Minor League Authors

by Eric D. Lehman

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

– Thomas Gray, “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”

I had written almost every day for more than a decade before someone paid me for it. A European magazine, desperate for content, spotted two of my travel essays on a website and offered me 300 British pounds for them. I eagerly jumped at this offer, feeling ecstatic and somehow justified in my ambitions. Isn’t this how it happened? After all, I had spent my youth filled with a deep and abiding ambition to create words that reached people, to be a respected author like my bookish heroes, to create literature. And it was not a frivolous ambition. I had bent all my energy towards this goal, spending far more than ten thousand hours of preparation, reading ten thousand books and writing over a million words, including two hundred poems, a hundred stories, and four full-length manuscripts. I had earned this payday, and more besides.

However, getting foreign money in the early years of the 21st century was not so easy. I had to set up a special account, talk to my bank several times, and continually badger the magazine editor to pay up. Meanwhile, two copies of the magazine arrived at my door, with my original articles altered completely. Finally, nearly a year later, the money was deposited, but it felt tainted now, flawed and impure. It was as if some forbidden fruit had finally come within reach, but when I took a bite, tasted bitter. Moreover, it was another four years before anyone paid me for my work again.

That feeling of triumph mixed with a rising sense of disquiet was one I would get to know well during the following decade. In those years, my friends and I operated on what we called the Bull Durham theory of authorhood. In the film, written by former baseball player Ron Shelton and considered to be one of the best sports movies of all time, catcher Crash Davis is close to breaking the home run record in the minor leagues. When superfan and adjunct English professor Annie Savoy congratulates him, he scoffs, telling her that it is a “dubious honor” to have a record in the minor leagues. At an author event in 2009, someone said one of my books was a “home run” and I said, “Yes, a home run in the minor leagues.” So, I often felt like the Crash Davis of Connecticut authors, able to keep getting hits with small publishers, mid-range websites, and local magazines.

Even major league authors struggle to earn enough money to survive, and only a few hundred make enough to be called rich. Still, a major league writer might afford to just be a writer, and not to teach, or live on a spouse’s income, or work as a postal carrier. They might be published by large media conglomerates, but more importantly than that, they are popular, they sell lots of copies, they get lots of grants and awards, they travel in higher circles: New York, Hollywood, London. As far as royalties and advances, we minor leaguers make almost nothing, and never have. My wife Amy and I supported our author habits by teaching at the University of Bridgeport, at first part-time, then full-time, then tenure track, then tenured, a process that took us both two decades. That was trivial compared to the process of becoming a writer, which lasted a lifetime.

Many major leaguers may not in fact write “better” than some of their minor league compatriots, but the percentage of competent and even beautiful writers in the major leagues is certainly much higher. A few singles made a big difference in your batting average – enough to send you up to the show. Art doesn’t work in quite the same way as sports, though. Just being in the major leagues is no guarantee that the writing will last; many minor leaguers have gone on to be rediscovered, and as many major leaguers have been quickly forgotten.

It took me a while to adjust to this way of thinking. Growing up, my favorite baseball movie had been The Natural, and I had thought I might be Roy Hobbs, the best writer to ever play the game. I believed that some innate talent would carry me to the league championship. Sometime in my late 20s or early 30s I realized that it rarely worked like that. The Bull Durham theory not only made more sense, but it also resonated more deeply, since even as a child I had always had a feeling of being on the periphery, never at the center, never in the thick of art or of life.

That is not unusual. It comes at first from being out of our depth, and later from swimming well without finding the shore. Writing is hard work, much harder than non-writers realize, and most of it is on the front end, learning how to do it properly. “I want to be an artist,” a woman told one of our publishers. “But writing a book seems like a lot of work.” This person asked them how to hire a ghost writer, so she could live the literary life without the decades of struggle to learn how to write. That was one way to solve the problem.

Money or influential connections were others. Unfortunately, or fortunately, depending on the point of view, my wife Amy and I were both solidly middle class. We did not have patrons; we did not study with any elder writers who could lend us an agent or publisher. We had to build a career from home plate to home plate, step by step. But we did have one advantage many writers do not: we had each other. And slowly but surely, we found other minor league authors, editors, and booksellers to befriend, many flowers born to bloom unseen, or at least seen by fewer eyes, than the ones that made the bestseller lists.

