for you instead of at you. Angels didn’t come down from the ceiling. Your pain didn’t even go away, but while Brother Keith was praying for you, you didn’t feel like dying anymore.

You didn’t quite believe that God would ever listen to you. You were not even sure, then, that you believed in God. But you did start to believe in Brother Keith, that a trickle of his faith might flow through his hands and into you.

Eventually you found out that Brother Keith was in the Claiborne County Correctional Facility because he’d been driving down Lipcott Road in Tazewell on an expired driver’s license and hit a little boy on a bike, a little boy who would never walk again.

Brother Keith called himself an instrument of God.

Sure, you quipped. Jesus healed all the cripples, so you had to go make him a new one.

But Brother Keith showed you a letter he’d gotten from that boy’s mother. Pretty simple letter. She said that she was praying for him just as she prayed for her own son; that she forgave him.

That surprised you. If someone broke your daughter’s back, you’d never write a letter like that, not in a million years.

But Brother Keith said that was living in God’s image. That God loved you no matter what you did, that he would forgive you no matter what, and that he felt your pain as keenly as he felt that boy’s, and that mother’s, and his own.

Brother Keith is the reason you’re here. Before you left for the refuge, you made him promise to pray for you. You still aren’t sure that God hears you when you pray, but it makes you feel better to know that Brother Keith is out there praying for you.

You’re pretty sure God listens to him.

Q. What is the “power” that God gives you?

Your whole life you’ve been told you weren’t good enough. Not smart enough, not tall enough, not handsome enough, not rich enough. You’ve been a disappointing son, grandson, brother, boyfriend, father, and friend. There have always been people who’ve had more than you, did better than you, felt happier than you. It always felt impossible to catch up; it always felt like all the nice things in life were for other people.

But if you believe in God, you have to believe that God himself made you, and that he didn’t make you wrong. That’s the hardest thing for you to accept: He didn’t make you wrong. You are God-made and God-breathed as much as Adam, as much as the Pope, as much as the Queen of England. And as much as your father, your mother, and your pedophile cousin out in Dandridge.

You are no worse than anyone, no better than anyone. There are no magic words, no combination to unlock the possibility of good within you, no pill to take that can change you forever. All the power God can give to you, he already has. All you have to do for God to love you is be.

You are good enough. That knowledge frees you and it scares you. It redeems you and it humbles you. It makes you grieve and it gives you hope. You are good enough. You are good enough. You are good enough.

You have come to accept the priority of your life as: God, family, church, work, and self.

Q.What’s the big deal about “family”?

Think about your family. Your mama and your grandfather are resting deep in the Claiborne County earth. You wonder if the warrants caught up with your daddy before the drugs did. You may never know. Your brother is in Memphis, doing his third year of six for meth manufacturing. Your grandma, so old now she’s half-deaf and her hair is falling out, still kills her own chickens and bakes her own bread. You have a wide constellation of cousins and aunts and uncles in Jefferson, Hamblen, and Claiborne counties. Throw a rock around here and like as not you’ll hit someone you’re kin to. Sometimes you feel like all these people who know you are a web to catch you if you fall. Sometimes they feel like your destiny, binding you to a fate you never wanted. How much easier would it be to just start again, in a new place, where no one knows you? To make a new family full of people you haven’t already disappointed?

Remember the bonfires with your cousins; remember running through the woods with your brother; remember your grandma feeding you chicken broth when you were sick. Remember your uncle teaching you to shoot. Remember your daddy, tossing you up into the air when you were little. He never let you hit the ground. You were never as alone as you thought you were.

Think about your daughter. She’s seven now, with long blonde hair she won’t let her mama cut. Think about the last time you saw her happy, blowing dandelions in the front yard. Think of her laugh like the prettiest music you ever heard. Your wife will not come to see you on Sundays, but she sends you your daughter’s drawings in the mail. You hang them up on the drab particleboard walls. It looks like her favorite color is green.

Your wife will not come to see you, not yet, but she sends you those drawings and some shirts of yours that she’s mended. The packs of cigarettes that get you through the day. The butterfinger candies she knows are your favorite. Maybe she shouldn’t be, but she’s still your wife. She’s still the mother of your child.

They are yours. You are theirs. Your family made you and unmade you, as you made and unmade them. They gave you all the pain and love you’ve ever known. They are the tether to a past you’d like to forget, but also the bridge to a future you might make. You can’t take one without the other.

