Baby Fever

by Pascale Potvin

“We need an ambulance! My friend’s been stabbed and she’s pregnant! Uh … uh … four months!” someone’s cry pierced through my dizzy fog. That’s when I noticed everyone in the kitchen and that they were staring at me. Overwhelmed, I looked down, still clutching my burning belly. My hands were red. Oh.

#

TWO MONTHS EARLIER

“How far along are you?” asked Trish, looking up again from across the table. Her gaze pushed into me like a bulldozer. I leaned back into my chair, insecure about my answer.

“Eight weeks,” I said.

The three women attacked their notepads with their pencils.

Their names were Olive, and Kate (I think), and, in the middle, leading the interview, sat Trish Barton. That woman was all I’d heard her to be. She was blonde, with great skin, and so petite; you could have never guessed that she’d had two children. Nor that they’d been home births. Her kids (a boy and a girl) would probably grow up to be as small as her, too, since she was raising them vegetarian. Basically, she was everything that every Elk Creek mother wanted to be. Already she intimidated me, and she was five years my junior.

“And you’re married?” she asked, with a smile as perfectly tight as the rest of her face.

I’d been expecting to be asked a lot about my living situation.

“Yes,” I answered. “As of recently, uh, his name is James.”

“Oh, congrats. How did you meet?”

“Four years ago,” I said. “He… was at a bar where we were having a company party. I didn’t- uh, I don’t usually go out, and he could tell. He stole me away”. I thought of it, of that image of James in his striped button-up. He’d pulled his sleeves up as he’d approached me, as if telling me he was determined to seduce me–though he’d probably just wanted to show off his arms. I still couldn’t believe I’d fallen for that overgrown frat boy. I chuckled to myself, thinking about it. When I looked back at Trish, though, her face hadn’t moved.

“What do you do?” she asked.

“Uh, I was an accountant for a car company,” I said. “I’m looking for a replacement.”

“And your husband?”

“Yes. He got a job at a hospital in the city, um-”

“Oh. Nice.”

“He’s a doctor.”

Her mouth opened the tiniest bit before she went back to her notepad. I tried to peek.

“And where are you living now?” she smiled up at me.

“It’s a house on Collingwood Street,” I said.

“Oh, so you’re the new owner,” Her high-pitched voice flapped its wings excitedly. Her face had opened up now. A little weird. “Well, lovely, lovely. Will you have transportation?”

“Yes, we have a car.”

“Okay. And how are you liking Elk Creek?”

“We love it,” I said. “We wanted to go somewhere family-oriented. And this was worth leaving, like, everything behind in Michigan.”

“So you understand the purpose of Elk Creek Mothers’ Association?”

I nodded. “Keep the community safe and organize events for moms and kids,” I said.

“And what will you contribute, if you’re chosen?”

I paused, massaging my hands together. Secretly, I hated questions like this; the job hunt was going to be a pain.

“Well, I love children more than-” I started. I was about to say anyone, then I realized that that might not be the best idea, considering who was interviewing me, “-anything. More than anything, I’ve always known I’ve wanted to be a mom, and…” I realized that I probably shouldn’t focus on myself, but on the benefits for the kids.

Trish and her vice-presidents wrote as I spoke. I couldn’t, despite trying, read their notes or their faces.

I told James all about it over dinner. We sat across the width of the dining room table, as the other way might have required us to cup our mouths and yell. I didn’t know why he’d gotten us such a big table, but I supposed that the room allowed for it.

“I’m not gonna get it,” I said, twirling my spaghetti on my fork, then sticking a load into my mouth.

“Of course you are,” he said. “It’s a volunteer position.” He stabbed into a meatball.

“One that everyone wants,” I mumbled, covering my chewing with my hand. “Why do you think I had to do an interview?”

“Is it really this elite thing?” he asked, chuckling and looking up at me. James had blue/green eyes; their color shifted like the tides. In this light, now, they looked a pale, consuming green. He was still so handsome to me with his short, curly brown hair; his thick eyelashes; the quirky asymmetrical-ness of his rectangle face. “But it’s called Ec-ma. Ec-ma,” he continued. “They couldn’t have a prettier name? Makes me think of eczema.”

I laughed until my phone started vibrating on the kitchen counter. I jumped upward, gulped down my noodles and jogged to it.

“Pregnant,” James reminded me.

I ignored him. “Hello?” I answered, in a semi-strangled voice.

“Hi. Lillian? This is Trish, from ECMA,” she said. “I’m calling to offer you membership to our group.”

“No way! Oh, my gosh. Thank you so much!” I exclaimed, looking back at James. He did a double thumbs-up.

“You’re welcome,” she said. “Do you accept?”

“Yes, for sure.”

“Great. Are you available this Thursday at 7:30 PM for our monthly public safety meeting?”

James would be back from work by then. I’d have the car in time.

“Yes, that’s fine,” I told her.

“It’s at the police station. Do you know where that is?”

“Yes,” I lied. I’d figure it out.

“Perfect. See you then,” she said. “Bring a notebook.” And she hung up.

“Told you you’d get it,” James said as I put the phone down. “They loved you.”

I strode back toward him, grinning.

“I admit, I got you something to celebrate,” he said, opening the glass door to the liquor cabinet. I squinted at him as he took out a bottle. “Non-alcoholic cider.” He pointed at the label.

I came closer and kissed him. He kissed me back, grabbing at my arm. He tasted like tomato sauce, and his stubble scratched at my face, but the moment was still nice.

We each had a glass and then we had sex.

When I got up the next morning for the bathroom, I found some blood in my underwear, which James had said was normal for pregnant women after sex. I filled the sink to soak them and then also drew myself a bath. I was nervous for my meeting that evening and I wanted to relax (also, the big tub, with jets, was one of my favourite features of the new house). I sat for a while in the hot, bubbling water and thought of baby name ideas. I’d been thinking of suggesting Madeline if it was a girl, which I was sort of hoping would be the case. Madeline sounded like a girl who’d laugh fervently, who’d love hugs and who would have her father’s eyes.

The meeting went fine, though I was exhausted by the time it ended. I wasn’t surprised; wanting to impress the group was probably piling onto my recent moving stress and crushing me. I went to bed before James that night, but still woke up late the next morning. When I went to the bathroom, I found more blood. Bleeding was normal at this stage, I assured myself. So was the pain in my abdomen. It had happened before.

Unfortunately, both symptoms continued sporadically for the next week, and pretty much non-stop the week after that. The exhaustion was the same.

“Would you be able to get me an ultrasound? For, like, as soon as possible?” I called James on his break the day I decided this was a problem. We hadn’t yet managed to procure a new family doctor, so he would have to play that role for now. I was grateful to have him.

“Of course. How you feeling today?” he asked. I could hear him close a door.

“The same,” I said. I hadn’t left the bed. “I officially think I’m gonna miscarry.” I was going to cry. Neither of us had yet said that word.

“Please don’t worry yet,” he told me in his most caressing voice. “It’s probably stress.”