And the truth was that almost every author was a minor league author, even those we thought of as major leaguers. At one of our “author parties” at our house, former Connecticut Poet Laureate Dick Allen told us that, finally, in his seventies he had reached the point where journals solicited poems from him. “It’s taken me fifty years,” he said, his flyaway gray eyebrows raised in a sort of half-amused, half-frustrated expression. I got to know that look well during those years, from a hundred writers across the state and beyond.

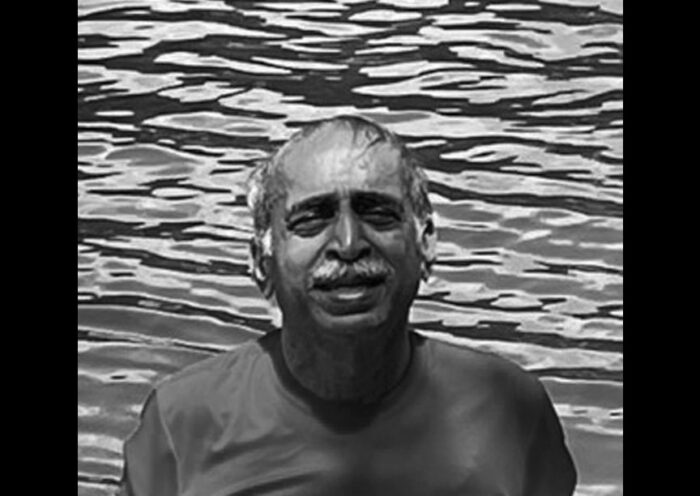

Most of my friends embraced the ideals and the lives of minor league authors. “I’ll be the third base coach,” singer and author Jim Lampos told me once, happily. For him, maybe, it was about building a team. But the person who taught me the most about being a minor leaguer was environmentalist, historian, and poet David K. Leff. When he was younger, he had actually toured many of America’s small-time baseball stadiums and had even sketched out a book on the subject. So, like me, he often talked about going to “the show,” the majors, and about the joys and sorrows of minor league life.

We had met when I invited him to give a presentation for the Hamden Historical Society and had discovered that he knew Dick Allen and other mutual friends. He had also attended a recent presentation Allen and I had participated in for U.S. Poet Laureate Donald Hall’s birthday, energetically moving around the room, taking photos. I thought I could remember him, but couldn’t be sure, and he certainly remembered me. “Your speech was the best,” he told me. It was one of those coincidences of intersection that made for a good story, but later I found out that in his case it was not so surprising. We would meet for liver and onions at a rural diner and inevitably someone would walk in, spot David, shake hands, and exchange news. He seemed to know all the other Connecticut writers, and mentioned them, major or minor league, casual acquaintances or close friends, as if they were all worthy of Nobel Prizes.

“After all, the Prize Committee makes some dynamite choices,” he said, cracking one of his many trademark puns.

At the Hamden event, I had bought The Last Undiscovered Place, and for the first time, I found a “local author” whose book I was astounded by. It was Walden, but “inside out,” about community, culture, nature, and public life combined. The reader could see one small place through a multi-lensed panopticon, from every angle, making the book impossible to classify, mixing reportage, memoir, history, and a dozen other disciplines.

“How many drafts?” I asked, thinking that no one could possibly write more versions than I did.

“Eight or nine.” His beard cracked with a smile. “I read it out loud to catch the repetitions, you know, the things you don’t catch with your eyes.”

Well, I thought, this guy is serious about his work. Soon I found out how serious, learning about his regimented, precise method, with time parceled out into the days and weeks. His research always included multiple interviews, visits to every site he talked about, and notecards for every reference. I couldn’t decide whether I was intimidated or inspired.

“I’ve always worked here, in isolation,” he said when I asked him about his process. “I can edit or do other work at the coffee shop. But the first draft, the bloodletting, takes place right in my office.”

When I visited his home, I found out why. David lived in an 1847 Greek Revival house on the Collinsville Green, writing every day in a former drawing room with views of a sugar maple and the white clapboard Congregational Church. It was a luminous space, surrounded by books and artifacts collected from a lifetime of hiking and canoeing. The daily journal he had kept since May 29, 1978, stacked impressively along one wall. He sat rigidly at a three-board pine table in a flannel shirt and jeans, glasses squared on his nose, hair and beard shot through with silver, sipping a hot mug of coffee. Then the nerve in his neck would begin to pinch, and he would stand up and walk around, wincing with the pain, but somehow cracking a joke instead of a curse.

