THE SECRET AGENT

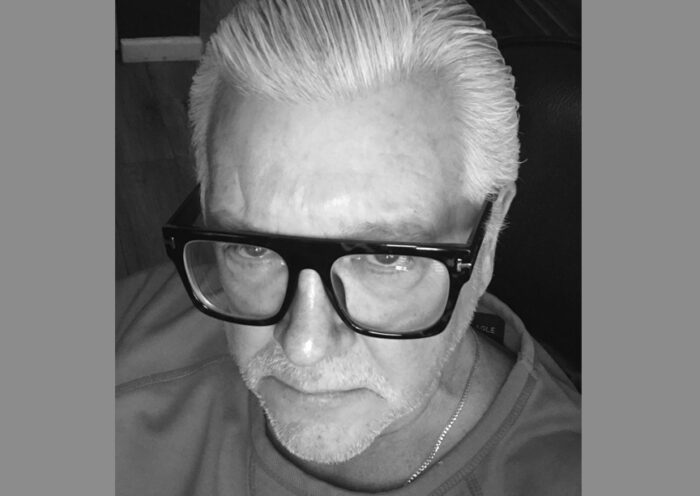

By Robert Collings

There is a celebrated short story called “The Rocking Horse Winner” by D. H. Lawrence. The story is so revered by scholars that you will find it on the required reading list for every English literature course in the English speaking world, and there are more translations than you can count. It tells the tale of a disturbed kid who enters a fantasy world and rides his rocking horse so he can pick the winner of real-life races and bring money into his dysfunctional household. The kid dies in the end after a particularly harrowing ride, and I could never figure out if he ended up picking another winner in that last ride, or whether the horses and the money didn’t really exist at all and were just symbols for something else. “All great literature has a speculative element,” my English professor would tell us. “Just like the boy in the story, that’s how you pick a winner.”

I’ve often wondered over the years about the speculative elements in our own lives. For all of our bluster and our yearning, I wonder if we’re all riding some rocking horse that’s taking us nowhere.

Years ago, my wife and I lived in a condominium complex that had a large underground parking lot. We had been assigned two stalls in the lot, and to reach the stalls from the entrance we had to drive down a long corridor to the very back of the building, and then take a hard left and go all the way to the corner where the two stalls were located. This parking lot spanned the entire base of the building, and it had a hundred identical concrete pillars arranged in long rows in order to organize the parking spaces and keep everything propped up. I have always had a vivid imagination, and I’m a fatalist by nature, and I’d often wondered what the devastation might look like if one of those pillars ever gave way and every unit in the complex came squashing down on my head. I had made the daily journey through this sprawling concrete bunker for a good three years without a scratch, and that was surely a good sign.

I was on my way to work one morning and I was still in the underground. Just after I made the turn to head down the long driveway towards the gate, I noticed a figure out of the corner of my eye behind one of the cement pillars to my right. It looked like someone was hiding behind the pillar, deliberately trying to remain unseen. I pretended not to notice, but after I had passed the pillar I looked in my rear view mirror and saw a young boy run from behind that pillar to the pillar on the opposite side of the driveway, and then hide again, as if he was being chased and was trying to stay hidden. I didn’t get a close look at his face, but by his stature and his cat-quick movements I guessed he was in his early teens. I had to stop my car until the big gate lifted up, and when I looked back in my rear view mirror I was unable to see anything. No one seemed to be hiding anywhere, and the parking lot was empty. I thought this was curious but I didn’t dwell upon it, and I had forgotten all about the shadowy figure by the time I got home that evening.

A few days passed without incident. Then, on another morning when I was backing out of my parking stall, I noticed the same ghostly apparition at the far end of the lot. I stopped the car and squeezed closer towards the window to get a better look. The mysterious shadow was much further away than it had been before, but it had to be the same kid. This time, he was ducking behind one pillar, hiding for a few seconds, then dashing to the next pillar, hiding there for a few seconds, then jumping over to the next pillar, hiding, and repeating the sequence until he reached the main driveway. He had moved out of sight, but when I rounded the turn at the far side and headed towards the exit gate, I saw him suddenly dash out from the pillar beside me and run behind the car to the other side of the driveway. He had been so close that he almost brushed against the bumper. In a flash, he reached the next pillar and ducked behind it, like some stealth fugitive on the run. When I stopped for the gate I was close enough to him to see the tips of his sneakers sticking out from behind the narrow end of the pillar.