“It hasn’t been that bad,” I argued, turning onto my side and sliding further under the covers.

“Yeah, but this started as soon as you joined the group,” he said. “That can’t be a coincidence. And…”

“…Yes?”

“I don’t know. Something about that group just kinda weirds me out,” he admitted.

“What do you mean?”

“Like… come on. Everyone here just worships those women. Plus, they’re making you do their bidding, for free, just for the honour of it?” I tried to intervene, but he continued, “You sure you haven’t accidentally joined some sort of cult?”

“In small-town Wisconsin?” I scoffed. Fuck, it hurt to do that. I rolled onto my back, holding myself. “Everything’s normal. Come on. It’s for the community.”

“The way you describe them, they just sound creepy. Are they not?”

“It’s not that bad,” I repeated.

“Really? You sure you’re not hurting and bleeding ‘cause they turned our baby into a demon baby or something? Rosemary’s Babied you up-”

“Stop,” I held back my laugher by the belly. Laughing wasn’t a good idea, either.

“Okay, but admit it. You’re taken by the elitism,” he said, his voice now dipping a little, like a frown. “And that’s what’s weird to me, ‘cause you’ve never seemed to care about that kind of thing.”

“I’m just trying to make new friends here, James. Mom friends. I’m bored and I’m lonely.”

“I get it. But you can do that without this Trish woman, can’t you? How old is she, again?”

“Twenty-eight.”

“Right,” he said. I realized that she was a full decade under him.

“I guess I want my kid to have a good social standing,” I finally admitted. “You know I was bullied.”

James took in a harsh breath. “I understand,” he said. “And I think that’s great that you’re trying to give that to our children, but I think maybe you’re putting too much pressure on yourself. On top of looking for a job-”

My insides fell. “Are you asking me to quit the group?” I asked.

“I wouldn’t do that,” he said, quickly. “Actually… eh, I was wondering…”

They hit the ground. “If I shouldn’t get a job?”

“You’ll be on mat leave soon enough, anyway,” he finally said. “And you know I can support us both.”

I didn’t answer. I only swivelled my jaw.

“Then, maybe later, we can reconsider if you wanna work or not,” he said. “I don’t know. Think about it?”

“Fine,” I said. “But, please, get me that ultrasound.”

James was able to schedule me one for five days later–a Saturday. Unfortunately, I felt exponentially worse by the day. By Friday morning, it was like I had a hole tearing through me. The demon baby theory didn’t seem so implausible anymore.

I wept on the bed, leaving phone messages for James. I took my usual (maximum) dose of Tylenol, and then upped it a bit, but still, not much changed. When I finally struggled my way out of bed, I noticed that I’d left a bloodstain. I went to the bathroom and took off my clothes. I felt so weak and vulnerable, even nauseous, so it took a while. I ripped the pad off of my underwear–which, along with my pajama pants, had been stained, nonetheless–and threw it out. At least none of the blood seemed clotted.

I managed to make myself a hot bath, with jets. Once I got in, it helped the pain, a bit, but it worsened the nausea and the exhaustion. When I got out and checked my phone, it was still only nine o’clock. I had no idea if James would get my messages before his break.

I went back to the bed, in my bathrobe, to sit and try to think of what to do. If we’d been back home, I would have called a cab to the hospital, but there were none in this puny town. I could call an ambulance, as it’d come faster than a cab would from the city, but that seemed excessive. I would just have to make it a few hours. There was no way I was contacting ECMA, either; they couldn’t know that this was happening. I had just been accepted. I’d already forced a smile and gone to the last two meetings.

I changed into new underwear with a new pad, and new pajamas, then lay back down. Just a few hours.

It was easier thought than done, though. I held myself on the bed and cried for about thirty minutes until I gave in and lugged myself to the dining room.

“Forgive me,” I rasped, pulling out a bottle of scotch and a glass from the liquor cabinet. But she was probably already dead. I poured myself a glass then the contents down my throat. The burning it caused distracted from the burning in my abdomen. I poured another.

I was disoriented when I heard James yell, “What the fuck is this?!”

I lugged my head up from my arms, wiping my mouth. I looked at my hand. My saliva was brown. I looked to my right. James was standing next to me. I was still sitting at the dining table. I’d fallen asleep. I’d never fallen asleep at a table like this.

“Is this why this is happening? Is this what you’ve been doing during the day?!” he continued. I looked up at him. He was sneering, his eyes burning hell into me. I’d thought that I’d already seen him at his angriest, but apparently I hadn’t even seen him close. “What kind of mother are you?!”

“No,” I groaned. “Have… you found me like this before?”

“Well, I don’t know,” he said, leaning down further into me. “You’ve been really emotional-”

“Because I’m in fucking pain and I’m fucking losing my baby,” I said. I strained myself up straighter, but my head was spinning. “I need the hospital.”

He stared into me for a few seconds. His eyes had gone paler, colder. “No,” he said.

My heart jump-started. “What the f-” I tried.

“You’re not going anywhere. They can’t see you like this. Even if you’re not a drunk, they’ll think you are.”

“It’s… not… optional.”

“Sure it is,” he said. “Didn’t you want a home birth so bad? Like what’s-her-face? Have a home miscarriage.”

Then, he passed me for the kitchen. I put my head back on the table and cried again.

The pain woke me up before James the next morning. I heaved myself over to the bathroom–a ritual now–and the usual blood was there. I started to undress when I was taken by nausea.

I sensed James walk in behind me puking.

“Hungover?” he snarked.

“Please,” I whimpered.

I got changed, and he drove me, in silence, to the hospital. It was in the car seat that I started to really feel the bleeding. Feel it get thicker.

After the painfully long drive, I was given away to a Dr. Schuster, a middle-aged black woman with black ponytailed braids. She helped me put on a hospital gown, and she set me down on the plastic bed. I was shivering. I covered my eyes as she checked me. I felt her clean me. It was cold. But there was no colder feeling than the one in my belly–and, though I knew that it was just fear, it also felt an awful lot like a dead baby.

“I’m so sorry. You did have a miscarriage,” she said, standing over me, dropping each word down gentler than the last.

But it doesn’t matter how gently you drop a child’s corpse onto her mother’s face.

She might as well have dropped a boulder on me, I thought. And, in that moment, I wondered what my daughter looked like. She’d probably resembled red, thick lava when she’d been ejected from the center of my core–but now I was a volcano with no purpose left, and now both of us were cold.

“I’m gonna give you an ultrasound to make sure there are no further complications and that you’re safe,” Dr. Schuster said, and I grimaced. I was grateful, at least, to have her instead of James.

“It still hurts,” I grumbled, lips dry.

She had me open the front of my gown. She put the ultrasound gel on my belly then felt across it with the stick.

“Is it all out?” I muttered.

“Actually…” she said, her voice shaking now, “I’m going to have to put you into surgery.”

“Why?” I rasped, sitting up quickly and wincing.

“You’ve had an ectopic pregnancy.”

