The Writing Disorder Interview

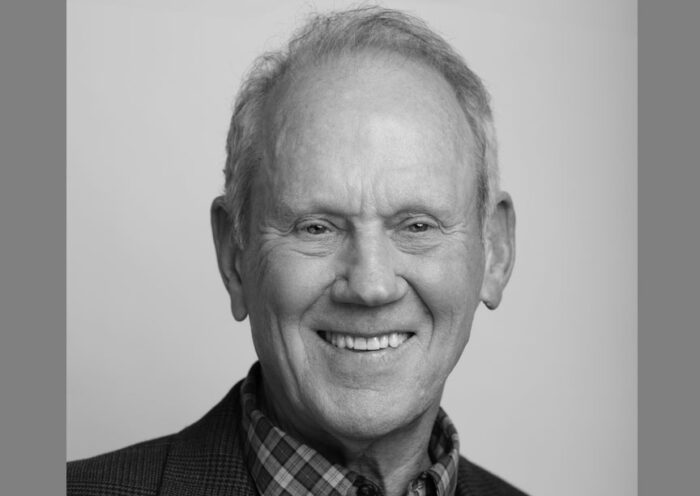

Deborah Holt Larkin

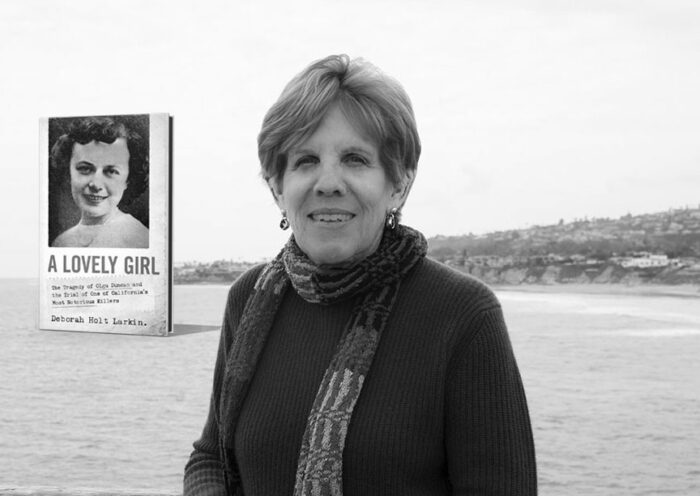

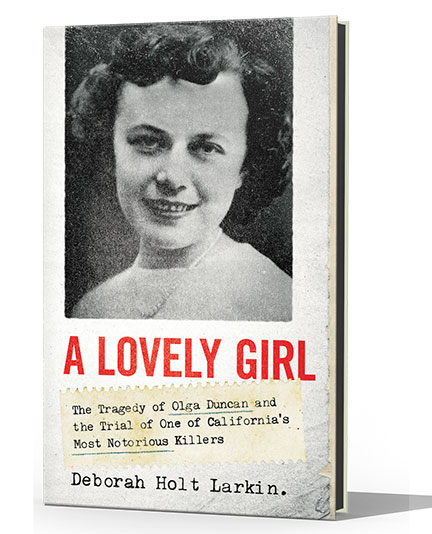

Deborah Holt Larkin grew up in the small coastal town of Ventura, CA. In the 1950s, her father, Bob Holt, was a newspaper journalist and columnist for the Ventura County Star-Free Press. Beginning in 1958, her father covered one of the most famous criminal cases in Ventura County history. When Deborah was only a child, her father attended the trial on a daily basis, following it through from opening statements to the verdict and punishment phases. As her father came home at night, Deborah would ask him for details about the case and the courtroom proceedings. Deborah recently wrote an exceptional and detailed account of the famous case of Elizabeth Duncan (A Lovely Girl, 2022), the woman who was convicted of murdering the pregnant wife of her son, Frank Duncan. Elizabeth Duncan was the last woman put to death by the state of California. Like the case itself, the memories of this period in her young, impressionable life haunted Deborah throughout her life—until it finally came out in book form.

*

I met Deborah recently at a local book festival in Carpinteria, just north of Ventura. As we sat down to talk, a train, the Surfliner, was passing by.

The Writing Disorder: Have you been to Carpinteria lately?

Deborah Holt Larkin: I haven’t been here since I was a little girl. A friend’s grandmother used to live here. We’d come up here and stay with her family. We would sometimes camp out in her backyard, and we would hear the trains pass by at night. My family lived on Alameda Avenue in Montalvo, and our house was right near the railroad tracks. So, we heard the trains going by all the time.

