MY LIFE BY DISNEY

by Dana Roeser

At twilight

when I was gathering

newly sprouted arugula

in the backyard garden, a cardinal

sang to me

from the high limb of

an ancient elm. It was a sweet

song

that I tried

to answer. I apologized again

for Alice killing the robin

because the more I think of it

the more I think she did

do in Laura.

A day after the murder

I pulled up in my dirt-streaked Toyota

sobbing so hard

I soaked a box of Kleenex.

I could hardly get up the steps.

Alice was inconvenienced, always

having to use the back door. Was she inconvenienced

by my caring about the robin?

* * *

I will not, I cannot,

look in the nest

high up under the eave

of my house.

The babes in the woods

clinging to each other

in the cushiony bed—frozen with their mouths open—

their rubbery beaks—

Or were they still perfect eggs—unhatched—

also frozen—

b/c the mother left

against her will?

I’ll never look at Alice the same. And truly I

don’t know she was the perpetrator.

The one time that I left her out

when I pulled away.

I knew I’d be back in a couple hours.

I knew the weather was sunny

and hospitable.

Alice stared at me

from the end of the driveway

because she likes to go in when I’m out.

But I was embarrassed

being already seven minutes

late for Sarah, and I didn’t want

to open my car door,

disrupt the bird.

Immaturity is my humility—but that’s for another poem—or no poem.

(Ask the cardinal.)

The bird calls are a relay, a transference.

They know each other

and they all have witnessed it.

The father, somewhere, witnessed.

That is the only explanation for the disappearance of

the dogged mother.

She sat on that nest, breast puffed, eyes bulging

and inscrutable,

her tail jutting out like a stick

through cold rain—she was under the eave, I watched her from

little arched windows at

the top of the front door. It was ridiculous,

the weather.

We had more than one night

at freezing. (I was busy then covering the

baby greens with bed clothes.)

The neighbor cats

were not clued in, had no

territorial vendetta, though they, especially lithe Horace, may

have been called in as accomplices.

Tonight. I had come from a twelve-step meeting

where people were kind.

I went to one at noon too—I said just who did I think I was?

Mother-goose? A bird-whisperer? Yet,

Beach, at Clay Knob Stable today, was also kind,

soft, grabbing for apple pieces with

his velvety, oversized lips—and disappointed,

I’m sure, that we didn’t get to do our after-

ride ritual (Christy turned him out

for me) because I had to run

to the car before 4 p.m. to do a financial thing

on the phone, the stock market

had supposedly rallied.

My ex-husband told me

today was a good day.

I have no income to speak of, as I am old.

I am spending down the funds that came to me

in the divorce. I am almost five years

older than my former husband.

He still has a job.

Income from the part-time job I did have this semester,

according to my accountant,

actually cost

me money.

Do the math.

Weep.

How in the hell

did I mislay this man

and my family?

Why can’t I visualize

my Canadian boyfriend

when he is not here?

My dear Canadian boyfriend who actually said on

Messenger this week:

If we break up (or words

to that effect), if I have to get a girlfriend

(online/yoga class/

coffee shop, etc.)

because I can’t wait any longer

for us to be together,

“I will always interact with you.”

Jesus Christ on a bright purple crutch!!!!

And then on my way home from my circuitous

“self-care” travels today,

I realized our relationship

was another victim

of my “magical thinking.” As durable

as Sleeping Beauty

or Snow White—their chirping, carefully-colored birds

and chipmunks—

bursting into song . . .

while Laura is

carefully extracting worms

from my little as-yet-untilled strip garden

between house

and driveway

under the nest—

the cat’s

going to get her

with lightning speed,

with sharp claws.

O HOLY WEEK, O HOLY SATURDAY

Black Saturday Jesus is in the tomb

germinating and the people

across the street are rocking out

to some kind of grinding repetitive

hip hop, interspersed with Bollywood.

We are college students

We are going to be having a loud

party this afternoon

and we deserve to enjoy college. So Jesus

hung in his cocoon while

I burned a fire, opened all the windows,

felt suicidal and went through

mountains of random bills catalogs manuscripts

and papers and ultimately

raked through cat litter, took it out with garbage,

recycling, and compost

all to the grinding neighborhood beat. Kept trying

to figure out what they could

do to it. Not sex. Not work. Maybe shouting

at each other at a party, clambering over

each other, dominating

on their huge wooden oversized chair

in the back yard or in the ever-repeating

hacky sack or foosball game.

What is really the use of trying

to win at divorce counseling

when you flunked marriage counseling

and your ex-husband has a personality

disorder? Patti my beautiful, stoic

Buddhist AA

sponsor tried to say.