I hadn’t heard of that before, which wasn’t a good sign.

“Your egg failed to travel through your fallopian tube,” she explained. “Your foetus has been growing in there, and now it’s burst it. You’re bleeding internally and… your other tube might have been damaged, too. I’m going to have to go in to try to save it.”

Everything, then, felt like it was spinning and shifting. Probably because everything was. I erupted, again, this time with tears.

When I woke up in a hospital bed, I tried to shoot up straight. My abdomen cried out in pain, and so did I. I remembered that I’d had surgery. A nurse called for Dr. Schuster, who entered shortly after.

“Can I have kids?” I mumbled.

“I’m so sorry, Lillian,” she said, her face struggling to stay adrift. “It’s not likely you’ll be able to conceive. Your tube was badly ruptured, and your other one was…”

I tuned her out, then. I retreated all the way under the covers and closed my eyes.

When I was more awake, she gave me and James the instructions for my care.

“No working for eight weeks,” she said. “And absolutely no sex.” Her expression had finally given up and died now. So had mine. It had gone down with my baby.

My baby had died and taken the rest of my insides with her.

James took my hand in his. It was stiff. I looked up at him. He was pale and frozen over. Definitely also dead.

“Again, I’m so sorry for your loss,” Dr. Schuster said to us. “Take your time to grieve, but remember that-”

“Thank you,” James snapped, which made me cringe a little.

And the drive home felt like the one there.

“I called Trish,” he said, breaking the silence, keeping his eyes on the dark road ahead. “Begged her to keep you in the group.”

“Of course she’s not gonna keep me in the group,” I grimaced, picking at a cuticle. “It’s a mothers’ association, and I’m no longer a mother.”

“Well, she said they’d discuss it.”

“I could have done it myself,” I argued, pausing to clamp my teeth together. “It could’ve waited.”

“I thought you might be embarrassed.”

Something about that rubbed me the wrong way. It even struck me.

“Why would I be embarrassed?” I asked, then, in a weakened voice. “…Because it’s my fault?”

He didn’t answer.

“For drinking?” I pushed. “Or for putting too much stress on myself? Daring to look for a job?”

James let out a dense exhale. “I didn’t say that, Lil,” he muttered.

It wasn’t a denial that he believed it, though.

“I can’t believe you think that.” My voice was shaking. “You did this to me, not me.”

At that, he pulled the car over and turned to look into my eyes. But he kept his grip on the wheel. “Excuse me?” he growled.

“You’re a doctor. You know what an ectopic pregnancy is, James. You know it was failed from the beginning. When your sperm entered me and ripped me up slowly from the inside.”

I watched the anger bubble up inside him, then. “You don’t mean that,” it finally escaped as a chuckle. “You still have those hormones going.”

“Hormones?! I just lost my purpose in life.”

“So did I!”

“But you’re not the one who had to just go through that,” I screamed, the hairs on my arms rising with my voice. “Have some humanity! I just want my husband to comfort me right now, not fucking attack me!”

But all he did was turn back toward the wheel. He stared again at the black nothingness ahead, and it reflected in his eyes. We sat there, listening to our own hard breaths, until he finally spoke again.

“Humanity is defined by the ability to reproduce, isn’t it?” he said, and he turned the car back into the road.

I was too stunned to even respond. Had he just implied what I thought? Had my husband just diagnosed me with not being human anymore?

I was taken by rage. He had done this to me.

The continuing, torturous silence was shaken, thankfully, when my phone vibrated at my feet. I struggled, aching in every sense of the word, to pick up my purse and retrieve it.

“Hello?” I groaned.

“Lillian? This is Trish,” came Trish’s glossy voice from the other side. But she also sounded a bit more genuine, more normal now. “I wanted to say that I’m so, so sorry to hear about what happened. I can’t imagine what you’re going through.”

I know you can’t, I thought.

“Thank you, Trish,” I said. “I appreciate it.”

“Do you need some time to yourself or do you have it in you-”

“Just lay it on me.”

“Okay. Well… we talked about it for a long time. It was difficult. Because we could really feel how passionate you are about the association, and we’ve appreciated having you so far. So… we actually came up with a possible compromise, if you’ll accept it.”

I felt the littlest fragment of life return to me.

“What kind?” I asked, leaning against the window.

“So, we have an official Facebook page, you might know. I like to keep it active, to attract attention. Like, post some content a couple times a day. But I wouldn’t mind that job being taken off me, if you want it,” she said. “It seems perfect for your… situation. You’re homebound, correct?”

“Right.”

“Well, since it’s online,” she said, “You won’t have to leave home to do it. And… since you’ll be behind a computer, and no one can tell who’s posting, anyway, no one will tell that you’re…”

“Not pregnant,” I said. It was such a pity offer, but I still appreciated it. I couldn’t believe that Head Mom Trish Barton was being more forgiving than my husband. “So… I just have to post as if I were pregnant? Or a mom?”

“Uh, exactly.”

“Well, okay,” I said, and then took in a cold breath. “Thank you… so much.”

“No problem. I’ll e-mail you more details in the morning, and you can let me know when you’re ready to start. For now, get some rest and feel better.”

“Thanks.”

The next morning, I went to the office computer and indeed found an email from her.

Hi Lillian, it said,

If you go to Facebook you’ll see I made you an admin for our page. That means you’ll be able to post to it under our name. Take a look at the past content, if you haven’t already, to get an idea of what kind of stuff is good. Articles about parenting are great, as long as it’s not ‘disciplining’ tips or anything too aggressive like that. Also please look for funny ‘memes’ about motherhood. Basically just fun, light-hearted stuff. Oh, and add appropriate captions, please.

Posts should go up once every morning and once every afternoon. You can start whenever you feel ready. Just let me know when that is and I’ll leave it to you 🙂

Take care,

TB

I can start today, I wrote her, or I may die of boredom.

I went on Google and looked up ‘parenting article’. I clicked on a page titled What to Expect When Your Child Starts Kindergarten.

It opened with an image of a mother and daughter smiling together.

Oh … god.

- You’ll want to keep track of all of the school activities and meetings and help out when you can, it said.

- Making friends with other parents will be a huge stress-saver.

- Your child may cry because they’re scared or because they miss you, but that doesn’t always mean that they don’t want to be at school.

- Your child will be a lot more tired than before. They may start to fall asleep in weird places. It will be cute.

As I read, the pain where my baby used to be flared up like a phantom limb. I couldn’t do this. I hadn’t realized how difficult this would be.

ECMA definitely didn’t realize it, either, though. They had been so kind to find this job for me. If I didn’t do it, I had nothing left.

I decided to just try a different route. I exited the article and Googled, ‘Mom memes’.

The first image was a simple illustration of a woman, accompanied by the text, That moment when you’re checking on your sleeping baby and their eyes open so you run before you make direct eye contact.

My eyes swelled and my hands contorted. Just hurry up and post it, I told myself, then you can go wallow under your covers again. I saved the image and put it up on the Facebook with the caption, Haha, I hate when this happens!