TWD: What about Ventura?

DHL: A local historian, Glenda Jackson, used to give tours of the Ventura courthouse (built in 1926). She would take groups up to the old court room and tell them all about the infamous trial of Elizabeth Duncan. It’s a beautiful old building. I actually spoke there last year about my book. My sister still lives in Ventura — in the same house where we grew up.

TWD: My friend, Susan, who grew up in Ventura and worked at the courthouse, said they used to display a large photo of Elizabeth (aka Ma) Duncan up in the window upstairs. So, when you looked up from the street below you would see her face in the window.

DHL: When I was in college, I got a summer job as a student intern at Camarillo State Hospital. I got it through my mother who worked there as a psychiatric social worker. I was an intern in the school there and I remember that they seemed to treat children with mental illness as if it were some kind of parenting error. And I remember sitting out front on the lawn and watching the parents who would come visit. It wasn’t because of bad parenting. My mother was a big influence on me too, as far as some of her experiences working there at the hospital. I put this in the book, and I remember my mother saying, “I just hope I live long enough for there to be a cure for mental illness.”

TWD: The things your parents exposed you to as a child were quite provocative.

DHL: It was a different family. It was very unusual at the time for my mother to be working. She was the only married mom I knew who held a job. For the most part, women didn’t work when they were married.

TWD: And there weren’t a lot of divorced parents back then either.

DHL: No. There were some that had lost their husbands during the war.

TWD: How did the book come about? Was it through your writing class?

DHL: First of all, the story of the trial shadowed me my whole life. And I wanted to be a writer. It was something I always had a dream of becoming. When I first went away to college, I didn’t have the confidence. Even though my teachers always commented on how good my writing was. I would get comments on my papers like, very well written. So, I went into education. When I graduated from college in the 1970s, a lot of women were going into education. That was something we all did. And then thirty years later I started taking writing classes at UC San Diego, because I wanted to be able to do it right. I wanted to write a fictionalized account of the Duncan case. That was my goal. I was going to write a novel and fictionalize the story.

TWD: You know your book feels like fiction. It reads like a story.

DHL: I’ll tell you a little more about that. But I started to fictionalize the story. But the more chapters I wrote—I would just end up tearing them up, because the case is stranger than fiction. It doesn’t sound believable. And for fiction, it does need to have a certain quality. Even if it really happened, it might be hard to believe as fiction. And people in my writing class used to say that, that it wasn’t believable. Even after I started writing the book as nonfiction, people would still say it to me that it was unbelievable. And I would say, I’m sorry, but that’s what actually happened. It’s actually right there in the trial transcripts.

So as soon as my youngest son went off to college, I started taking writing classes. That’s when I first had the idea to write it as a novel. And then I got into a writer’s group, with reading critiques. It was at that point that I realized fictionalizing the case wasn’t going to work. So, I would bring in ten pages every week to the group and the other writers in the group would comment and critique my pages. I didn’t actually have a book I was working on at the time. Sometimes I would bring in personal essays, and it would be about my family and about my dad. And other times I would bring in something that was more like a police procedural, writing about this true murder case. One night I brought in something about my dad and the murder, and his reporting about the trial. Mark, the teacher/leader of the group, said, you know, Deborah, I think you have a book here. He suggested I write both my memoir about my dad and family, and about investigation and trial, and also some of the actual court proceedings, and weave it all together as one book. I thought about it, and I decided that it was a really great idea. So that was Mark’s idea. I gave him credit at the end of the book.

TWD: The structure works really well. You get really involved with the case, but you also welcome the relief with your own personal story about family and life growing up.

DHL: And then a very fortunate thing happened. After I had written most of the book, I had met with an agent who was interested in it. I sent her the whole manuscript, and when she finally got back to me, she said she really loved it, but she thought there was a problem with the pace of the book. She thought the family chapters were slowing down the pace. She wanted me to work on it and then she would take another look. So, I did. And I realized that as the trial approaches, there needed to be more true crime chapters and less personal chapters about my family to rev up the tension of the crime story.

I wrote it as literary nonfiction. And in literary nonfiction, all the facts are true, but you can write scenes where they’re drinking a cup of coffee, or you can describe the weather, or how someone might sit or walk down the street. I actually looked up the weather at the time. But there are little details like brushing your hand through your hair or sitting in a chair. So, all that is part of literary nonfiction.And I wanted to write it like I was telling a story.