Along with his daily struggle with pain, I found out that he wrote The Last Undiscovered Place while grappling with divorce and single fatherhood, sometimes waking up at 2:30 a.m. to find time to write. It took him six years to write this first complete book, and in my opinion the result had been well worth it, the best “local history” –if that label could even be applied– that I have ever read. It was a home run, even if a small crowd watched it sail over the wall.

By time I met David he had been forced into retirement by the nerve damage, but he had worked as a handyman, janitor, and pot washer to put himself through the University of Massachusetts before becoming a lawyer and finding work in the Connecticut General Assembly. “Some of us were in the vault in the cellar of the State Capitol with one hanging light bulb,” he said. “No kidding. But I loved it.” Then he became the Deputy Commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, writing most of our first “green plan” and saving hectares of open space when he negotiated the largest land conservation deal in the history of the state. In retirement, he continued to work for the public as best he could, serving as the historian for the town of Canton, acting as moderator for town meetings, and continuing to serve in an administrative capacity for the local fire department.

“I think volunteerism is at the very axis of what it is to be an American from the Minutemen at Concord and Lexington to the guy who coaches Little League,” he told me, without a hint of shoulder-shrugging irony.

“Well,” I said. “Writing is kind of like volunteer work.”

“You have to write for the love of it,” he agreed. “Because it is certainly not for the money.”

I don’t know if I was more ambitious than David, but I always believed that someday that would change. I was excited by the attention my books were getting and thought that this would inevitably lead to more money and fame. In those years, every radio program I spoke on, every local access cable television show that hosted me, every newspaper article mentioning my appearances or work…I loved it all. When a network television affiliate showcased me, or when a regional magazine ran a feature story, I admit I felt a thrill. Weren’t these the fruits of authorhood? A photographer traveling to our house to take shots for the front page of a newspaper, a reporter meeting me in a bookstore for an interview, a television personality giving us an hour of time, a mayor shaking my hand for a publicity photo. It was all happening.

One of those early books was Becoming Tom Thumb, the first thorough biography of diminutive 19th century performer Charles Stratton. Shortly after it was released, an English producer contacted me and told me that he and his production company had read it and were using it to plan a documentary on Charles and his manager P.T. Barnum. Would I like to participate? You bet I would. So, I met the producer when he came scouting the locations, and a few months later on a cold winter day, they returned to film in Bridgeport and several other American towns. The host of the documentary was the former chair of the BBC, Michael Grade, a man who had done nearly everything in British television. He had recently been made a life peer and sat in the House of Lords, though I didn’t know that until later. He had jumped at the chance to host this because his own family came from “circus people.” The director set up in the wood-paneled parlor of one of the old houses owned by the university, and Michael…Lord Grade…interviewed me for three hours, while Amy watched proudly from a chair nearby.

The following day, I drove to Middleborough, Massachusetts to the house Charles Stratton and his wife, Lavinia Warren, had shared in the 1870s. No film crew had peeked inside for decades, and I was excited to see the house itself, beyond the fact that I would be appearing in a film-length BBC documentary. I waited in my car nearby as snowflakes began to swirl. About an hour later the film crew showed up, just as the snow began to really fall. As a precaution, I booked a room at a nearby hotel, and later the crew joined me there – no one was getting out of town that night. But we had a documentary to film! So, even as the snow began piling up on our cars and the front lawn, we started filming. I did some unscripted exterior shots with Michael and then, as so often happens in the “industry,” I waited for an hour while they did more scripted exterior work. Finally, the director scoped the interior, and Michael and I talked to the family who owned the place at the time. The owner’s sister, who was a theater major, took us on a lively tour of the house. Of course, we did several takes for each bit. The director had made sure that as the “Tom Thumb expert,” I had not seen any of the wonderful details before so that my “surprise” and enthusiasm would show up on tape. Built into the house was the miniature stove, miniature tub, and a staircase built at a sort of compromise height for the Strattons and their servants. The family had also found a pair of Lavinia’s shoes in the back of a cabinet and had re-purchased a Tom Thumb miniature piano and a pair of lawn bowling balls given to him by an Australian club. I reacted appropriately to each revelation, and then off camera, I spent a moment in the room Charles died in. I talked a little to his ghost, then, telling him that I hoped my book had done him justice.