Pressing every key was like stabbing myself over and over.

I was still under the covers that afternoon when I heard James unlock the door. Thankfully, he fussed around cooking in the kitchen for a while before approaching the room.

“Lil?” he mumbled. “I made dinner.”

My brain foggy, I forced myself to get up and follow him to the dining room. He helped me sit down at the table. He’d set out steak and potatoes for us. Plus, a bottle of wine, with wine glasses. He offered me one.

“Thank you, the food looks amazing,” I said, “But not right now.”

“Why not?” he asked, uncorking the bottle. “You can drink it now.”

I stared into my lap and ran my tongue between my teeth. “What is this?” I finally asked, my voice sharp.

He sighed. “I wanted to make it up to you, after last night,” he admitted. “You were right. I shouldn’t have been fighting with you.”

I sighed, too, nodding. I was still hurt by what he’d said, but I didn’t want to bring it up. Clearly, he didn’t either. So we made dull conversation about his day as we ate. I avoided talking about mine.

When we finished, he took away the dishes and I went to the living room couch.

“What are you up to tonight?” he asked, entering from the kitchen behind me. “Want to see what’s on TV?”

“Could you get me my book?” I countered. “In the bedroom?”

“Sure,” he said. Then, “Why don’t you read in there? You’ll be warmer.”

“I guess, but I’ve been lying there all day.”

“I could help entertain you,” he said. He came up behind me and rubbed my shoulder.

I turned, looking up at him with a grimace. “You know I can’t have sex, James.”

He chuckled. “I mean, it’s actually not that big of a deal-”

“Except I’m really not up for it. In any capacity.”

He paused. “Okay, okay, just trying to be close with you,” he grumbled, before walking away.

Of course, I was going by what Dr. Schuster had told me–and James, as her peer, should have known better–but, in truth, I was most resistant for my own reasons. I just could not get that image of James’s invasive, destructive sperm out of my mind. I did not want his semen anywhere near me anymore, after what it had done to me. I was disgusted by it, by the very idea of sex with him.

Unfortunately, throughout the next few weeks, James continued to try to initiate it with me. And, as I continued to say no, he continued to get grumpier. Funnily enough, I couldn’t remember him ever being this horny before. It was interesting that he wanted to fuck me the most now that he didn’t consider me human.

Eventually, he got the message and he stopped pushing. In one sense of the word, that is. Instead, he began to push himself, sometimes, onto my healing abdomen while we were cuddling… to even, some nights, knee it in his sleep. But I suspected that he wasn’t asleep.

When I would go to the computer to post for ECMA, in the morning, I also started to find paused porn videos left open on the computer. I understood that James needed to get his urges out, somehow, but, like the kneeing, it happened just a little too often to seem truly accidental. This was another expression of frustration at me, then. James was rubbing in my face that I wasn’t satisfying him. He was showing me exactly who all of the younger, hotter women were that were getting him off.

I only really started to become afraid when the porn started to get violent. I would go to the computer to find images of women–though that wasn’t what they were being called, in these video titles–being stepped on, hit with things, choked. Their faces always showed distress or discomfort, and when they didn’t, it was because they were being shoved into a bag, trashcan, or toilet. At that point, I shouldn’t have been surprised that this was the kind of thing that James was into. But I felt that this porn might have become more than just a taunting… had it also become a threat?

I cried a lot during those weeks. Fearing for myself, what he might do to me in my sleep, I locked myself in the bathroom at night and slept in the tub. Weirdly, he never challenged me for it. He acted like everything was normal. He’d ask me how I was feeling. I would tell him everything was great, and he’d smile.

When I went in for my first check-up with Dr. Schuster (Aileen, she said to call her), she told me that I was behind in my healing. It was most definitely the kneeing, I knew. But I realized what I had to say.

“We had sex,” I told her. “I’m sorry.”

She shook her head. I felt a heavy shame for disappointing her, even though it had been a lie.

“I understand you want to try again,” she said, sitting down at her chair across from me. “It’s common for couples in this situation to have trouble dealing with it, at first.”

I wrung my fingers.

“I hope this isn’t intrusive for me to say, but… your husband has seemed depressed lately,” she continued, her wide face dipping a little. “He’d mentioned how many kids you two wanted… so I wanted to ask you how you’re doing, mentally.”

I looked back into her eyes. James and I had never actually talked numbers. Both of us adored kids, of course, but it had made sense to me to just take it one at a time.

I almost said nothing. “How many kids did we want?” I decided to ask. It came out grumbly.

“Pardon me?” asked Aileen.

“How many did he say we wanted?”

“Well… he’d said at least eight.”

I felt so heavily confused and disturbed, in that moment, like I could fall over–like she’d reached out and slapped me. Eight kids? Eight? Where the heck had he gotten that idea? My personal limit would probably have been half that number; why did he go around saying something so outrageous, when we’d never even discussed it?

I had an itch of a thought, and so when I got home, I did my own personal Googling. One of the results included a page in a women’s health blog, What is Reproductive Coercion?. I dismissed it at first, but the title kept chipping at me until I went back and clicked on it.

Have you ever heard of men obsessed with getting and keeping their partners pregnant?, the author wrote. Chances are that you haven’t. However, new studies have found that this form of domestic abuse is almost as common as are bruises and broken bones. Whether subtle or forceful, it is just another form of power and control that a man can exert over a woman’s body and life. He may be performing reproductive coercion if he:

- Sabotages your birth control. Maybe he’s lied about having had a vasectomy, or he ‘accidentally’ keeps ripping the condom, or he tells you that your birth control is making you fat. He might even escalate to doing something like rip out your contraceptive ring.

- Isolates you–limits your access to money and transportation. It may also be a strategy to prevent you from acquiring birth control. Or maybe he wants you to quit your job so that you can focus on being a mother (and be totally dependant on him). Isolating you can also prevent you from getting refuge from your family or friends.

- Verbally, psychologically and/or emotionally pressures you into having sex and/or getting pregnant.

- Uses violence or threats of violence to pressure into having sex and/or getting pregnant.

- Wants you continuously pregnant. He may attempt to make another baby either directly after you give birth (or miscarry), or as soon as your previous child begins kindergarten (and your schedule opens up).

A stinging, tingly feeling surfaced in my limbs as I read. It gradually got stronger, then moved to my core.

I sat, paralyzed, thinking back to the beginnings of my relationship with James. He’d been upfront about his traditional leanings, his need to get married and to have kids. I’d found it endearing, romantic—as I had his eventual suggestion that we run away together. Men with a passion for children are attractive to many women, including myself. And, because I’d shared his passion, I suppose that I had never had to face his wrath. Until now.

As Aileen had suggested, he was probably refusing to accept that I was now infertile. His obsession with sex was probably a desperate, delusional attempt to get me pregnant again. Either that, or he was panicking and trying to control me in other ways.

I almost scoffed at the predictability when I came to the computer, one morning, and found ‘pregnant woman porn’. Of course James had this fetish. And of course he was going to go down this road; this was the ultimate taunt, the ultimate display of what I could never be for him.