I cracked open my door and twisted my head back and shouted out, “Hey there! Hey! You there! What the hell are you doing there?”

I saw him pull his feet back, but there was no other movement. My voice echoed through all the concrete, followed by eerie silence. The metal gate creaked open, and I headed out.

The building had not come crashing down on my head, but I still thought about the incident in the parking lot all day. Perhaps this shadow-kid was a homeless person in need of food and shelter. Or a harmless demented kid from some institution who got lost and didn’t know where he was. I worried that I had not said the right thing to him as he hid behind the pillar. He had to know that I had seen him, so he must have been waiting for my reaction. I kept going over the words that I had used, and comparing those words to the words that a more sensible, mature person might have used to fit the situation. I worried that I shouldn’t have used a crude word like “hell”, which made me sound like our gruff building manager. I was not a gruff person. And I had repeated the word “there”, which made me sound like a frightened person grasping for words, and I was not that, either. Perhaps I should have said, “Hello, can I help you?” Or, “Son, do you need a lift?” I was ashamed of myself for not using more appropriate language to draw the mysterious kid out into the open and prove to him that I was not intimidated by strange figures in concrete parking lots.

I drove back through the parking lot that night with the eyes of a hawk, but I saw nothing.

“Do you know there’s someone down in the underground, sneaking around like a thief?” I asked my wife when I got home.

“Oh yeah, I see him all the time,” she replied

This surprised me. “You see him all the time? Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I dunno, he seems harmless enough.”

“Harmless like a thief.”

My wife laughed. “You worry too much about everything. No wonder your mother called you a worrywart.”

“That’s because there’s lots to worry about,” I said, only half-joking. “Haven’t I told you this before?”

“I know teenage boys because I teach them,” she said. “They’re all a little whacko.”

This may have been the sort of simple explanation we all look for, but there was something about the mysterious shadow-kid that I found unsettling. I had been appointed to the condominium council the year before, and I’d been assigned the job of keeping an eye on the building to help keep things in order and see if anyone was violating the by-laws. My title was “Bylaw Officer” if anyone asked. I thought this was a good excuse to speak to Joe the building manager and bring up the general topic of shadowy stick-figures loitering in the underground at all hours of the day and night.

“It’s not all night,” Joe muttered. He was fixing something in the boiler room because the fixit guy hadn’t shown up, and he didn’t want to be bothered. “Just all day. His name is Gray. He thinks he’s a secret agent.”

I’m rarely at a loss for words, but this stopped me cold. “He’s what? What are you talking about?”

“His mother says he never sleeps. He reads all night, and by day he’s a secret agent. So far, he hasn’t stolen anything or killed anyone, as far as I know.”

“What, you talk to his mother?”

“I asked her about him, sure.”

“So what did she tell you?”

“She’s crazy, too. They live up in 308.”

“Besides telling you she was crazy, did she tell you anything about her son?”

Joe kept working. “She didn’t go so far as to call him a nut case, if that’s what you mean.”

“What does he do? Doesn’t he go to school?”

“Kids do whatever they want these days. He goes to school, he doesn’t go to school. Who the hell knows?”

I was losing patience with Joe’s indifference, but I stayed calm. “Joe, I just want to know what that kid is doing in the underground.”

Joe smiled, but kept working. “You just called me ‘Joe’ so you must be pissed about something.”

This was true, and I was irritated that Joe had read my thoughts. “For God’s sake, all I want to know – “

“You’re in charge of the bylaws, aren’t you?” Joe interrupted, still smiling. “He thinks he’s a secret agent. There’s trouble ahead if you don’t do something. We have a bylaw against loitering, so do your job. His mother didn’t call him a nut case, but I will. Gray Whipple. Ever notice how all these nut cases always have funny last names? Whipple, Gripple, Schmipple…it’s a strange world. ”

I thought about the strange world we live in. “There’s a bylaw against loitering,” I mused. “But I don’t know if it applies to someone who lives in the building.”