Filming had taken a long time, and a foot of snow had gathered along the country lanes. We drove through the darkening evening to the hotel, taking a half hour to go four miles. But since the hotel had no restaurant, we had to venture out again, slipping and sliding another three miles to a nearly empty bistro. It was not a palace, but we were hungry, and sat down to a hearty dinner as snow drifted and piled outside. Michael regaled us with stories, at one point telling us that in the 1970s, a friend had called him to consult about a bad situation facing his client, who had agreed to act in a film with a largely unknown American director. The production had run out of money and the director offered a percentage of the take rather than a flat fee. “I told him it was a bad idea,” Michael said. “But the actor stuck with it, because he liked the script.”

As Michael slyly revealed, the actor was Alec Guinness, the movie was Star Wars, and he made a mint. The first check alone was five million pounds, an amount equal to the rest of all the money held by his small bank in Sussex.

“I was always glad Alec didn’t take my advice on that occasion…,” Michael finished dryly.

The crew was already gone when I woke up the next morning, on their way to New York to film more scenes. Driving home across the long leagues of Interstate 90, blustery wind sweeping snow around my car, I thought for sure I had made it to the major leagues. At the very least, I told myself, I could parlay this into a deal with a larger publisher. But despite several awards, the book never sold out its first printing, and my subsequent proposals to major presses were rejected. That early excitement would return –briefly– every time I was consulted in the years following by major league venues like the Atlantic Monthly, the Wall Street Journal, or the History Channel. The next one was the one that would send me up to the show. I just knew it.

Unlike me, David often seemed to revel in being a minor league author. It’s not that he didn’t want to sell copies – he worked constantly at that, giving dozens of presentations and readings every year. But he had no real interest in fame, probably because he had already seen the dark side of it. Shortly before I met him, a certain state agency found David Leff practicing law, and sued him for his disability retirement money. It was the wrong David Leff, actually a lawyer of the same name in New Haven. Apparently unwilling to admit the mistake, they sued him anyway, charging that his writing constituted work and that his nerve damage was faked. His own book, Deep Travel, was used against him in the hearings, as they tried to demonstrate that his brief canoe trips on the Concord River meant he wasn’t really injured. He came out of his house one morning to find the workmen he had hired to restore it sitting on the front step reading an article about the ongoing lawsuit on the front page of the newspaper. It was humiliating, to say the least. He received hate mail and threats, becoming “a poster child for the excesses of the system,” as he put it. Worse, he didn’t have the money to fight the deep pockets of the state and had to sign a compromise document. Years later, when his primary tormentor retired, representatives of the state agency that plagued him apologized privately. But no newspaper covered that.

He did not let the bad experience with the media and the state make him bitter or turn him into a misanthrope. “Make the most of where you are most of the time,” he said. “There’s so much joy in life.” When you met David, it was obvious he lived that maxim fully. I didn’t trust the world as much as he did, but I did trust him. Someone who has seen both sides of fame was someone I needed to hear from, to balance out the ambitions of my own grasping soul.

Authors, even minor league authors, have a weird sort of celebrity. Most of it is second-hand, through the work of art, through words. The exception, of course, is during author readings and presentations, which had been part of the lifestyle I had witnessed and envied. And at first, despite performance anxiety, it was fun. Amy and I gave an average of thirty presentations or readings a year, some unpaid, some paid, some to five people, some to a hundred. We gave presentations at libraries, bookstores, schools, museums, casinos, town halls, town greens, senior centers, and conference centers. We gave presentations to business groups and women’s groups, to historical societies and secret societies.

Amy often recited her poetry, and I gave occasional readings of fiction or creative nonfiction, but most of the events were presentations for history books, either those I wrote myself or ones we wrote together. We gave over a hundred presentations just on the history of Connecticut food. We would arrive early, shake hands with the organizer, and set up the projector and laptop. Our books were stacked on a small table with printed sheets denoting prices and special sales. We would test the podium and crackling microphone, perhaps framed by an emergency exit, and greet the guests one by one as they arrived, making small talk and trying to charm them into buying our work. Once, we drove an hour through driving snow to lecture five people, one of whom fell asleep and snored.

