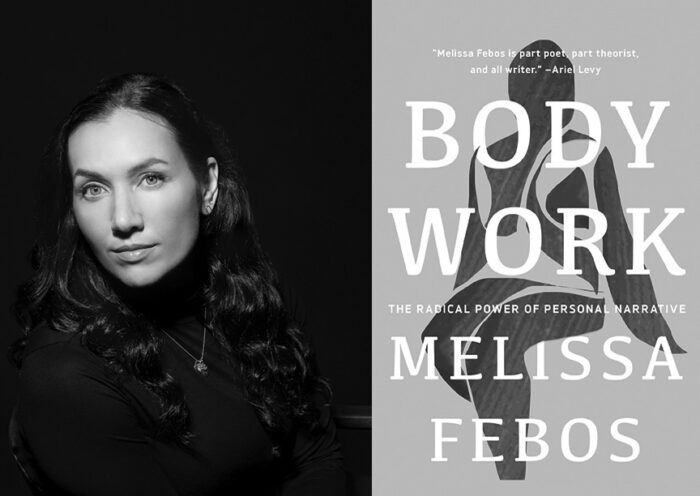

Writing as Recovery: Melissa Febos’ Body Work

By Kate Brandt

In the January 10, 2022 issue of the New Yorker, an article by Parul Seghal appeared called “The Key to Me,” and advertised as The case against the trauma plot. I dropped what I was doing and read it instantly. As a writer who draws mainly upon the struggles of my own life for material (my ex-husband joked that I should call my unpublished novel “The Things That Hurt Me”), I wanted to know precisely what I was being accused of.

As I read, my fears were confirmed. Seghal laments the proliferation of what she calls “the trauma plot” in contemporary storytelling, listing many examples and complaining that their creators cannot “bring characters to life without portentous flashbacks to formative torments….the trauma plot,” writes Seghal, “flattens, distorts, reduces character to symptom.”

What a magnificent counterargument can be found in the essays that make up Melissa Febos’ new craft book, Body Work. Although Febos’ essays focus on memoir rather than fiction, they very much take up the argument. Each piece focusses on a different aspect of memoir writing, but Febos’ embrace of trauma as material for writing would make Segal shudder—indeed, Seghal mentions Febos’ words on trauma as an example of how oppressive “trauma narratives” have become. The elegance and depth of Febos’ writing in this collection are the best comeback.

In “In Defense of Navel-Gazing,” Febos’ justification for writing the self is three-pointed. One of these points is political. She writes:

That these topics of the body, the emotional interior, the domestic, the sexual, the relational are all undervalued in intellectual literary terms, and are all associated with the female spheres of being, is not a coincidence. This bias against personal writing is often a sexist mechanism.

Citing works like Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Diary of a Young Girl, and Night, she points out that “Social justice has always depended upon the testimonies of the oppressed.”

A second point of her defense: Personal writing is art. Just because we write about ourselves, this “does not excuse you from the extravagantly hard work of making good art, which is to say art that succeeds by its own terms.”

Her third point: It heals. Febos cites a study done by James W. Pennebaker in the 1980s, in which people were instructed to write about a past trauma. The results:

Monitoring over the subsequent year revealed that those participants made significantly fewer visits to physicians. Pennebaker’s research has since been replicated numerous times, and his results supported. Expressive writing about trauma strengthens the immune system, decreases obsessive thinking, and contributes to the overall health of the writers.

Later essays in Body Work focus on writing sex scenes, writing about others in memoir, and writing as recovery. In the last essay, Return, Febos dives deeply into the connections between healing, art, and the divine. This is where Febos leans most on trauma and is also the point at which I was most drawn in. Rather than expressing embarrassment about the confessional nature of memoir writing, Febos celebrates it.

In Return, Febos recalls a longing she felt, even as a child, for a certain transcendence. This longing found an outlet in writing, a need and obsession that never left her. As a child, Febos tell us, she wrote with “religious enthusiasm.”

As a mature writer, writing sometimes afforded her a chance at that longed for transcendent state. Febos describes herself at a residency, writing the story of an obsessive relationship in her life. As she wrote, in

a kind of trance, characterized by total self-forgetting…inside an intelligence…loyal only to the work to which it is applied…I had the lucid and entirely certain realization that there was only one correct ending to my story: my narrator would leave her lover.

In the act of writing, she had unearthed truths about why she was in the relationship that she had hidden even from herself, and which she subsequently acted on—life follows art. Febos here uses the word “recovery” in both senses—a healing from illness, but also retrieval of some aspect of the self that had been lost to the writer—and shows that these two meanings are intimately connected.

My own novel, coming out next year, is autobiographical. If I had to say what it was “about,” I would list these themes: passion, the Buddhist concept of emptiness, illusion, and depression.

Depression is difficult to capture on the page. So heavy, so paralyzing, so…wordless. While writing countless drafts, that was probably where I got stuck the most—how to show what that kind of despair is like.

I spent roughly thirty years of my life in and out of therapy with a diagnosis of major depression. A fact that, as one friend put it, was ridiculous. It was. I was white, middle class, heterosexual, educated, healthy, gainfully employed, and at that age, good-looking. I had no right to feel the way I did.