I should have grimaced and closed the tab as quickly as possible, of course. That was what I usually did. This time, though, something different happened. I stared at the image. Really stared at it.

The woman was leaning on all fours, her eyes jammed shut and her mouth agape, her inflated belly dangling pathetically. Her hair, a mess, fell partially in her face and was pulled partially back by the man fucking her from behind. I hit play on the video. The words suffer, you pregnant bitch clotted together in my mind.

When I finally did close the tab to get to my Facebook responsibilities, my bitterness lived on. It always did, when I did this work. This time, though, it was even more intense. It filled the room, now. Plus, now that it knew what revenge felt like, it wanted more of it.

I had a few notifications from comments on my latest pregnancy meme–one that had especially made me feel like killing myself. They were idiotic, tart messages like ‘sooo truuueee’ and laughing faces; god, I pitied these women’s children. Rage spiralled in my stomach, flashed underneath my skin as I stared down their profile photos in the same way I had the woman in the video. Their big bellies and smiling husbands made me wish upon them the same fate. I wanted, so horribly, for them to feel that humiliation for being pregnant. That trauma.

I realized that maybe I could get them close.

I logged out of Facebook and created a new account under the pseudonym Joe Coen. I then went back to the ECMA page and to the profiles of frequent commenters. I composed a message, which I sent to all of them:

Here’s where I’d like to see you soon 🙂

And I attached the porn link.

A few hours later, I received a call from Trish. When she said we needed to talk, my inner sanctum–the satisfaction I’d made for myself–imploded on itself. She knew that it had been me. Somehow. How? It made no sense how she would. Yes, I controlled the Facebook page, but it was also accessible to everyone. And the world was not short of misogynistic men who sent messages like that.

It was probably a coincidence, then. This was about something else. Still, the worry would keep me up all night if I didn’t talk to her today. I asked her to come over, preferably before my husband came home.

The low look on her face, when I opened the door, made my worry flare up worse. I invited her over to the kitchen. Her steps were careful. I was definitely in trouble. My mind ran in zig-zags, debating what to do.

I offered her a seat at the counter, and, when she denied a drink, sat across from her. I forced a smile. I decided that unless I was offered undeniable proof that she’d tracked me down, I would do just that–deny.

“So,” she said. She was still avoiding eye contact. She rested her French-tipped hand on the counter and cleared her throat. “I don’t know if you heard, but a lot of women from our Facebook received a really nasty message this morning.”

I widened my eyes and gasped. “Oh no,” I said. “Did you want me to do something?”

“That’s not why I came, no,” she said, and she finally looked back at me. “I’m here to ask you to tell me, completely honestly, if it was you.”

Her eyes pressed into me like a drill, making me shake.

“W-why would you think it was me?” I responded. Acting had never been a thing of mine.

“Because I had a miscarriage once,” she said.

My shock, then, was real.

“Surprise,” she chuckled, baring teeth. “Yes. I was pregnant once before Noah, and no one knows except my husband.”

“I’m sorry-”

“Don’t. I’m just trying to make a point,” she said, resting both arms on the counter now. She was shaking, too. “I had become such a mess, y’know. I hid it well, but I was super depressed for about six months, and… angry. Like, I hated pregnant women… moms in general. I had thoughts that… and, my therapist–yup, I have one of those, too–told me that that can happen when you miscarry.”

I swallowed, gripping my shirt.

“And so I can’t imagine how much worse it might be, for you, because…” she continued, pursing her lips and speeding up her blinking. “I thought about it today, and maybe having you do the Facebook may not have been the best idea. Right?”

I put my head down and nodded.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” she asked. “If it was too much-”

“Because… I need… “ I struggled, putting my face into my hands.

“Do you have a support system?” she asked, quieter now. “Your husb-”

“Is that a line from your therapist?” I retorted.

“Maybe,” she said. Do you want his number?”

I looked back up at her. Chuckled. “Maybe,” I said, crossing my arms. “Now that I’m out of the mommy group. Now that everyone’s gonna hate me.”

She shifted in her seat.

“How about this?” she said. “I’ll keep your secret if you keep mine.”

I found myself leaning back toward her. The heavy look in her blue eyes was filling me with some hope.

“And… I understand that you need friends right now. So, even though I’m gonna have to kick you out of the group…” she continued, “You can still come to our social events.”

“…Do I have to pretend to still be pregnant?”

She paused. “No,” she said. “That would be cruel. And… weird. And people would figure it out. Besides, they’ll understand. I’ll just warn them about your situation, if that’s okay, so that they don’t say anything… uncomfortable. But we’re capable of socializing with people other than mothers. We could even use it.”

I thought about it. “I don’t know if I’d be able to handle it, honestly,” I said.

“Well, you can leave if you really need to. But I really think that if you get to know them, you’ll hate them less.”

“Is that what worked for you?”

She nodded. “We’re having bake sale Sunday afternoon,” she said, then. “I could use some extra hands. Would you be able to help, or are you still out of commission?”

“I should be, but I really need to get out of the house.”

“Great.” She actually smiled. “Most of the women you sent those messages to will be there. I hope that you can make friends.”

That hot, sunny Sunday afternoon, I drove up to Trish’s place early. It was tall, multi-sectioned, with lots of big windows and a fancy BMW parked out front. As soon as I saw it, I sped up and drove down a couple of blocks to park. Then I remembered that I was also driving a BMW. I took several deep breaths.

Once parked (closer, now), I reached, with some pain, for the pan of date tarts in the passenger seat. I strained my way with it to her door. I had been expecting to see a table or two on her lawn for the bake sale, but there were already several rows of tables propped up, ready to be used. This might as well have been a baked goods convention.

The door was partially open, but I knocked anyway, and soon heard the approaching clacking of what sounded like wedges.

“Lillian! You came,” she exclaimed, with her IKEA-white smile. She was wearing a purply sundress and had done herself up all nicely. “You’re the first one here. Come in!”

I handed her the pan and she thanked me and led me to her kitchen. “I’m about to start putting things out,” she told me. I walked behind her through her large, wood-and-stone living room; her little boy and girl were playing quietly in front of the fireplace. Seeing them gave me a flash of cold.

The kitchen was more modest and cozy. The floor was yellow tile. To my left was a wooden table cluttered with baking supplies. Trish went around it to the counter against the wall. A multi-colored curtain hung on the window next to her.

“Oh, good, Rick put in the muffins,” she said, peering into the oven. My body tensed.

I got worse as more mothers arrived. Trish figured that I should be sitting down, because of my healing, so she set me up at one of the tables to sell things. That meant that I was approached by all of the moms wanting to offer something and those wanting to buy.

I tried to make conversation, and get to know them, like Trish had suggested–I really did. Unfortunately, my anger rattled so loud in my brain that I could barely hear anything that they said. When I tried to talk about myself, my jaw remained so tense that it barely even worked. It was pathetic, trying to speak. The woman across from me would always end up walking away in silence. That made me more irritated, though. Trish had told them what I was going through.