In general, bookstores were supportive of minor league authors and their struggles to get on the shelf. But a few were not. At a store on the gold coast of Fairfield County, the owner sitting at the front desk openly insulted us when we offered our “sell sheets” from regional publisher Homebound Publications. “We don’t carry self-published authors.” I tried to explain that it was a real press, but she wouldn’t listen, despite the fact that the store carried two of my history books, and I had just signed them. “We have a certain clientele here,” she said. Rich people? Families? I wasn’t sure, but I got the message. This was not a place for minor leaguers like us. Of course, turning away local authors is probably not the best business strategy. Who buys more books than writers?

Bookstores sometimes invited you for signings that were unaccompanied by readings or presentations. These were usually not productive events, and many times I spent two hours chatting with curious patrons to sell one or two books. Often, these events were not advertised on social media or local papers the way presentations were. In most big chain stores, there is little connection to the community, and little concern about the store or the local culture on the part of the workers. Perhaps that is why they kept dying during those years, one bookstore failing after another. That also happened to quite a few “local” shops who didn’t carry local authors or make their inventory unique and specific to the place. Bookstores always worked best as linchpins for a particular neighborhood, town, or region.

At one disheartening session I signed zero books, sitting helplessly behind a table at the entrance to the chain store while guests ignored me, or worse, talked to me. One woman asked me for a chiropractor recommendation, as if I was a search engine. “I had a dream about the Beast,” one man told me, as if I was a confessor. A family stopped by, looked at my pile of books, and realized they had made a mistake. “Have a good day, buddy. Hope you sell a lot,” the father said. An old, old man sat down nearby, talking loudly on his phone, and to me. “I’m 96 years old,” he said, and then, loudly enough for everyone to hear, told me a disgusting joke. Shortly afterwards a woman trapped me at the table to tell me about underground cities built by the trillionaires who were tapping our phones. She was also terribly angry that her husband who fought in World War II was not mentioned in a recent book.

I nodded. “That can be frustrating.”

Afterwards, Amy quoted Bull Durham, as she often did in these situations: “Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose, sometimes it rains.”

However, after a few years of being published writers with minor league reputations, we began to get a few actual fans. “I have all your books,” one woman said to us while we were signing after a presentation, pointing to the dozen on the table. “Except this one.” She promptly bought it. “I know who you are,” one librarian told me, blushing, when I introduced myself. “Your work is lovely,” another told Amy. One dark winter day, feeling drained by my classes, I pressed the answering machine button in my Bridgeport office and a phone message from an anonymous woman told me that she had finished Becoming Tom Thumb and that it was the best book she ever read. That was enough to keep me going for a little while.

We were literary encounters for these folks, and that was a strange thought. We also began to meet more and more writers simply through the virtue of being authors ourselves. Once, walking across the vaulted neon hall at Mohegan Sun during the Big Book Club Getaway, Amy and I spotted a black-haired woman with a copy of A History of Connecticut Food.

“Would you like us to sign that?” we asked, having just signed several after a panel discussion.

She let us do it, and as we asked her name, she seemed surprised that we didn’t know it. “Debbie,” she said, smiling broadly.

“Are you an author, too?” we asked.

“Oh, I’ve written a few,” she said, laughing a little and heading to the cashier to pay for her armload of books. We looked at the main author table for a “Debbie.” Turned out that she was the headliner for the event, a number-one New York Times bestselling author with over 200 million copies of her books in print. Embarrassed, we slunk across the thick carpets toward the cling-clang of slot machines to try our luck there instead.

These frequent but brief encounters often ended ambiguously, and sometimes the most we could hope for was not to annoy the major league author. I succeeded with one best-selling novelist and did not with two well-known historians. Amy was somewhat more successful, and usually charmed the poets she read alongside. After a presentation in Stratford, we ate lunch with Robert Frost’s granddaughter, elderly but lucid and sharp; she bought one of Amy’s poetry collections.

“Ernest Hemingway used to think of other writers as competitors,” I mentioned to David once, as we walked along the Farmington River in Collinsville. “He sized up everyone he met, dead or alive, and tried to outbox them.”