“Doesn’t matter,” Joe said. “One little spark can cause a fire that burns the building down. Then the whole city follows after that, and then who knows? You gotta nip these things in the bud.”

I couldn’t help following Joe’s reasoning to its logical conclusion, and I did not relish the thought of being the condominium bylaw officer responsible for putting an end to civilization as we know it.

Joe seemed pleased that I was not arguing with him. He nodded towards his toolbox and said politely, “My last name is Smith and I’m happy with it. Can you hand me that goddammed wrench?”

Unit 308 was directly above the boiler room. I’m not sure what compulsion drove me upstairs because no one had ever complained about the secret agent kid, and I certainly didn’t want to be accused of letting the power of my office go to my head. Still, my curiosity pulled me into the elevator and a few seconds later I was at the door of unit 308. Maybe Joe had a point. There might be big trouble ahead if I didn’t put an immediate stop to this nonsense, and I’d even been warned in advance by no less an authority than the building manager. I gave a few gentle knocks and listened for the sounds of movement inside. I heard very faint footsteps, followed by the click of a bolt lock. Then the door opened just enough for a nose and mouth to poke through.

“Yes?” came a wary female voice from the narrow crack in the door.

I tried to sound as cheerful as I could. “I live in the building, ma’am. I’m on council, and I’m in charge of the bylaws.”

“Oh, dear,” said the voice, and the door opened up to reveal a pale, tiny woman in a housecoat. She wore no make-up and her hair was tightly pulled back in a bun, with long, wiry strands shooting out everywhere as if the static around her head was overwhelming.

“Ma’am, there’s nothing to be worried about,” I assured her. “Don’t be concerned. Are you Mrs. Whipple?”

She nodded warily. “Yes…”

“Do you and, um, Mr. Whipple live here with your son?”

“Mr. Whipple does not live at this address. His address is now in Heaven with the angels.”

This startled me, and I was not sure how to respond. I collected myself and said, “Is it just you then, and your son?”

“Is this about Gray?” she whispered. “Oh dear, oh no – ”

I again tried to reassure her. “I told you not to worry. I don’t want you to be upset. I just want to speak with your son.”

“He’s not here.”

“Do you know where he is?”

“He’d down in the parkade playing his game.”

“What game is that?”

“The secret agent game. He’s hiding from his enemies.”

“Ma’am, can you tell your son that he shouldn’t be loitering about?”

“Oh, I tell him, I tell him,” she assured me.

“His behavior is an infraction of the bylaws, and he’s frightening some of the tenants,” I lied.

“Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear…” she kept repeating.

Before I could say anything more, tears began to spill out of this tiny woman’s eyes and roll down her cheeks. “Oh dear…I’m so sorry. I don’t want any trouble.”

I now felt guilty for making her cry. “Mrs. Whipple, please – “

“He was always a strange boy,” she interrupted through her tears. “When he was little he would always tell me that he was standing outside of himself and looking at his own thoughts. He said his thoughts told him to put his pajama top on backwards and forwards, backwards and forwards, over and over and over again before he’d go to bed. Oh, it worried my husband so, and it all gave him a heart attack and sent him to Heaven with the angels. I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I don’t want us to have to move. Please, please, please…”

She broke down sobbing and I knew the conversation was at an end.

“Don’t worry,” I assured her. “Ma’am, I’m sorry, too, for bothering you. Nothing’s going to happen, I promise.”

There is no trick to getting the upper hand on a secret agent if you’re the only one with the keys to the secret doors. I took the elevator back down to the basement and unlocked the door to the surveillance room, and within seconds of stepping inside I spotted Gray Whipple’s blurry image on one of the screens that showed the far wall of the parkade. I then went outside, hustled around the south side of the building, and quietly entered the parkade through the emergency door. Access to this door from the walkway also required a key that no secret agent could ever possess. My stealth maneuvers brought me immediately into the west end of the underground, where I was now only a few feet away from the elusive shadow-figure. He had his back to me and he was crouching behind the pillar next to the wall so no one from the adjacent driveway could see him. He was startled when I slammed the door and he immediately snapped his head around and sprang to his feet. He made a rather half-hearted attempt to run past me to the next pillar, but I stepped deftly in front of him and blocked his path. I was now face to face with the mysterious secret agent and I looked squarely into his eyes for the first time.