When you already lost

spectacularly.

What is your expectation, I believe

she said. Also, maybe implicitly, well

NVM implicitly. Let’s just say

Patti knows me, has known me. I’m surprised

she speaks to me.

Jesus was still hatching while this evening I rolled

my cart through Fresh Thyme. Some appearing-

families, endless sturdy children rolling

in and out of carts;

the stringy-haired

tender-looking Goth woman in

the soup aisle, the very thin wan blond

woman with whom I conferred over the

sushi case. Only California Roll

remained. She put hers back,

and, later,

I did mine. Bland tonight

even worse tomorrow and what was I doing

eating all that white rice. Couple other

random people. Somebody by the Medjool organic

dates, I think. Maybe a couple near the

remains of the broccoli or bok choy. Produce

waning. We were all convivial.

We were all flunking Easter.

At every turn, the handle of my cart

was shocking me.

After the checker saw the absurdly

expensive “natural,” with-the-shiny-foil

packaging, Sierra-something,

couture cat food I bought

and I told her how much better

my cats’ coats were, she and I

went over her mini-labradoodle

stud’s diet and coat

supplement. Apparently

his coat is bedraggled. He’s still picked

up by the breeder twice a month

to do his thing, but it appears that

it’s wearing him out—all

those different women—or that was

my guess. I told her I wanted

a dog, which made us both

happy, me b/c it would

get me out of the man thing.

The loneliness thing.

All this while a line of people

formed behind me and random

groceries were plowing

forward on the belt.

Driving home

I thought about how sad Beach had seemed

at the barn yesterday, grounded

in his stall with his hurt foot and the dear

young person, who must be

home-schooled, far too innocent at age

seventeen to be attending

any public high school even

in rural Indiana.

Her fresh face in my face

asking me all sorts of questions about

Beach, about patient, shark-faced Indy whom

I’d ridden that day instead of Beach,

about posting the trot,

and so on. And today

at Fresh Thyme

the other young person maybe

the same age or a bit older

going on about the mini-labradoodle

set up. They sort of lease the dog, foster

him, whatever.

In all seriousness, I think these

dear earnest young people are what

Jesus is thinking about there

in the dark. They’re inheriting rampant

porn, a frying earth, a parent-

and grandparent-killing pandemic. Oh,

and a brutal war and genocide

on television. & that other thing.

My raspberries at some point must’ve

gotten loose, were rolling all over the grocery

bag apparently, because several

dropped into my yard when I got home

and I just popped them all

in my mouth. All that abundance. All that

freshness on the young

people’s faces.

Jesus, think hard. Meditate hard.

As previously stated, I don’t know how

Patti can stand me, and come to

think of it, I’m not sure she can. We talked

about meditation. A woman she reads

who writes about Zen and the twelve steps.

Irish formerly-Catholic Patti said “I hate Easter”

and I must say it was something of a relief.

I’d neglected to say I’d wanted

to write to my hot convert friend

up in Toledo

and say Happy Easter,

that I missed the big bonfire at my former church

in which we threw

our palms from the week before;

our little candles lit, blown out,

and re-lit in the dark sanctuary. The Litany of

the Saints, so beautiful, to which I’d sobbed every year—

including three years ago—not two hours

before, in our living room, exhausted—

I’d been to a student event

with my husband before the service—

and the Vigil had lasted three and a half

hours—when my husband told me he was

leaving me.

The week after that I went back

to Mass, not knowing where else

to take my outsized pain—it was packed

and a woman next to me gave me

her handkerchief

as my sobbing was getting messy—

and I was convinced it was a message

from my dead father who always gave

me a hankie and whose clean, folded handkerchiefs

looked just like hers.

I could hardly get out of the church after

Mass or through the ensuing

days in which my husband vaguely confessed

about two other women and precisely

set about organizing his move which happened

ten days later.

How many times had I stood

in that parking lot before that fire

with my husband and sometimes one

or the other, or both, of our daughters?

And then gone

in to stand in the dark sanctuary waiting

for our little white candles

in the paper cones to be lit hand to

hand from the priest’s

Pascal candle. Staying standing

for the long, long reading

of Genesis where

God divided the light

from the darkness and Exodus, the

Lord in the pillar of fire

and cloud. Oh how I wish I were there now.

I heard we are having

yet another hard frost tonight

—though it is April—

and again I congratulate myself

for not planting anything yet.

I’m sure it is beautiful there at the garden

under the dark, pink full moon.

Holy Mary, mother of God, pray for us.

Saint Michael, pray for us.

Holy Angels of God . . . .

The frost drops tonight

like stars.

Perfect hairy red raspberries tumbling

out of the back door of my car

and into the yard.