“Really?” David seemed surprised. “To motivate himself?”

“Yes. But Amy thinks that this is a crazy attitude.”

“She is a wise woman. You would do well to stick with her.”

“That’s the plan,” I said. “That’s the plan.”

“Do you think that way?” He pointed to a large oak. “I mean, would you want to wrestle Ernest Hemingway?”

“I used to.” I followed the line of his arm to see a red-tailed hawk perched on a branch. “But not anymore.”

Minor league careers can live or die by book reviews, and I was shocked to find that reviewers and critics did always not read your work. If they had a grudge to settle or an ego trip that had nothing to do with you, you could sometimes dismiss it. “You’ve hit the big time now,” Jim Lampos told me when I asked what to do about a supposedly professional reviewer who slammed my book without reading beyond the introduction. “That’s the price of fame.” However, in this internet age even anonymous individuals could give you bad reviews, though often it was quite clear who they were, and even clearer that the book was not their real target. Bad reviews only really hurt if they were accurate, which seemed almost never. Instead, they annoyed you and awoke a sense of injustice, which was nearly as bad. You always had to be careful not to become a righteous victim. What you wished for as an author was a fair review, good or bad. Maybe the book was actually awful.

Another problem arose from the opposite situation – occasionally people liked your work so much that they passed it off as their own. An article by a major critic for the New York Times materialized two months after one of our books, detailing the exact argument Amy and I had made, but without any reference to our work. A popular television show on a major network did the same. Our friend, Chef Bun Lai, told us this was absurdly common in the food industry. “I’ve seen my recipes on a dozen New York restaurant menus,” he said with a good-natured laugh. “You just have to let it go.”

One year Amy and I found out that one of our history books had been pirated by an unknown company that used artificial intelligence to rework certain areas and republish it under various fake names and fake titles. When I asked around, I found out that others had also suffered this fate. Minor league authors were apparently the easiest to steal from. One friend had his magazine articles republished under someone else’s name willy-nilly on the internet. Worse, there was almost no legal recourse against this piracy of our words and ideas. Was this the future of authorhood? As anonymous content providers? Or would robots put us out of our jobs entirely?

Major leaguers have all these struggles to deal with, and more. But at least for them there is actual money at stake. Celebrity may suck, but it pays the bills. Or so I thought in those days, anyway. What good was my picture on the front page of Connecticut newspapers if only a couple dozen people bought my books each time? Why was I adding to my trouble for the little bit of pleasure and cash it gave?

Hate mail occasionally arrived, and I always respected if not liked those who at least signed their names. But other messages were unsigned, anonymous, cowardly. One postcard even arrived with typed paper pasted to it, like a ransom note. We weren’t popular enough to get death threats, I guess, so that was a plus. However, we knew plenty of others who did. Once, we were enjoying a nice Italian dinner with a major league author and scholar who we had invited to speak at the university. She appeared on cable television and talk radio frequently and spoke on divisive political topics.

“You must get a lot of hate mail,” I said.

“Oh yes,” she said after finishing a bite. “A lot of racist stuff, in particular, and other terrible threats. I try not to look at it.”

“I don’t know how you deal with it,” I said. “I get very anxious with far less hate than you probably get.”

“Oh, I think the anxiety of being in the public eye is unavoidable,” she said. “I try to focus on the final good, the cause.”

I thought about this. What was my cause? Literature? History? What was I doing that was so important? Did I have a purpose? I thought that perhaps it would become clearer as I sold more books, got more media attention, and found my audience. Likewise, as my minor league fame grew, I thought that the author events would gradually get bigger, with more and more fans showing up and more books being sold. That was not the case. One summer Amy and I stood on the stage at the Mohegan Sun Cabaret, presenting to a crowd of a hundred, complete with popstar headset microphones, a mixing board, and giant video screen. A month later we gave a presentation in the cramped cellar of a tiny library to four people, two of whom were my parents.