When I started the book, I got 5,000 pages of the trial transcripts from the courts. When I was reading that, it felt like I was there in the courtroom. When the people testified, they were very candid. And they tell what they did. And the fact that the two men had already confessed to the crime. I had Newspaper articles from four newspapers, my father’s files and all that testimony. I had the grand jury testimony of all the witnesses. I just couldn’t put all that in the book. So, what I did was to create scenes. When you’re reading the interview of the landlady by the detective, those words are exactly said told the grand jury. When I read those transcripts, I felt like I was really there. It all turned black and white in my mind. I felt that I was there in that public gallery when everyone was gasping at the outrageous testimony of the killers. So, I wanted readers to be able to experience it that way. There’s much more of an intimacy when you’re writing in the literary nonfiction style than a journalistic style. So that’s how I wrote it.

There aren’t any things about the case in the book that aren’t true. I can tell you where every fact came from, either the trial transcripts, or multiple newspapers interviews or my father’s files. I also was able to read the unpublished memoir of the DA who prosecuted the case. I got a lot of insight into his thinking and could be in his head in the court scenes.

TWD: Tell me more about that.

I was staying with this couple in Ojai, and she was getting married about halfway through writing the book. And she said one of her high school friends, Bob, was coming to the wedding and he had a lot of information about the Duncan case. He’s the one that found the transcripts that were said to be lost. That story is in the back of the book. So, when I met him, we talked about the case. I told him about my book. And he said he would send me the trial transcripts. I was missing of the original transcript, like Frank Duncan’s testimony, which was pretty important. And he said he had something else I might be interested in. He said, “I have Roy Gustafson’s (the prosecutor in the case) unpublished memoir.” Bob had worked in the same law firm that Roy worked in after he left the District Attorney’s office. Roy had already passed away when Bob started working there. So, in the early 2000s, the law firm was going out of business, and Bob was in the law library cleaning it out and up on the top shelf he discovered the lost transcripts of the Duncan case, and this unpublished memoir. The D.A.’s office wouldn’t have even had the transcripts at the time I came looking for them. So, Bob gave the transcripts back to the city, but he held onto to the memoir. And Roy didn’t have any children. So, he just left it there in the law firm.

I got the story from one of the lawyers that was still there at the time, and he said that Roy brought the transcripts over to the law office because he wanted to write the memoir. After he wrote it, he contacted one publisher and the publisher said no. It wasn’t written very well; it was more of a matter-of-fact style. But what I did get out of it when I read it were his thoughts on the proceedings, when he was prosecuting the case. His worries and concerns. So, when he thinks he’s ruined his own case, and what happened in that little room — I read all that in his memoir. So, I had all that information.

TWD: Everything just fell into place for you.

DHL: Yes, it did. And there were other things he wrote in his memoir. He gave his opinion on some of the witnesses, and their backgrounds. There were a couple of witnesses who were very credible. And those were his opinions. So, I got opinions of good and bad witnesses and why.

TWD: How did you get your book published?

DHL: While I was writing the book, I was hearing that publishers didn’t like books with mixed genres, and this was a dual genre book of memoir and true crime. And that publishers don’t necessarily like older authors. They like authors that write multiple books or series because the audience grows. And I had no platform, especially for a memoir. But I thought that this was what I wanted to write and I just kept writing and did the best I could. And in the end, it didn’t really matter. They say if you write a good enough book, none of the other stuff will matter. That’s what I was hoping for.

I had been working on it for nine years. And my youngest son said, mom you’re going to have to stop writing this. And I think I had eleven or twelve drafts. I. wanted to get it right. And I thought I could tell a good book; I read and write so much. I read true crime and everything else. So, I thought I could do this, since I read those kinds of book and I would know when it was right.