Q. Why should God be the number one in your life?

From your window at the refuge you can see the mountains on the Tennessee/Kentucky border. As long as you can remember, they’ve been there. You can remember taking field trips up there when you were still in school. You remember learning about how fragile they really are, how each one is made up of so many different parts; each flower and root and stem and log have a role to play. The tallest pine tree and the biggest bear are just as important as the smallest salamander and the tiniest ant.

It is hard for you to believe in God from inside a little room with an altar and some stained glass windows. Harder still to believe in God from the plywood benches of the refuge, surrounded by men who stink of sweat and tobacco and unwashed bodies. God doesn’t seem beside you in the lukewarm showers, the smell of someone else’s shit fogging the air in the tiny bathroom; he doesn’t walk with you to the sterile dining room where you recite your daily Bible verse to the Pastor’s assistant each morning at breakfast.

But looking out at those mountains, it’s easier to believe in God and his power. Each morning when you look out there, you try to meditate on God’s creation. Just one of those mountains is more complex than anything you’ve ever known, and there are endless ridges of them rolling off into the distance, farther than your eyes can see. Those mountains are so much bigger than you, and they have no wants, no needs. They are not eaten up with longing and sorrow. They do not know desertion or loneliness. They just are.

That is where you want to get. You want to trust that no matter how loud and angry and burning your need is, it is nothing compared to the wide world. You want to believe that God will provide for you, to temper your desire with the promise of peace. Surely, if God can take care of those mountains, he can take care of you. You have to let him. You have to tell him that you’re ready to let him.

You, having had a spiritual awakening through Jesus Christ, will try to carry this message to all those who suffer from addiction.

Q. Can dwelling in the word of God in thought and deed truly prevent you from succumbing to your addiction?

The truth is, you hate this place. The refuge isn’t much more than a reeking warehouse. You hate lining up for the meals like a child at school, hate standing in a corner while the staff look under your mattress and in the pockets of the shirts your wife sends you, hate sharing a room with an illiterate and toothless meth addict who needs you to read him his daily Bible verse over and over again until he can memorize it.

They tell you that this is what it means to dwell in the Lord, to devote every waking minute to learning his word and divining his will and praising his goodness. It’s hard work. Maybe the hardest of your life, and there’s nothing pleasurable about it.

Sometimes you think of giving into the longing. One smuggled can of beer from your rare trips to town would be enough. You’d be free. You hate the regiment of it all, the predictability. You have always preferred standing on the edge of the cliff, playing the daredevil, leaning out farther and farther over the abyss.

Across the street from the refuge, on a hillside in view from dining room’s big picture window, is a cemetery. When the craving is at its worst, when the tedium sets your teeth on edge and your head to pounding, you look up there. You know what’s waiting for you at the bottom. You know how close you came to falling.

You wouldn’t say it to the Pastor – he prefers positive thinking – but you have a feeling they built that picture window with that view in mind.

Q. How can you practice Jesus’s commands when they are so different from what you are used to?

What scares you most is the thought of life outside this place again. There are no drugs here, no open bars, few choices. The rules are very clear. The ways you can fail are spelled out for you, and all you have to do to make it each day is exactly what you are told to do.

But when you’re done here, when they hand you your certificate of graduation and they bless you and pray for your future in a circle of brotherhood, you’ll go out and you’ll have to start again. And you are afraid, not so much of how you might fail but of why.

You’re afraid of just how boring life really is. When you were using and drinking, when you were teetering on the edge of oblivion all the time, when everyone you loved was afraid for your life, it was terrible, yes; but it was also exhilarating. You were the star of your own show, the center of attention, the instigator of constant prime-time drama.

Each day you think of something else that’s waiting for you out there. Job applications, rude customers, worn-out brake pads, headaches, lost keys, colds, lines at the bank, termites, dog shit on your shoes. Before, you chose not to handle those things. You got high instead. Now you will have to learn to deal with all of it, and at the end of the day no one will congratulate you for patiently waiting to use the ATM or remembering to turn down the heat at night to save on the gas bill.

Each day you’ll have to make a thousand choices, over and over again. To serve God and not yourself. To honor your family and not your addiction. To turn the other cheek instead of striking with a raised fist.

Even Saint Thomas had his doubts.

Once you leave, they will not let you back into the refuge unless you stay clean. There are no second chances here, no allowances for relapse. But they do expect you to come back to testify to your new brothers in Christ about life after salvation and recovery. You will have to stare into the thin, wrecked faces of men struggling to make it through each minute. You will have to pray over them as if you can speak with God’s authority.

You know that they will look up at you, the survivor, and ask you if what you have is worth it.

And how will you answer?

What will you say?