You could always count on an old man sleeping in a corner, a student taking notes for extra credit, a couple who thanks you profusely but does not buy a book. It could be demoralizing if you weren’t careful. There are days when you just want to give up, stop trying, sit back with a martini and let oblivion come. Seven years into our book tours, we gave what would be our last presentation on Literary Connecticut. We talked about the significance of stories, the connection of writing to place, and finally, the importance of supporting our own local writers. The twenty people attending seemed to love the lecture, asking numerous questions and applauding at the end. But no one supported the writers in front of them by buying a book. In a sandwich shop afterwards, eating a desultory lunch, we listened to Frank Sinatra’s voice filter through the sound system: “Here’s to the losers, bless ‘em all.”

That evening we drove to Collinsville and were greeted by David’s wide smile splitting his salty beard. Standing in his small, comfortable kitchen, I immediately began to complain about the fact that no one bought the books.

“That’s why I charge them up front.” He popped open a bottle of beer. “I may lose some opportunities that way, but our time is valuable. You are giving them knowledge. Did you get paid by the library?”

“Yes, a little.” I thought about it. “And I guess there was an article in the newspaper about it, so word about the book got out to people, even if those people didn’t come.”

“Well, there you go.”

“I know, but it is still depressing. Every time we fail like this…”

“Is it you that is failing?”

“It makes me feel like a hack.”

“Focus on the craft,” he told me. “The rewards will come, or they won’t. It is the work itself that matters.”

David’s wife Mary returned home from her work at the library, and the four of us shared a wonderful dinner, glasses of wine, and a vibrant conversation. That made for a good day, and Amy and I decided that, rather than freighting each presentation with expectation and ambition, we would simply make each an opportunity for exploration and for meeting friends. We might try a just-opened Korean restaurant or order fried oysters at an old favorite. We might buy tickets for a museum or a play, or we might call around to find friends who could meet us for drinks. Once, we arranged a reading to coincide with our publisher’s 34th birthday party.

Another way to cope was to have a few loyal fans. The antidote to fifty enemies is one friend, as Aristotle says. One librarian invited us for presentations at multiple libraries as her career bounced her around the state. A local pharmacy owner kept our books on a shelf for years, adding each new one as it came out, the only books in the store. One fan drove an hour to see us a second time, another followed us from venue to venue for different presentations and readings. These were the fans that made the work worth it, and gratitude fills my heart every time I think of them. For a minor league author, every loyal fan is important, in a way that they can never be for an international bestseller. We tried to spend time with each person who bought a book, to value their time in return for the value they placed on our words.

And of course, many of those fans were our fellow authors. One day near the end of the pandemic, we sat in David’s garden, red poppies and water iris in bloom, drinking together, eating from the same plates. It was a hot day but comfortable there in the shade of the trees with a north wind blowing. I asked about the strange green fire hydrant in his front yard, and he told us an intricate story about its origins and endurance. He talked about the long journey the water made from the reservoir and about winter days shoveling out the hydrant in case of possible fires. He talked about how unique it was, its long years of service, and its unheralded importance in the life of the small town.

Eventually the talk turned to literature, as it always did, and I mentioned that few had bought or reviewed my latest novel.

“The writing goes on. It matters to the writers and the people who read it,” said David. “I’m happy being a minor league author.”

He was right, as usual. Everything I had gained – the small shelf of books, the friends I had made – these were privileges, and I felt lucky to have any of it at all. Success is a privilege, and so is quitting. Who cared about joining the major leagues? After a couple years of isolation and video events, I just wanted to visit a library again, to sell a few hundred or a few thousand books, to sit across from my friends at a local brewery and discuss our latest projects. I no longer wanted to go to the show; I just wanted to keep playing for a few more seasons. Two-hundred-forty-seven home runs in the minor leagues might be a dubious honor. But it would be an honor nevertheless.

A few months later, Bethel’s tiny Byrd’s Books held one of its first post-pandemic live events, a Sunday poetry reading that included David and Amy, among many others. Amy was recovering from a bout of Covid, and David was suffering from terrible pain caused by his ever-present nerve injury, unable to stay in one position or sleep for more than thirty minutes at a time. His fifth spinal surgery was scheduled for that Friday.

From the podium in the little bookstore, owner Alice Hutchinson welcomed everyone and introduced each poet. Amy chose one poem from each of her six collections, her chestnut hair luminous in the afternoon light. David read from his forthcoming Homebound Publications collection, Blue Marble Gazetteer. His second poem included “salty” dialogue, and I worried for him and for all the poets and risk-takers of language in these times. And I worried about his surgery, though I tried to maintain a brave face whenever we locked eyes across the room.