My son told me about the Santa Barbara Writers Conference. This was in 2019. He suggested I take it up there, since it was a Santa Barbara and Ventura County case. At this conference they have something called Advanced Readings. For an extra $50, you can pay to have an agent there read ten pages of your book. And they’ll come back to you with some feedback. I signed up for three agents. And I had done this before the book was even ready to be published, just to get some feedback. You can do it with editors or agents. So, I did that. And all I was expecting was to get a little more direction. And the agent I met with, we sat down and chatted. And she said she wanted to read the whole manuscript, that she loved it. And she’s only seen ten pages. She was the first agent I pitched. And she’s the one who suggested that I work on and improve the pace of the book. So, after that, it still took a while. We needed to make a book proposal. And she started pitching it to publishers. And she is a good agent. I looked her up and she has represented a lot of great books. She even represented one that was nominated for the National Book Award a few years ago. I could tell she would always send me the email that the editors would send her. And she knew these people personally. The first couple of rejections said that they didn’t know how to market the book. It’s true crime and it’s memoir. We don’t know how to market that type of book. So, we just kept going. It took about eight months. And towards the end — she was pitching this to good traditional publishers that I recognized — I told her to perhaps go with a lesser-known publisher. I don’t need a big advance and she said, oh no, you’re going to get an advance. We’re almost there. And sure enough, Pegasus Books offered me a contract a few weeks after we had that discussion. It didn’t take that long once I signed the publishing agreement. It only took about a year for the book to come out. It had already been well edited. They didn’t ask me to change hardly anything. The title, they chose that. My title was The Remarkable Duncan Case. That’s what my dad used to call it. That was my working title. I did have A Lovely Girl as one of my choices. But they added the subtitle. Everything went smoothly after that. The other thing that my agent said, is that publishers expect their authors to publicize the book. And they did have a publicist that they assigned me. But they still wanted me to do a lot of things to help promote the book. So my agent told them that I was a very experienced public speaker. And I thought, well, sure, at my school where I taught, and did training for teachers. I had been a school principal for a while. And then the book came out. And Pegasus Books was great. They set up a lot of speaking events for me at the beginning.

I’m going to be on a panel at the San Diego Book Festival. And I’ve done other book festivals in California.

TWD: Has there been any talk of turning this book into a movie or series?

DHL: I’ve already sold an option. My agent sold an option just before the Writers’ strike happened. And it’s a good company. They have a developmental production company. So, they want to develop it as a limited series on a streaming platform. They have something they did for Netflix. I’ve been told there are a lot of film options for authors and their books out there, but very few of them make it into production.

TWD: There are writers who make a living optioning the film rights to their books but are never made into anything.

DHL: It’s a two-year option. So, we’ll see what happens.

TWD: What are you working on now?

DHL: Not too much. I get overwhelmed by all the things that have happened since the book came out. It’s a lot of work. I would like to write some short stories. And I would also like to write a book for a younger audience, a mystery of some kind. I have a lot of experience with children, being a teacher. I have a good ear for children’s voices. So, I would like to write a young adult mystery of some kind. Based on my experiences as a child, children are interested in those kinds of things. Not necessarily the graphic, gruesome details, but they’re interested in learning about a lot of things. I’m not sure if they involve murder though. Maybe they have to be rescued.

TWD: You could be a character as a child. You can’t really go into the minds of your two main characters, the mother and son, but how do you read them. What is your take on their lives?

DHL: I tried to read them from their testimony. I think Elizabeth Duncan was probably what they call a malignant narcissist. One thing that I didn’t get into the book was when she plotted a jail escape, when she was in the county jail. It was so preposterous. I don’t think the woman ever thought one step ahead. She was in the moment, and she came up with all these plots, told lies, and moved on. I’m not even sure she even thought about what would happen to Olga, Frank’s wife. She just wanted to get rid of her, and she hired those guys to do it. I don’t think she ever thought it through. I think Frank Duncan was just trying to save his mother from the gas chamber. I think he knew, at some point, that she was guilty. A lot of people thought that he was in on the plot. But I don’t believe that was the case at all. It would have never been solved if he hadn’t dragged his mother down to the Santa Barbara Police Station to report this phony extortion case she’d made up to cover-up why she needed money to pay off the killers. Frank said something at the end, when he was testifying during the penalty phase of the trial. He said, when asked about his mother and about marrying all these different men, he said, “You know some people like to think about or dwell on their problems, but that’s not me.” He just didn’t want to think about it. What’s in the past is in the past.

The D.A., Roy Gustafson, talks about Frank Duncan in his memoir. He hated Frank Duncan. He despised him.