Q. If you are born a sinner, and even your “good” deeds are born of sin, and it’s sin you love anyway, and God hates and condemns sin – what hope is there for you?

A.

AFTER COMPLETING THE WORKBOOK AND YOUR BIBLE STUDY, BUT BEFORE YOU GRADUATE FROM THE REFUGE, PLEDGE THE FOLLOWING FOR YOUR SALVATION, SOBRIETY, AND SECURITY:

I realize that I am a lost sinner who needs forgiveness and salvation. I believe Jesus wants to forgive me as the Bible promises, so here and now I give him my life. I pledge to follow him in Word, Thought, and Deed; I confess to my addiction, my sins, and my weakness, and will overcome them through the Blood of Christ.

Signature

Date

BIO

Clarissa Nemeth is originally from Gatlinburg, Tennessee. She has a Bachelor of Music degree from Boston University, an M.F.A. from North Carolina State University, and is currently a doctoral candidate in creative writing at the University of Kansas. She primarily writes about individuals and communities in Appalachia and the New South and is working on a novel about the tourist towns of Sevier County, Tennessee. She lives in Lawrence, Kansas with her husband Greg and their pit bull, Boogie. This is her first publication.

Clarissa Nemeth is originally from Gatlinburg, Tennessee. She has a Bachelor of Music degree from Boston University, an M.F.A. from North Carolina State University, and is currently a doctoral candidate in creative writing at the University of Kansas. She primarily writes about individuals and communities in Appalachia and the New South and is working on a novel about the tourist towns of Sevier County, Tennessee. She lives in Lawrence, Kansas with her husband Greg and their pit bull, Boogie. This is her first publication.

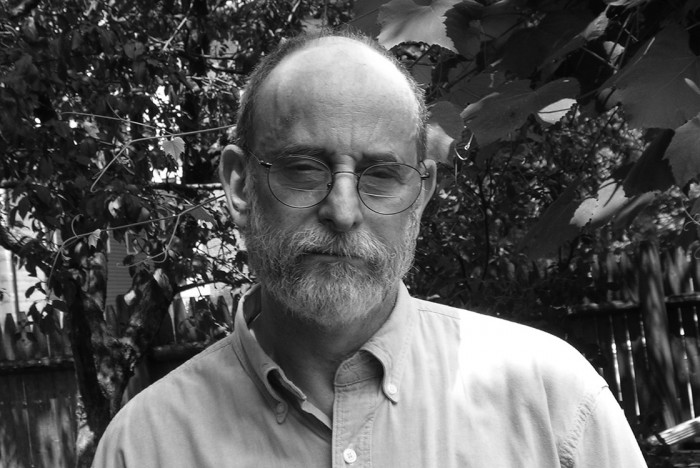

Norman Waksler has published fiction in a number of journals, most recently The Tidal Basin Review, The Valparaiso Fiction Review, Prick of the Spindle, Thickjam. Scholars and Rogues and The Yalobusha Review. His most recent story collection, Signs of Life is published by the Black Lawrence Press. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His website is NormanWakslerFiction.com

Norman Waksler has published fiction in a number of journals, most recently The Tidal Basin Review, The Valparaiso Fiction Review, Prick of the Spindle, Thickjam. Scholars and Rogues and The Yalobusha Review. His most recent story collection, Signs of Life is published by the Black Lawrence Press. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His website is NormanWakslerFiction.com

Bobby O’Rourke is a native of New Jersey, as well as a graduate of both Rutgers University and Union County College. He is currently enrolled in a Master’s program at Fairleigh Dickinson University. He has had poetry published in

Bobby O’Rourke is a native of New Jersey, as well as a graduate of both Rutgers University and Union County College. He is currently enrolled in a Master’s program at Fairleigh Dickinson University. He has had poetry published in

BIO

BIO

A graduate of the Dramatic Writing Program at Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, Joshua Sidley has published short stories in the online journals Fear and Trembling, Kaleidotrope and Bewildering Stories, and the print journal Down In The Dirt Magazine, as well as the online publisher

A graduate of the Dramatic Writing Program at Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, Joshua Sidley has published short stories in the online journals Fear and Trembling, Kaleidotrope and Bewildering Stories, and the print journal Down In The Dirt Magazine, as well as the online publisher

BIO

BIO

Richard Hartshorn lives in upstate New York and earned an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts. His work has appeared in Drunken Boat, Split Rock Review, Hawaii Women’s Journal, and other publications.

Richard Hartshorn lives in upstate New York and earned an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts. His work has appeared in Drunken Boat, Split Rock Review, Hawaii Women’s Journal, and other publications.