After the reading, Mary, Amy, David, and I sat at outdoor tavern tables across the street from statues of Abraham Lincoln and P.T. Barnum, enjoying the cool spring air together. We sipped drinks and ordered food while David regaled us with tales of their recent adventures, including a funny story about a visit to the emergency room the previous Saturday night. When he disappeared into the restroom, Mary thanked us and told us that this was the most cheerful he had been in weeks. “He is in terrible pain.”

“Well, hopefully the surgery will work.”

When he returned, we talked about our plans for the future. “Thanks for your help with the chapters of the Great Mountain Forest book,” he told me, referring to his work-in-progress about this small area of Connecticut from ancient times to the present. “I made the changes you suggested.”

“It’s going to be good.”

He waved my compliment away. “I’m excited about the project. But now I’m getting into modern times, where the actual people I’m talking about, or their children, are still alive. It’s tough to know how to handle that.”

“You always want to be respectful of people.”

“But be honest.”

“I also have to be mindful of what I put my efforts into. If I choose this, I can’t do something else. It might take me two more years.” He shifted in his seat uncomfortably and stood up to lessen the pain. “But if I become the state poet laureate, then this will go on the back burner, and I will put my efforts into that.” He laughed. “That’s a big if.”

“I think you really have a good chance at that,” Amy told him.

“If not at the Nobel Prize,” I joked.

“Well, I’m not that interested in accolades, but you never know,” he chuckled. “They make some dynamite choices.”

Two weeks later at his memorial service on the Collinsville Green, hundreds of people gathered on the lawns of the 19th century houses and milled about the closed-off street: uniformed volunteer firefighters and black-clad beat poets, environmentalists and politicians, rabbis and librarians. I sat on the corner of his lawn by the fire hydrant with Amy and a few other minor league authors. Everyone faced a podium set up in front of a huge red fire truck and the white peak of the Congregational Church. The murmur of the crowd blended with the distant melody of the Farmington River, rushing through the valley below.

Swallows caught insects above the chimneys and a cat meowed somewhere in the gardens on the hill. Bright green trees and white puffy clouds seemed to refute the somber occasion as David’s family emerged from the house and a rabbi began the ceremony. Two Connecticut poet laureates stood up to read his work, and I realized that he would never reach that position now, his application sitting fallow in some bare office room. Speaker after speaker read eulogies, with descriptions like “Man of Letters” and “Renaissance Man” echoing again and again. Indeed, the echo of the man himself was in every word and in every face. I felt like I could turn around and see him puttering around in his beloved garden, but when I did glance over the fence, I saw only flowers.

The sun began to set through the maple trees, the hot day cooled, and the seemingly inevitable rain held off. Mary stood up to read a poem, somehow managing to repeat her husband’s pun about visiting ancient cemeteries during the pandemic lockdown, “where everyone was safely six feet distanced.” The bells of the Congregational Church pealed, and we walked away from the Green, heading to a tavern for a late dinner, to a night of conversation and laughter that resembled David’s own rough vision of paradise.

Well, Eric, I could hear him saying, it is the work itself that matters. Literature goes on, and our little streams flow into it. What is literature after all, but the work of thousands of ordinary writers reaching for extraordinary words? We are all minor league authors – I was going to say, “even the best of us.” But perhaps I should say, especially the best of us. Not because there is quality hidden in the bullrushes, but because literature –true literature, good literature– springs from hope.

BIO

Eric D. Lehman is the author of 22 books of fiction, travel, and history, including 9 Lupine Road, New England Nature, Homegrown Terror: Benedict Arnold and the Burning of New London, and Becoming Tom Thumb: Charles Stratton, P.T. Barnum, and the Dawn of American Celebrity, which won the Henry Russell Hitchcock Award from the Victorian Society of America and was chosen as one of the American Library Association’s outstanding university press books of the year. His novel 9 Lupine Road was a finalist for the Connecticut Book Award, and my novella, Shadows of Paris, was a finalist for the Connecticut Book Award, a silver medalist in the Foreword Review’s Independent Book Awards, and won the novella of the year from the Next Generation Indie Book Awards.