But there it was—chronic insomnia; daily crying fits, drinking myself to numbness nearly every night.

How many times during my depression was I told by friends and family to “get over it?” When depressed, that is exactly the problem. Intellectually, I knew: yes, I should get over this. But I didn’t.

In Return, Febos mentions an attitude of toughness she took to her own sexual trauma at a certain point in her life. “Embedded in that choice,” she writes, “was my abiding belief in the fantasy of toughness.” This attitude covered a deeper sense of shame she felt. In her first attempt at nonfiction, she tells us, she wrote about the experience of being a sexual submissive for pay. She was not ashamed of what she had done, but rather “I was more ashamed of my unknowing than of my actions…for me, at twenty-five, a lack of self-knowledge was a cause for shame.”

I recognized both states of mind. When I began to write, I, too, hoped writing could be a tool that would help me resolve unanswered questions and the shame I felt about my depression. My friends were right of course—I had plenty of privilege, a lot “going for me.” How to explain myself? What was wrong with me, after all?

I also had ambivalence about writing my own story. I had, at that point, been studying Buddhism for a few years, and my teacher made a point of urging his students not to get mired in our own self-pity. A key tenet of Buddhism is the idea of “no-self,”—that we manufacture an idea of self through the combination of sensations that coalesce in our brains. If we are to cultivate awareness of this truth, focusing on a narrative we create about ourselves would be counterproductive. This teacher ridiculed students who wanted to pour their hearts out to him. I remember once trying to speak to him about things that troubled me. He smiled gently. “Soap opera,” he said.

I wrote about myself anyway. I had to. Like Febos, I wrote to free myself from the shame of own lack of self-knowledge. In the long process of trying to know myself more deeply through writing, I found that writing changed me.

Story has its own demands. There must be verisimilitude. There must be a shape. In the struggle to bring these elements to my personal story, an interesting alchemical process took place. Slowly, draft after draft after draft, I began to get some distance from my pain. The hold that my story had on me, especially the despairing, self-pitying part, began to loosen. I came to see the “things that hurt me,” as my ex so mockingly put it, were actually, in a sense, accidents. It wasn’t personal.

In Return, Febos writes that “memoirs begin as conversations with the self…Our first confessions must be to this internal witness.” Through this process, both textual and spiritual, we begin to see ourselves clearly, and, more importantly, forgive ourselves. When she writes, Febos tells us, she is two selves—the one who has experienced the past, and the one who observes, processes, and sees through what she thought was there. “By my own higher power, by the self that is capable of holding the most pitiful part of her past and loving her clean” Febos is able to clearly see a former self, and have compassion.

I had a similar experience writing my own life. At a certain point, I realized that while much of what my Buddhist teacher had instilled in me was valuable, contempt for myself and my own story, my own version of myself, was not. It came to me that if Buddhism was a religion based on compassion, there was no reason not to have compassion for myself as well, and that this compassion, paradoxically, made me more emotionally available to others. What I’m trying to say, I suppose, is that in Body Work, I believe Febos unearths valuable truths.

I write, but my main occupation is teaching adult literacy. I’ve done this work since 1990, working with adults who dropped out of high school for various reasons such as pregnancy or the need to care for a family member, as well as immigrants who received various levels of education in their own countries.

Few groups are more in need of writing their stories. Most of my students have suffered, and continue to suffer, multiple traumatic experiences—the traumas of racism and/or immigration; the shame of being less well-educated; the ongoing hardship and humiliation of poverty. Teaching adults has shown me that, regardless of literacy level, the wish to be heard is universal. When I ask my students to write; when I repeat to them the adage that my own writing teacher shared with me—tell the story only you can tell—there is often a moment of hushed surprise. Me? A story? And then, permission granted, they begin.

“The final phase of trauma recovery,” writes Febos in Return, is often described as grounded in a reconnection and restored engagement with social life.” This reconnection with the community is another spiritual aspect of confession as Febos conceives of it in the essay, and it is something my students understand instinctively. The stories can be heartbreaking—multiple foster homes, addiction, losing one’s own children. When one student reads, the rest of us listen respectfully and for as long as it takes for the storyteller to finish. At other times in class—when reviewing comma use, or the parts of a cell—I may be divided from my students by our different backgrounds, but when we read our personal narratives, we are always a community as sacred as church.

Seghal complains that the “trauma plot,” as she calls it, “reduces character…can make us myopic to the suffering of others…disregards what we know.” Febos is more generous.

“Listen to me,” she writes. “It is not gauche to write about trauma…bring me your books about girlhood, about queer families and sex workers, your trans bildungsromans. I will read them all.”

Febos dedicated her book to her students, but this book will touch many of us—all of us who have questioned our right to speak—who have not thought ourselves worthy of being heard. It’s one thing to be censored, spoken over, silenced by others—quite another to do it to yourself. In Body Work, Febos has freed us from that self-censure, and I am grateful.

BIO

Kate Brandt’s work has appeared in various publications, including Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Talking Writing, Literary Mama and Redivider. Her novel Hope for the Worst will be published by Vine Leaves Press in 2023. She works as an adult literacy instructor in New York City.