Secret agents may look handsome in the movies, but all I saw in front of me was an emaciated, sallow-faced schoolboy with sad eyes and a quirky, half-open mouth that gave him a frozen look of bewilderment. He had a pile of bed-hair slanting off in one direction that needed a good plastering down. But it was the expression in his eyes that almost knocked me over, and I was immediately reminded of someone I knew as a child and who I hadn’t thought about in years.

There was a park near where we lived, and in the summer there was this guy at the park who sold ice-cream to the kids. This guy was severely handicapped, and I remember how he was strapped into the seat of his little refrigerator cart with a big leather belt. He would drool and you couldn’t understand what he was saying, and the only part of his body that he could move were his fingertips. He would furiously tap-tap-tap his fingertips on the side of his cart, but no one ever understood what he meant, and no one paid any attention to him anyway. We would drop our money into his cup and take our ice-cream, and the poor guy was never cheated out of anything as far as I knew. I remember how my friend had never been to the park before, and how he reacted when he saw the ice-cream man for the first time. I remember the look in my friend’s eyes as he stared down upon the drooling man, paralyzed into silence, and tap-tap-tapping a message that no one ever heard.

The uncomprehending sadness that I saw in my friend’s eyes all those years ago was the same look that I now saw in Gray Whipple’s eyes, as if he had suddenly come upon me all strapped down and bent at the spine.

“Goodness,” I smiled. “Does the look of me shock you that much?”

“Nope,” he said. “I see you down here. You don’t see me, but I see you.”

Despite the nervous look in his eyes, I was surprised at how self-assured his voice was and how calmly his words were spoken.

“Ah, but you’re wrong there,” I smiled. “I do see you and that’s why I’m here.”

He did not respond, and I suspected he was waiting for me to give up and wander away.

“I had a little chat with your mother just now, and she told me a bit about you.”

“My parents gave up on me a long time ago. I love my mother, she doesn’t bother me.”

I kept my voice even and just quiet enough for him to hear. “Are you a real secret agent?” I asked.

“Maybe,” he replied, calmly.

“I used to have a little secret of my own, and you might be interested.”

I thought this might change the look in his eyes, but he didn’t waver and he didn’t answer.

I said, “When I was a kid, younger than you, I had this bizarre fear that I’d get run over by a car, or hit by lightening, or whatever. Ever had that fear?”

The boy didn’t miss a beat. “It’s not a fear,” he said calmly. “I look forward to it.”

I was not going to be deterred by such an obnoxious remark. I continued, “One night I put my pajama top on backwards by mistake, and I didn’t die the next day. To me, this was a sign of good luck. So every night I put the top on backwards before I put it on the right way. Then I got to thinking, well, ten signs of good luck were better than one, so I started to put the top on backwards ten times, so I would have ten times the protection from certain death the next day. It all made sense to me at the time.”

I waited for Gray Whipple to display some sense of neurotic kinship over this disclosure, but he seemed oddly unmoved.

I smiled, and then added, “Funny thing is, it seemed to work. I grew out of it.”

“Your parents should have had you locked up,” he said, impassive and unsmiling. “My mother tells everyone that story. She thinks somebody out there will give her the answer she wants.”

“I just gave you the answer, didn’t I?”

He looked away momentarily, then turned to me again. I knew there was little chance of any bonding with this kid. He said, “If you’re happy with yourself, that’s up to you.”

“I asked you if you were a real secret agent. Are you?”

“I like being a secret agent.”

“Do you like hiding from your enemies?”

“I hide from them, and then I get them in the end.”

“Am I your enemy?”

“Probably.”

“Do you have lots of enemies?”

“My share.”

“But no friends, I take it?”

“You don’t have any friends either. Don’t try to fool me, and don’t think you’re better than me. I know what you’re thinking.”

“You read my thoughts, do you?”

“I’m an observer of my own thoughts. Your thoughts are your own business, but yes, I can read them.”

“How do you observe your own thoughts? Is there another person inside of you?”