HAPPY DAYS

Belle hiding in the narrow brush jump

covered with red faux-brick paper. (Note to both horse and rider:

the thing will not give.)

Her fluffy head

and fat tail coming out of the open top. Frustrated Cohen the

black pit bull cross

hanging around her licking her face.

Christy says Let me get a rope for the dog

so I can rescue the cat

and Roxy can jump the brush jump.

I’m trotting around on Beach. I had to do energy work—

my guestimate of Reiki—

on the horse before I went out there. Seriously.

I didn’t know that that was what I was doing.

But he lowered his head and let his eyelashes drop

when I stroked

the bone behind his right ear.

Also looked at me dreamily

when I kissed him square on the face.

Riders don’t always realize that horses

need reassurance. The day before’s lesson, C. admitted,

“went south.” We were scraping mud

off Beach from either side.

She thought 13-year-old Suzette could handle him,

but instead he veered right

and broke into a canter down

the rail—

maybe she poked him with her heel—

Suzettte ended up coming off INTO the wall of the indoor

breaking off a tooth—and fracturing her jaw.

Still she had the presence of mind,

Christy said, to ask for someone to look for

her tooth. (Which I did not know

until today was even

a “thing.” Those who watch

hockey know about it?)

I’m sure the mom was not pleased, but

the liability waiver

—which refers to the “inherent risks of equine activities”

and “death”—is in huge block letters on

the tack room door.

And everybody signs a copy.

My job today was to calm Beach down

enough to get him to go over the small jumps

without running out. (Or, God forbid,

into one of the hayfields stretching in

every direction.)

Lily, another beginner, had helped him to realize

that running out might be an attractive option.

The cat hiding in the brush jump, with the dog sniffing her face

reminded me of how John, about age 12, used to hold

Douglas, age 10, down on the floor and I would slap him.

Then when Mother appeared, John and I would lie.

I am getting ready to confront my ex-husband

in divorce counseling, to let him know

how much he hurt me. Is that not the most laughable

thing you ever heard? Like a person who

pursued two

people while holding my hand

in “marriage therapy,” as he called it,

would suddenly

be capable of compassion?

Ha ha ha.

The cat’s head rotating around above the box reminded

me of the woman’s head in Happy Days

the Beckett play my boyfriend lent me.

Honestly, the grief over our uncertain future

is tormenting each of us

in different ways. He can’t get across the Canadian/U.S. border

and I am a basket case about going up there.

My love bleeds and I go very blank. If I’m going to

have excision surgery I need to prepare for it.

I need energy work. On myself. Courage to

get dipped in acid

again.

I DO NOT visualize myself as Winnie in

Happy Days, the tiny circuit of toothbrush,

toothpaste, and comb—

buried to her waist in an earthen mound

beneath a “trompe-l’oeil backcloth” of

“unbroken plain and sky.” A black bag and

parasol beside her. When will “Willie,”

lying asleep

somewhere behind her, speak?

Brush and comb

the hair if it has not

been done or trim the nails

if they are in need of trimming. . . .

This is going to be another happy day!

REVOLVING DOOR OF SPRING: CHECK ON ME

Trina T. has gone back out.

It was all over WLFI.

Two OWIs in twenty-four hours.

First she got hung up on

a snow drift, drunk, then motored off

from the officer

who tried to help her. Then she

had an accident. “You should

have seen her mug shot,” Emily said,

“and people were

saying things like ‘Lafayette’s finest’

in the comment

section. Brandi and I had to

defend her.”

March 11th, apparently,

is the day my father will be released from

the hospital. On his 93rd

birthday, his blood pressure was 69

over 40.

“I always think

March 11th is the day we start

to ride outside,” Christy says.

“We could probably ride in the outdoor

today but we wouldn’t

be able to get there. All the snow is

melting—the ground

is soaked.” March 11th is three days from

today. No one knows if Trina has

been bailed out.

Her husband had just gotten

out of prison which “could

have been a factor.”

That train accident

was by my rather obvious

deduction a suicide. The train

was coming from the west

and Rachel just rolled

her truck slowly onto the track.

Three-column obituary. An engineer

who traveled the world, rode

and showed a horse

named Orion, loved guinea pigs, pottery

(which she made), sunflowers.

In other words, who lived eighty

lives to my one. Christy

and Josie knew her. I heard about it

at the barn when I was

having my lesson. Walking and trotting,

always getting yelled at,

always waiting for the chance

to jump (when I was young, it was “hunt”).

A hanger-on at the barn—with ten-year-old

cohorts, college girl

stable helpers. “She, the witness, observed

and heard the train

coming from the west

and saw the pickup truck

slowly edge up onto the tracks,” said the

Chief Deputy.