So, like the nauseating smell of the melting icing, every new addition to the party further constricted my throat. Every new belly, every new child on that lawn took more air out of me. The sights became too much. The conversations–about the school, about bedtime routines, breastfeeding–circled around me like hyenas. The laughter–fuck, especially when it came from a child–sounded like the ugliest cackling.

I found myself wishing agony on the pregnant women, especially. Stretch marks, saggy breasts, vaginal stretching–things that could lead their husbands to cheat on them. That cheating would mess up their children so bad that they’d become drug addicts and criminals. Yes. That would make me feel better.

The baby in my belly had, at this point, been officially replaced by a solid mass of pure fury. And, unlike my baby, this fury had a heartbeat, which I felt pulsing hard through my body. Unlike my baby, it was twisting, crying, and kicking.

“Are you doing okay?” Trish’s voice came floating above me. Suddenly I was back in the world. Self-conscious again.

“Yeah,” I managed, looking up at her.

“You don’t look it. No offense.”

That’s when I realized how sweaty I was. And also that I was shivering. Like a sick woman.

“This may have been too much too fast. I’m sorry,” she said. She waved me up and then led me back into the house. “Eliza, can you take over for Lillian?” she yelled. Once we were out of the sunlight, and away from all of the bodies and voices, I found myself gasping for breath.

“Do you need to lie down?” she asked me.

“No. Let me do something else,” I pleaded, heaving. I was still holding onto a stupid slice of hope that I could make it back into the group, one day. I needed to prove that I was still mother material–not just another child to be taken care of.

“Okay… well. I just made another cake. Maybe you can help me decorate it.”

I nodded, but cringed a little when we found Kate in the kitchen. I knew her from the group and from Facebook. She was young, Italian looking. Thick eyebrows, small belly.

“Hey! Glad you could make it,” Trish said to her.

Kate nodded. “I was just looking for you,” she said. “Sorry I’m late.”

“Right. How dare you have an ultrasound?” Trish giggled. Her smile then left and she got quiet.

Keep cool, Lillian, I thought. Please.

Kate looked at me. “Is everything okay?” she asked. “You two kinda rushed in here.”

“Uh-huh,” said Trish. “Lillian was just overheating.” In a sense, not a lie.

Kate and I smiled at one another, but as her eyes dug into me, my embarrassment deepened. She was definitely wondering if this had something to do with my miscarriage. There was nothing I could do to stop her from wondering it. I looked away and focused hard on the wall above the stove.

Trish walked to the oven, then, to take out the cake. She moved it from its pan onto an embroidered plate and then placed it on the table.

“It’s strawberry shortcake,” she said. “Just needs some whipped cream and strawberries.”

“Do you need any more help with anything?” asked Kate.

“Don’t worry,” said Trish. “Unless you want to help me clean up.”

Kate did. The women cleaned, chatting, as I sat silently decorating and trying to recover. Now that I felt like I had some breath back in me, my inner fire had, thankfully, blown out. The foundation to it was still there–a gaslight that could easily ignite another flame–but, for now, I was sane enough to question all of those horrible thoughts I’d been having. I held back tears.

“Lillian?” Trish ended up saying. Fuck, she’d noticed. “Are you alright?”

“Yes,” I tried to say.

“Do you want to call your husband?”

“No,” I demanded. Too quickly. A tear finally escaped. Child. I was a child. “He’s busy,” I said, in a diluted voice.

“Is that why you didn’t invite him today?” she asked, taking the seat next to me.

“Yes,” I managed, standing up. The cake looked good enough now, but I needed something else to give me an excuse not to look her in the face. I grabbed a knife from the other side of the table and started to cut it up.

“Lillian,” Trish protested, placing a hand on my arm. “If something was going on at home, you could tell me. That’s something we do for women here. We help. You know that.”

I stopped moving but the knife shook hard in my hand. Hers felt like soft tissue. I found myself turning towards her.

“Is it okay if Kate stays?” she asked me, slowly.

I nodded, swallowing some tears and snot. I had to accept it. I was still that sad little girl who just needed some friends.

Kate approached me with softened eyes.

“Sit back down, love,” she told me, placing a hand on my shoulder. “Tell us what’s wrong.”

I nodded again. Sniffing, shaking, I started to sit, and I reached to put down the knife.

“Have a piece of cake,” Trish told me.

“Yeah!” said Kate. “Or- I brought madeleines.”

BIO

Pascale Potvin is from Toronto, Canada, and has been writing since childhood. She is currently working on a budding book trilogy. She has also just received her BAH in Stage & Screen Studies from Queen’s University, where she has written a few award-winning short films. Some of her blog pieces can be found at onelitplace.com, where she works as an assistant.

Pascale Potvin is from Toronto, Canada, and has been writing since childhood. She is currently working on a budding book trilogy. She has also just received her BAH in Stage & Screen Studies from Queen’s University, where she has written a few award-winning short films. Some of her blog pieces can be found at onelitplace.com, where she works as an assistant.

Jeffrey James Higgins is a former reporter and a retired supervisory special agent, who now writes creative nonfiction, essays, and novels. He recently completed The Narco-Terrorist, a nonfiction book about the first narco-terrorism investigation. Jeffrey is represented by Inkwell Management and is currently writing his first thriller. Jeffrey has appeared on CNN Newsroom, Discovery ID, CNN Declassified, and other television programs, radio shows, and podcasts. He has been published in the Adelaide Literary Journal, American Conservative, Trail Runner Magazine, The Washington Times, American Thinker, Police Magazine, and other publications. His recent articles and media appearances can be found at JeffreyJamesHiggins.com.

Jeffrey James Higgins is a former reporter and a retired supervisory special agent, who now writes creative nonfiction, essays, and novels. He recently completed The Narco-Terrorist, a nonfiction book about the first narco-terrorism investigation. Jeffrey is represented by Inkwell Management and is currently writing his first thriller. Jeffrey has appeared on CNN Newsroom, Discovery ID, CNN Declassified, and other television programs, radio shows, and podcasts. He has been published in the Adelaide Literary Journal, American Conservative, Trail Runner Magazine, The Washington Times, American Thinker, Police Magazine, and other publications. His recent articles and media appearances can be found at JeffreyJamesHiggins.com.

John Mandelberg’s short stories have appeared most recently in Prick of the Spindle, Beloit Fiction Journal, Santa Monica Review, and Storyscape. Apparently nobody wants to publish his novels but so what, he’ll keep writing more anyway. He lives in Los Angeles and usually doesn’t like any movie made after 1950.

John Mandelberg’s short stories have appeared most recently in Prick of the Spindle, Beloit Fiction Journal, Santa Monica Review, and Storyscape. Apparently nobody wants to publish his novels but so what, he’ll keep writing more anyway. He lives in Los Angeles and usually doesn’t like any movie made after 1950.