“Maybe I come down here to find out.”

“Have you found the other person yet?”

He considered this. “People think they can hide their thoughts,” he finally said. “They think their own thoughts are their sacred property. But the truth is, their thoughts are just as public as any walk through the park.”

“Can you read my thoughts?”

“You’d be surprised.”

“Would you be surprised to learn that I have plenty of friends, and you’re wrong?”

“You have social acquaintances, and that’s all you have.”

“You know this, do you?”

“When you read the obituaries every day, do you weep for every name you see?”

“I weep for my friends, I don’t weep for strangers. You’re spouting a trite philosophy, and it’s not even a proper comparison.”

“Well, I don’t think so.”

I was determined to make my point. “We all die,” I continued. “But if we’ve formed a bond in life with another person, call it love, call it friendship, call it whatever you want, then their death hits us harder than the death of a stranger. It’s a perfectly normal way to think, so don’t pat yourself on the back for being so clever.”

The secret agent was unimpressed. He said, “Just ask yourself, what’s gonna upset your so-called friends the most, your death or the loss of their property?”

“I hear you read all night and don’t sleep.”

“Yeah, sometimes.”

“Well, I read too, and I can tell you that you’ve just mangled a quote from Machiavelli. The proper quote deals with the loss of your father and the loss of your inheritance, and which one drives you to despair.”

“Same difference.”

I shook my head. “No, it is not the same. Everyone loses their parents, but not everyone loses their inheritance, so don’t go around making up trite comparisons to impress your friends.”

“You’re not my friend, and l don’t have any friends if that makes you feel any better.”

It occurred to me in that moment that I’d been drawn into an annoying conversation by a kid I had known for all of five minutes. I’d had enough, and it was time for the lecture. “My feelings don’t matter here,” I said firmly. “I’m a resident of the building, I’ve been elected to Council, and I’ve been appointed to enforce the bylaws. I didn’t come down here to engage in idle philosophies with a boy who lives in a fantasy world. You’re loitering down here. I’m here to tell you to stop it. Will you stop it, or do I go back upstairs to your mother?”

“I told you, my parents gave up on me years ago.”

“Your parents didn’t give up on you,” I shot back. I leaned closer to him to make sure he couldn’t slip away. “They were unable to handle you. Everyone gets to the point where they can’t handle something, and instead of running from it, which some people can’t do, they just leave it alone. They leave it alone in order to preserve their own sanity, and if your mother has left you alone then she has a dammed good reason for it.”

The kid seemed intrigued by this reference to his mother, and he didn’t move. I said, “Now I’m done with this discussion and I’m done with you, except for one thing…” I was now carefully slicing each word off my tongue. “One tiny, last little challenge. You say you can read my thoughts. You say my thoughts are as public as a walk in the park. Okay, then I challenge you to read those thoughts. I’m going to think of something and I defy you to guess what it is. I have a picture in my mind. I absolutely point-blank defy you to guess what that picture is. And when you make the wrong guess, as you most certainly will, I’m going to tell you again to take your secret agent act out of the parking lot and go observe your own thoughts somewhere else and quit making your mother cry herself to sleep. Do you understand me? I’m thinking of something. I have a picture. Tell me what I’m thinking.”

The boy looked at me as a hunting dog might look at a squirrel.

“You have a picture in your mind of three oranges on a red tablecloth,” he said.

We stared at each other for the longest time and Gray Whipple never changed expression. He still had the same look of sadness in his eyes that had struck me from the moment we began our strange discourse. Even now, when he knew that he had been correct and had guessed exactly what I had been thinking, his expression gave up no hint of satisfaction. If anything, his sad eyes seemed more deeply set into his skull and they looked sadder than ever before.

“That kid’s a mind reader,” I told my wife later that evening. “For the life of me, I don’t know how the hell he did it.”

“Did you tell him not to loiter in the parkade?”

“I’m not sure what I told him.”

“I keep telling you, you need a holiday.”