I remember I tried to get in touch with her son, Frank Duncan, and he hung up on me. He still had a law office in Los Angeles. He answered the phone. As soon as I started talking, he hung up. Bob, the man who found the trial transcripts, said he had seen Frank Duncan appear in his court room. He was representing an old client and was still practicing law. He said he was very cordial and polite, almost like a southern gentleman. He was in 80s at the time and seemed very sharp and knew the law. He was still practicing well into his 80s. His wife had passed away. I believe later that he lived in an assisted living facility. He had one child, a daughter. I think she still lives in Ventura County. But I decided not to contact her. I didn’t think it would be reliable information.

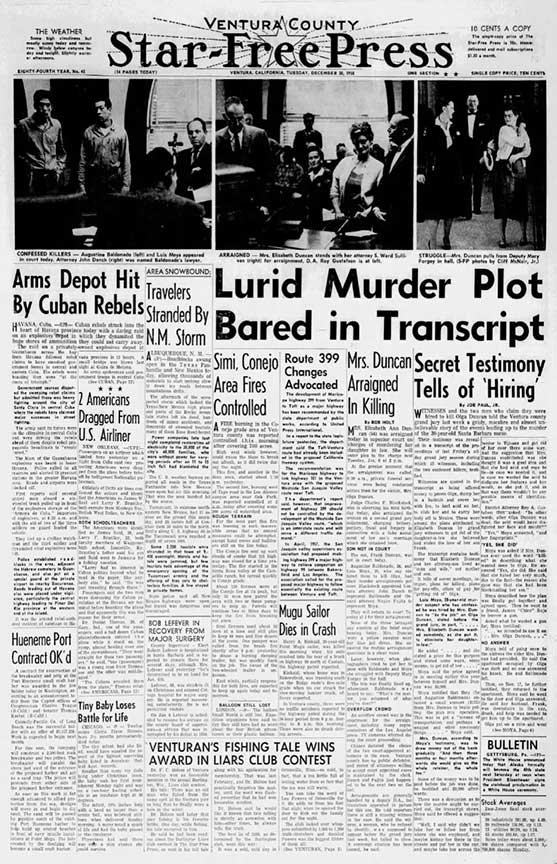

TWD: I found some old newspaper articles where they printed large sections of the transcripts from the trial right on the front page.

DHL: It was unusual that they would print the grand jury transcripts in the newspaper. Mrs. Duncan’s attorney complained about that. It was some like series from a true crime mystery. He felt it would poison the jury pool because everyone had read that.

There was a Lifetime movie made about the case several years ago. But they changed everyone’s name so they wouldn’t get sued by Frank Duncan.

You know how in the book I describe what everyone was wearing. I didn’t make that up. There was a Los Angeles newspaper, The Herald Examiner, they described everything about the witnesses—their clothes, their movements, and their emotions. It was all in the newspaper reports. They even covered—there was a lot of drama going on during the recesses at the court, and before the trial started. Mrs. Duncan would call people names during the recesses. It was all in the newspaper.

TWD: Some of the buildings—the school and churches—you visited as a child are still there in Ventura.

DHL: Yes, the elementary school I went to is still there, and some of the churches I went to with my friends. Judy and I liked to go to the vacation Bible schools.

TWD: Ventura has the oldest pier in the state of California, built in 1872. It’s being repaired now from recent storm damage. But it’s supposed to reopen this summer.

DHL: My parents have a bench on the pier. It’s just before the gates. So, whenever I go to Ventura, I like to sit on their bench. They liked to walk on the beach there. The newspaper offices where my dad worked are gone now. It must’ve been nice to work downtown. Ventura was such a small area at the time. Everything was walkable from his office. It was just a little town by the ocean.

TWD: Your dad was quite a character. He expressed himself freely.

DHL: Yes, he was very original. I don’t know where all that came from.

TWD: How did you end up in San Diego?

DHL: I went to graduate school there. That’s how I ended up living down there now.

TWD: From one beach community to another. I love all the history you put into the book about the city of Ventura.

DHL: I’ve been told that my book is a true crime book for readers who don’t usually read true crime books.

TWD: That’s true, because I usually don’t. Does anyone call you Deborah?

DHL: No, everyone calls me Debby. I just hope I live long enough to see the book made into a series. I get to be a Consultant Producer. Since this book is about me and my family, I was worried about how we would be portrayed. So, I told the producers that I would like to know their thoughts about my family. My agent thought Annette Bening would be good as Elizabeth Duncan. But we’ll see. No one ever wrote a definitive book about this notorious crime, until I wrote mine.

TWD: Thank you very much. It was great to meet you and talk about your amazing book.

DHL: Thank you.