Judy Shepps Battle has been writing poems since long before she became a psychotherapist and sociology professor at Rutgers University. Widely published both in the USA and abroad during the Sixties and Seventies, she deferred publishing to concentrate on career and family. Fortunately, her muse was tenacious and she continued to write during the next three decades filling a file cabinet with scrawled and typewritten poems that are now being organized into chapbooks and individual submissions. The material submitted for publication represents her return to active participation in the writing community. She can’t think of a better way to spend her retirement. Her poems have been accepted in a variety of publications including Ascent Aspirations; Barnwood Press; Battered Suitcase; Caper Literary Journal; Epiphany Magazine; Joyful; Message in a Bottle Poetry Magazine; Raleigh Review; Rusty Truck; Short, Fast and Deadly; and The Tishman Review.

Judy Shepps Battle has been writing poems since long before she became a psychotherapist and sociology professor at Rutgers University. Widely published both in the USA and abroad during the Sixties and Seventies, she deferred publishing to concentrate on career and family. Fortunately, her muse was tenacious and she continued to write during the next three decades filling a file cabinet with scrawled and typewritten poems that are now being organized into chapbooks and individual submissions. The material submitted for publication represents her return to active participation in the writing community. She can’t think of a better way to spend her retirement. Her poems have been accepted in a variety of publications including Ascent Aspirations; Barnwood Press; Battered Suitcase; Caper Literary Journal; Epiphany Magazine; Joyful; Message in a Bottle Poetry Magazine; Raleigh Review; Rusty Truck; Short, Fast and Deadly; and The Tishman Review.

Linda Boroff graduated from UC Berkeley with a degree in English. Her writing has appeared in McSweeney’s, The Guardian, Hollywood Dementia, Drunk Monkeys, Word Riot, Hobart, Ducts, Blunderbuss, Adelaide, Thoughtful Dog, Storyglossia, Able Muse, The Furious Gazelle, JONAH Magazine, The Boiler, Cold Creek Review, and others, including several anthologies.

Linda Boroff graduated from UC Berkeley with a degree in English. Her writing has appeared in McSweeney’s, The Guardian, Hollywood Dementia, Drunk Monkeys, Word Riot, Hobart, Ducts, Blunderbuss, Adelaide, Thoughtful Dog, Storyglossia, Able Muse, The Furious Gazelle, JONAH Magazine, The Boiler, Cold Creek Review, and others, including several anthologies.

Ana Vidosavljevic from Serbia currently living in Indonesia. She has her work published or forthcoming in Down in the Dirt (Scar Publications), Literary Yard, RYL (Refresh Your Life), The Caterpillar, The Curlew, Eskimo Pie, Coldnoon, Perspectives, Indiana Voice Journal, The Raven Chronicles, Setu Bilingual Journal, Foliate Oak Literary Magazine, Quail Bell Magazine, Madcap Review, The Bookends Review, Gimmick Press, (mac)ro(mic), Scarlet Leaf Review, Adelaide Literary Magazine, A New Ulster. She worked on a GIEE 2011 project: Gender and Interdisciplinary Education for Engineers 2011 as a member of the Institute Mihailo Pupin team. She also attended the International Conference “Bullying and Abuse of Power” in November, 2010, in Prague, Czech Republic, where she presented her paper: “Cultural intolerance”.

Ana Vidosavljevic from Serbia currently living in Indonesia. She has her work published or forthcoming in Down in the Dirt (Scar Publications), Literary Yard, RYL (Refresh Your Life), The Caterpillar, The Curlew, Eskimo Pie, Coldnoon, Perspectives, Indiana Voice Journal, The Raven Chronicles, Setu Bilingual Journal, Foliate Oak Literary Magazine, Quail Bell Magazine, Madcap Review, The Bookends Review, Gimmick Press, (mac)ro(mic), Scarlet Leaf Review, Adelaide Literary Magazine, A New Ulster. She worked on a GIEE 2011 project: Gender and Interdisciplinary Education for Engineers 2011 as a member of the Institute Mihailo Pupin team. She also attended the International Conference “Bullying and Abuse of Power” in November, 2010, in Prague, Czech Republic, where she presented her paper: “Cultural intolerance”.

Jim Farfaglia is a writer based in upstate New York. He has self-published three books of poetry that explore themes such as his rural upbringing and a devotion to the pop music of his youth, as well as several local history books. One of them, Voices in the Storm: Stories from the Blizzard of ’66, was a finalist in the CNY Book Awards. His website is

Jim Farfaglia is a writer based in upstate New York. He has self-published three books of poetry that explore themes such as his rural upbringing and a devotion to the pop music of his youth, as well as several local history books. One of them, Voices in the Storm: Stories from the Blizzard of ’66, was a finalist in the CNY Book Awards. His website is

Zachary Ginsburg was born and raised in Chicago and worked there as an educator. He is currently pursuing his MFA in Fiction at The New School.

Zachary Ginsburg was born and raised in Chicago and worked there as an educator. He is currently pursuing his MFA in Fiction at The New School.

DS Maolalai recently returned to Ireland after four years away, now spending his days working maintenance dispatch for a bank and his nights looking out the window and wishing he had a view. His first collection, Love is Breaking Plates in the Garden, was published in 2016 by Encircle Press. He has twice been nominated for the Pushcart Prize.

DS Maolalai recently returned to Ireland after four years away, now spending his days working maintenance dispatch for a bank and his nights looking out the window and wishing he had a view. His first collection, Love is Breaking Plates in the Garden, was published in 2016 by Encircle Press. He has twice been nominated for the Pushcart Prize.

Laura Fletcher studied creative writing at Princeton University; her work has previously appeared in The Nassau Literary Review and Wax Antlers. She has been an educator, entrepreneur, consultant, product manager, and apprentice baker, though is happiest when she is a writer. She currently lives in Denver, Colorado and finds the mountains a great comfort.

Laura Fletcher studied creative writing at Princeton University; her work has previously appeared in The Nassau Literary Review and Wax Antlers. She has been an educator, entrepreneur, consultant, product manager, and apprentice baker, though is happiest when she is a writer. She currently lives in Denver, Colorado and finds the mountains a great comfort.

Eimile Bowden is a recent college graduate, pop culture enthusiast, and avid supporter of the arts. This is her first published piece.

Eimile Bowden is a recent college graduate, pop culture enthusiast, and avid supporter of the arts. This is her first published piece.

Zoë Christopher is a photographer and writer who published her first poem at 16. Soon after she was sidetracked, putting food on the table as an ice-cream truck driver, waitress, medical assistant, addictions counselor, astrologer, art installer, bookseller, Holotropic breathworker, and trainer of psychospiritual crisis support. (She didn’t get paid for milking goats, teaching photography, or raising her son!) She holds a Masters in transpersonal psychology and spent 20+ years working in adolescent and adult crises intervention. Her poems have been published by great weather for MEDIA and WordsDance.