I had assumed that Gray Whipple would be back playing his secret agent game the next day. But I didn’t notice him in the underground after that, although he may have been more careful to hide behind the pillars and only dash out when I wasn’t around. My wife hadn’t noticed him either, but I knew that all the remonstrations in the world from the bylaw officer could never intimidate this kid, or deter him from whatever secret mission his private demons had forced him to undertake. Still, I didn’t see any more of him and I decided to leave well enough alone, which was a bit of a minor victory as far as I was concerned.

About a month after our little chat in the underground, I was driving by the high school and I spotted Gray Whipple on the sidewalk. There was a group of kids marching ahead of him who were all involved in some sort of animated, frenzied discussion. There was about ten of them pressed together in a tight pack. They were flailing their arms and laughing and shouting furiously over each other as they hurried along, spilling onto the roadway, oblivious to traffic and anything else that was not a part of their exclusive little world. Gray was not a part of their world either, but he was following close enough behind to give an onlooker the impression that he was a buddy trying to catch up. A stranger would assume that he, too, would soon become one of the laughing kids without ever suspecting that he never intended to take those last few steps. He was wearing a black hoodie-type jacket and he had the hood pulled tight over his head as if he did not want anyone to recognize him. I slowed my car and I watched him walk along, hunched over with his hands in his pockets and his head down, staring blankly at the sidewalk, always keeping a few deliberate steps back from the raucous mob in front of him. A part of me wanted to call out to him and ask him to read my thoughts, but I thought the better of it and kept driving.

Not long after that, I ran into Joe the building manager.

“You hear about that kid?” he said casually.

“You mean Gray Whipple?”

“Yeah, the secret agent kid. Police came around here, told me the kid made his way over to Highway 17 and then walked right into traffic. Tragic thing.”

At that moment, I had a vision of poor Mrs. Whipple in her hallway and all that static hair. “Is his mother okay?”

“She doesn’t come out,” Joe said. “Nothing much she can do.”

When I told my wife the news, she was saddened but not surprised. There was a pause as we thought about the most appropriate thing we should say to each other. Then she said, “He wouldn’t have had a happy moment, ever.”

“You’re a D.H. Lawrence scholar, aren’t you?”

She seemed baffled by my question. “Well, give me your quote and we’ll see.”

“Do you think it’s best to go out of a life where you have to ride a rocking horse to find a winner?”

“You could get a PhD in Lawrence and you still wouldn’t know what it all means. The highbrows say they know, but they’re full of it. It’s cynical, and that’s all they know.”

I thought about this. I said, “We don’t really know if both kids ever found what they were looking for, the kid on the horse and the kid in the parkade.”

“Maybe they did find what they were looking for, and they couldn’t deal with it.”

I thought abut this, too. “You know how Paul and Peggy fuss about that cat of theirs?”

“That cat has nothing to do with D.H. Lawrence, and you desperately need a holiday.”

“Humor me. I’m talking about our best friends who we’ve known for over thirty years.”

My wife nodded. “Yes, yes, they’re our best friends.”

“You talk about the highbrows being cynical, but how cynical are you?”

“When you stop speaking in riddles I might answer you.”

I hesitated, and then popped the question. “When you die on the same day as their beloved pet, who garners the most grief – you or the cat?”

My wife was never slow to miss the point, and she did not hesitate. “The cat, and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

I lay awake that night thinking about Gray Whipple. I don’t believe he ever did find what he was looking for before he decided to step out into traffic and put an end to his own thoughts. If he was indeed capable of observing those thoughts, all he would ever find was more sadness – exactly like the kid on the rocking horse.

We are all born into sadness, burdened by challenges known only to God, and tied together by secrets so deep that even a secret agent can’t find them.

BIO

Robert Collings is a retired lawyer living and writing in Pitt Meadows, B.C. The Secret Agent is Robert’s second appearance in Writing Disorder. The Tears of the Gardener is archived in the Spring 2021 edition. Robert has also published online in Euonia Review (eunoiareview.wordpress.com), Scars Publications (scars.tv), and Mobius magazine (mobiusmagazine.com). His stories appear in print in cc&d magazine and Conceit magazine, and all are found in Robert’s collection called Life in the First Person.

Robert has not won many awards in his lifetime, although he’s proud of a “Participation Certificate” he received for coming dead last in the 50-yard dash in the third grade.