When Doug heard

about Dad, via my voice mail, yesterday,

it took eight hours for

him to get back to me. He was

talking really slow. I wondered

how much he’d been

drinking. I could tell

he didn’t feel up to calling Thea and sorting

out the visiting rotation.

When they

told me Tammy died, I had

to look up her obituary picture

to remember who she was. Emily,

recently relapsed and on the run

from CPS (having been caught driving drunk

with her child), was the one

who found her. When you endanger

children as much as she has, Child

Protection Services becomes CPS. Emily had tried

to call Tammy to check on her

but she didn’t pick up. When

Emily went over to check on her, she

found her naked on the

bed, fresh—or not—from the

shower. Emily flashed back to her mother’s

suicide by alcohol overdose,

replete with note, on her ninth birthday,

and then tried to kill herself two and

a half weeks later. It was Tammy’s sister

who called to check

and upon hearing Emily’s garbled voice

called 911. She had been very, very

thorough in her overdose, though I can’t

remember right now what

combination of drugs and alcohol she told

me she used.

Arlene at the nursing home

was perfectly cheerful about

my father last night, said she

only wished they’d caught it sooner

so he could have avoided going

to the hospital.

He sounds

like he is trying

to speak from a deep

well. Thea said on the phone

that when she arrived she found

him “unresponsive,” deploying

a medical default/buzz word. I knew

it would be okay, though, because

the night nurse “Jackie” last night

on the phone said she was right

outside his door, had just checked on him, and

that he was “adorable.”

A man in the my

home meeting about

whom I’ve been nursing

some kind of an obsession asked me

for my phone number and I nearly

died. I kept thinking, Is this a date? I gave

him my number and my last

name and he gave me his. I know what it was

really for. I know we had

more important things to do

in that room than

have a Valentine’s dance. I think about him,

how raw and in pain he seemed a

month or two ago, how I was worried

he’d go back out

(but he didn’t and that was all

that mattered).

When Andy refused

to watch Lola, and Mia was paranoid,

I told her to ask

the reason. She ended up

sobbing to him on the phone. Then

someone she knew from Lola’s school

saw Mia in Target in the hour

before the meeting and offered to take her so Mia

could have some peace.

Andy said it was just work that

was bothering him. Mia’s friend

texted a photo of Lola at Tractor Supply—

or was it Rural King?

I didn’t ask the man why he wanted

my number. I did not want

to end up sobbing.

Doug,

it’s Daylight Savings

Time, drag yourself up out of that

hole you’re in. Dad is not dead.

Let’s work on his obituary while there’s

still time. I’ll tell you

when it’s otherwise. Slim, in your

gold shoes, carry on,

keep deploying your charm. Mia,

tell the truth to Andy. Emily, one day

at a time, keep coming back. I’ll call you,

Doug, and tell you when to

enter the hole for good. Meanwhile, pick up

your phone once every

thousand years. Let me check on you.

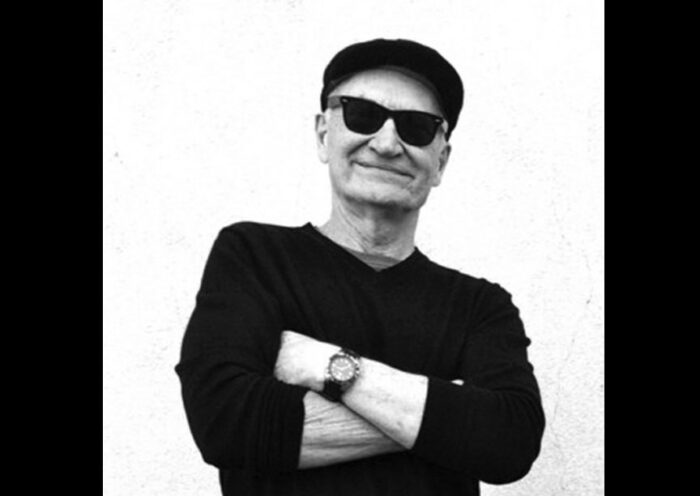

BIO

Dana Roeser’s fourth book, All Transparent Things Need Thundershirts, won the Wilder Prize at Two Sylvias Press and was published in September 2019. Her previous books won the Juniper Prize and the Samuel French Morse Prize (twice). She was a recipient of the GLCA New Writers Award, an NEA Fellowship, a Pushcart Prize, and several other awards and residencies. Recent work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in Poem-a-Day, The Glacier, North American Review, DIAGRAM, Pleiades, Guesthouse, Barrow Street, Laurel Review, and others. For more information, please see www.danaroeser.com.