Zoë Christopher is a photographer and writer who published her first poem at 16. Soon after she was sidetracked, putting food on the table as an ice-cream truck driver, waitress, medical assistant, addictions counselor, astrologer, art installer, bookseller, Holotropic breathworker, and trainer of psychospiritual crisis support. (She didn’t get paid for milking goats, teaching photography, or raising her son!) She holds a Masters in transpersonal psychology and spent 20+ years working in adolescent and adult crises intervention. Her poems have been published by great weather for MEDIA and WordsDance.

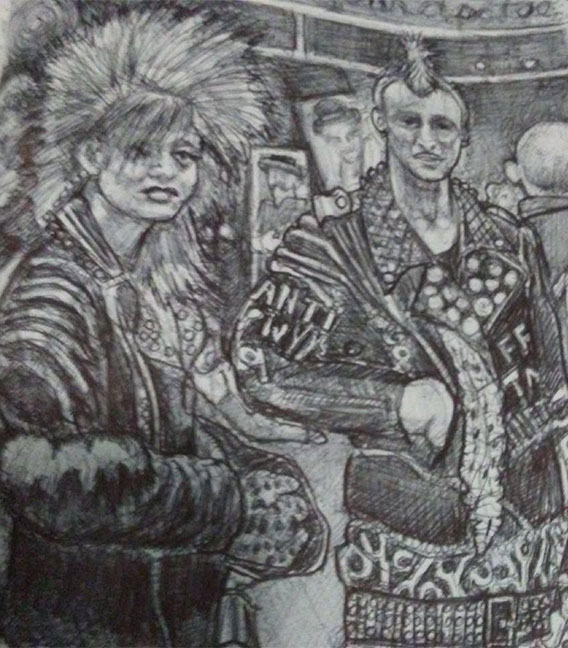

Ashley Urban is a fine artist and illustrator, fashion designer, and visual story teller. Originally from the seclusions of a national forest in Colorado, she has found a strong juxtaposition of culture, sights, sounds and experiences after moving to Los Angeles in 2013. Ashley lives and designs a multitude of creative projects from her downtown Los Angeles studio. One of her favorite pastimes is taking walks through the downtown streets, photographing and studying historic architecture. She has an allegiance for sharing the sights of what she finds well designed, beautiful, strange, mesmerizing or overlooked. With an affinity for bygone eras, she finds considerable excitement and curiosity in the hidden stories that the spectacular historic buildings of Los Angeles could tell. You can find her art, photography, fashion and all manner of the ‘The Art of Style’ on her website, TheAshleyUrban.com

Ashley Urban is a fine artist and illustrator, fashion designer, and visual story teller. Originally from the seclusions of a national forest in Colorado, she has found a strong juxtaposition of culture, sights, sounds and experiences after moving to Los Angeles in 2013. Ashley lives and designs a multitude of creative projects from her downtown Los Angeles studio. One of her favorite pastimes is taking walks through the downtown streets, photographing and studying historic architecture. She has an allegiance for sharing the sights of what she finds well designed, beautiful, strange, mesmerizing or overlooked. With an affinity for bygone eras, she finds considerable excitement and curiosity in the hidden stories that the spectacular historic buildings of Los Angeles could tell. You can find her art, photography, fashion and all manner of the ‘The Art of Style’ on her website, TheAshleyUrban.com

Anastasia Jill (Anna Keeler) is a queer poet and fiction writer living in the southern United States. She is a current editor for the Smaeralit Anthology. Her work has been published or is upcoming with Poets.org, Lunch Ticket, FIVE:2:ONE, Ambit Magazine, apt, Into the Void Magazine, 2River, and more.

Anastasia Jill (Anna Keeler) is a queer poet and fiction writer living in the southern United States. She is a current editor for the Smaeralit Anthology. Her work has been published or is upcoming with Poets.org, Lunch Ticket, FIVE:2:ONE, Ambit Magazine, apt, Into the Void Magazine, 2River, and more.

Megan Mooney is a recent alumni of Miami University where she studied Creative Writing. As an aspiring humorist, Megan likes to inject her comic wit into stories that seek to subvert clichéd storylines. Like many people her age, she enjoys traveling and seeking outdoor adventures. Exactly where she will end up in her career still remains a mystery to her. She currently resides in Lafayette, Indiana, with her family.

Megan Mooney is a recent alumni of Miami University where she studied Creative Writing. As an aspiring humorist, Megan likes to inject her comic wit into stories that seek to subvert clichéd storylines. Like many people her age, she enjoys traveling and seeking outdoor adventures. Exactly where she will end up in her career still remains a mystery to her. She currently resides in Lafayette, Indiana, with her family.

HELLGA’s real name is Olga, and she lives in St. Petersburg. She has drawn since childhood, has no special art education, and is mostly self-taught. As a teenager, she became fascinated with the goth subculture and dark aesthetics. Since then, she’s been drawing portraits of people, fashion illustrations, stickers and prints in her favorite style. She also sews costumes for photo shoots, and makes headpieces and jewelry.

HELLGA’s real name is Olga, and she lives in St. Petersburg. She has drawn since childhood, has no special art education, and is mostly self-taught. As a teenager, she became fascinated with the goth subculture and dark aesthetics. Since then, she’s been drawing portraits of people, fashion illustrations, stickers and prints in her favorite style. She also sews costumes for photo shoots, and makes headpieces and jewelry.

Annie Blake is an Australian writer, thinker and researcher. She is a wife and mother of five children. Her main interests include psychoanalysis and metaphysics. She is currently interested in arthouse writing which explores the surreal nature and symbolic meanings of unconscious material through nocturnal and diurnal dreams and fantasies. Her writing is a dialogue between unconscious material and conscious thoughts and synchronicity. You can visit her on

Annie Blake is an Australian writer, thinker and researcher. She is a wife and mother of five children. Her main interests include psychoanalysis and metaphysics. She is currently interested in arthouse writing which explores the surreal nature and symbolic meanings of unconscious material through nocturnal and diurnal dreams and fantasies. Her writing is a dialogue between unconscious material and conscious thoughts and synchronicity. You can visit her on

Pascale Potvin is from Toronto, Canada, and has been writing since childhood. She is currently working on a budding book trilogy. She has also just received her BAH in Stage & Screen Studies from Queen’s University, where she has written a few award-winning short films. Some of her blog pieces can be found at

Pascale Potvin is from Toronto, Canada, and has been writing since childhood. She is currently working on a budding book trilogy. She has also just received her BAH in Stage & Screen Studies from Queen’s University, where she has written a few award-winning short films. Some of her blog pieces can be found at

Deanna Mobley is the mother of five children. She has worked as a karate instructor for five years and is also an independent study student at Brigham Young University. She plans to eventually write stories and novels for children and young adults. Aside from writing, Deanna also enjoys reading, knitting, and playing with her family. This is her first publication.

Deanna Mobley is the mother of five children. She has worked as a karate instructor for five years and is also an independent study student at Brigham Young University. She plans to eventually write stories and novels for children and young adults. Aside from writing, Deanna also enjoys reading, knitting, and playing with her family. This is her first publication.